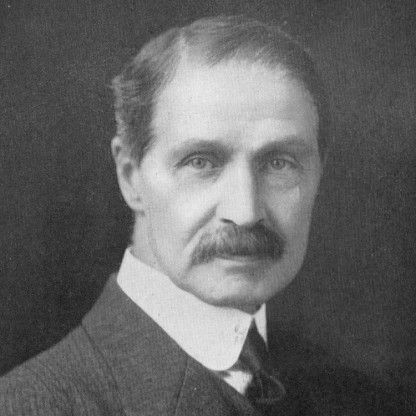

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Unknown Prime Minister |

| Birth Day | September 16, 1858 |

| Birth Place | Rexton, British |

| Age | 161 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 30 October 1923(1923-10-30) (aged 65)\nKensington, London, England, United Kingdom |

| Birth Sign | Libra |

| Monarch | George V |

| Preceded by | Andrew Dryburgh Provand |

| Succeeded by | George Nicoll Barnes |

| Prime Minister | Arthur Balfour |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Other political affiliations | Unionist |

| Spouse(s) | Annie Robley (m. 1891; her death 1909) |

| Children | James Isabel Charles Harrington Richard Catherine |

| Parents | James Law Eliza Kidston |

| Profession | Iron merchant |

Net worth

Andrew Bonar Law, also referred to as the Unknown Prime Minister in British history, is estimated to have a net worth ranging between $100K - $1M in 2024. Despite his relatively modest wealth, Bonar Law's political achievements and impact remain noteworthy. Serving as Prime Minister from 1922 until his resignation due to health issues in 1923, he played a significant role in stabilizing the Conservative Party and restoring Britain's economy after World War I. His leadership during this critical period has earned him a respected place in British political history, despite his comparatively lesser-known status.

Biography/Timeline

Many leading Conservatives (e.g. Birkenhead, Arthur Balfour, Austen Chamberlain, Robert Horne) were not members of the new Cabinet, which Birkenhead contemptuously referred to as "the Second Eleven". Although the Coalition Conservatives numbered no more than thirty, they hoped to dominate any Future Coalition government in the same way that the similarly sized Peelite group had dominated the Coalition Government of 1852–5 – an analogy much used at the time.

Law was born on 16 September 1858 in Kingston (now Rexton), New Brunswick, to Eliza Kidston Law and the Reverend James Law, a minister of the Free Church of Scotland with Scottish and Irish (mainly Ulster Scots) ancestry. From the perspective of the time, Law was not born in Canada, as New Brunswick was then a separate colony, and Canadian confederation did not occur until 1867.

James Law was the minister for several isolated townships, and had to travel between them by horse, boat and on foot. To supplement the family income, he bought a small farm on the Richibucto River, which Bonar helped tend along with his brothers Robert, william and John, and his sister Mary. Studying at the local village school, Law excelled at his studies, and it is here that he was first noted for his excellent memory. After Eliza Law died in 1861, her sister Janet travelled to New Brunswick from her home in Scotland to look after the Law children. When James Law remarried in 1870, his new wife took over Janet's duties, and Janet decided to return home to Scotland. She suggested that Bonar Law should come with her, as the Kidston family were wealthier and better connected than the Laws, and Bonar would have a more privileged upbringing. Both James and Bonar accepted this, and Bonar left with Janet, never to return to Kingston.

Law's chance to make his mark came with the issue of tariff reform. To cover the costs of the Second Boer War, Lord Salisbury's Chancellor of the Exchequer (Michael Hicks Beach) suggested introducing import taxes or tariffs on foreign metal, flour and grain coming into Britain. Such tariffs had previously existed in Britain, but the last of these had been abolished in the 1870s because of the free trade movement. A duty was now introduced on imported corn. The issue became "explosive", dividing the British political world, and continued even after Salisbury retired and was replaced as Prime Minister by his nephew, Arthur Balfour.

Law went to live at Janet's house in Helensburgh, near Glasgow. Her brothers Charles, Richard and william were partners in the family merchant bank Kidston & Sons, and as only one of them had married (and produced no heir) it was generally accepted that Law would inherit the firm, or at least play a role in its management when he was older. Immediately upon arriving from Kingston, Law began attending Gilbertfield School, a preparatory school in Hamilton. In 1873, aged fourteen, he transferred to the High School of Glasgow, where with his excellent memory he showed a talent for languages, excelling in Greek, German and French. During this period, he first began to play chess – he would carry a board on the train between Helensburgh and Glasgow, challenging other commuters to matches. He eventually became an excellent amateur player, and competed with internationally renowned chess masters. Despite his excellent academic record, it became obvious at Glasgow that he was better suited to Business than to university, and when he was sixteen, Law left school to become a clerk at Kidston & Sons.

