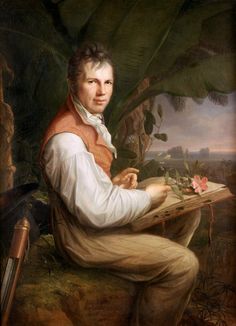

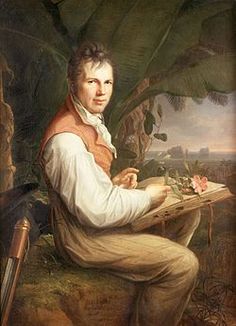

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Geographer |

| Birth Day | September 14, 1769 |

| Birth Place | Berlin, German |

| Age | 250 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 6 May 1859(1859-05-06) (aged 89)\nBerlin, Kingdom of Prussia, German Confederation |

| Birth Sign | Libra |

| Resting place | Schloss Tegel |

| Alma mater | Freiberg School of Mines (diploma, 1792) University of Frankfurt (Oder) (no degree) University of Göttingen (no degree) University of Berlin (no degree) |

| Known for | Biogeography, Kosmos (1845–1862), Humboldt Current, Humboldtian science, Berlin Romanticism |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1852) |

| Fields | Geography |

| Academic advisors | Markus Herz, Carl Ludwig Willdenow |

| Notable students | Louis Agassiz |

| Influences | F. W. J. Schelling |

| Influenced | Darwin, Wallace, Thoreau, Whitman, Emerson, Muir, Irving |

Net worth

Alexander von Humboldt, renowned for his contributions as a geographer, is anticipated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M by the year 2024. Widely recognized as one of the greatest scientists of his time, Alexander von Humboldt made significant advancements in various fields of study, including geography, botany, and geology. His extensive explorations and remarkable scientific work earned him both fame and fortune during his lifetime, leading to the estimation of his substantial net worth. As a notable figure in history, his achievements continue to be celebrated, and his legacy resonates in the field of geography to this day.

Biography/Timeline

In Madrid, Humboldt sought authorization to travel to Spain's realms in the Americas; he was aided in obtaining it by the German representative of Saxony at the royal Bourbon court. Baron Forell had an interest in mineralogy and science endeavors and inclined to help Humboldt. Humboldt's timing could not have been better to interest the Spanish crown in an extended scientific expedition to their possessions in the New World. With the accession of the House of Bourbon to the Spanish throne following the death of the last Hapsburg king, Charles II (died 1700), and the War of the Spanish Succession, which the House of Bourbon won, the Spanish Bourbons embarked on a program of reform in Spain and then Spanish America. The Bourbon Reforms sought to reform administration of the realms and revitalize their economies. At the same time as the Bourbon reforms, the Spanish Enlightenment was in florescence. For Humboldt, "the confluent effect of the Bourbon revolution in government and the Spanish Enlightenment had created ideal conditions for his venture."

Humboldt's father, Alexander Georg von Humboldt, belonged to a prominent Pomeranian family, although not one of the titled gentry; a major in the Prussian Army, who had served with the Duke of Brunswick. At age 42, Alexander Georg was rewarded for his services in the Seven Years' War with the post of Royal Chamberlain. He profited from the contract to lease state lotteries and tobacco sales. He first married the daughter of Prussian General Adjutant Schweder. In 1766, Alexander Georg married Maria Elisabeth Colomb, a well-educated woman and widow of Baron Hollwede, with whom she had a son. Alexander Georg and Maria Elisabeth had three children, a daughter, who died young, and then two sons, Wilhelm and Alexander. Her first-born son, Wilhelm's and Alexander's half-brother, was something of a ne'er do well, not often mentioned in the family history.

Alexander von Humboldt was born in Berlin in Prussia on 14 September 1769. He was baptized as a baby in the Lutheran faith, with the Duke of Brunswick serving as godfather.

