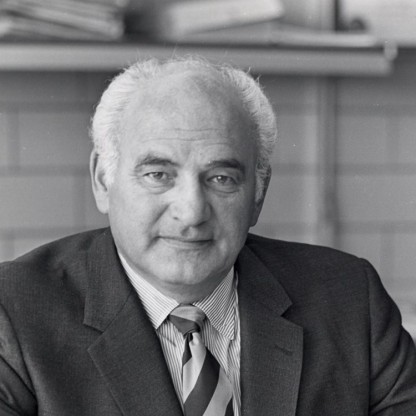

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Cardiac Surgeon |

| Birth Day | October 04, 1918 |

| Birth Place | New York, United States |

| Age | 102 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | November 14, 2008(2008-11-14) (aged 90)\nAnn Arbor, Michigan, United States |

| Birth Sign | Scorpio |

| Known for | left ventricular assist device, heart transplantation |

| Fields | cardiac surgeon |

| Institutions | L.VAD Technology, Inc. |

Net worth

Adrian Kantrowitz, renowned as a cardiac surgeon in the United States, is projected to have a net worth of $100K to $1M in 2024. Dr. Kantrowitz has gained significant recognition for his expertise and groundbreaking contributions to the field of heart surgery. Known for his innovation and pioneering spirit, he has played a crucial role in developing cardiac transplantation and the concept of mechanical circulatory support. As his career continues to flourish, his net worth is anticipated to reflect his immense professional accomplishments and contributions to the medical community.

Biography/Timeline

Kantrowitz was born in New York City on October 4, 1918. His mother was a costume designer and his Father ran a clinic in the Bronx. Adrian told his mother as a three-year-old that he wanted to be a Doctor, and as a child built an electrocardiograph from old radio parts, together with his brother Arthur.

He graduated from New York University in 1940, having majored in math. He attended the Long Island College of Medicine (now SUNY Downstate Medical Center) and was awarded his medical degree in 1943 as part of an effort to accelerate the availability of Physicians during World War II. During an internship at the Jewish Hospital of Brooklyn, he developed an interest in neurosurgery, and had a paper published in 1944, "A Method of Holding Galea Hemostats in Craniotomies", in which he proposed a new type of clamp to be used while performing a craniotomy during brain surgery.

He served for two years as a battalion surgeon in the United States Army Medical Corps. Kantrowitz was discharged from the Army in 1946 with the rank of major.

After his military Service, he switched to specialize in cardiac surgery due to the paucity of positions in neurosurgery. In 1947, he was an Assistant Resident in Surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan.

Kantrowitz married Jean Rosensaft on November 25, 1948. His wife was an administrator on the surgical research laboratories at Maimonides Medical Center while he was there. In 1983, they co-founded L.VAD Technology, Inc., a company specializing in research and development of cardiovascular devices, with Dr. Kantrowitz as President and his wife as vice President.

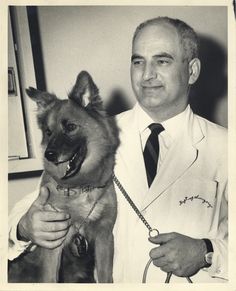

He was on the surgical staff of Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx from 1948 until 1955. He started at Montefiore as Assistant Resident in Surgery and Pathology, and progressed to Cardiovascular Research Fellow before becoming Chief Resident in Surgery. At the New York Academy of Medicine, on October 16, 1951, he screened the world's first movies taken inside a living heart, showing the sequential opening and closing of the mitral valve inside a beating heart. Using dogs and other animals as experimental subjects, Kantrowitz developed an artificial left heart, an early version of an oxygen generator for use as a component in a heart-lung machine and a treatment for coronary artery disease in which blood vessels would be rearranged during surgery. He also developed a device that allowed individuals who were paralyzed to have their bladders empty through a signal sent from a radio-controlled device.

