Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Writer |

| Birth Day | February 18, 1934 |

| Birth Place | Harlem, New York City, United States |

| Age | 86 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | November 17, 1992(1992-11-17) (aged 58)\nSaint Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Cause of death | Liver cancer |

| Occupation | Poet, writer, activist, essayist, librarian |

| Education | Columbia University, Hunter College High School, Hunter College, National University of Mexico |

| Genre | Poetry, non-fiction |

| Literary movement | Civil rights |

| Notable works | The First Cities, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, The Cancer Journals |

Net worth: $19 Million (2024)

Audre Lorde, a prominent writer based in the United States, has amassed considerable wealth throughout her successful career. As of 2024, her net worth is estimated to be an impressive $19 million. Lorde has made significant contributions to the literary world, leaving an indelible mark with her powerful and thought-provoking works. Her remarkable talent and dedication to her craft have garnered her both critical acclaim and financial success. Lorde's influence as a writer extends beyond her impressive net worth, as she continues to inspire and empower individuals through her impactful words.

Biography/Timeline

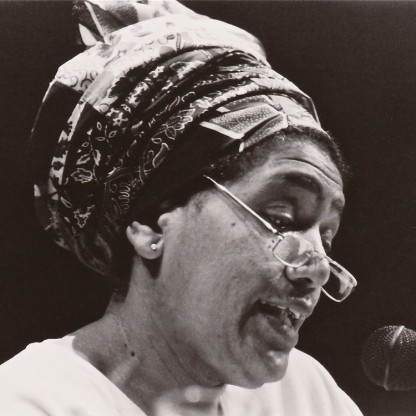

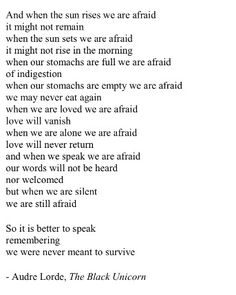

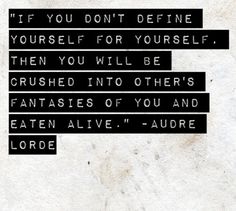

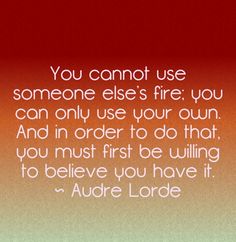

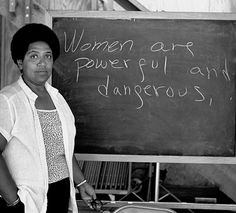

Audre Lorde (/ˈɔːdri lɔːrd/; born Audrey Geraldine Lorde; February 18, 1934 – November 17, 1992) was an American Writer, feminist, womanist, librarian, and civil rights Activist. As a poet, she is best known for technical mastery and emotional expression, as well as her poems that express anger and outrage at civil and social injustices she observed throughout her life. Her poems and prose largely deal with issues related to civil rights, feminism, and the exploration of black female identity.

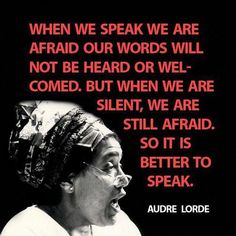

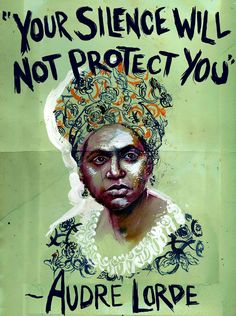

She attended Hunter College High School, a secondary school for intellectually gifted students, and graduated in 1951. While attending Hunter, Lorde published her first poem in Seventeen magazine after her school’s literary journal rejected it for being inappropriate. Also in high school, Lorde participated in poetry workshops sponsored by the Harlem Writers Guild, but noted that she always felt like somewhat of an outcast from the Guild. She felt she was not accepted because she “was both crazy and queer but [they thought] I would grow out of it all.”