At Kidston & Sons, Law received a nominal salary, on the understanding that he would gain a "commercial education" from working there that would serve him well as a businessman. In 1885 the Kidston brothers decided to retire, and agreed to merge the firm with the Clydesdale Bank.

By the time he was thirty Law had established himself as a successful businessman, and had time to devote to more leisurely pursuits. He remained an avid chess player, whom Andrew Harley called "a strong player, touching first-class amateur level, which he had attained by practice at the Glasgow Club in earlier days". Law also worked with the Parliamentary Debating Association and took up golf, tennis and walking. In 1888 he moved out of the Kidston household and set up his own home at Seabank, with his sister Mary (who had earlier come over from Canada) acting as the housekeeper.

In 1890, Law met Annie Pitcairn Robley, the 24-year-old daughter of a Glaswegian merchant, Harrington Robley. They quickly fell in love, and married on 24 March 1891. Little is known of Law's wife, as most of her letters have been lost. It is known that she was much liked in both Glasgow and London, and that her death in 1909 hit Law hard; despite his relatively young age and prosperous career, he never remarried. The couple had six children: James Kidston (1893–1917), Isabel Harrington (1895–1969), Charles John (1897–1917), Harrington (1899–1958), Richard Kidston (1901–1980), and Catherine Edith (1905–1992).

In 1897 Law was asked to become the Conservative Party candidate for the parliamentary seat of Glasgow Bridgeton. Soon after he was offered another seat, this one in Glasgow Blackfriars and Hutchesontown, which he took instead of Glasgow Bridgeton. Blackfriars was not a seat with high prospects attached; a working-class area, it had returned Liberal Party MPs since it was created in 1884, and the incumbent, Andrew Provand, was highly popular. Although the election was not due until 1902, the events of the Second Boer War forced the Conservative government to call a general election in 1900, later known as the khaki election. The campaign was unpleasant for both sides, with anti- and pro-war campaigners fighting vociferously, but Law distinguished himself with his oratory and wit. When the results came in on 4 October, Law was returned to Parliament with a majority of 1,000, overturning Provand's majority of 381. He immediately ended his active work at Jacks and Company (although he retained his directorship) and moved to London.

Law initially became frustrated with the slow speed of Parliament compared to the rapid pace of the Glasgow iron market, and Austen Chamberlain recalled him saying to Chamberlain that "it was very well for men who, like myself had been able to enter the House of Commons young to adapt to a Parliamentary career, but if he had known what the House of Commons was he would never had entered at this stage". He soon learnt to be patient, however, and on 18 February 1901 made his maiden speech. Replying to anti-Boer War MPs including David Lloyd George, Law used his excellent memory to quote sections of Hansard back to the opposition which contained their previous speeches supporting and commending the policies they now denounced. Although lasting only fifteen minutes and not a crowd- or press-pleaser like the maiden speeches of F.E. Smith or Winston Churchill, it attracted the attention of the Conservative Party Leaders.

As a result of Law's proven experience in Business matters and his skill as an economic spokesman for the government, Balfour offered him the position of Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade when he formed his government, which Law accepted, and he was formally appointed on 11 August 1902.

As Parliamentary Secretary his job was to assist the President of the Board of Trade, Gerald Balfour. At the time the tariff reform controversy was brewing, led by the Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, an ardent tariff reformer who "declared war" on free trade, and who persuaded the Cabinet that the Empire should be exempted from the new corn duty. After returning from a speaking tour of South Africa in 1903, Chamberlain found that the new Chancellor of the Exchequer (C.T. Ritchie) had instead abolished Hicks Beach's corn duty altogether in his budget. Angered by this, Chamberlain spoke at the Birmingham Town Hall on 15 May without the government's permission, arguing for an Empire-wide system of tariffs which would protect Imperial economies, forge the British Empire into one political entity and allow them to compete with other world powers.

