Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Composer |

| Birth Day | September 18, 2004 |

| Birth Place | Ansfelden, Austrian |

| Age | 16 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | October 11, 1896 |

| Birth Sign | Libra |

Net worth: $700,000 (2024)

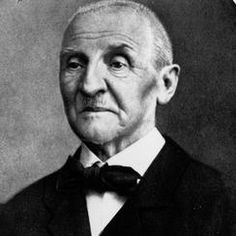

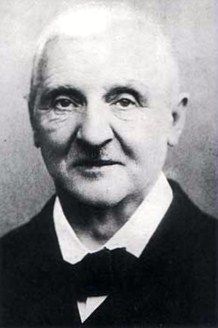

Anton Bruckner, renowned Austrian composer, is estimated to have a net worth of $700,000 by the year 2024. Bruckner, known for his masterful compositions and unique symphonies, has left a lasting impact on the world of classical music. Born in 1824, Bruckner dedicated his life to his craft, creating profound and harmonically complex works that continue to be celebrated today. His compositions, often characterized by soaring melodies and grand orchestration, have solidified his place in the pantheon of classical music. Bruckner's net worth is a testament to his talent and the enduring influence of his music.

Famous Quotes:

alone succeeded in creating a new school of symphonic writing.... Some have classified him as a conservative, some as a radical. Really he was neither, or alternatively was a fusion of both.... [H]is music, though Wagnerian in its orchestration and in its huge rising and falling periods, patently has its roots in older styles. Bruckner took Beethoven's Ninth Symphony as his starting-point.... The introduction to the first movement, beginning mysteriously and climbing slowly with fragments of the first theme to the gigantic full statement of that theme, was taken over by Bruckner; so was the awe-inspiring coda of the first movement. The scherzo and slow movement, with their alternation of melodies, are models for Bruckner's spacious middle movements, while the finale with a grand culminating hymn is a feature of almost every Bruckner symphony.

Biography/Timeline

Anton Bruckner was born in Ansfelden (then a village, now a suburb of Linz) on 4 September 1824. The ancestors of Bruckner's family were farmers and craftsmen; their history can be traced to as far back as the 16th century. They lived near a bridge south of Sindelburg, which led to their being called "Pruckhner an der Pruckhen" (bridgers on the bridge). Bruckner's grandfather was appointed schoolmaster in Ansfelden in 1776; this position was inherited by Bruckner's father, Anton Bruckner senior, in 1823. It was a poorly paid but well-respected position in the rural environment. Music was a part of the school curriculum, and Bruckner's father was his first music Teacher. Bruckner learned to play the organ early as a child. He entered school when he was six, proved to be a hard-working student, and was promoted to upper class early. While studying, Bruckner also helped his father in teaching the other children. After Bruckner received his confirmation in 1833, Bruckner's father sent him to another school in Hörsching. The schoolmaster, Johann Baptist Weiß, was a music enthusiast and respected organist. Here, Bruckner completed his school education and learned to play the organ excellently. Around 1835 Bruckner wrote his first composition, a Pange lingua – one of the compositions which he revised at the end of his life. When his father became ill, Anton returned to Ansfelden to help him in his work.

Bruckner was a renowned organist at the St Florian's Priory, where he improvised frequently. Those improvisations were usually not transcribed, so that only a few of his work for organ has survived. The five Preludes in E-flat major (1836–1837), Classified WAB 127 and WAB 128, as well as a few other WAB-unclassified works, which have been found in Bruckner's Präludienbuch, are probably not by Bruckner.

Bruckner's father died in 1837, when Bruckner was 13 years old. The teacher's position and house were given to a successor, and Bruckner was sent to the Augustinian monastery in Sankt Florian to become a choirboy. In addition to choir practice, his education included violin and organ lessons. Bruckner was in awe of the monastery's great organ, which was built during the late baroque era and rebuilt in 1837, and he sometimes played it during church services. Later, the organ was to be called the "Bruckner Organ". Despite his musical abilities, Bruckner's mother sent her son to a teaching seminar in Linz in 1841.

The three early masses (Windhaager Messe, Kronstorfer Messe and Messe für den Gründonnerstag), composed between 1842 and 1844, were short Austrian Landmessen for use in local churches and did not always set all the numbers of the ordinary. His Requiem in D minor of 1849 is the earliest work Bruckner himself considered worthy of preservation. It shows the clear influence of Mozart's Requiem (also in D minor) and similar works of Michael Haydn. The seldom performed Missa solemnis, composed in 1854 for Friedrich Mayer's installation, was the last major work Bruckner composed before he started to study with Simon Sechter, with the possible exception of Psalm 146, a large work, for SATB soloists, double choir and orchestra.

