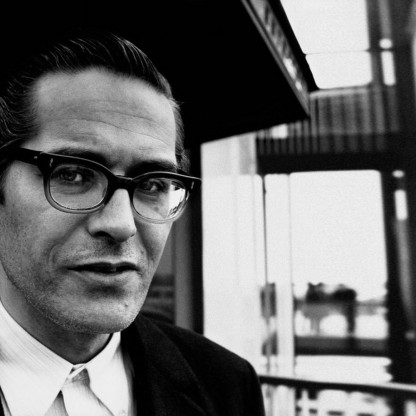

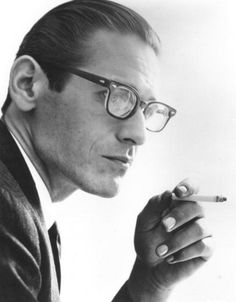

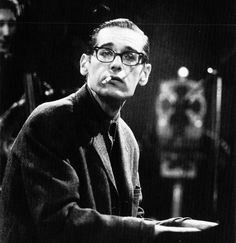

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Birth Day | August 16, 1929 |

| Birth Place | Plainfield, New Jersey, United States, United States |

| Age | 91 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | September 15, 1980(1980-09-15) (aged 51)\nNew York City, New York |

| Birth Sign | Virgo |

| Birth name | William John Evans |

| Genres | Jazz, modal jazz, third stream, cool jazz, post-bop |

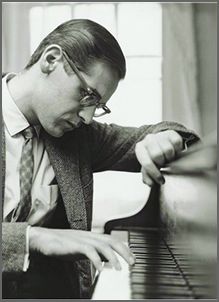

| Occupation(s) | Musician Composer Arranger |

| Instruments | Piano |

| Years active | 1950s–1980 |

| Labels | Riverside, Verve, Fantasy |

| Associated acts | George Russell, Miles Davis, Cannonball Adderley, Philly Joe Jones, Scott LaFaro, Paul Motian, Eddie Gómez, Marty Morell, Tony Bennett, Jim Hall, Stan Getz, Monica Zetterlund, Chet Baker |

Net worth: $10 Million (2024)

Bill Evans, a renowned musician and composer from the United States, is well-regarded for his exceptional talent and contribution to the world of jazz. As of 2024, his net worth is estimated to be approximately $10 million, highlighting both his successful career and financial accomplishments. Bill Evans has left an indelible mark on the music industry with his remarkable piano skills and influential compositions, which have captivated audiences worldwide. His profound impact on the jazz genre solidifies his position as one of the most esteemed musicians of his time.

Biography/Timeline

Born in Plainfield, New Jersey, in 1929, he was classically trained, and studied at Southeastern Louisiana University and the Mannes School of Music, where he majored in composition and received the Artist Diploma. In 1955, he moved to New York City, where he worked with bandleader and theorist George Russell. In 1958, Evans joined Miles Davis's sextet, where he was to have a profound influence. In 1959, the band, then immersed in modal jazz, recorded Kind of Blue, the best-selling jazz album of all time. During that time, Evans was also playing with Chet Baker for the album Chet.

After high school, in September 1946, Evans attended Southeastern Louisiana University on a flute scholarship. He studied classical piano interpretation with Louis P. Kohnop, John Venettozzi, and Ronald Stetzel. A key part in Evans' development was Gretchen Magee, whose methods of teaching left an important print in his composition style. Soon, Bill would compose his first tune.

Evans' heroin addiction began in the late 1950s, and increased following LaFaro's death. His girlfriend Ellaine was also an addict. Evans habitually had to borrow money from friends, and eventually, his electricity and telephone services were shut down. Evans said, "You don't understand. It's like death and transfiguration. Every day you wake in pain like death and then you go out and score, and that is transfiguration. Each day becomes all of life in microcosm."