As a student he became infatuated with Wilhelm Gabriel Wegener, a theology student, penning a succession of letters expressing his "fervent love". At 25 he met Reinhardt von Haeften (19 May 1772 – 20 October 1803), a 21-year-old lieutenant, with whom he lived and travelled for two years, and to whom he wrote in 1794: "I only live through you, my good precious Reinhardt." When von Haeften became engaged, Humboldt begged to remain living with him and his wife: "Even if you must refuse me, treat me coldly with disdain, I should still want to be with you...the love I have for you is not just friendship or brotherly love, it is veneration."

Venezuela from the sixteenth century to the eighteenth was a relative backwater compared to the seats of the Spanish viceroyalties based in New Spain (Mexico) and Peru, but during the Bourbon reforms, the northern portion of Spanish South America was reorganized administratively, with the 1777 establishment of a Captaincy-General based at Caracas. A great deal of information on the new jurisdiction had already been compiled by François de Pons and published in 1806. Rather than describe the administrative center of Caracas, Humboldt started his researches with the valley of Aragua where export crops of sugar, coffee, cacao, and cotton were cultivated. Cacao plantations were the most profitable as world demand for chocolate rose.

Alexander Georg died in 1779, leaving the brothers Humboldt in the care of their emotionally distant mother. She did have high ambitions for Alexander and his older brother Wilhelm, hiring excellent tutors, who were Enlightenment thinkers, including Kantian physician Marcus Herz and Botanist Karl Ludwig Willdenow, who became one of the most important botanists in Germany. Humboldt's mother expected them to become civil servants of the Prussian state. The money Baron Holwede left to Alexander's mother became, after her death, instrumental in funding Alexander's explorations, contributing more than 70% of his private income.

Due to his youthful penchant for collecting and labeling plants, shells and insects, Alexander received the playful title of "the little apothecary". Marked for a political career, Alexander studied Finance for six months in 1787 at the University of Frankfurt (Oder), which his mother might have chosen less for its academic excellence as its closeness to their home in Berlin. On 25 April 1789 he matriculated at Göttingen, then known for the lectures of C. G. Heyne and Anatomist J. F. Blumenbach. His brother Wilhelm was already a student at Göttingen, but they did not interact much since their intellectual interests were quite different. His vast and varied interests were by this time fully developed.

Humboldt's scientific excursion up the Rhine resulted in his 1790 treatise Mineralogische Beobachtungen über einige Basalte am Rhein (Brunswick, 1790) (Mineralogic Observations on Several Basalts on the River Rhine).

Humboldt's passion for travel was of long standing. Humboldt's talents were devoted to the purpose of preparing himself as a scientific Explorer. With this emphasis, he studied commerce and foreign languages at Hamburg, geology at Technische Universität Bergakademie Freiberg in 1791 under A.G. Werner, leader of the Neptunist school of geology; from anatomy at Jena under J.C. Loder; and astronomy and the use of scientific instruments under F.X. von Zach and J.G. Köhler. At Freiberg, he met a number of men who were to prove important to him in his later career, including Spaniard Manuel del Rio, who became Director of the School of Mines the crown established in Mexico; Christian Leopold von Buch, who became a regional geologist; and, most importantly, Karl Freiesleben, who became Humboldt's tutor and close friend. During this period, his brother Wilhelm married, but Alexander did not attend the nuptials.

In 1792 and 1797 Humboldt was in Vienna; in 1795 he made a geological and botanical tour through Switzerland and Italy. Although this Service to the state was regarded by him as only an apprenticeship to the Service of science, he fulfilled its duties with such conspicuous ability that not only did he rise rapidly to the highest post in his department, but he was also entrusted with several important diplomatic missions.

