Age, Biography and Wiki

| Birth Day | May 31, 1916 |

| Birth Place | London, United Kingdom, United Kingdom |

| Age | 104 YEARS OLD |

| Birth Sign | Gemini |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Main interests | Oriental studies, Western philosophy, Middle Eastern philosophy |

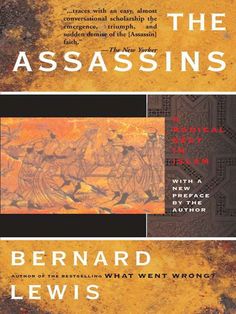

| Notable works | The Jews of Islam (1984) Islam and the West (1993) What Went Wrong? (2002) |

| Influenced | Heath W. Lowry, Fouad Ajami |

Net worth: $1.4 Billion (2024)

According to recent estimates, Bernard Lewis' net worth is projected to reach an impressive $1.4 billion by the year 2024. Bernard Lewis is a well-known figure in the fashion and retail industry, particularly in the United Kingdom. With his years of expertise and business ventures, he has successfully built a substantial fortune. Lewis' entrepreneurial acumen and keen eye for trends have undoubtedly contributed to his financial success.

Famous Quotes:

The meaning of genocide is the planned destruction of a religious and ethnic group, as far as it is known to me, there is no evidence for that in the case of the Armenians. [...] There is no evidence of a decision to massacre. On the contrary, there is considerable evidence of attempts to prevent it, which were not very successful. Yes there were tremendous massacres, the numbers are very uncertain but a million may well be likely... [and] the issue is not whether the massacres happened or not, but rather if these massacres were as a result of a deliberate preconceived decision of the Turkish government... there is no evidence for such a decision.

Biography/Timeline

In 1936, Lewis graduated from the School of Oriental Studies (now School of Oriental and African Studies, SOAS) at the University of London with a BA in history with special reference to the Near and Middle East. He earned his PhD three years later, also from SOAS, specializing in the history of Islam. Lewis also studied law, going part of the way toward becoming a solicitor, but returned to study Middle Eastern history. He undertook post-graduate studies at the University of Paris, where he studied with the orientalist Louis Massignon and earned the "Diplôme des Études Sémitiques" in 1937. He returned to SOAS in 1938 as an assistant lecturer in Islamic History.

During the Second World War, Lewis served in the British Army in the Royal Armoured Corps and as a Corporal in the Intelligence Corps in 1940–41 before being seconded to the Foreign Office. After the war, he returned to SOAS. In 1949, at the age of 33, he was appointed to the new chair in Near and Middle Eastern History.

Lewis' influence extends beyond academia to the general public. He is a pioneer of the social and economic history of the Middle East and is famous for his extensive research of the Ottoman archives. He began his research career with the study of medieval Arab, especially Syrian, history. His first article, dedicated to professional guilds of medieval Islam, had been widely regarded as the most authoritative work on the subject for about thirty years. However, after the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, scholars of Jewish origin found it more and more difficult to conduct archival and field research in the Arab countries, where they were suspected of espionage. Therefore, Lewis switched to the study of the Ottoman Empire, while continuing to research Arab history through the Ottoman archives which had only recently been opened to Western researchers. A series of articles that Lewis published over the next several years revolutionized the history of the Middle East by giving a broad picture of Islamic society, including its government, economy, and demographics.

In the mid-1960s, Lewis emerged as a commentator on the issues of the modern Middle East and his analysis of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the rise of militant Islam brought him publicity and aroused significant controversy. American Historian Joel Beinin has called him "perhaps the most articulate and learned Zionist advocate in the North American Middle East academic community". Lewis's policy advice has particular weight thanks to this scholarly authority. U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney remarked "in this new century, his wisdom is sought daily by policymakers, diplomats, fellow academics, and the news media."

The first two editions of Lewis' The Emergence of Modern Turkey (1961 and 1968) describe the Armenian Genocide as "the terrible holocaust of 1915, when a million and a half Armenians perished". In later editions, this text is altered to "the terrible slaughter of 1915, when, according to estimates, more than a million Armenians perished, as well as an unknown number of Turks." In this passage, Lewis argues that the deaths were the result of a struggle for the same land between two competing nationalist movements. Lewis was later one of 69 scholars to co-sign a 1985 petition asking the US Congress to avoid a resolution condemning the events as genocide.

In 1966, Lewis was a founding member of the learned society, Middle East Studies Association of North America (MESA), but in 2007 he broke away and founded Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa (ASMEA) to challenge MESA, which the New York Sun noted as "dominated by academics who have been critical of Israel and of America's role in the Middle East." The organization was formed as an academic society dedicated to promoting high standards of research and teaching in Middle Eastern and African studies and other related fields, with Lewis as Chairman of its academic council.

In 1974, aged 57, Lewis accepted a joint position at Princeton University and the Institute for Advanced Study, also located in Princeton, New Jersey. The terms of his appointment were such that Lewis taught only one semester per year, and being free from administrative responsibilities, he could devote more time to research than previously. Consequently, Lewis's arrival at Princeton marked the beginning of the most prolific period in his research career during which he published numerous books and articles based on previously accumulated materials. After retiring from Princeton in 1986, Lewis served at Cornell University until 1990.