From 1955 to 1970, he held surgical posts at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn. In February 1958, a heart-lung machine Kantrowitz had developed was used during open heart surgery on a six-year-old boy while the Surgeons repaired a one-inch hole between the chambers of the boy's heart that was present since birth. In an October 1959 lecture at the American College of Surgeons, Kantrowitz and colleague Dr. william M. P. McKinnon reported on a procedure in which a portion of muscle from the diaphragm was used to create a "booster" heart to help pump blood in a dog, taking over as much as 25% of the pumping burden of the natural heart. The booster heart functions by receiving a signal sent by a radio transmitter triggered by the pulse of the natural heart. Kantrowitz noted that the procedure was not ready to be performed on humans. Ruff, a "friendly dog of unknown ancestry" was honored by the New York Academy of Sciences as "research dog of the year" for his unwitting participation in the implantation of a booster heart 18 months earlier in a procedure performed by Kantrowitz.

In the early 1960s, Kantrowitz developed an implantable artificial pacemaker together with General Electric. The first of these pacemakers was implanted in May 1961. The device included an external control unit that could adjust the pacing rate from 64 to 120 beats per minute to allow the patient to deal with physical or emotional stress.

Dr. James Hardy had performed the world's first heart transplant attempt and first heart xenograft at the University of Mississippi Medical Center on Jan. 24, 1964. Since there was no standard of brain death, Hardy had acquired four chimpanzees as potential back-up donors. A comatose Boyd Rush with a faint pulse had been brought to the hospital several days earlier and when he went into shock and was taken into surgery, Hardy polled the fellow doctors on his team, with three voting yes and one abstaining. Hardy and his team then proceeded with the transplant using a chimpanzee heart which beat in Rush's chest approximately 60 to 90 minutes (sources vary), and Rush died without regaining consciousness. The hospital's public relations department put out a guarded statement, with many of the early newspaper articles making the assumption that the donor was a human. In addition, when Hardy attended the Sixth International Transplantation Conference several weeks later, he was treated with "icy disdain." Hardy withdrew from active pursuit of a successful heart transplant.

In what turned out to be a four-way race between South African cardiac surgeon Dr. Christiaan Barnard and Americans Norman Shumway and Richard Lower, Kantrowitz prepared for a potential human heart transplant by transplanting hearts in 411 dogs over a five-year period together with members of his surgical team. On June 29, 1966, by which time Kantrowitz had completed the necessary technical research, one of his patients was an 18-day-old infant who very much needed a new heart. He and his team had located an anecephalic baby whose parents agreed to let her be the donor. Due to disagreements with senior staffers Howard Joos and Harry Weiss, Kantrowitz was forced to wait until cardiac death (instead of the more modern use of brain death) to retrieve the donor heart, which was found to be useless. According to the Every Second Counts: The Race to Transplant the First Human Heart (2006), Kantrowitz did not know at the time that the donor parents in Oregon both expected and wanted their baby's heart to be taken before it stopped beating (anecephalic babies typically live 24 to 48 hours). Barnard performed the first human-to-human heart transplant with an adult donor and recipient on December 3, 1967 at Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa.

The intra-aortic balloon pump was invented by Adrian Kantrowitz, working in conjunction with his brother, Arthur Kantrowitz. Inserted through the patient's thigh, it was directed into the aorta, and alternately expanded and contracted in order to reduce strain on the heart. Based on Kantrowitz's theory of "counterpulsation", the device inflated the balloon with helium gas when the heart relaxed and deflated it when the heart pumped blood. The pump did not require surgery and could be inserted using local anesthetic in an emergency room or at a patient's bedside. The device was first used in August 1967 to save the life of a 45-year-old woman who was having a heart attack. The device could be used in the 15% of heart attack patients who went into severe shock, 80% of whom could not be helped by the protocols that existed before the balloon pump. Since the device went into widespread use in the 1980s, it had been used in some three million patients by the time of his death.

At Sinai Hospital, Kantrowitz experimented further with heart transplants and continued development of the balloon pump, and partial mechanical hearts. In August 1971, he implanted an artificial heart booster in a 63-year-old man whose weakened heart could not pump sufficient oxygenated blood to his body. The patient became the first partial mechanical heart patient to be sent home, and died three months after the surgery.

In 1981, Kantrowitz became a founding member of the World Cultural Council.

Kantrowitz died at age 90 in Ann Arbor, Michigan on November 14, 2008 of heart failure.