In parliament, Law worked exceedingly hard at pushing for tariff reform, regularly speaking in the House of Commons and defeating legendary debaters such as Winston Churchill, Charles Dilke and Herbert Henry Asquith, former Home Secretary and later Prime Minister. His speeches at the time were known for their clarity and Common sense; Sir Ian Malcolm said that he made "the involved seem intelligible", and L.S. Amery said his arguments were "like the hammering of a skilled riveter, every blow hitting the nail on the head". Despite Law's efforts to forge consensus within the Conservatives, Balfour was unable to hold the two sides of his party together, and resigned as Prime Minister in December 1905, allowing the Liberals to form a government.

Campbell-Bannerman resigned as Prime Minister in April 1908 and was replaced by Herbert Henry Asquith. In 1909 he and his Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George introduced the People's Budget, which sought through increased direct and indirect taxes to redistribute wealth and fund social reform programmes. By parliamentary convention financial and budget bills are not challenged by the House of Lords, but in this case the predominantly Conservative Lords rejected the bill on 30 April, setting off a constitutional crisis.

The party was struck a blow in July 1906, when two days after a celebration of his seventieth birthday, Joseph Chamberlain suffered a stroke and was forced to retire from public life. He was succeeded as leader of the tariff reformers by his son Austen Chamberlain, who despite previous experience as Chancellor of the Exchequer and enthusiasm for tariff reform was not as skilled a speaker as Law. As a result, Law joined Balfour's Shadow Cabinet as the principal spokesman for tariff reform. The death of Law's wife on 31 October 1909 led him to work even harder, treating his political career not only as a job but as a coping strategy for his loneliness.

The January and December elections in 1910 destroyed the large Liberal majority, meaning they relied on the Irish Nationalists to maintain a government. As a result, they were forced to consider Home Rule, and with the passing of the Parliament Act 1911 which replaced the Lords' veto with a two-year power of delay on most issues, the Conservative Party became aware that unless they could dissolve Parliament or sabotage the Home Rule Bill, introduced in 1912, it would most likely become law by 1914.

By 12 March he had established that, should the Home Rule Bill be passed under the Parliament Act 1911, the Army (Annual) Act should be amended in the Lords to stipulate that the Army could not "be used in Ulster to prevent or interfere with any step which may thereafter be taken in Ulster to organise resistance to the enforcement of the Home Rule Act in Ulster nor to suppress any such resistance until and unless the present Parliament has been dissolved and a period of three months shall have lapsed after the meeting of a new Parliament". The Shadow Cabinet consulted legal experts, who agreed wholeheartedly with Law's suggestion. Although several members expressed dissent, the Shadow Cabinet decided "provisionally to agree to amendment of army act. but to leave details and decisions as to the moment of acting to Lansdowne and Law". In the end no amendment to the Army Act was offered, though; many backbenchers and party loyalists became agitated by the scheme and wrote to him that it was unacceptable – Ian Malcolm, a fanatical Ulster supporter, told Law that amending the Army Act would drive him out of the Party.

Lord Selborne had written to Law in 1912 to point out that vetoing or significantly amending the Act in the House of Lords would force the government to resign, and such a course of action was also suggested by others in 1913–14. Law believed that subjecting Ulstermen to a Dublin-based government they did not recognise was itself constitutionally damaging, and that amending the Army (Annual) Act to prevent the use of force in Ulster (he never suggested vetoing it) would not violate the constitution any more than the actions the government had already undertaken.

If Unionists wished to win the ensuing election they would have to show they were willing to compromise. In the end the amendment failed, but with the Liberal majority reduced by 40, and when a compromise amendment was proposed by another Liberal MP the government Whips were forced to trawl for votes. Law saw this as a victory, as it highlighted the split in the government. Edward Carson tabled another amendment on 1 January 1913 which would exclude all nine Ulster counties, more to test government resolve than anything else. While it failed, it allowed the Unionists to portray themselves as the party of compromise and the Liberals as stubborn and recalcitrant.

The Conservatives soon began to get annoyed that they were unable to criticise the Government, and took this into Parliament; rather than criticising policy, they would attack individual ministers, including the Lord Chancellor (who they considered "far too enamoured of German culture") and the Home Secretary, who was "too tender to aliens". By Christmas 1914 they were anxious about the war; it was not, in their opinion, going well, and yet they were restricted to serving on committees and making recruitment speeches. At about the same time, Law and David Lloyd George met to discuss the possibility of a coalition government. Law was supportive of the idea in some ways, seeing it as a probability that "a coalition government would come in time".

