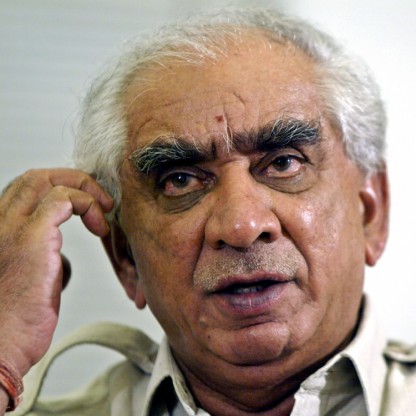

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Politician |

| Birth Day | November 27, 1921 |

| Birth Place | Uhrovec, Slovak |

| Age | 99 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 7 November 1992(1992-11-07) (aged 70)\nPrague, Czechoslovakia\n(now Czech Republic) |

| Birth Sign | Sagittarius |

| Preceded by | Peter Colotka |

| Succeeded by | Dalibor Hanes |

| Political party | Communist Party of Slovakia (1939–1948) Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (1948–1970) Public Against Violence (1989–1992) Social Democratic Party of Slovakia (1992) |

Net worth: $850,000 (2024)

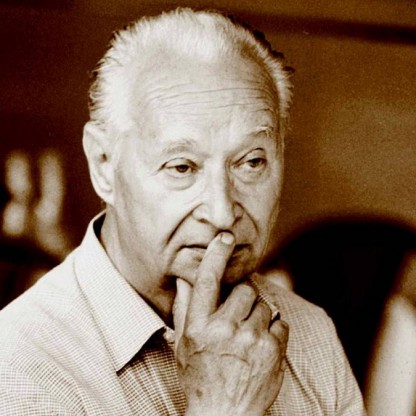

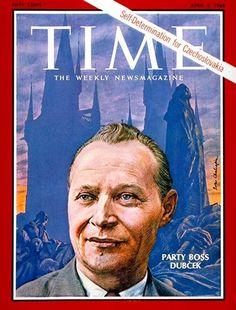

Alexander Dubcek's net worth is estimated to be $850,000 in 2024. He is widely recognized as a prominent politician in Slovakia. Dubcek garnered immense fame and popularity for his significant contributions to the political landscape of the country. Known for his progressive thinking and reformative approach, he played a pivotal role in the 1968 Prague Spring movement, which aimed to bring about political liberalization in Czechoslovakia. Despite facing political adversity and repression during his career, Dubcek remained steadfast in his ideals and principles. Today, his accomplishments have not only earned him admiration but have also contributed to his financial success, resulting in his noteworthy net worth.

Biography/Timeline

Alexander Dubček was born in Czechoslovakia on 27 November 1921. When he was three, the family moved to the Soviet Union, in part to help build socialism and in part because jobs were scarce in Czechoslovakia; so that he was raised until 12 in the Kirghiz SSR of the Soviet Union (now Kyrgyzstan) as a member of the Esperantist and Idist industrial cooperative Interhelpo. In 1933, the family moved to Gorky, and in 1938 returned to Czechoslovakia.

During the Second World War, Alexander Dubček joined the underground resistance against the wartime pro-German Slovak state headed by Jozef Tiso. In August 1944, Dubček fought in the Slovak National Uprising and was wounded twice, while his brother, Július, was killed.

Under Dubček's leadership, Slovakia began to evolve toward political liberalization. Because Novotný and his Stalinist predecessors had denigrated Slovak "bourgeois nationalists", most notably Gustáv Husák and Vladimír Clementis, in the 1950s, the Slovak branch worked to promote Slovak identity. This mainly took the form of celebrations and commemorations, such as the 150th birthdays of 19th century Leaders of the Slovak National Revival Ľudovít Štúr and Jozef Miloslav Hurban, the centenary of the Matica slovenská in 1963, and the twentieth anniversary of the Slovak National Uprising. At the same time, the political and intellectual climate in Slovakia became freer than that in the Czech Lands. This was exemplified by the rising readership of Kultúrny život, the weekly newspaper of the Union of Slovak Writers, which published frank discussions of liberalization, federalization and democratization, written by the most progressive or controversial Writers – both Slovak and Czech. Kultúrny život consequently became the first Slovak publication to gain a wide following among Czechs.

After the war, he steadily rose through the ranks in Communist Czechoslovakia. From 1951 to 1955 he was a member of the National Assembly, the parliament of Czechoslovakia. In 1953, he was sent to the Moscow Political College, where he graduated in 1958. In 1955 he joined the Central Committee of the Slovak branch and in 1962 became a member of the presidium. In 1958 he also joined the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, which he served as a secretary from 1960 to 1962 and as a member of the presidium after 1962. From 1960 to 1968 he once more was a member of the federal parliament.

