Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Editor |

| Birth Day | November 21, 1870 |

| Birth Place | Vilnius, Russian |

| Age | 149 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | June 28, 1936(1936-06-28) (aged 65)\nNice, France |

| Birth Sign | Sagittarius |

| Cause of death | Suicide |

| Burial place | Cochez Cemetery, Nice, France |

| Occupation | Writer Anti-war and political activist |

Net worth

Alexander Berkman's net worth is projected to be between $100,000 and $1 million in 2024. He gained prominence as an influential figure within the Russian revolutionary movement and was regarded as an editor. While his exact net worth might be subject to change, it is evident that Berkman's contributions to the Russian editorial landscape have earned him considerable wealth and recognition.

Famous Quotes:

Will you proclaim to the world that you who carry liberty and democracy to Europe have no liberty here, that you who are fighting for democracy in Germany, suppress democracy right here in New York, in the United States? Are you going to suppress free speech and liberty in this country, and still pretend that you love liberty so much that you will fight for it five thousand miles away?

Biography/Timeline

Soon after Berkman turned 12, his Father died. The Business had to be sold, and the family lost the right to live in Saint Petersburg. Yetta moved the family to Kovno, where her brother Nathan lived. Berkman had shown great promise as a student at the gymnasium, but his studies began to falter as he spent his time reading novels. One of the books that interested him was Ivan Turgenev's novel Fathers and Sons (1862), with its discussion of nihilist philosophy. But what truly moved him was Nikolay Chernyshevsky's 1863 novel, What Is to Be Done?, and Berkman felt inspired by Rakhmetov, its puritanical protagonist who is willing to sacrifice personal pleasure and family ties in single-minded pursuit of his revolutionary aims.

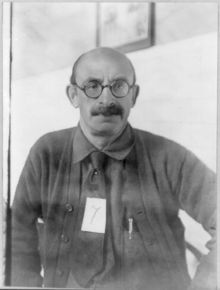

In 1877, Osip Berkman was granted the right, as a successful businessman, to move from the Pale of Settlement to which Jews were generally restricted in the Russian Empire. The family moved to Saint Petersburg, a city previously off-limits to Jews. There, Ovsei adopted the more Russian name Alexander; he was known among family and friends as Sasha, a diminutive for Alexander. The Berkmans lived comfortably, with servants and a summer house. Berkman attended the gymnasium, where he received a classical education with the youth of Saint Petersburg's elite.

As a youth, Berkman was influenced by the growing radicalism that was spreading among workers in the Russian capital. A wave of political assassinations culminated in a bomb blast that killed Tsar Alexander II in 1881. While his parents worried—correctly, as it turned out—that the tsar's death might result in repression of the Jews and other minorities, Berkman became intrigued by the radical ideas of the day, including populism and nihilism. He became very upset when his favorite uncle, his mother's brother Mark Natanson, was sentenced to death for revolutionary activities.

Soon after his arrival in New York, where he knew nobody and spoke no English, Berkman became an anarchist through his involvement with groups that had formed to campaign to free the men convicted of the 1886 Haymarket bombing. He joined the Pioneers of Liberty, the first Jewish anarchist group in the U.S. The group was affiliated with the International Working People's Association, the organization to which the Haymarket defendants had belonged, and they regarded the Haymarket men as martyrs. Since most of its members worked in the garment industry, the Pioneers of Liberty took part in strikes against sweatshops and helped establish some of the first Jewish labor unions in the city. Before long, Berkman was one of the prominent members of the organization.

Berkman's mother died in 1887 (he was 18), and his uncle Nathan Natanson became responsible for him. Berkman had contempt for Natanson for his Desire to maintain order and avoid conflict. Natanson could not understand what Berkman found appealing in his radical ideas, and he worried that Berkman would bring shame to the family. Late that year, Berkman was caught stealing copies of the school exams and bribing a handyman. He was expelled and labelled a "nihilist conspirator".