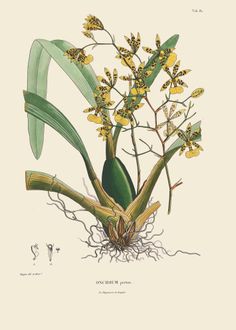

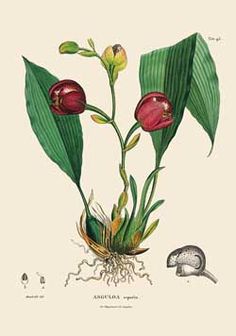

Humboldt's researches into the vegetation of the mines of Freiberg led to the publication in Latin (1793) of his Florae Fribergensis, accedunt Aphorismi ex Doctrina, Physiologiae Chemicae Plantarum, which was a compendium of his botantical researches. That publication brought him to the attention of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who had met Humboldt at the family home when Alexander was a boy, but Goethe was now interested in meeting the young scientist in order to discuss metamorphism of plants. An introduction was arranged by Humboldt's brother who lived in the university town of Jena, not far from Goethe. Goethe had developed his own extensive theories on comparative anatomy. Working before Darwin, he believed that animals had an internal force, an urform, that gave them a basic shape and then they were further adapted to their environment by an external force. Humboldt urged him to publish his theories. Together the two discussed and expanded these ideas. Goethe and Humboldt soon became close friends.

In 1794 Humboldt was admitted to the famous group of intellectuals and cultural Leaders of Weimar Classicism. Goethe and Schiller were the key figures at the time. Humboldt contributed (7 June 1795) to Schiller's new periodical, Die Horen, a philosophical allegory entitled Die Lebenskraft, oder der rhodische Genius.

The death of his stern mother, on 19 November 1796 after a year's suffering with cancer, set him free. Neither brother attended the funeral. Humboldt had not hidden his aversion to his mother, with one correspondent writing him after her death, "her death...must be particularly welcomed by you." After severing his official connections, he awaited an opportunity to fulfill his long-cherished dream of travel.

Humboldt was able to spend more time on writing up his research. He had used his own body for experimentation on muscular irritability, recently discovered by Luigi Galvani and published his results, Versuche über die gereizte Muskel- und Nervenfaser (Berlin, 1797) (Experiments on Stimulated Muscle and Nerve Fibres), enriched in the French translation with notes by Blumenbach.

Alexander von Humboldt published prolifically throughout his life. Many works were published originally in French or German, then translated to other languages, sometimes with competing translation editions. Humboldt himself did not keep track of all the various editions. He wrote specialized works on particular topics of botany, zoology, astronomy, mineralogy, among others, but he also wrote general works that attracted a wide readership, especially his Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent during the years 1799-1804 His Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain was widely read in Mexico itself, the United States, as well as in Europe.

On 24 November 1800, the two friends set sail for Cuba, landing on 19 December, where they met fellow Botanist and plant collector John Fraser. Fraser and his son had been shipwrecked off the Cuban coast, and did not have a license to be in the Spanish Indies. Humboldt, who was already in Cuba, interceded with crown officials in Havana, as well as giving them money and clothing. Fraser obtained permission to remain in Cuba and explore. Humboldt entrusted Fraser with taking two cases of Humboldt and Bonpland's botanical specimens to England when he returned, for eventual conveyance to the German botantist Willdenow in Berlin. Humboldt and Bonpland stayed in Cuba until 5 March 1801, when they left for the mainland of northern South America again, arriving there on 30 March.

After their first stay in Cuba of three months they returned the mainland at Cartagena de Indias (now in Colombia), a major center of trade in northern South America. Ascending the swollen stream of the Magdalena River to Honda and arrived in Bogotá on 6 July 1801 where they met the Spanish Botanist José Celestino Mutis, head of the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Granada, staying there until 8 September 1801. Mutis was generous with his time and gave Humboldt access to the huge pictorial record he had compiled since 1783. Mutis was based in Bogotá, but as with other Spanish expeditions, he had access to local knowledge and a workshop of artists, who created highly accurate and detailed images. This type of careful recording meant that even if specimens were not available to study at a distance, "because the images traveled, the botanists did not have to." Humboldt was astounded at Mutis's accomplishment; when Humboldt published his first volume on botany, he dedicated it to Mutis, "as a simply mark of our admiration and acknowledgement."