Prelate Michael Arneth noticed Bruckner's bad situation in Windhaag and awarded him a teacher's assistant position in the vicinity of the monastic town of Sankt Florian, sending him to Kronstorf an der Enns for two years. Here he would be able to have more of a part in musical activity. The time in Kronstorf was a much happier one for Bruckner. Between 1843 and 1845, Bruckner was the pupil of Leopold von Zenetti in Enns. Compared to the few works he wrote in Windhaag, the Kronstorf compositions from 1843–1845 show a significantly improved artistic ability, and finally the beginnings of what could be called "the Bruckner style". Among the Kronstorf works is the vocal piece Asperges me (WAB 4), which the young teacher's assistant, out of line of his position, signed with "Anton Bruckner m.p.ria. Comp[onist]". This has been interpreted as a lone early sign of Bruckner's artistic ambitions. Otherwise, little is known of Bruckner's life plans and intentions.

After the Kronstorf period, Bruckner returned to Sankt Florian in 1845, where, for the next 10 years, he would work as a Teacher and an organist. In May 1845, Bruckner passed an examination, which allowed him to begin work as an assistant Teacher in one of the village schools of Sankt Florian. He continued to improve his education by taking further courses, passing an examination giving him the permission to also teach in higher education institutes, receiving the grade "very good" in all disciplines. In 1848 Bruckner was appointed an organist in Sankt Florian and in 1851 this was made a regular position. In Sankt Florian, most of the repertoire consisted of the music of Michael Haydn, Johann Georg Albrechtsberger and Franz Joseph Aumann. During his stay in Sankt Florian Bruckner continued to work with Zenetti.

Bruckner's Two Aequali of 1847 for three trombones are solemn, brief works. The Military march of 1865 is an occasional work as a gesture of appreciation for the Militär-Kapelle der Jäger-Truppe of Linz. Abendklänge of 1866 is a short character piece for violin and piano.

In 1855, Bruckner, aspiring to become a student of the famous Vienna music theorist Simon Sechter, showed the master his Missa solemnis (WAB 29), written a year earlier, and was accepted. The education, which included skills in music theory and counterpoint among others, took place mostly via correspondence, but also included long in-person sessions in Vienna. Sechter's teaching would have a profound influence on Bruckner. Later, when Bruckner began teaching music himself, he would base his curriculum on Sechter's book Die Grundsätze der musikalischen Komposition (Leipzig 1853/54).

The three Masses, which Bruckner wrote in the 1860s and revised later on in his life, are more often performed. The Masses numbered 1 in D minor and 3 in F minor are for solo Singers, mixed choir, organ ad libitum and orchestra, while No. 2 in E minor is for mixed choir and a small group of wind instruments, and was written in an attempt to meet the Cecilians halfway. The Cecilians wanted to rid church music of instruments entirely. No. 3 was clearly meant for concert, rather than liturgical performance, and it is the only one of his Masses in which he set the first line of the Gloria, "Gloria in excelsis Deo", and of the Credo, "Credo in unum Deum", to music. In concert performances of the other Masses, these lines are intoned by a tenor soloist in the way a priest would, with a line of plainsong.

Bruckner also composed 20 Lieder, of which only a few have been published. The Lieder that Bruckner composed in 1861-1862 during his tuition by Otto Kitzler have not been WAB Classified. In 2013 the Austrian National Library was able to acquire a facsimile of the Kitzler-Studienbuch, the autograph manuscript hitherto unavailable to the public. The facsimile is edited by Paul Hawkshaw and Erich Wolfgang Partsch in Band XXV of Bruckner's Gesamtausgabe.

A String Quartet in C minor and the additional Rondo in C minor, also composed in 1862, were discovered decades after Bruckner's death. The later String Quintet in F Major of 1879, contemporaneous with the Fifth and Sixth symphonies, has been frequently performed. The Intermezzo in D minor, which was intended to replace its scherzo, is not frequently performed.

Bruckner composed also five name-day cantatas, as well as two patriotic cantatas, Germanenzug and Helgoland, on texts by August Silberstein. Germanenzug (WAB 70), composed in 1863–1864, was Bruckner's first published work. Helgoland (WAB 71), for TTBB men's choir and large orchestra, was composed in 1893 and was Bruckner's last completed composition and the only secular vocal work that he thought worthy enough to bequeath to the Austrian National Library.

