Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Former Premier of the Soviet Union |

| Birth Year | 1904 |

| Birth Place | St. Petersburg, Russian Empire, Russian |

| Age | 116 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 18 December 1980(1980-12-18) (aged 76)\nMoscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Deputy | First Deputy Premiers Dmitriy Ustinov Kirill Mazurov Dmitry Polyansky Nikolai Tikhonov |

| Preceded by | Ivan Khokhlov |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Rodionov |

| Premier | Joseph Stalin |

| Citizenship | Soviet |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Spouse(s) | Klavdia Andreyevna (died 1967) |

| Residence | House on the Embankment |

| Profession | Teacher, civil servant |

| Allegiance | Russian SFSR |

| Service/branch | Red Army |

| Years of service | 1919–1921 |

| Rank | Conscript |

| Commands | Red Army |

| Battles/wars | Russian Civil War |

Net worth: $11 Million (2024)

Alexei Kosygin, the renowned Former Premier of the Soviet Union in Russian, is expected to have an estimated net worth of $11 million by 2024. As a prominent political figure, Kosygin has served in various high-ranking positions within the Soviet government, contributing significantly to the country's development. His leadership and economic policies have played a pivotal role in shaping the Soviet Union's history. Despite his tremendous contributions, Kosygin's wealth is relatively moderate compared to other figures in the global political arena. Nonetheless, his impact remains indelible, solidifying his position as a key figure in Russian and international politics.

Biography/Timeline

He was conscripted into a labour army on the Bolshevik side during the Russian Civil War. After the Red Army's demobilisation in 1921, Kosygin attended the Leningrad Co-operative Technical School and found work in the system of consumer co-operatives in Novosibirsk, Siberia. When asked why he worked in the co-operative sector of the economy, Kosygin replied, quoting a slogan of Vladimir Lenin: "Co-operation – the path to socialism!" Kosygin stayed there for six years.

Brezhnev was able to criticise Kosygin by contrasting him with Vladimir Lenin, whom Brezhnev claimed to have been more interested in improving the conditions of Soviet agriculture than improving the quality of light industrial goods. Kosygin's support for producing more consumer goods was also criticised by Brezhnev, and his supporters, most notably Konstantin Chernenko, for being a return to quasi First World policies. At the 23rd Party Congress Kosygin's position was weakened when Brezhnev's supporters were able to increase expenditure on defence and agriculture. However, Brezhnev did not have a majority in the Politburo, and could count on only four votes. In the Politburo Kosygin could count on Kiril Mazurov's vote, and when Kosygin and Podgorny were not bickering with each other, they actually had a majority in the Politburo over Brezhnev. Unfortunately for Kosygin this was not often the case, and Kosygin and Podgorny were constantly disagreeing on policy.

He applied for a membership in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1927 and returned to Leningrad in 1930 to study at the Leningrad Textile Institute; he graduated in 1935.

After finishing his studies, Kosygin was employed as a textile mill Director. Three years later, he was elected Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Leningrad City Soviets of Working People's Deputies by the Leningrad Communist Party, and the following year he was appointed People's Commissar for Textile and Industry and earned a seat on the Central Committee (CC). In 1940 Kosygin became a Deputy chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, and was appointed in 1943 as Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Russian SFSR.

Kosygin worked for the State Defence Committee during the Great Patriotic War (World War II). As Deputy Chairman of the Council of Evacuation, his task was to evacuate industry from territories soon to be overrun by the Germans. He broke the Leningrad Blockade by organising the construction of a supply route and a pipeline on the bottom of Lake Ladoga. Kosygin was a candidate member of the Politburo from 1946 to 1949, and became a full member toward the end of Joseph Stalin's rule; he lost his seat in 1952. He briefly served as Minister of Finance in 1948, and as Minister of Light Industry from 1949 to 1953.

Following Stalin's death in March 1953, Kosygin was demoted, but as a staunch ally of Khrushchev, his career soon turned around. While never one of Khrushchev's protégés, Kosygin quickly moved up the party ladder. Kosygin became an official of the State Planning Committee in 1957, and was made a candidate member of the Politburo. He was promoted to the State Planning Committee chairmanship, and became Khrushchev's First Deputy Premier in 1960. As First Deputy Premier Kosygin travelled abroad, mostly on trade missions, to countries such as North Korea, India, Argentina and Italy, for instance. Later, in the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kosygin was the Soviet spokesman for improved relations between the Soviet Union and the United States. Kosygin regained his old seat in the Politburo at the 22nd Party Congress in 1961.

Kosygin, along with Alexey Kuznetsov and Voznesensky, formed a Troika in the aftermath of the war, with all three being promoted up the Soviet hierarchy by high-standing officials such as Stalin. Kosygin's life, which was connected to Kuznetsov through marriage, was hanging by a thread. How or why Kosygin survived the show trials is unknown, but he, as some jokes say, "must have drawn a lucky lottery ticket". Nikita Khrushchev blamed Beria and Malenkov for the innocent deaths of Kuznetsov and Voznesensky, and accused Malenkov in 1957 of having concocted the plot so that either Malenkov or Beria would succeed Stalin upon his death.