A travelling companion in the Americas for five years was Aimé Bonpland, and in Quito in 1802 he met the Ecuadorian aristocrat Don Carlos Montúfar, who travelled with Humboldt to Europe and lived with him. In France, Humboldt travelled and lived with the Physicist and balloonist Joseph Louis Gay Lussac. Later he had a deep friendship with the married French Astronomer François Ara Go, whom he met daily for 15 years.

Humboldt and Bonpland had not intended to go to New Spain, but when they were unable to join a voyage to the Pacific, they left the Ecuadorian port of Guayaquil and headed for Acapulco on Mexico's west coast, landing there on 15 February 1803. Even before Humboldt and Bonpland started on their way to New Spain's capital on Mexico's central plateau, Humboldt realized the captain of the vessel that brought them to Acapulco had reckoned its location incorrectly. Since Acapulco was the main west coast port and the terminus of the Asian trade from the Spanish Philippines, having accurate maps of its location was extremely important. Humboldt set up his instruments, surveying the deep water bay of Acapulco, to determine its longitude.

His discovery of the decrease in intensity of Earth's magnetic field from the poles to the equator was communicated to the Paris Institute in a memoir read by him on 7 December 1804. Its importance was attested by the speedy emergence of rival claims.

During his lifetime Humboldt became one of the most famous men in Europe. Academies, both native and foreign, were eager to elect him to their membership, the first being The American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, which he visited at the tail end of his travel through the Americas. He was elected to the Prussian Academy of Sciences in 1805. Over the years other learned societies in the U.S. elected him a member, including the American Antiquarian Society (Worcester, MA) in 1816; the New York Historical Society in 1820; a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1822.; the American Ethnological Society (New York) in 1843; and the American Geographical and Statistical Society, (New York) in 1856. He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1810. The Royal Society, whose President Sir Joseph Banks had aided Humboldt as a young man, now welcomed him as a foreign member.

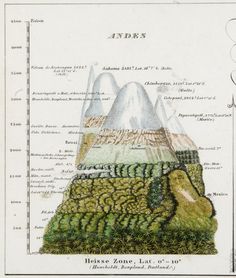

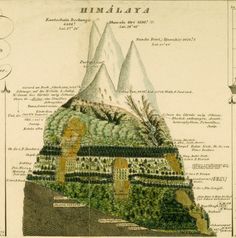

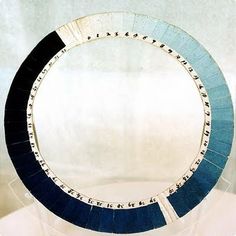

His Essay on the Geography of Plants (published first in French and then German, both in 1807) was based on the then novel idea of studying the distribution of organic life as affected by varying physical conditions. This was most famously depicted in his published cross-section of Chimborazo, approximately two feet by three feet (54 cm x 84 cm) color pictorial, he called Ein Naturgemälde der Anden and what is also called the Chimborazo Map. It was a fold-out at the back of the publication. Humboldt first sketched the map when he was in South America, which included written descriptions on either side of the cross-section of Chimborazo. These detailed the information on temperature, altitude, humidity, atmosphere pressure, and the animal and plants (with their scientific names) found at each elevation. Plants from the same genus appear at different elevations. The depiction is on an east-west axis going from the Pacific coast lowlands to the Andean range of which Chimborazo was a part, and the eastern Amazonian basin. Humboldt showed the three zones of coast, mountains, and Amazonia, based on his own observations, but he also drew on existing Spanish sources, particularly Pedro Cieza de León, which he explicitly referred to. The Spanish American scientist Francisco José de Caldas had also measured and observed mountain environments and had earlier come to similar ideas about environmental factors in the distribution of life forms. Humboldt was thus not putting forward something entirely new, but it is argued that his finding is not derivative either. The Chimborazo map displayed complex information in an accessible fashion. The map was the basis for comparison with other major peaks. "The Naturgemälde showed for the first time that nature was a global force with corresponding climate zones across continents." Another assessment of the map is that it "marked the beginning of a new era of environmental science, not only of mountain ecology but also of global-scale biogeophysical patterns and processes."

