Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | One of the Main Organizers of the Holocaust |

| Birth Day | March 19, 1906 |

| Birth Place | Solingen, Rhine Province, Germany, German |

| Age | 114 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 1 June 1962(1962-06-01) (aged 56)\nRamla, Israel |

| Birth Sign | Aries |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Other names | Ricardo Klement |

| Occupation | SS-Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel) |

| Employer | RSHA |

| Organization | Schutzstaffel |

| Political party | National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) |

| Criminal charge | War crimes, genocide, crimes against humanity |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Spouse(s) | Veronika Liebl (m. 1935) |

| Children | Klaus Eichmann (born 1936 in Berlin) Horst Adolf Eichmann (born 1940 in Vienna) Dieter Helmut Eichmann (born 1942 in Prague) Ricardo Francisco Eichmann (born 1955 in Buenos Aires) |

| Parent(s) | Adolf Karl Eichmann Maria (née Schefferling) |

| Awards | Iron Cross, Second Class War Merit Cross 1st Class with swords War Merit Cross 2nd Class with swords |

Net worth: $1.1 Million (2024)

Adolf Eichmann, known as one of the main organizers of the Holocaust in German history, is reported to have a estimated net worth of $1.1 million in the year 2024. Eichmann, a high-ranking Nazi officer, played a central role in coordinating and facilitating the mass murder of millions of innocent lives during World War II. Despite his horrific actions, Eichmann managed to escape capture for many years before finally being brought to justice in 1960. His trial served as a crucial milestone in exposing the atrocities committed during the Holocaust, shedding light on the extent of Nazi war crimes.

Famous Quotes:

Long live Germany. Long live Argentina. Long live Austria. These are the three countries with which I have been most connected and which I will not forget. I greet my wife, my family and my friends. I am ready. We'll meet again soon, as is the fate of all men. I die believing in God.

Biography/Timeline

Otto Adolf Eichmann, the eldest of five children, was born in 1906 to a Calvinist Protestant family in Solingen, Germany. His parents were Adolf Karl Eichmann, a bookkeeper, and Maria (née Schefferling), a housewife. The elder Adolf moved to Linz, Austria in 1913 to take a position as commercial manager for the Linz Tramway and Electrical Company, and the rest of the family followed a year later. After the death of Maria in 1916, Eichmann's father married Maria Zawrzel, a devout Protestant with two sons.

After an unremarkable school career, Eichmann briefly worked for his father's mining company in Austria, where the family had moved in 1914. He worked as a travelling oil salesman beginning in 1927, and joined both the Nazi Party and the SS in 1932. He returned to Germany in 1933, where he joined the Sicherheitsdienst (SD; Security Service); there he was appointed head of the department responsible for Jewish affairs—especially emigration, which the Nazis encouraged through violence and economic pressure. After the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, Eichmann and his staff arranged for Jews to be concentrated in ghettos in major cities with the expectation that they would be transported either farther east or overseas. He also drew up plans for a Jewish reservation, first at Nisko in southeast Poland and later in Madagascar, but neither of these plans was ever carried out.

Eichmann attended the Kaiser Franz Joseph Staatsoberrealschule (state secondary school) in Linz, the same high school Adolf Hitler had attended some 17 years before. He played the violin and participated in Sports and clubs, including a Wandervogel woodcraft and scouting group that included some older boys who were members of various right-wing militias. His poor school performance resulted in his father withdrawing him from the Realschule and enrolling him in the Höhere Bundeslehranstalt für Elektrotechnik, Maschinenbau und Hochbau vocational college. He left without attaining a degree and joined his father's new enterprise, the Untersberg Mining Company, where he worked for several months. From 1925 to 1927 he worked as a sales clerk for the Oberösterreichische Elektrobau AG radio company. Next, between 1927 and early 1933, Eichmann worked in Upper Austria and Salzburg as district agent for the Vacuum Oil Company AG.