In 1889, Berkman met and began a romance with Emma Goldman, another Russian immigrant. He invited her to Most's lecture. Soon Berkman and Goldman fell in love and became inseparable. Despite their disagreements and separations, Goldman and Berkman would share a mutual devotion for decades, united by their anarchist principles and love for each other.

At the end of 1891, Berkman learned that Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin, whom he admired, had canceled an American speaking tour on the basis that it was too expensive for the struggling anarchist movement. While Berkman was disappointed, the frugality of the action further elevated Kropotkin's stature in his eyes.

Within weeks of his arrival at prison, Berkman began planning his suicide. He tried to sharpen a spoon into a blade, but his attempt was discovered by a guard and Berkman spent the night in the dungeon. He thought about beating his head against the bars of his cell, but worried that his efforts might injure him but leave him alive. Berkman wrote a letter to Goldman, asking her to secure a dynamite capsule for him. A letter was smuggled out of the prison and arrangements were made for her to visit Berkman in November 1892, posing as his sister. Berkman knew as soon as he saw Goldman that she had not brought the dynamite capsule.

Between 1893 and 1897, the years when Bauer and Nold were also in the Western Penitentiary for their part in the assassination attempt, the three men surreptitiously produced 60 issues of a hand-written anarchist newsletter by transferring their work from cell to cell. They managed to send the completed newsletters, which they called Prison Blossoms, to friends outside the prison. Participating in Prison Blossoms, initially written in German and later in English, helped Berkman improve his English. He developed a friendship with the prison chaplain, John Lynn Milligan, who was a strong advocate on behalf of the prison library. Milligan encouraged Berkman to read books from the library, a process that furthered his knowledge of English.

In 1897, as Berkman finished the fifth year of his sentence, he applied to the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons. Having served as his own attorney, Berkman had failed to object to the trial judge's rulings and thus had no legal basis for an appeal; a pardon was his only hope for early release. The Board of Pardons denied his application in October 1897. A second application was rejected in early 1899.

Now an escape seemed like Berkman's only option. The plan was to rent a house across the street from the prison and dig an underground tunnel from the house to the prison. Berkman had been given access to a large portion of the prison and had grown familiar with its layout. In April 1900, a house was leased. The tunnel would be dug from the cellar of the house to the stable inside the prison yard. When the digging was complete, Berkman would sneak into the stable, tear open the wooden flooring, and crawl through the tunnel to the house.

In 1905, Berkman was transported from the Western Penitentiary to the Allegheny County Workhouse, where he spent the final 10 months of his sentence. He found conditions in the workhouse "a nightmare of cruelty, infinitely worse than the most inhuman aspects of the penitentiary." The guards beat inmates for the slightest provocation, and one particularly sadistic guard shoved prisoners down the stairs. Berkman felt mixed emotions; he was concerned about the friends he had made in the prison, he was excited about the prospect of freedom, and he was worried about what life as a free man would be like.

Berkman was released from the workhouse on May 18, 1906, after serving 14 years of his sentence. He was met at the workhouse gates by newspaper reporters and police, who recommended that he leave the area. He took the train to Detroit, where Goldman met him. She found herself "seized by terror and pity" at his gaunt appearance. Later, at a friend's house, Berkman felt overwhelmed by the presence of well-wishers. He became claustrophobic and almost suicidal. Nevertheless, he agreed to a joint lecture tour with Goldman.

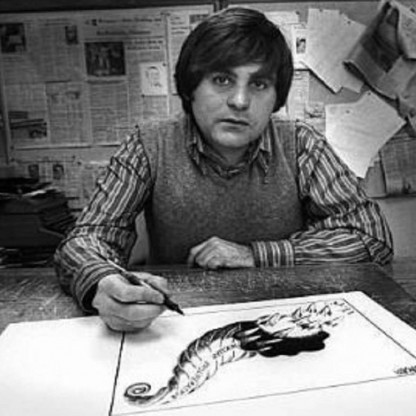

After resting for several months, Berkman began to recover. He remained anxious about his lack of employment. He considered returning to his old job as a printer, but his skills had become obsolete in light of innovations in linotype machines. With Goldman's encouragement, Berkman began to write an account of his prison years, Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, and she invited him to become the Editor of her journal, Mother Earth. He served as Editor from 1907 to 1915, and took the journal in a more provocative and practical direction, in contrast to the more theoretical approach which had been favored by the previous Editor, Max Baginski. Under Berkman's stewardship, circulation of Mother Earth rose as high as 10,000 and it became the leading anarchist publication in the U.S.