The editing and publication of the encyclopedic mass of scientific, political and archaeological material that had been collected by him during his absence from Europe was now Humboldt's most urgent Desire. After a short trip to Italy with Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac for the purpose of investigating the law of magnetic declination and a stay of two and a half years in Berlin, in the spring of 1808, he settled in Paris. His purpose for being located there was to secure the scientific cooperation required for bringing his great work through the press. This colossal task, which he at first hoped would occupy but two years, eventually cost him twenty-one, and even then it remained incomplete.

After arriving in Washington D.C, Humboldt held numerous intense discussions with Jefferson on both scientific matters and also his year-long stay in New Spain. Jefferson had only recently concluded the Louisiana Purchase, which now placed New Spain on the southwest border of the United States. The Spanish minister in Washington, D.C. had declined to furnish the U.S. government with information about Spanish territories, and access to the territories was strictly controlled. Humboldt was able to supply Jefferson with the latest information on the population, trade agriculture and military of New Spain. This information would later be the basis for his Essay on the Political Kingdom of New Spain (1810). Jefferson was unsure of where the border of the newly-purchased Louisiana was precisely, and Humboldt wrote him a two-page report on the matter. Jefferson would later refer to Humboldt as "the most scientific man of the age". Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the treasury said of Humboldt, "I was delighted and swallowed more information of various kinds in less than two hours than I had for two years past in all I had read or heard." Gallatin, in turn, supplied Humboldt with information he sought on the United States.

In 1811, and again in 1818, projects of Asiatic exploration were proposed to Humboldt, first by Czar Nicolas I's Russian government, and afterwards by the Prussian government; but on each occasion, untoward circumstances interposed. It was not until he had begun his sixtieth year that he resumed his early role of traveler in the interests of science.

In 1814 Humboldt accompanied the allied sovereigns to London. Three years later he was summoned by the king of Prussia to attend him at the congress of Aachen. Again in the autumn of 1822 he accompanied the same monarch to the Congress of Verona, proceeded thence with the royal party to Rome and Naples and returned to Paris in the spring of 1823. Humboldt had long regarded Paris as his true home. Thus, when at last he received from his sovereign a summons to join his court at Berlin, he obeyed reluctantly.

By his delineation (in 1817) of isothermal lines, he at once suggested the idea and devised the means of comparing the climatic conditions of various countries. He first investigated the rate of decrease in mean temperature with the increase in elevation above sea level, and afforded, by his inquiries regarding the origin of tropical storms, the earliest clue to the detection of the more complicated law governing atmospheric disturbances in higher latitudes. This was a major contribution to climatology.

During Humboldt's time in Paris, he met in 1818 the young and brilliant Peruvian student of the Royal Mining School of Paris, Mariano Eduardo de Rivero y Ustariz. Subsequently, Humboldt acted as a mentor of the career of this promising Peruvian scientist. Another recipient of Humboldt's aid was Louis Agassiz (1807–1873), who was directly aided with needed cash from Humboldt, assistance in securing an academic position, and help with getting his research on zoology published. Agassiz sent him copies of his publications and went on to gain considerable scientific recognition as a professor at Harvard. Agassiz delivered an address to the Boston Society of Natural History in 1869, on the centenary of his patron's birth. When Humboldt was an elderly man, he aided another young scholar, Gotthold Eisenstein, a brilliant, young, Jewish Mathematician in Berlin, for whom he obtained a small crown pension and whom he nominated for the Academy of Science.

At Göttingen he met Georg Forster, a naturalist who had been with Captain James Cook on his second voyage. Humboldt traveled with Forster in Europe. The two traveled to England, Humboldt's first sea voyage, The Netherlands, and France. In England, he met Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, who had traveled with Captain Cook; Banks showed Humboldt his huge herbarium, with specimens of the South Sea tropics. The scientific friendship between Banks and Humboldt lasted until Banks's death in 1820, and the two shared botanical specimens for study. Banks also mobilized his scientific contacts in later years to aid Humboldt's work.