On the advice of family friend and local Schutzstaffel (SS; protection squadron) leader Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Eichmann joined the Austrian branch of the NSDAP on 1 April 1932, member number 889,895. His membership in the SS was confirmed seven months later (SS member number 45,326). His regiment was SS-Standarte 37, responsible for guarding the party headquarters in Linz and protecting party speakers at rallies, which would often become violent. Eichmann pursued party activities in Linz on weekends while continuing in his position at Vacuum Oil in Salzburg.

Nazi Germany used violence and economic pressure to encourage Jews to leave Germany of their own volition; around 250,000 of the country's 437,000 Jews emigrated between 1933 and 1939. Eichmann travelled to British Mandatory Palestine with his superior Herbert Hagen in 1937 to assess the possibility of Germany's Jews voluntarily emigrating to that country, disembarking with forged press credentials at Haifa, whence they travelled to Cairo in Egypt. There they met Feival Polkes, an agent of the Haganah, with whom they were unable to strike a deal. Polkes suggested that more Jews should be allowed to leave under the terms of the Haavara Agreement, but Hagen refused, surmising that a strong Jewish presence in Palestine might lead to their founding an independent state, which would run contrary to Reich policy. Eichmann and Hagen attempted to return to Palestine a few days later, but were denied entry after the British authorities refused them the required visas. They prepared a report on their visit, which was published in 1982.

By 1934, Eichmann requested transfer to the Sicherheitsdienst (SD; Security Service) of the SS, to escape the "monotony" of military training and Service at Dachau. Eichmann was accepted into the SD and assigned to the sub-office on Freemasons, organising seized ritual objects for a proposed museum. After about six months, Eichmann was invited by Leopold von Mildenstein to join his Jewish Department, Section II/112 of the SD, at its Berlin headquarters. Eichmann's transfer was granted in November 1934. He later came to consider this as his big break. He was assigned to study and prepare reports on the Zionist movement and various Jewish organisations. He even learned a smattering of Hebrew and Yiddish, gaining a reputation as a specialist in Zionist and Jewish matters. On 21 March 1935 Eichmann married Veronika (Vera) Liebl (1909–93). The couple had four sons: Klaus (b. 1936 in Berlin), Horst Adolf (b. 1940 in Vienna), Dieter Helmut (b. 1942 in Prague) and Ricardo Francisco (b. 1955 in Buenos Aires). Eichmann was promoted to SS-Hauptscharführer (head squad leader) in 1936 and was commissioned as an SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) the following year.

Lothar Hermann was also instrumental in exposing Eichmann's identity; he was a half-Jewish German who had emigrated to Argentina in 1938. His daughter Sylvia began dating a man named Klaus Eichmann in 1956 who boasted about his father's Nazi exploits, and Hermann alerted Fritz Bauer, prosecutor-general of the state of Hesse in West Germany. He then sent his daughter on a fact-finding mission; she was met at the door by Eichmann himself, who said that he was Klaus's uncle. Klaus arrived not long after, however, and addressed Eichmann as "Father". In 1957, Bauer passed along the information in person to Mossad Director Isser Harel, who assigned operatives to undertake surveillance, but no concrete evidence was initially found.

On 19 December 1939, Eichmann was assigned to head RSHA Referat IV B4 (RSHA Sub-Department IV-B4), tasked with overseeing Jewish affairs and evacuation. Heydrich announced Eichmann to be his "special expert", in charge of arranging for all deportations into occupied Poland. The job entailed co-ordinating with police agencies for the physical removal of the Jews, dealing with their confiscated property, and arranging financing and transport. Within a few days of his appointment, Eichmann formulated a plan to deport 600,000 Jews into the General Government. The plan was stymied by Hans Frank, governor-general of the occupied territories, who was disinclined to accept the deportees as to do so would have a negative impact on economic development and his ultimate goal of Germanisation of the region. In his role as minister responsible for the Four Year Plan, on 24 March 1940 Hermann Göring forbade any further transports into the General Government unless cleared first by himself or Frank. Transports continued, but at a much slower pace than originally envisioned. From the start of the war until April 1941, around 63,000 Jews were transported into the General Government. On many of the trains in this period, up to a third of the deportees died in transit. While Eichmann claimed at his trial to be upset by the appalling conditions on the trains and in the transit camps, his correspondence and documents of the period show that his primary concern was to achieve the deportations economically and with minimal disruption to Germany's ongoing military operations.