In 1954, she spent a pivotal year as a student at the National University of Mexico, a period she described as a time of affirmation and renewal. During this time, she confirmed her identity on personal and artistic levels as both a lesbian and a poet. On her return to New York, Lorde attended Hunter College, and graduated in the class of 1959. While there, she worked as a librarian, continued writing, and became an active participant in the gay culture of Greenwich Village. She furthered her education at Columbia University, earning a master's degree in library science in 1961. During this period, she worked as a public librarian in nearby Mount Vernon, New York.

Lorde's criticism of feminists of the 1960s identified issues of race, class, age, gender and sexuality. Similarly, author and poet Alice Walker coined the term "womanist" in an attempt to distinguish black female and minority female experience from "feminism". While "feminism" is defined as "a collection of movements and ideologies that share a Common goal: to define, establish, and achieve equal political, economic, cultural, personal, and social rights for women" by imposing simplistic opposition between "men" and "women," the theorists and Activists of the 1960s and 1970s usually neglected the experiential difference caused by factors such as race and gender among different social groups.

In 1968, Lorde published The First Cities, her first volume of poems. It was edited by Diane di Prima, a former classmate and friend from Hunter College High School. The First Cities has been described as a "quiet, introspective book," and Dudley Randall, a poet and critic, asserted in his review of the book that Lorde "does not wave a black flag, but her blackness is there, implicit, in the bone".

Lorde taught in the Education Department at Lehman College from 1969 to 1970, then as a professor of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (part of the City University of New York) from 1970 to 1981. There, she fought for the creation of a black studies department. In 1981, she went on to teach at her alma mater, Hunter College (also CUNY), as the distinguished Thomas Hunter chair.

Lorde married attorney Edwin Rollins. She and Rollins divorced in 1970 after having two children, Elizabeth and Jonathan. In 1966, Lorde became head librarian at Town School Library in New York City, where she remained until 1968.

Nominated for the National Book Award for poetry in 1973, From a Land Where Other People Live (Broadside Press) shows Lorde's personal struggles with identity and anger at social injustice. The volume deals with themes of anger, loneliness, and injustice, as well as what it means to be an African-American woman, mother, friend, and lover.

1974 saw the release of New York Head Shop and Museum, which gives a picture of Lorde's New York through the lenses of both the civil rights movement and her own restricted childhood: stricken with poverty and neglect and, in Lorde's opinion, in need of political action.

Despite the success of these volumes, it was the release of Coal in 1976 that established Lorde as an influential voice in the Black Arts Movement, and the large publishing house behind it – Norton – helped introduce her to a wider audience. The volume includes poems from both The First Cities and Cables to Rage, and it unties many of the themes Lorde would become known for throughout her career: her rage at racial injustice, her celebration of her black identity, and her call for an intersectional consideration of women's experiences. Lorde followed Coal up with Between Our Selves (also in 1976) and Hanging Fire (1978).

From 1977 to 1978, Lorde had a brief affair with the Sculptor and Painter Mildred Thompson. The two met in Nigeria in 1977 at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC 77). Their affair ran its course during the time that Thompson lived in Washington, D.C.

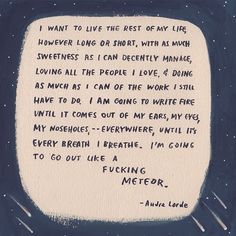

Lorde was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and underwent a mastectomy. Six years later, she was diagnosed with liver cancer. After her diagnosis, she wrote The Cancer Journals, which won the American Library Association Gay Caucus Book of the Year Award in 1981. She was featured as the subject of a documentary called A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, which shows her as an author, poet, human rights Activist, feminist, lesbian, a Teacher, a survivor, and a crusader against bigotry. She is quoted as saying: "What I leave behind has a life of its own. I've said this about poetry; I've said it about children. Well, in a sense I'm saying it about the very artifact of who I have been."

Lorde had several films that highlighted her journey as an Activist in the 1980s and 1990s.