In 1868, after Sechter had died, Bruckner hesitantly accepted Sechter's post as a Teacher of music theory at the Vienna Conservatory, during which time he concentrated most of his Energy on writing symphonies. These symphonies, however, were poorly received, at times considered "wild" and "nonsensical". His students at the Conservatory included Richard Robert.

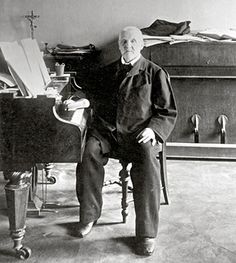

Bruckner was a renowned organist in his day, impressing audiences in France in 1869, and England in 1871, giving six recitals on a new Henry Willis organ at Royal Albert Hall in London and five more at the Crystal Palace. Though he wrote no major works for the organ, his improvisation sessions sometimes yielded ideas for the symphonies. He taught organ performance at the Conservatory; among his students were Hans Rott and Franz Schmidt. Gustav Mahler, who called Bruckner his "forerunner", attended the conservatory at this time.

He later accepted a post at the Vienna University in 1875, where he tried to make music theory a part of the curriculum. Overall, he was unhappy in Vienna, which was musically dominated by the critic Eduard Hanslick. At the time, there was a feud between advocates of the music of Wagner and Brahms; by aligning himself with Wagner, Bruckner made an unintentional enemy out of Hanslick. He was not without supporters, though. Deutsche Zeitung's music critic Theodor Helm, and famous conductors such as Arthur Nikisch and Franz Schalk constantly tried to bring his music to the public, and for this purpose proposed "improvements" for making Bruckner's music more acceptable to the public. While Bruckner allowed these changes, he also made sure in his will to bequeath his original scores to the Austrian National Library in Vienna, confident of their musical validity.

As a young man Bruckner sang in men's choirs and wrote music for them. Bruckner's secular choral music was mostly written for choral societies. The texts are always in German. Some of these works were written specifically for private occasions such as weddings, funerals, birthdays or name-days, many of these being dedicated to friends and acquaintances of the Composer. This music is rarely performed. Biographer Derek Watson characterizes the pieces for men's choir as being "of little concern to the non-German listener". Of about 30 such pieces, a most unusual and evocative composition is the song Abendzauber (1878) for men's choir, man soloist, yodelers and four horns.

Biographers generally characterize Bruckner as a "simple" provincial man, and many biographers have complained that there is huge discrepancy between Bruckner's life and his work. For Example, Karl Grebe said: "his life doesn't tell anything about his work, and his work doesn't tell anything about his life, that's the uncomfortable fact any biography must start from." Anecdotes abound as to Bruckner's dogged pursuit of his chosen craft and his humble acceptance of the fame that eventually came his way. Once, after a rehearsal of his Fourth Symphony in 1881, the well-meaning Bruckner tipped the Conductor Hans Richter: "When the symphony was over," Richter related, "Bruckner came to me, his face beaming with enthusiasm and joy. I felt him press a coin into my hand. 'Take this' he said, 'and drink a glass of beer to my health.'" Richter, of course, accepted the coin, a Maria Theresa thaler, and wore it on his watch-chain ever after.

In July 1886, the Emperor decorated him with the Order of Franz Joseph. He most likely retired from his position at the University of Vienna in 1892, at the age of 68. He wrote a great deal of music that he used to help teach his students.

Bruckner was a devoutly religious man, and composed numerous sacred works. He wrote a Te Deum, five psalm settings (including Psalm 150 in the 1890s), a Festive cantata, a Magnificat, about forty motets (among them eight settings of Tantum ergo, and three settings of both Christus factus est and Ave Maria), and at least seven Masses.

Bruckner never wrote an opera, and as much as he was a fan of Wagner's music dramas, he was uninterested in drama. In 1893 he thought about writing an opera called Astra based on a novel by Gertrud Bollé-Hellmund. Although he attended performances of Wagner's operas, he was much more interested in the music than the plot. After seeing Wagner's Götterdämmerung, he asked: "Tell me, why did they burn the woman at the end?" Nor did Bruckner ever write an oratorio.

Bruckner died in Vienna in 1896 at the age of 72. He is buried in the crypt of the monastery church at Sankt Florian, immediately below his favorite organ. He had always had a morbid fascination with death and dead bodies, and left explicit instructions regarding the embalming of his corpse.