Jews were concentrated into ghettos in major cities with the expectation that at some point they would be transported further east or even overseas. Horrendous conditions in the ghettos—severe overcrowding, poor sanitation, and a lack of food—resulted in a high death rate. On 15 August 1940, Eichmann released a memorandum titled Reichssicherheitshauptamt: Madagaskar Projekt (Reich Main Security Office: Madagascar Project), calling for the resettlement to Madagascar of a million Jews per year for four years. When Germany failed to defeat the Royal Air Force in the Battle of Britain, the invasion of Britain was postponed indefinitely. As Britain still controlled the Atlantic and her merchant fleet would not be at Germany's disposal for use in evacuations, planning for the Madagascar proposal stalled. Hitler continued to mention the Plan until February 1942, when the idea was permanently shelved.

From the start of the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Einsatzgruppen (task forces) followed the army into conquered areas and rounded up and killed Jews, Comintern officials, and ranking members of the Communist Party. Eichmann was one of the officials who received regular detailed reports of their activities. On 31 July, Göring gave Heydrich written authorisation to prepare and submit a plan for a "total solution of the Jewish question" in all territories under German control and to co-ordinate the participation of all involved government organisations. The Generalplan Ost (General Plan for the East) called for deporting the population of occupied Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union to Siberia, for use as slave labour or to be murdered.

To co-ordinate planning for the proposed genocide, Heydrich hosted the Wannsee Conference, which brought together administrative Leaders of the Nazi regime on 20 January 1942. In preparation for the conference, Eichmann drafted for Heydrich a list of the numbers of Jews in various European countries and prepared statistics on emigration. Eichmann attended the conference, oversaw the stenographer who took the minutes, and prepared the official distributed record of the meeting. In his covering letter, Heydrich specified that Eichmann would act as his liaison with the departments involved. Under Eichmann's supervision, large-scale deportations began almost immediately to extermination camps at Bełżec, Sobibor, Treblinka and elsewhere. The genocide was code-named Operation Reinhard in honour of Heydrich, who died in Prague in early June from wounds suffered in an assassination attempt. Kaltenbrunner succeeded him as head of the RSHA.

On 24 December 1944, Eichmann fled Budapest just before the Soviets completed their encirclement of the capital. He returned to Berlin, where he arranged for the incriminating records of Department IV-B4 to be burned. Along with many other SS officers who fled in the closing months of the war, Eichmann and his family were living in relative safety in Austria when the war in Europe ended on 8 May 1945.

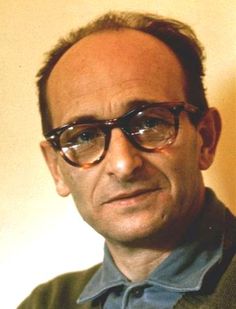

Throughout his cross-examination, prosecutor Hausner attempted to get Eichmann to admit he was personally guilty, but no such confession was forthcoming. Eichmann admitted to not liking the Jews and viewing them as adversaries, but stated that he never thought their annihilation was justified. When Hausner produced evidence that Eichmann had stated in 1945 that "I will leap into my grave laughing because the feeling that I have five million human beings on my conscience is for me a source of extraordinary satisfaction", Eichmann said he meant "enemies of the Reich" such as the Soviets. During later examination by the judges, he admitted he meant the Jews, and said the remark was an accurate reflection of his opinion at the time.