After Mexican independence from Spain in 1821, the Mexican government recognized him with high honors for his services to the nation. In 1827, the first President of Mexico, Guadalupe Victoria granted Humboldt Mexican citizenship and in 1859, the President of Mexico, Benito Juárez, named Humboldt a hero of the nation (benemérito de la nación). The gestures were purely honorary; he never returned to the Americas following his expedition.

Kosmos was Humboldt's multi-volume effort in his later years to write a work bringing together all the research from his long career. The writing took shape in lectures he delivered before the University of Berlin in the winter of 1827–28. These lectures would form "the cartoon for the great fresco of the [K]osmos". His 1829 expedition to Russia supplied him with data comparative to his Latin American expedition.

For many years, it had been one of his favorite schemes to secure, by means of simultaneous observations at distant points, a thorough investigation of the nature and law of "magnetic storms" (a term invented by him to designate abnormal disturbances of Earth's magnetism). The meeting at Berlin, on 18 September 1828, of a newly formed scientific association, of which he was elected President, gave him the opportunity of setting on foot an extensive system of research in combination with his diligent personal observations. His appeal to the Russian government, in 1829, led to the establishment of a line of magnetic and meteorological stations across northern Asia. Meanwhile, his letter to the Duke of Sussex, then (April 1836) President of the Royal Society, secured for the undertaking, the wide basis of the British dominions.

Between May and November 1829 he and the growing expedition traversed the wide expanse of the Russian empire from the Neva to the Yenisei, accomplishing in twenty-five weeks a distance of 9,614 miles (15,472 km). Humboldt and the expedition party traveled by coach on well maintained roads, with rapid progress being made because of changes of horses at way stations. The party had grown, with Johann Seifert, who was a huntsman and collector of animal specimens; a Russian mining official; Count Adolphe Polier, one of Humboldt's friends from Paris; a cook; plus a contingent of Cossacks for security. Three carriages were filled with people, supplies, and scientific instruments. For Humboldt's magnetic readings to be accurate, they carried an iron-free tent. This expedition was unlike his Spanish American travels with Bonpland, with the two alone and sometimes accompanied by local guides.

Between 1830 and 1848 Humboldt was frequently employed in diplomatic missions to the court of King Louis Philippe of France, with whom he always maintained the most cordial personal relations. Charles X of France had been overthrown, with Louis-Philippe of the house of Orléans becoming king. Humboldt knew the family, and he was sent by the Prussian monarch to Paris to report on events to his monarch. He spent three years in France, from 1830 to 1833. His friends François Ara Go and Guillaume Guizot, who were appointed to posts in Louis-Philippe's government.

Humboldt was generous toward his friends and mentored young Scientists. He and Bonpland parted ways after their return to Europe, and Humboldt largely took on the task of publishing the results of their Latin American expedition at Humboldt's expense, but he included Bonpland as co-author on the nearly published 30 volumes. Bonpland returned to Latin America, settling in Buenos Aires, Argentina, then moved to the countryside near the border with Paraguay. The forces of Dr. José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia, the strong man of Paraguay, abducted Bonpland after killing Bonpland's estate workers. Bonpland was accused of "agricultural espionage" and of threatening Paraguay's virtual monopoly on the cultivation of yerba mate. Despite international pressure, including the British government and Simón Bolívar's, along with European Scientists including Humboldt, Francia kept Bonpland prisoner until 1831. He was released after nearly 10 years in Paraguay. Humboldt and Bonpland maintained a warm correspondence about science and politics until Bonpland's death in 1858.

Humboldt inherited a significant fortune, but the expense of his travels, and most especially of publishing (thirty volumes in all), had by 1834 made him totally reliant on the pension of King Frederick william III. Although he preferred living in Paris, by 1836 the King had insisted he return to Germany. He lived with the Court at Sanssouci, and latterly in Berlin, with his valet Seifert, who had accompanied him to Russia in 1829.