After the power struggle triggered by Stalin's death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev became the new leader. On 20 March 1959, Kosygin was appointed to the position of Chairman of the State Planning Committee (Gosplan), a post he would hold for little more than a year. Kosygin next became First Deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers. When Khrushchev was replaced in 1964, Kosygin and Leonid Brezhnev became Premier and First Secretary respectively. Kosygin, along with Brezhnev and Nikolai Podgorny, the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, was a member of the newly established collective leadership. Kosygin became one of two major power players within the Soviet hierarchy, the other being Brezhnev, and was able to initiate the failed 1965 economic reform, usually referred to simply as the Kosygin reform. This reform, along with his more open stance on solving the Prague Spring (1968), made Kosygin one of the most liberal members of the top leadership.

With hostility towards reform growing, the poor results, and Kosygin's reformist stance, led to a popular backlash against him. Kosygin lost most of the privileges he had enjoyed before the reform, but Brezhnev was never able to remove him from the office of Chairman of the Council of Ministers, despite his weakened position. In the aftermath of his failed reform, Kosygin spent the rest of his life improving the economic administration through the modification of targets; he implemented various programmes to improve food security and ensure the Future intensification of production. There is no proof to back up the claim that the reform itself contributed to the high growth seen in the late-1960s, and that its cancellation had anything to do with the stagnating growth of the economy which began in the 1970s.

The removal of Khrushchev in 1964 signalled the end of his "housing revolution". Housing construction declined between 1960 and 1964 to an average of 1.63 million square metres. Following this sudden decrease, housing construction increased sharply between 1965 and 1966, but dropped again, and then steadily grew (the average annual growth rate was 4.26 million square metres). This came largely at the expense of businesses. While the housing shortage was never fully resolved, and still remains a Problem in present-day Russia, the reform overcame the negative trend and renewed the growth of housing construction.

Chernenko: The Last Bolshevik: The Soviet Union on the Eve of Perestroika author Ilya Zemtsov describes Kosygin as a "Determined and intelligent, an outstanding administrator" and claims he distinguished himself from the other members of the Soviet leadership with his "extraordinary capacity for work". Historians Moshe Lewin and Gregory Elliott, the authors of The Soviet Century, describes him as a "phenomenal administrator". "His strengths", David Law writes, was "his exceptional capability as an administrator". According to Law Kosygin proved himself to be a "competent politician" also. Historians Evan Mawdsley and Stephen White claim that Brezhnev was unable to remove Kosygin because his removal would mean the loss of his last "capable administrator". In their book, The Unknown Stalin, Roy Medvedev and Zhores Medvedev called Kosygin an "outstanding organiser", and the "new Voznesensky". Historian Archie Brown, the author The Rise & Fall of Communism, believes the 1965 Soviet economic reform to have been too "modest", and claimed that Kosygin "was too much a product of the Soviet ministerial system, as it evolved under Stalin, to become a radical economic reformer". However, Brown does believe that Kosygin was "an able administrator". Gvishiani, a Russian Historian, concluded that "Kosygin survived both Stalin and Khrushchev, but did not manage to survive Brezhnev."

The Eighth Five-Year Plan (1966–1970) is considered to be one of the most successful periods for the Soviet economy and the most successful when it comes to consumer production (see The "Kosygin" reform). The 23rd Party Congress and the Ninth Five-Year Plan (1971–1975) had been postponed by Brezhnev due to a power struggle within the Soviet leadership. At the 23rd Party Congress Kosygin promised that the Ninth Five-Year Plan would increase the supply of food, clothing and other household appliances up to 50 percent. The plan envisaged a massive increase in the Soviet standard of living, with Kosygin proclaiming a growth of 40 percent for the population's cash income in his speech to the congress.

Brezhnev's consolidation to power weakened Kosygin's influence and prestige within the Politburo. By the 1970s, when Kosygin's position was given one blow after another, he was frequently hospitalised and at several occasions Kiril Mazurov, the First Deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers, acted on his behalf during Kosygin's absence. Kosygin suffered his first heart attack in 1976. After this incident, it is said that Kosygin changed from having a vibrant personality to being tired and fed up; he, according to people close to him, seemed to have lost the will to continue his work. He twice filed a letter of resignation between 1976 and 1980, but was turned down on both occasions. During Kosygin's sick leave, Brezhnev appointed Nikolai Tikhonov to the post of First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers. Tikhonov, as with Brezhnev, was a conservative, and through his post as First Deputy chairman Tikhonov was able to reduce Kosygin to a standby role. At a Central Committee plenum in June 1980, the Soviet economic development plan was outlined by Tikhonov, not Kosygin. The powers of the Premier diminished to the point where Kosygin was forced to discuss all decisions made by the Council of Ministers with Brezhnev.

In 1972, Kosygin signed a Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the government of Iraq, building on strong Soviet ties to the Iraqi Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party and previous close relations with Iraqi leader Abd al-Karim Qasim.