In 1948, Eichmann obtained a landing permit for Argentina and false identification under the name of "Ricardo Klement" through an organisation directed by Bishop Alois Hudal, an Austrian cleric then residing in Italy with known Nazi sympathies. These documents enabled him to obtain an International Committee of the Red Cross humanitarian passport and the remaining entry permits in 1950 that would allow emigration to Argentina. He travelled across Europe, staying in a series of monasteries that had been set up as safe houses. He departed from Genoa by ship on 17 June 1950 and arrived in Buenos Aires on 14 July.

Eichmann initially lived in Tucumán Province, where he worked for a government contractor. He sent for his family in 1952, and they moved to Buenos Aires. He held a series of low-paying jobs until finding employment at Mercedes-Benz, where he rose to department head. The family built a house at 14 Garibaldi Street (now 6061 Garibaldi Street) and moved in during 1960. He was extensively interviewed for four months beginning in late 1956 by Nazi expatriate Journalist Willem Sassen with the intention of producing a biography. Eichmann produced tapes, transcripts, and handwritten notes. The memoirs were later used as the basis for a series of articles that appeared in Life and Der Stern magazines in late 1960.

Several survivors of the Holocaust dedicated themselves to finding Eichmann and other Nazis, and among them was Jewish Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal. Wiesenthal learned from a letter shown to him in 1953 that Eichmann had been seen in Buenos Aires, and he passed along that information to the Israeli consulate in Vienna in 1954. Eichmann's father died in 1960, and Wiesenthal made arrangements for private detectives to surreptitiously photograph members of the family; Eichmann's brother Otto was said to bear a strong family resemblance and there were no current photos of the fugitive. He provided these photographs to Mossad agents on 18 February.

Argentina requested an urgent meeting of the United Nations Security Council in June 1960, after unsuccessful negotiations with Israel, as they regarded the capture as a violation of their sovereign rights. In the ensuing debate, Israeli representative Golda Meir claimed that the abductors were not Israeli agents but private individuals and so the incident was only an "isolated violation of Argentine law". On 23 June, the Council passed Resolution 138 which agreed that Argentine sovereignty had been violated and requested that Israel should make reparations. Israel and Argentina issued a joint statement on 3 August, after further negotiations, admitting the violation of Argentinian sovereignty but agreeing to end the dispute. The Israeli court determined that the circumstances of his capture had no bearing on the legality of his trial.

The trial adjourned on 14 August, and the verdict was read on 12 December. The judges declared him not guilty of personally killing anyone and not guilty of overseeing and controlling the activities of the Einsatzgruppen. He was deemed responsible for the dreadful conditions on board the deportation trains and for obtaining Jews to fill those trains. He was found guilty of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes against Poles, Slovenes and Gypsies. He was also found guilty of membership in three organisations that had been deemed Criminal at the Nuremberg trials: the Gestapo, the SD, and the SS. When considering the sentence, the judges concluded that Eichmann had not merely been following orders, but believed in the Nazi cause wholeheartedly and had been a key perpetrator of the genocide. On 15 December 1961, Eichmann was sentenced to death by hanging.

Eichmann was hanged at a prison in Ramla hours later. The hanging, scheduled for midnight at the end of 31 May, was slightly delayed and thus took place a few minutes past 12:00 a.m. on 1 June 1962. The execution was attended by a small group of officials, four journalists and the Canadian clergyman william Lovell Hull, who had been his spiritual counselor while in prison. His last words were:

Hannah Arendt, a political theorist who reported on Eichmann's trial for The New Yorker, described Eichmann in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem as the embodiment of the "banality of evil", as she thought he appeared to have an ordinary personality, displaying neither guilt nor hatred. Arendt also wrote that "this case was built on what the Jews had suffered, not on what Eichmann had done." In his 1988 book Justice, Not Vengeance, Wiesenthal said: "The world now understands the concept of 'desk murderer'. We know that one doesn't need to be fanatical, sadistic, or mentally ill to murder millions; that it is enough to be a loyal follower eager to do one's duty." The term "little Eichmanns" became a pejorative term for bureaucrats charged with indirectly and systematically harming others.