Berkman helped establish the Ferrer Center in New York during 1910 and 1911, and served as one of its teachers. The Ferrer Center, named in honor of Spanish anarchist Francisco Ferrer, included a free school that encouraged independent thinking among its students. The Ferrer Center also served as a community center for adults.

In September 1913, the United Mine Workers called a strike against coal-mining companies in Ludlow, Colorado. The largest mining company was the Rockefeller family-owned Colorado Fuel & Iron Company. On April 20, 1914, the Colorado National Guard attacked a tent colony of striking miners and their families and, during a day-long fight, 26 people were killed.

In late 1915, Berkman left New York and went to California. In San Francisco the following year, he started his own anarchist journal, The Blast. Although it was published for just 18 months, The Blast was considered second only to Mother Earth in its influence among U.S. anarchists.

On July 22, 1916, a bomb exploded during the San Francisco Preparedness Day Parade, killing ten people and wounding 40. Police suspected Berkman, although there was no evidence, and ultimately their investigation focused on two local labor Activists, Thomas Mooney and Warren Billings. Although neither Mooney nor Billings were anarchists, Berkman came to their aid: raising a defense fund, hiring lawyers, and beginning a national campaign on their behalf. Mooney and Billings were convicted, with Mooney sentenced to death and Billings to life imprisonment.

Berkman and Goldman were released at the height of the first U.S. Red Scare; the Russian Revolutions of 1917, combined with anxiety about the war, produced a climate of anti-radical and anti-foreign sentiment. The U.S. Justice Department's General Intelligence Division, headed by J. Edgar Hoover and under the direction of Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer, initiated a series of raids to arrest leftists. While they were in prison, Hoover wrote: "Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman are, beyond doubt, two of the most dangerous anarchists in this country and if permitted to return to the community will result in undue harm." Under the 1918 Anarchist Exclusion Act, the government deported Berkman, who had never applied for U.S. citizenship, along with Goldman and more than two hundred others, to Russia aboard the Buford.

The jury found them guilty and Judge Julius M. Mayer imposed the maximum sentence: two years' imprisonment, a $10,000 fine, and the possibility of deportation after their release from prison. Berkman served his sentence in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, seven months of which were in solitary confinement for protesting the beating of other inmates. When he was released on October 1, 1919, Berkman looked "haggard and pale"; according to Goldman, the 21 months Berkman served in Atlanta took a greater toll on him than his 14-year incarceration in Pennsylvania.

Berkman and Goldman spent much of 1920 traveling through Russia collecting material for a proposed Museum of the Revolution. As the pair traveled around the country, they found repression, mismanagement, and corruption instead of the equality and worker empowerment they had dreamed of. Those who questioned the government were demonized as counter-revolutionaries, and workers labored under severe conditions. They met with Lenin, who assured them that government suppression of press liberties was justified. "When the Revolution is out of danger," he told them, "then free speech might be indulged in".

Berkman and Goldman left the country in December 1921. Berkman moved to Berlin and almost immediately began to write a series of pamphlets about the Russian Revolution. "The Russian Tragedy", "The Russian Revolution and the Communist Party", and "The Kronstadt Rebellion" were published during the summer of 1922.

Berkman planned to write a book about his experience in Russia, but he postponed it while he assisted Goldman as she wrote a similar book, using as sources material he had collected. Work on Goldman's book, My Two Years in Russia, was completed in December 1922, and the book was published in two parts with titles not of her choosing: My Disillusionment in Russia (1923) and My Further Disillusionment in Russia (1924). Berkman worked on his book, The Bolshevik Myth, throughout 1923 and it was published in January 1925.