Kosygin initiated another economic reform in 1973 with the intentions of weakening the central Ministries and giving more powers to the regional authorities in republican and local-levels. The reform's failure to meet Kosygin's goal led to its cancellation. However, the reform succeeded in creating associations, an organisation representing various enterprises. The last significant reform undertaken by the pre-perestroika leadership was initiated by Kosygin's fifth government in a joint decision of the Central Committee and the Council of Ministers. The "Improving planning and reinforcing the effects of the economic mechanism on raising the effectiveness in production and improving the quality of work", more commonly known as the 1979 reform. The reform, in contrast to the 1965 reform, was intended to increase the central government's economic involvement by enhancing the duties and responsibilities of the ministries. Due to Kosygin's resignation in 1980, and because of Nikolai Tikhonov's conservative approach to economics, very little of the reform was actually implemented.

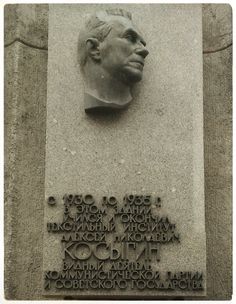

During his lifetime, Kosygin received seven Orders and two Awards from the Soviet state. He was awarded two Hero of Socialist Labour (USSR); one being on his 60th birthday by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet in 1964, on this occasion he was also awarded an Order of Lenin and a Hammer and Sickle Gold Medal. On 20 February 1974, to commemorate his 70th birthday, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet awarded him another Order of Lenin and his second Hammer and Sickle Gold Medal. In total, Kosygin was awarded six Orders of Lenin by the Soviet state, and one Order of the October Revolution and one Order of the Red Banner of Labour. During a state visit to Peru in the 1970s with Leonid Brezhnev and Andrei Gromyko, all three were awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of the Sun by President Francisco Morales Bermúdez. The Moscow State Textile University was named in his honour in 1981, in 1982 a bust to honour Kosygin was placed in Leningrad, present day Saint Petersburg. In 2006 the Russian Government renamed a street after him.

The Tenth Five-Year Plan (1976–1981) was referred to by Kosygin as the "plan of quality". Brezhnev rejected Kosygin's bid for producing more consumer goods during the Tenth Five-Year Plan. Because of it the total volume of consumer goods in industrial production only stood at 26 percent. Kosygin's son-in-law notes that Kosygin was furious with the decision, and proclaimed increased defence expenditure would become the Soviet Union's "complete ruin". The plan was less ambitious than its predecessors, with targets of national industrial growth no higher than what the rest of the world had already achieved. Soviet agriculture would receive a share investment of 34 percent, a share much larger than its proportional contribution to the Soviet economy, as it accounted for only 3 percent of Soviet GDP.

Brezhnev consolidated his own position over the Government Apparatus by strengthening Podgorny's position as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, literally head of state, by giving the office some of the functions of the Premier. The 1977 Soviet Constitution strengthened Podgorny's control of the Council of Ministers, by giving the post of head of state some executive powers. In fact, because of the 1977 Soviet Constitution, the Council of Ministers became subordinate to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. When Podgorny was replaced as head of state in 1977 by Brezhnev, Kosygin's role in day-to-day management of government activities was lessened drastically, through Brezhnev's new-found post. Rumours started circulating within the top circles, and on the streets, that Kosygin would retire due to bad health.

Kosygin was hospitalised in October 1980; during his stay Kosygin wrote a brief letter of resignation; the following day he was deprived of all government protection, communication, and luxury goods he had earned during his political life. Kosygin died on 18 December 1980; none of his Politburo colleagues, former aides, or security guards visited him. At the end of his life, Kosygin feared the complete failure of the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (1981–1985), claiming that the sitting leadership was reluctant to reform the stagnant Soviet economy. His funeral was postponed for three days, as Kosygin died on the eve of Brezhnev's birthday, and the day of Stalin's. He was buried in Red Square, Moscow. Kosygin was praised by Brezhnev as an individual who "labored selflessly for the good of the Soviet state". A state funeral was conducted and Kosygin was honoured by his peers; Brezhnev, Yuri Andropov, and Tikhonov laid an urn containing his ashes at the Kremlin Wall.

Kosygin was viewed with sympathy by the Soviet people, and is still presently viewed as an important figure in both Russian and Soviet history. Because of Kosygin's popularity among the Soviet people, Brezhnev developed a "strong jealousy" for Kosygin, according to Nikolai Egorychev. Mikhail Smirtyukov, the former Executive Officer of the Council of Ministers, recalled that Kosygin refused to go drinking with Brezhnev, a move which annoyed Brezhnev gravely. Nikolai Ryzhkov, the last Chairman of the Council of Ministers, in a speech to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union in 1987 referred to the "sad experiences of the 1965 reform", and claimed that everything went from bad to worse following the reform's cancellation.

The Sino–Soviet split chagrined Kosygin a great deal, and for a while he refused to accept its irrevocability; he briefly visited Beijing in 1969 due to increased tension between the USSR and China. Kosygin said, in a close-knit circle, that "We are communists and they are communists. It is hard to believe we will not be able to reach an agreement if we met face to face". His view on China changed however, and according to Harold Wilson, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Kosygin viewed China as a "organised military dictatorship" whose intended goal was to enslave "Vietnam and the whole of Asia".