Humboldt's brother, Wilhelm, died on 8 April 1835. Alexander lamented that he had lost half of himself with the death of his brother. Upon the accession of the crown Prince Frederick william IV in June 1840, Humboldt's favor at court increased. Indeed, the new king's craving for Humboldt's company became at times so importunate as to leave him only a few waking hours to work on his writing.

Humboldt was a significant contributor to cartography, creating maps, particularly of New Spain, that became the template for later mapmakers in Mexico. His careful recording of latitude and longitude led to accurate maps of Mexico, the port of Acapulco, the port of Veracruz, and the Valley of Mexico, and a map showing trade patterns among continents. His maps also included schematic information on geography, converting areas of administrative districts (intendancies) using proportional squares. The U.S. was keen to see his maps and statistics on New Spain, since they had implication for territorial claims following the Louisiana Purchase. Later in life, Humboldt published three volumes (1836–39) examining sources that dealt with the early voyages to the Americas, pursuing his interest in nautical astronomy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. His research yielded the origin of the name "America", put on a map of the Americas by Martin Waldseemüller.

Humboldt would later reveal to Darwin in the 1840s that he had been a fan of Darwin's grandfather's poetry. Erasmus Darwin had published the poem "Loves of the Plants" in the early 1800s. Humboldt praised the poem for combing nature and imagination, a theme that permeated Humboldt's own work.

The first two volumes of the Kosmos were published between the years 1845 and 1847 were intended to comprise the entire work, but Humboldt published three more volumes, one of which was posthumous. Humboldt had long aimed to write a comprehensive work about geography and the natural sciences. The work attempted to unify the sciences then known in a Kantian framework. With inspiration from German Romanticism, Humboldt sought to create a compendium of the world's environment. He spent the last decade of his long life — as he called them, his "improbable" years — continuing this work. The third and fourth volumes were published in 1850–58; a fragment of a fifth appeared posthumously in 1862.

The other two translations were made by Elizabeth Juliana Leeves Sabine under the superintendence of her husband Col. Edward Sabine (4 volumes 1846–1858), and by Elise Otté (5 volumes 1849–1858, the only complete translation of the 4 German volumes). These three translations were also published in the United States. The numbering of the volumes differs between the German and the English editions. Volume 3 of the German edition corresponds to the volumes 3 and 4 of the English translation, as the German volume appeared in 2 parts in 1850 and 1851. Volume 5 of the German edition was not translated until 1981, again by a woman. Otté's translation benefited from a detailed table of contents, and an index for every volume; of the German edition only volumes 4 and 5 had (extremely short) tables of contents, and the index to the whole work only appeared with volume 5 in 1862. Less well known in Germany is the atlas belonging to the German edition of the Cosmos "Berghaus' Physikalischer Atlas", better known as the pirated version by Traugott Bromme under the title "Atlas zu Alexander von Humboldt's Kosmos" (Stuttgart 1861).

As with most of Humboldt's works, Kosmos was also translated into multiple languages in editions of uneven quality. It was very popular in Britain and America. In 1849 a German newspaper commented that in England two of the three different translations were made by women, "while in Germany most of the men do not understand it." The first translation by Augustin Pritchard — published anonymously by Mr. Baillière (volume I in 1845 and volume II in 1848) — suffered from being hurriedly made. In a letter Humboldt said of it: "It will damage my reputation. All the charm of my description is destroyed by an English sounding like Sanskrit."

George Catlin, most famous for his portraits of North American Indians and paintings of life among various North American tribes also traveled to South America, producing a number of paintings. He wrote to Humboldt in 1855, sending him his proposal for South American travels. Humboldt replied, thanking him and sending a memorandum helping guide his travels.