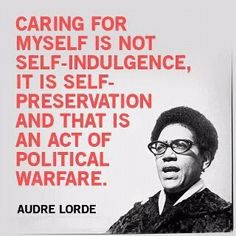

Lorde actively strove for the change of culture within the feminist community by implementing womanist ideology. In the journal "Anger Among Allies: Audre Lorde's 1981 Keynote Admonishing the National Women's Studies Association," it is stated that her speech contributed to communication with scholars' understanding of human biases. While "anger, marginalized communities, and US Culture" are the major themes of the speech, Lorde implemented various communication techniques to shift subjectivities of the "white feminist" audience. She further explained that "we are working in a context of oppression and threat, the cause of which is certainly not the angers which lie between us, but rather that virulent hatred leveled against all women, people of color, lesbians and gay men, poor people – against all of us who are seeking to examine the particulars of our lives as we resist our oppressions, moving towards coalition and effective action."

Lorde's deeply personal novel Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), described as a "biomythography," chronicles her childhood and adulthood. The narrative deals with the evolution of Lorde's sexuality and self-awareness.

The criticism was not one-sided: many white feminists were angered by Lorde's brand of feminism. In her 1984 essay "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House," Lorde attacked underlying racism within feminism, describing it as unrecognized dependence on the patriarchy. She argued that, by denying difference in the category of women, white feminists merely furthered old systems of oppression and that, in so doing, they were preventing any real, lasting change. Her argument aligned white feminists who did not recognize race as a feminist issue with white male slave-masters, describing both as "agents of oppression."

During her time in Mississippi she met Frances Clayton, a professor of psychology, who was to be her romantic partner until 1989.

From 1991 until her death, she was the New York State Poet Laureate. In 1992, she received the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement from Publishing Triangle. In 2001, Publishing Triangle instituted the Audre Lorde Award to honour works of lesbian poetry.

Lorde died of liver cancer at the age of 58 on November 17, 1992, in St. Croix, where she had been living with Gloria I. Joseph. In an African naming ceremony before her death, she took the name Gamba Adisa, which means "Warrior: She Who Makes Her Meaning Known".

The Audre Lorde Project, founded in 1994, is a Brooklyn-based organization for LGBT people of color. The organization concentrates on community organizing and radical nonviolent activism around progressive issues within New York City, especially relating to LGBT communities, AIDS and HIV activism, pro-immigrant activism, prison reform, and organizing among youth of color.

The Audre Lorde Award is an annual literary award presented by Publishing Triangle to honor works of lesbian poetry, first presented in 2001.

Lorde set out to confront issues of racism in feminist thought. She maintained that a great deal of the scholarship of white feminists served to augment the oppression of black women, a conviction that led to angry confrontation, most notably in a blunt open letter addressed to the fellow radical lesbian feminist Mary Daly, to which Lorde claimed she received no reply. Daly's reply letter to Lorde, dated 4 months later, was found in 2003 in Lorde's files after she died.

Contrary to this, Lorde was very open to her own sexuality and sexual awakening. In Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, her "biomythography" (a term coined by Lorde that combines "biography" and "mythology") she writes, "Years afterward when I was grown, whenever I thought about the way I smelled that day, I would have a fantasy of my mother, her hands wiped dry from the washing, and her apron untied and laid neatly away, looking down upon me lying on the couch, and then slowly, thoroughly, our touching and caressing each other's most secret places." According to scholar Anh Hua, Lorde turns female abjection – menstruation, female sexuality, and female Incest with the mother – into powerful scenes of female relationship and connection, thus subverting patriarchal heterosexist culture.

In 2014 Lorde was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display in Chicago, Illinois that celebrates LGBT history and people.

Lourde's life partner, black feminist, Dr. Gloria I. Joseph, resided together on Joseph's native land of St. Croix. Together they founded several organizations such as the Che Lumumba School for Truth, Women’s Coalition of St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, Sisterhood in Support of Sisters in South Africa, and Doc LOC Apiary.