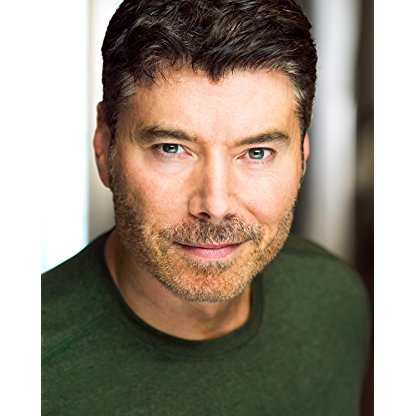

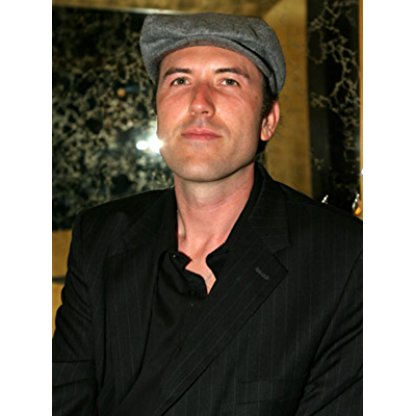

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Actor, Producer, Director |

| Birth Day | November 09, 1731 |

| Birth Place | Houston, Texas, United States |

| Age | 288 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | October 9, 1806(1806-10-09) (aged 74)\nBaltimore County, Maryland, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Leo |

| Other names | Benjamin Bannaker |

| Occupation | almanac author, surveyor, farmer |

| Parents | Robert (father) Mary Banneky (mother) |

Net worth

Benjamin Dane, a versatile talent in the entertainment industry, is projected to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M by 2024. With his diverse skill set as an actor, producer, and director, Dane has made a significant impact in the United States. Known for his dedication, creativity, and professionalism, he has built a strong reputation in the industry, garnering success through his various ventures. As he continues to make waves in the world of entertainment, Benjamin Dane's net worth is anticipated to grow substantially, reflecting his undeniable talent and entrepreneurial spirit.

Famous Quotes:

the Motions of the Sun and Moon, the True Places and Aspects of the Planets, the Rising and Setting of the Sun, Place and Age of the Moon, &c. – The Lunations, Conjunctions, Eclipses, Judgment of the Weather, Festivals, and other remarkable Days; Days for holding the Supreme and Circuit Courts of the United States, as also the useful Courts in Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. Also – several useful Tables, and valuable Receipts. – Various Selections from the Commonplace–Book of the Kentucky Philosopher, an American Sage; with interesting and entertaining Essays, in Prose and Verse –the whole comprising a greater, more pleasing, and useful Variety than any Work of the Kind and Price in North America.

Biography/Timeline

Benjamin Banneker was born on November 9, 1731, in Baltimore County, Maryland to Mary Banneky, a free black, and Robert, a freed slave from Guinea. There are two conflicting accounts of Banneker's family history. Banneker himself and his earliest biographers described him as having only African ancestry. None of Banneker's surviving papers describe a white ancestor or identify the name of his grandmother.

In 1737, Banneker was named at the age of 6 on the deed of his family's 100-acre (0.40 km) farm in the Patapsco Valley in rural Baltimore County. The remainder of his early life is not well documented. As a young teenager, he may have met and befriended Peter Heinrichs, a Quaker who established a school near the Banneker farm. Quakers were Leaders in the anti-slavery movement and advocates of racial equality (see Quakers in the abolition movement and Testimony of equality). Heinrichs may have shared his personal library and provided Banneker with his only classroom instruction. Banneker's formal education apparently ended when he was old enough to help on his family's farm.

In 1753 at the age of 22, Banneker completed a wooden clock that struck on the hour. He appears to have modeled his clock from a borrowed pocket watch by carving each piece to scale. The clock purportedly continued to work until Banneker's death.

After his father died in 1759, Banneker lived with his mother and sisters. In 1768, he signed a Baltimore County petition to move the county seat from Joppa to Baltimore.