On 24 February 1857, Humboldt suffered a minor stroke, which passed without perceptible symptoms. It was not until the winter of 1858–1859 that his strength began to decline; on 6 May 1859, he died peacefully in Berlin, aged 89. His last words were reported to be "How glorious these sunbeams are! They seem to call Earth to the Heavens!" His remains were conveyed in state through the streets of Berlin, in a hearse drawn by six horses. Royal chamberlains led the cortège, each charged with carrying a pillow with Humboldt's medals and other decorations of honor. Humboldt's extended family, descendants of his brother Wilhelm, walked in the procession. Humboldt's coffin was received by the prince-regent at the door of the cathedral. He was interred at the family resting-place at Tegel, alongside his brother Wilhelm and sister-in-law Caroline.

The honours which had been showered on Humboldt during life continued after his death. More places and species are named after Humboldt than after any other human being. The first centenary of Humboldt's birth was celebrated on 14 September 1869, with great enthusiasm in both the New and Old Worlds. Numerous monuments were constructed in his honour, such as Humboldt Park in Chicago, planned that year and constructed shortly after the Chicago fire. Newly explored regions and species named after Humboldt, as discussed below, also stand as a measure of his wide fame and popularity.

Alexander von Humboldt is also a German ship named after the scientist originally built in 1906 by the German shipyard AG Weser at Bremen as Reserve Sonderburg. She was operated throughout the North and Baltic Seas until being retired in 1986. Subsequently, she was converted into a three masted barque by the German shipyard Motorwerke Bremerhaven and was re-launched in 1988 as Alexander von Humboldt.

In 1908, the sexual researcher Paul Näcke gathered reminiscences from homosexuals including Humboldt's friend the Botanist Karl Bolle, then 90 years old: some of the material was incorporated by Magnus Hirschfeld into his 1914 study Homosexuality in Men and Women. However, speculations about Humboldt's private life and possible homosexuality continue to remain a fractious issue amongst scholars, particularly as earlier biographers had portrayed him as "a largely asexual, Christ-like Humboldt figure...suitable as a national idol."

After his death, Humboldt's friends and colleagues created the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (Stiftung in German) to continue his generous support of young academics. Although the original endowment was lost in the German hyperinflation of the 1920s, and again as a result of World War II, the Foundation has been re-endowed by the German government to award young academics and distinguished senior academics from abroad. It plays an important role in attracting foreign researchers to work in Germany and enabling German researchers to work abroad for a period.

Humboldt visited the mission at Caripe and explored the Guácharo cavern, where he found the oilbird, which he was to make known to science as Steatornis caripensis. Also described the Guanoco asphalt lake as "The spring of the good priest" ("Quelle des guten Priesters"). Returning to Cumaná, Humboldt observed, on the night of 11–12 November, a remarkable meteor shower (the Leonids). He proceeded with Bonpland to Caracas where he climbed the Avila mount with the young poet Andrés Bello, the former tutor of Simón Bolívar, who later became the leader of independence in northern South America. Humboldt met the Venezuelan Bolívar himself in 1804 in Paris and spent time with him in Rome. The documentary record does not support the supposition that Humboldt inspired Bolívar to participate in the struggle for independence, but it does indicate Bolívar's admiration for Humboldt's production of new knowledge on Spanish America.

Humboldt remained distant of organized religion: he did not believe in the Bible as an inerrant document, nor in the divinity of Jesus; yet, Humboldt still held deep respect for the ideal side of religious belief and church life within human communities. He differentiated between "negative" religions, and those "all positive religions [which] consist of three distinct parts — a code of morals which is nearly the same in all of them, and generally very pure; a geological chimera, and a myth or a little historical novel." In Cosmos, he wrote about how rich geological descriptions were found in different religious traditions, and stated:"Christianity gradually diffused itself, and, wherever it was adopted as the religion of the state, it not only exercised a beneficial condition on the lower classes by inculcating the social freedom of mankind, but also expanded the views of men in their communion with Nature...this tendency to glorify the Deity in his works gave rise to a taste for natural observation."

The Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, observes, "Thus that scientific conspiracy of nations which is one of the noblest fruits of modern civilization was by his exertions first successfully organized". However, earlier examples of international scientific cooperation exist, notably the 18th-century observations of the transits of Venus.