Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | American dancer and choreographer |

| Birth Day | September 18, 1905 |

| Birth Place | New York City, United States |

| Age | 115 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | October 7, 1993(1993-10-07) (aged 88)\nNew York City, New York, US |

| Birth Sign | Libra |

| Occupation | Choreographer, dancer |

| Years active | 1910s–1990s |

Net worth: $1.4 Million (2024)

Agnes de Mille, a renowned American dancer and choreographer, is estimated to have a net worth of $1.4 million in 2024. With a tremendous contribution to the field of dance, de Mille has left an indelible mark on the art form in the United States. Known for her innovative choreography and storytelling techniques, she has elevated dance to new heights through her unique style and creativity. With a successful career spanning several decades, de Mille's net worth is a testament to her talent and the impact she has had on the world of dance.

Biography/Timeline

De Mille graduated from UCLA with a degree in English where she was a member of Kappa Alpha Theta sorority, and in 1933 moved to London to study with Dame Marie Rambert, eventually joining Rambert's company, The Ballet Club, later Ballet Rambert, and Antony Tudor's London Ballet.

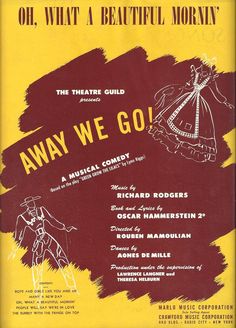

De Mille began her association with the fledgling American Ballet Theatre (then called the Ballet Theatre) in 1939, but her first significant work, Rodeo (1942) with the score by Aaron Copland, was staged for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Although de Mille continued to choreograph nearly up to the time of her death—her final ballet, The Other, was completed in 1992—most of her later works have dropped out of the ballet repertoire. Besides Rodeo, two other de Mille ballets are performed on a regular basis, Three Virgins and a Devil (1934) adapted from a tale by Giovanni Boccaccio, and Fall River Legend (1948) based on the life of Lizzie Borden.

De Mille married Walter Prude on June 14, 1943. They had one child, Jonathan, born in 1946.

DeMille's 1951 memoir, Dance to the Piper, was translated into five languages. It was reissued in 2015 by New York Review Books.

De Mille's success on Broadway did not translate into success in Hollywood. Her only significant film credit is Oklahoma! (1955). She was not invited to recreate her choreography for either Brigadoon (1954) or Carousel (1956). Nevertheless, her two specials for the Omnibus TV series entitled "The Art of Ballet" and "The Art of Choreography" (both televised in 1956) were immediately recognized as landmark attempts to bring serious dance to the attention of a broad public.

Agnes De Mille was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame in 1973. De Mille's many other awards include the Tony Award for Best Choreography (1947, for Brigadoon), the Handel Medallion for achievement in the arts (1976), an honor from the Kennedy Center (1980), an Emmy for her work in The Indomitable de Mille (1980), Drama Desk Special Award (1986) and, in 1986, she was awarded the National Medal of Arts. De Mille also has received seven honorary degrees from various colleges and universities.

She suffered a stroke on stage in 1975, but recovered. She died in 1993 of a second stroke in her Greenwich Village apartment.

She was interviewed in the television documentary series Hollywood: A Celebration of the American Silent Film (1980) primarily discussing the work of her uncle Cecil B. DeMille.

At present, the only commercially available examples of de Mille's choreography are parts one and two of Rodeo by the American Ballet Theater, Fall River Legend (filmed in 1989 by the Dance Theatre of Harlem) and Oklahoma!

De Mille was a lifelong friend of modern dance legend Martha Graham. De Mille, in 1992, published Martha: The Life and Work of Martha Graham, a biography of Graham that de Mille worked on for more than thirty years.

She had a love for acting and originally wanted to be an Actress, but was told that she was "not pretty enough", so she turned her attention to dance. As a child, she had longed to dance, but dance at this time was considered more of an activity, rather than a viable career option, so her parents refused to allow her to dance. She did not seriously consider dancing as a career until after she graduated from college. When de Mille's younger sister was prescribed ballet classes to cure her flat feet, de Mille joined her. De Mille lacked flexibility and technique, though, and did not have a dancer's body. Classical ballet was the most widely known dance form at this time, and de Mille's apparent lack of ability limited her opportunities. She taught herself from watching film stars on the set with her Father in Hollywood; these were more interesting for her to watch than perfectly turned out legs, and she developed strong character work and compelling performances. One of de Mille’s earliest jobs, thanks to her father’s connections, was choreographing the Cecil B. DeMille film Cleopatra (1934). DeMille's dance Director LeRoy Prinz clashed with the younger de Mille. Her uncle always deferred to Prinz, even after agreeing to his niece's dances in advance, and Agnes de Mille left the film.