In 1772, brothers Andrew Ellicott, John Ellicott and Joseph Ellicott moved from Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and bought land along the Patapsco Falls near Banneker's farm on which to construct gristmills, around which the village of Ellicott's Mills (now Ellicott City) subsequently developed. The Ellicotts were Quakers and shared the same views on racial equality as did many of their faith. Banneker studied the mills and became acquainted with their proprietors.

An English abolitionist, Thomas Day, had earlier written in a 1776 letter that had been published in Boston in 1784:

In 1788, George Ellicott, the son of Andrew Ellicott, loaned Banneker books and equipment to begin a more formal study of astronomy. During the following year, Banneker sent George his work calculating a solar eclipse.

In 1790, Banneker prepared an ephemeris for 1791, which he hoped would be placed within a published almanac. However, he was unable to find a printer that was willing to publish and distribute the almanac.

On the same day that he replied to Banneker (August 30, 1791), Jefferson sent a letter to the Marquis de Condorcet that contained the following paragraph relating to Banneker's race, abilities, almanac and work with Andrew Ellicott:

To further support this plea, Banneker included within the letter a handwritten manuscript of an almanac for 1792 containing his ephemeris with his astronomical calculations. He subsequently placed copies of the letter and Jefferson's reply in his journal and in a pamphlet printed and sold in Philadelphia in 1792 while publishers were distributing that almanac.

The 1793 almanac also contained a copy of "A Plan of a Peace-Office, for the United States" that Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, had authored. The Plan proposed the appointment of a "Secretary of Peace", described the Secretary's powers and advocated federal support and promotion of the Christian religion. The Plan stated:

The introduction to a 1795 Philadelphia edition contained a poem entitled: "Addressed to Benjamin Banneker". The verse began and ended:

In 1796, Banneker gave a manuscript of one of his almanacs to Suzanna Mason, a member of the Ellicott family who was visiting his home. In 1836, Mason's daughter wrote a published memoir of her mother's life, letters and manuscripts. The memoir contained a copy of a poem that Mason had sent to Banneker shortly after her 1796 visit. A portion of the verse stated:

Banneker kept a series of journals that contained his notebooks for astronomical observations, his diary and accounts of his dreams. The journals, only one of which escaped a fire on the day of his funeral, additionally contained a number of mathematical calculations and puzzles. The surviving journal described in April 1800 his recollections of the 1749, 1766 and 1783 emergences of Brood X of the seventeen-year periodical cicada, Magicicada septendecim, and stated that ".... they may be expected again in the year 1800, which is Seventeen years since their third appearance to me." The journal also recorded Banneker's observations on the hives and behavior of honey bees.

On the day of his funeral in 1806, a fire burned Banneker's log cabin to the ground, destroying many of his belongings and papers. A member of the Elllicott family, which had retained Banneker's only remaining journal, donated the document and other Banneker manuscripts to the Maryland Historical Society in 1987. The family also retained several items that Banneker had used after borrowing them from George Ellicott.

In 1809, three years after Banneker's death, Jefferson expressed a different opinion of Banneker in a letter to Joel Barlow that criticized a "diatribe" that a French abolitionist, Henri Grégoire, had written in 1808:

However, later biographers have contended that Banneker's mother was the child of Molly Welsh, a white indentured servant, and an African slave named Banneka. The first published description of Molly Welsh was based on interviews with her descendants that took place in 1836, long after the deaths of both Molly and Benjamin.

A United States postage stamp and the names of a number of recreational and cultural facilities, schools, streets and other facilities and institutions throughout the United States have commemorated Banneker's documented and mythical accomplishments throughout the years since he lived (see Commemorations of Benjamin Banneker). In 1983, Rita Dove, a Future Poet Laureate of the United States, wrote a biographical verse about Banneker while on the faculty of Arizona State University.

In 1996, a descendant of George Ellicott decided to sell at auction some of the items, including a table, candlesticks and molds. Although supporters of the planned Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum in Oella, Maryland, had hoped to obtain these and several other items related to Banneker and the Ellicotts, a Virginia investment banker won most of the items with a series of bids that totaled $49,750. The purchaser stated that he expected to keep some of the items and to donate the rest to the planned African American Civil War Memorial museum in Washington, D.C.