Law entered the coalition government as Colonial Secretary in May 1915, his first Cabinet post, and, following the resignation of Prime Minister and Liberal Party leader Asquith in December 1916, was invited by King George V to form a government, but he deferred to Lloyd George, Secretary of State for War and former Minister of Munitions, who he believed was better placed to lead a coalition ministry. He served in Lloyd George's War Cabinet, first as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons.

The second son, Charlie, who was a lieutenant in the King's Own Scottish Borderers, was killed at the Second Battle of Gaza in April 1917. The eldest son, James, who was a captain in the Royal Fusiliers, was shot down and killed on 21 September 1917, and the deaths made Law even more melancholy and depressed than before. The youngest son, Richard, later served as a Conservative MP and minister. Isabel married Sir Frederick Sykes (in the early years of World War I she had been engaged for a time to the Australian war correspondent Keith Murdoch) and Catherine married, firstly, Kent Colwell and, much later, in 1961, The 1st Baron Archibald.

While Chancellor, he raised the stamp duty on cheques from one penny to twopence in 1918. His promotion reflected the great mutual trust between the two Leaders and made for a well co-ordinated political partnership; their coalition was re-elected by a landslide following the Armistice. Law's two eldest sons were both killed whilst fighting in the war. In the 1918 General Election, Law returned to Glasgow and was elected as member for Glasgow Central.

By 1921–2 the coalition had become embroiled in an air of moral and financial corruption (e.g. the sale of honours). Besides the recent Irish Treaty and Edwin Montagu's moves towards greater self-government for India, both of which dismayed rank-and-file Conservative opinion, the government's willingness to intervene against the Bolshevik regime in Russia also seemed out of step with the new and more pacifist mood. A sharp slump in 1921 and a wave of strikes in the coal and railway industries also added to the government's unpopularity, as did the apparent failure of the Genoa Conference, which ended in an apparent rapprochement between Germany and Soviet Russia. In other words, it was no longer the case that Lloyd George was an electoral asset to the Conservative Party.

At a meeting at the Carlton Club, Conservative backbenchers, led by the President of the Board of Trade Stanley Baldwin and influenced by the recent Newport by-election which was won from the Liberals by a Conservative, voted to end the Lloyd George Coalition and fight the next election as an independent party. Austen Chamberlain resigned as Party Leader, Lloyd George resigned as Prime Minister and Law returned on 23 October 1922 in both jobs.

Law was soon diagnosed with terminal throat cancer and, no longer physically able to speak in Parliament, resigned on 22 May 1923. George V sent for Baldwin, whom Law is rumoured to have favoured over Lord Curzon. However Law did not offer any advice to the King. Law died later that same year in London at the age of 65. His funeral was held at Westminster Abbey where later his ashes were interred. His estate was probated at £35,736 (approximately £1,900,000 as of 2018).

Over the next few days the Conservative backbenchers threatened to break the truce and mount an attack on the government over the munitions situation. Law forced them to back down on 12 May, but on the 14th an article appeared in The Times blaming the British failure at the Battle of Aubers Ridge on the lack of munitions. This again stirred up the backbenchers, who were only just kept in line. The Shadow Cabinet took a similar line; things could not go on as they were. The crisis was only halted with the resignation of Lord Fisher. Fisher had opposed Winston Churchill over the Gallipoli Campaign, and felt that he could not continue in government if the two would be in conflict. Law knew that this would push the Conservative back bench over the edge, and met with David Lloyd George on 17 May to discuss Fisher's resignation. Lloyd George eventually agreed that "the only way to preserve a united front was to arrange for more complete cooperation between parties in the direction of the War".

Asquith and Law met for a second private meeting on 6 November, at which Asquith raised three possibilities. The first, suggested by Sir Edward Grey, consisted of "Home Rule within Home Rule" – Home Rule covering Ulster, but with partial autonomy for Ulster. The second was that Ulster would be excluded from Home Rule for a number of years before becoming part of it, and the third was that Ulster would be excluded from Home Rule for as long as it liked, with the opportunity of joining when it wished. Law made it clear to Asquith that the first two options were unacceptable, but the third might be accepted in some circles.