Berkman moved to Saint-Cloud, France, in 1925. He organized a fund for aging anarchists including Sébastien Faure, Errico Malatesta, and Max Nettlau. He continued to fight on behalf of anarchist prisoners in the Soviet Union, and arranged the publication of Letters from Russian Prisons, which detailed their persecution.

In 1926, the Jewish Anarchist Federation of New York asked Berkman to write an introduction to anarchism intended for the general public. By presenting the principles of anarchism in plain language, the New York anarchists hoped that readers might be swayed to support the movement or, at a minimum, that the book might improve the image of anarchism and anarchists in the public's eyes. Berkman produced Now and After: The ABC of Communist Anarchism, first published in 1929 and reprinted many times since (often under the title What Is Communist Anarchism? or What Is Anarchism?). Anarchist Stuart Christie wrote that Now and After is "among the best introductions to the ideas of anarchism in the English language" and Historian Paul Avrich described it as "the clearest exposition of communist anarchism in English or any other language".

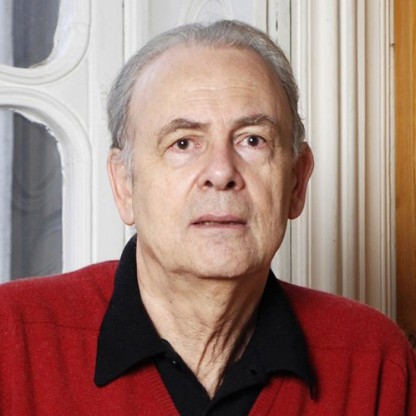

Berkman spent his last years eking out a precarious living as an Editor and translator. He and his companion, Emmy Eckstein, relocated frequently within Nice in search of smaller and less expensive quarters. Aronstam, who had changed his name to Modest Stein and attained success as an Artist, became a benefactor, sending Berkman a monthly sum to help with expenses. In the 1930s his health began to deteriorate, and he underwent two unsuccessful operations for a prostate condition in early 1936. After the second surgery, he was bed-ridden for months. In constant pain, forced to rely on the financial help of friends and dependent on Eckstein's care, Berkman decided to commit suicide. In the early hours of June 28, 1936, unable to endure the physical pain of his ailment, Berkman tried to shoot himself in the heart with a handgun, but he failed to make a clean job of it. The bullet punctured a lung and his stomach and lodged in his spinal column, paralyzing him. Goldman rushed to Nice to be at his side. Berkman recognized her but was unable to speak. He sank into a coma in the afternoon, and died at 10 o'clock that night.

While living in France, Berkman continued his work in support of the anarchist movement, producing the classic exposition of anarchist principles, Now and After: The ABC of Communist Anarchism. Suffering from ill health, Berkman committed suicide in 1936.

Berkman died weeks before the start of the Spanish Revolution, modern history's clearest Example of an anarcho-syndicalist revolution. In July 1937, Goldman wrote that seeing his principles in practice in Spain "would have rejuvenated [Berkman] and given him new strength, new hope. If only he had lived a little longer!"

Berkman arranged for Russian anarchists to protest outside the American embassy in Petrograd during the Russian Revolution, which led U.S. President Woodrow Wilson to ask California's governor to commute Mooney's death sentence. When the governor reluctantly did so, he said that "the propaganda in [Mooney's] behalf following the plan outlined by Berkman has been so effective as to become world-wide." Billings and Mooney both were pardoned in 1939.

In July, three associates of Berkman—Charles Berg, Arthur Caron, and Carl Hanson—began collecting dynamite and storing it at the apartment of another conspirator, Louise Berger. Some sources, including Charles Plunkett, one of the surviving conspirators, say that Berkman was the chief conspirator, the oldest and most experienced member of the group. Berkman denied any involvement or knowledge of the plan.