Lewis is known for his literary debates with Edward Said, the Palestinian American literary theorist whose aim was to deconstruct what he called Orientalist scholarship. Said, who was a professor at Columbia University, characterized Lewis' work as a prime Example of Orientalism in his 1978 book Orientalism and in his later book Covering Islam. Said asserted that the field of Orientalism was political intellectualism bent on self-affirmation rather than objective study, a form of racism, and a tool of imperialist domination. He further questioned the scientific neutrality of some leading Middle East scholars, including Lewis, on the Arab World. In an interview with Al-Ahram weekly, Said suggested that Lewis' knowledge of the Middle East was so biased that it could not be taken seriously and claimed "Bernard Lewis hasn't set foot in the Middle East, in the Arab world, for at least 40 years. He knows something about Turkey, I'm told, but he knows nothing about the Arab world." Said considered that Lewis treats Islam as a monolithic entity without the nuance of its plurality, internal dynamics, and historical complexities, and accused him of "demagogy and downright ignorance." In Covering Islam, Said argued that "Lewis simply cannot deal with the diversity of Muslim, much less human life, because it is closed to him as something foreign, radically different, and other," and he criticised Lewis' "inability to grant that the Islamic peoples are entitled to their own cultural, political, and historical practices, free from Lewis' calculated attempt to show that because they are not Western... they can't be good."

Lewis argues that the Middle East is currently backward and its decline was a largely self-inflicted condition resulting from both culture and religion, as opposed to the post-colonialist view which posits the problems of the region as economic and political maldevelopment mainly due to the 19th-century European colonization. In his 1982 work Muslim Discovery of Europe, Lewis argues that Muslim societies could not keep pace with the West and that "Crusader successes were due in no small part to Muslim weakness." Further, he suggested that as early as the 11th century Islamic societies were decaying, primarily the byproduct of internal problems like "cultural arrogance," which was a barrier to creative borrowing, rather than external pressures like the Crusades.

In the wake of Soviet and Arab attempts to delegitimize Israel as a racist country, Lewis wrote a study of anti-Semitism, Semites and Anti-Semites (1986). In other works he argued Arab rage against Israel was disproportionate to other tragedies or injustices in the Muslim world, such as the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and control of Muslim-majority land in Central Asia, the bloody and destructive fighting during the Hama uprising in Syria (1982), the Algerian civil war (1992–98), and the Iran–Iraq War (1980–88).

Lewis views Christendom and Islam as civilizations that have been in perpetual collision since the advent of Islam in the 7th century. In his essay The Roots of Muslim Rage (1990), he argued that the struggle between the West and Islam was gathering strength. According to one source, this essay (and Lewis' 1990 Jefferson Lecture on which the article was based) first introduced the term "Islamic fundamentalism" to North America. This essay has been credited with coining the phrase "clash of civilizations", which received prominence in the eponymous book by Samuel Huntington. However, another source indicates that Lewis first used the phrase "clash of civilizations" at a 1957 meeting in Washington where it was recorded in the transcript.

Rejecting the view that Western scholarship was biased against the Middle East, Lewis responded that Orientalism developed as a facet of European humanism, independently of the past European imperial expansion. He noted the French and English pursued the study of Islam in the 16th and 17th centuries, yet not in an organized way, but long before they had any control or hope of control in the Middle East; and that much of Orientalist study did nothing to advance the cause of imperialism. In his 1993 book Islam and the West, Lewis wrote "What imperial purpose was served by deciphering the ancient Egyptian language, for Example, and then restoring to the Egyptians knowledge of and pride in their forgotten, ancient past?"

In 1998, Lewis read in a London-based newspaper Al-Quds Al-Arabi a declaration of war on the United States by Osama bin Laden. In his essay "A License to Kill", Lewis indicated he considered bin Laden's language as the "ideology of jihad" and warned that bin Laden would be a danger to the West. The essay was published after the Clinton administration and the US intelligence community had begun its hunt for bin Laden in Sudan and then in Afghanistan.

In addition to his scholarly works, Lewis wrote several influential books accessible to the general public: The Arabs in History (1950), The Middle East and the West (1964), and The Middle East (1995). In the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks, the interest in Lewis's work surged, especially his 1990 essay The Roots of Muslim Rage. Three of his books were published after 9/11: What Went Wrong? (written before the attacks), which explored the reasons of the Muslim world's apprehension of (and sometimes outright hostility to) modernization; The Crisis of Islam; and Islam: The Religion and the People.

In 2002, Lewis wrote an article for the Wall Street Journal regarding the buildup to the Iraq War entitled "Time for Toppling", where he stated his opinion that "a regime change may well be dangerous, but sometimes the dangers of inaction are greater than those of action." In 2007, Jacob Weisberg described Lewis as "perhaps the most significant intellectual influence behind the invasion of Iraq". Michael Hirsh attributed to Lewis the view that regime change in Iraq would provide a jolt that would "modernize the Middle East" and suggested that Lewis' allegedly 'orientalist' theories about "what went wrong" in the Middle East, and other writings, formed the intellectual basis of the push towards war in Iraq.

Lewis' article received significant press coverage. However, the day passed without any incident. In his 2009 book Engaging the Muslim World, the American academic Juan Cole responded that there was no evidence to suggest that Iran had been working on a nuclear weapon for fifteen years. He also disagreed with Lewis' suggestion that Ahmadinejad "might deploy this weapon against Israel on 22 August 2006".

In 2007 and 1999, respectively, Lewis was called "the West’s leading interpreter of the Middle East" and "the most influential postwar Historian of Islam and the Middle East." His advice was frequently sought by neoconservative policymakers, including the Bush administration. Lewis, therefore, is generally regarded as the dean of Middle East scholars. However, his support of the Iraq War and neoconservative ideals have since come under scrutiny.

Writing in 2008, Lewis did not advocate imposing freedom and democracy on Islamic nations. "There are things you can't impose. Freedom, for Example. Or democracy. Democracy is a very strong Medicine which has to be administered to the patient in small, gradually increasing doses. Otherwise, you risk killing the patient. In the main, the Muslims have to do it themselves."