Looking for authentic versions of the symphonies, Robert Haas produced during the 1930s a first critical edition of Bruckner's works based on the original scores. After World War II other scholars (Leopold Nowak, william Carragan, Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs et al.) carried on with this work.

The Anton Bruckner Private University for Music, Drama, and Dance, an institution of higher education in Linz, close to his native Ansfelden, was named after him in 1932 ("Bruckner Conservatory Linz" until 2004). The Bruckner Orchestra Linz was also named in his honor.

Decades after his death, the Nazis strongly approved of Bruckner's music because they saw it as expressing the zeitgeist of the German volk, and Hitler even consecrated a bust of Bruckner in a widely photographed ceremony in 1937 at Regensburg's Walhalla temple. Bruckner's music was among the most popular in Nazi Germany and the Adagio from his Seventh Symphony was broadcast by German radio (Deutscher Reichsrundfunk) when it broadcast the news of Hitler's death on 1 May 1945. However, this did not hurt Bruckner's standing in the postwar media, and several movies and TV productions in Europe and the United States have used excerpts from his music ever since the 1950s, as they already did in the 1930s. Nor did the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra ever ban Bruckner's music as they have Wagner's, even recording the Eighth Symphony with Zubin Mehta.

In addition, "Visconti used the music of Bruckner for his Senso (1954), its plot concerned with the Austrian invasion of Italy in the 1860s." The score by Carl Davis for the restoration of the 1925 film Ben-Hur takes "inspiration from Bruckner to achieve reverence in biblical scenes."

"The Bruckner Problem" refers to the difficulties and complications resulting from the numerous contrasting versions and editions that exist for most of the symphonies. The term gained currency following the publication (in 1969) of an article dealing with the subject, "The Bruckner Problem Simplified" by musicologist Deryck Cooke, which brought the issue to the attention of English-speaking Musicians.

A Symphonisches Präludium (Symphonic Prelude) in C minor was discovered by Mahler scholar Paul Banks in the Austrian National Library in 1974 in a piano duet transcription. Banks ascribed it to Gustav Mahler, and had it orchestrated by Albrecht Gürsching. In 1985 Wolfgang Hiltl, who had retrieved the original score by Rudolf Krzyzanowski, had it published by Doblinger (issued in 2002). According to scholar Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs, the stylistic examination of this "prelude" shows that it is all Bruckner's. Possibly Bruckner had given a draft-score to his pupil Krzyzanowski, which already contained the string parts and some important lines for woodwind and brass, as an exercise in instrumentation.

Nicholas Temperley writes in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (1980) that Bruckner

In 1990, The American Artist, Jack Ox, gave a paper called The Systematic Translation of Anton Bruckner's Eighth Symphony into a series of Thirteen Paintings at the Bruckner Symposium in Linz Austria; here she structurally analyzed all of the Eighth Symphony's themes. She then proceeded to show how she mapped this musical data into a series of twelve large, painted visualizations. The conference report was published in 1993,

The life of Bruckner was portrayed in Jan Schmidt-Garre's 1995 film Bruckner's Decision, which focuses on his recovery in the Austrian spa. Ken Russell's TV movie The Strange Affliction of Anton Bruckner, starring Peter Mackriel, also fictionalizes Bruckner's real-life stay at a sanatorium because of obsessive-compulsive disorder (or 'numeromania' as it was then described).

In the 2001 Second Edition of the New Grove, Mark Evan Bonds called the Bruckner symphonies "monumental in scope and design, combining lyricism with an inherently polyphonic design.... Bruckner favored an approach to large-scale form that relied more on large-scale thematic and harmonic juxtaposition. Over the course of his output, one senses an ever-increasing interest in cyclic integration that culminates in his masterpiece, the Symphony No. 8 in C minor, a work whose final page integrates the main themes of all four movements simultaneously."

Bruckner also wrote a Lancer-Quadrille (c. 1850) and a few other small works for piano. Most of this music was written for teaching purposes. Sixteen other pieces for piano, which Bruckner composed in 1862 during his tuition by Kitzler, have not been WAB Classified. A facsimile of these pieces is found in the Kitzler-Studienbuch.

In a concert review, Bernard Holland described parts of the first movements of Bruckner's sixth and seventh symphonies as follows: "There is the same slow, broad introduction, the drawn-out climaxes that grow, pull back and then grow some more – a sort of musical coitus interruptus."