US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) documents declassified in 2006 show that the capture of Eichmann caused alarm at the CIA and West German Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND). Both organisations had known for at least two years that Eichmann was hiding in Argentina, but they did not act because it did not serve their interests in the Cold War to do so. Both were concerned about what Eichmann might say in his testimony about West German national security advisor Hans Globke, who had coauthored several antisemitic Nazi laws, including the Nuremberg Laws. The documents also revealed that both agencies had used some of Eichmann's former Nazi colleagues to spy on European Communist countries.

Eichmann was taken to one of several Mossad safe houses that had been set up by the team. He was held there for nine days, during which time his identity was double-checked and confirmed. During these days, Harel tried to locate Josef Mengele, the notorious Nazi Doctor from Auschwitz, as the Mossad had information that he was also living in Buenos Aires. He was hoping to bring Mengele back to Israel on the same FLIGHT. However, Mengele had already left his last known residence in the city, and Harel was unable to get any leads on where he had gone, so the plans for his capture had to be abandoned. Eitan told Haaretz in 2008 that they intentionally made the decision not to pursue Mengele, reasoning that to do so might jeopardise the Eichmann operation.

In her 2011 book Eichmann Before Jerusalem, based largely on the Sassen interviews and Eichmann's notes made while in exile, Bettina Stangneth argues instead that Eichmann was an ideologically motivated antisemite and lifelong committed Nazi who intentionally built a persona as a faceless bureaucrat for presentation at the trial. Prominent historians such as Christopher Browning, Deborah Lipstadt, Yaacov Lozowick, and David Cesarani reached a similar conclusion, that Eichmann was not the unthinking bureaucratic functionary that Arendt believed him to be.

The defence next engaged in a lengthy direct examination of Eichmann. Observers such as Moshe Pearlman and Hannah Arendt have remarked on Eichmann's ordinariness in appearance and flat affect. In his testimony throughout the trial, Eichmann insisted he had no choice but to follow orders, as he was bound by an oath of loyalty to Hitler – the same superior orders defence used by some defendants in the 1945–1946 Nuremberg trials. Eichmann asserted that the decisions had been made not by him, but by Müller, Heydrich, Himmler, and ultimately Hitler. Servatius also proposed that decisions of the Nazi government were acts of state and therefore not subject to normal judicial proceedings. Regarding the Wannsee Conference, Eichmann stated that he felt a sense of satisfaction and relief at its conclusion. As a clear decision to exterminate had been made by his superiors, the matter was out of his hands; he felt absolved of any guilt. On the last day of the examination, he stated that he was guilty of arranging the transports, but he did not feel guilty for the consequences.

Eichmann was taken to a fortified police station at Yagur in Israel, where he spent nine months. The Israelis were unwilling to take him to trial based solely on the evidence in documents and witness testimony, so the prisoner was subject to daily interrogations, the transcripts of which totalled over 3,500 pages. The interrogator was Chief Inspector Avner Less of the national police. Using documents provided primarily by Yad Vashem and Nazi hunter Tuviah Friedman, Less was often able to determine when Eichmann was lying or being evasive. When additional information was brought forward that forced Eichmann into admitting what he had done, Eichmann would insist he had not had any authority in the Nazi hierarchy and had only been following orders. Inspector Less noted that Eichmann did not seem to realise the enormity of his crimes and showed no remorse. His pardon plea, released in 2016, did not contradict this: "There is a need to draw a line between the Leaders responsible and the people like me forced to serve as mere instruments in the hands of the leaders", Eichmann wrote. "I was not a responsible leader, and as such do not feel myself guilty."