The Soviet leadership tried to slow down or stop the changes in Czechoslovakia through a series of negotiations. The Soviet Union agreed to bilateral talks with Czechoslovakia in July at Čierna nad Tisou, near the Slovak-Soviet border. At the meeting, Dubček tried to reassure the Soviets and the Warsaw Pact Leaders that he was still friendly to Moscow, arguing that the reforms were an internal matter. He thought he had learned an important lesson from the failing of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, in which the Leaders had gone as far as withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact. Dubček believed that the Kremlin would allow him a free hand in pursuing domestic reform as long as Czechoslovakia remained a faithful member of the Soviet bloc. Despite Dubček's continuing efforts to stress these commitments, Brezhnev and other Warsaw Pact Leaders remained wary, seeing a free press as threatening an end to one-party rule in Czechoslovakia, and (by extension) elsewhere in Eastern Europe.

In 1963, a power struggle in the leadership of the Slovak branch unseated Karol Bacílek and Pavol David, hard-line allies of Antonín Novotný, First Secretary of the KSČ and President of Czechoslovakia. In their place, a new generation of Slovak Communists took control of party and state organs in Slovakia, led by Alexander Dubček, who became First Secretary of the Slovak branch of the party.

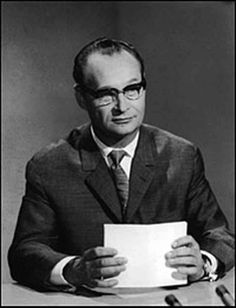

On the night of 20–21 August 1968, Warsaw Pact forces entered Czechoslovakia. The occupying armies quickly seized control of Prague and the Central Committee's building, taking Dubček and other reformers into Soviet custody. But, before they were arrested, Dubček urged the people not to resist militarily, on the grounds that “presenting a military defence would have meant exposing the Czech and Slovak peoples to a senseless bloodbath”. Later in the day, Dubček and the others were taken to Moscow on a Soviet military transport aircraft (reportedly one of the aircraft used in the Soviet invasion).

Dubček was forced to resign as First Secretary in April 1969, following the Czechoslovak Hockey Riots. He was re-elected to the Federal Assembly (as the federal parliament was now called) and became its Speaker. He was later sent as ambassador to Turkey (1969–70), allegedly in the hope that he would defect to the West, which however did not occur. In 1970, he was expelled from the Communist party and lost his seats in the Slovak parliament (which he had held continuously since 1964) and the Federal Assembly.

After his expulsion from the party, Dubček worked in the Forestry Service in Slovakia. He remained a popular figure among the Slovaks and Czechs he encountered on the job, using this reverence to procure scarce and hard-to-find materials for his workplace. Dubček and his wife, Anna, continued to live in a comfortable villa in a nice neighbourhood in Bratislava. In 1988, Dubček was allowed to travel to Italy to accept an honorary doctorate from Bologna University, and, while there, he gave an interview with Italian newspaper L'Unità, his first public remarks to the press since 1970. Dubček's appearance and interview helped to return him to international prominence.

Dubček was elected Chairman of the Federal Assembly (the Czechoslovak Parliament) on 28 December 1989, and re-elected in 1990 and 1992.

At the time of the overthrow of Communist party rule, Dubček described the Velvet Revolution as a victory for his humanistic socialist outlook. In 1990, he received the International Humanist Award from the International Humanist and Ethical Union. He also gave the commencement address to the graduates of the Class of 1990 at The American University in Washington, D.C.; it was his first trip to the United States.

Dubček died on 7 November 1992, as a result of injuries sustained in a car crash that took place on 1 September on the Czech D1 highway, near Humpolec. He was buried in Slávičie údolie cemetery in Bratislava, Slovakia.

The period following Novotný's downfall became known as the Prague Spring. During this time, Dubček and other reformers sought to liberalize the Communist government—creating "socialism with a human face". Though this loosened the party's influence on the country, Dubček remained a devoted Communist and intended to preserve the party's rule. However, during the Prague Spring, he and other reform-minded Communists sought to win popular support for the Communist government by eliminating its worst, most repressive features, allowing greater freedom of expression and tolerating political and social organizations not under Communist control. "Dubček! Svoboda!" became the popular refrain of student demonstrations during this period, while a poll gave him 78% public support. Yet Dubček found himself in an increasingly untenable position. The program of reform gained momentum, leading to pressures for further liberalization and democratization. At the same time, hard-line Communists in Czechoslovakia and the Leaders of other Warsaw Pact countries pressured Dubček to rein in the Prague Spring. Though Dubček wanted to oversee the reform movement, he refused to resort to any draconian measures to do so, while still stressing the leading role of the Party and the centrality of the Warsaw Pact.