During his three-year (1951–54) stay in the army, Evans played flute, piccolo, and piano in the Fifth U.S. Army Band at Fort Sheridan. He also hosted a jazz program on the camp radio station and occasionally performed in Chicago clubs, where he met singer Lucy Reed, with whom he became friends and would later record. He also met singer and Bassist Bill Scott and Chicago jazz Pianist Sam Distefano (his bunkmate in their platoon), both of whom became Evans' close friends. Evans' stay in the army was traumatic, and he had nightmares for years. As people criticized his musical conceptions and playing, he lost his confidence for the first time. Around 1953 Evans composed his most well known tune, "Waltz for Debby", for his young niece. During this period, in which Evans was met with universal acclaim, he began using recreational drugs, occasionally smoking marijuana.

Evans was discharged from the Army in January 1954, and entered a period of seclusion, triggered by the harsh criticism he had received. He took a sabbatical year and went to live with his parents, where he set up a studio, acquired a grand piano and worked on his technique. The self-critical Evans believed he lacked the natural fluidity of other Musicians. He visited his brother Harry, now in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, recently married and working as a conservatory Teacher.

In early 1955, singer Lucy Reed moved to New York City to play at the Village Vanguard and The Blue Angel, and in August she recorded The Singing Reed with a group which included Evans. During this period, he met two of Reed's friends: manager Helen Keane, who, seven years later, would become his own agent; and George Russell, with whom he would soon work. That year, he also made his first recording, in a small ensemble, in Dick Garcia's A Message from Garcia. In parallel, Evans kept with his work with Scott, playing in Preview's Modern Jazz Club in Chicago during December–January 1956/7, and recording The Complete Tony Scott. After the Complete sessions, Scott left for a long overseas tour.

In September 1956, Producer Orrin Keepnews was convinced to record the reluctant Evans by a demo tape Mundell Lowe played to him over the phone. The result was his debut album, New Jazz Conceptions, featuring the original versions of "Waltz for Debby", and "Five". This album began Evans' relationship with Riverside Records. Although a critical success that gained positive reviews in Down Beat and Metronome magazines, New Jazz Conceptions was initially a financial failure, selling only 800 copies the first year. "Five" was for some time Evans' trio farewell tune during performances. After releasing the album, Evans spent much time studying Bach scores to improve his technique.

In 1957, Russell was one of six Musicians (three jazz, three classical composers) commissioned by Brandeis University to write a piece for their Festival of the Creative Arts in the context of the first experiments in third stream jazz. Russell wrote a suite for orchestra, "All About Rosie", which featured Bill Evans among other soloists. "All About Rosie" has been cited as one of the few convincing examples of composed polyphony in jazz. A week before the festival, the piece was previewed on TV, and Evans' performance was deemed "legendary" in jazz circles. During the festival performance, in June 6, Evans became acquainted with Chuck Israels, who would become his Bassist years later. During the Brandeis Festival, Guitarist Joe Puma invited Evans to play on the album Joe Puma/Jazz.

Evans left Davis' sextet in November 1958 and stayed with his parents in Florida and his brother in Louisiana. While he was burned out, one of the main reasons for leaving was his father's illness. During this sojourn, the always self-critical Evans suddenly felt his playing had improved. "While I was staying with my brother in Baton Rouge, I remember finding that somehow I had reached a new level of expression in my playing. It had come almost automatically, and I was very anxious about it, afraid I might lose it."

In mid-1959 Scott LaFaro, who was playing up the street from Evans, said he was interested in developing a trio. LaFaro suggested Paul Motian, who had already appeared in some of Evans' first solo albums, as the Drummer for the new band. The trio with LaFaro and Motian became one of the most celebrated piano trios in jazz. With this group Evans' focus settled on traditional jazz standards and original compositions, with an added emphasis on interplay among band members. Evans and LaFaro would achieve a high level of musical empathy. In December 1959 the band recorded its first album, Portrait in Jazz for Riverside Records.

Evans' career began just before the rock explosion in the 1960s. During this decade, jazz was swept in a corner, and most new talents had few opportunities to gain recognition, especially in America. However, Evans believed he had been lucky to gain some exposure before this profound change in the music world, and never had problems finding employers and recording opportunities.

When he re-formed his trio in 1962, two albums, Moon Beams and How My Heart Sings! resulted. In 1963, after having switched from Riverside to the much more widely distributed Verve (for financial reasons related to his drug addiction), he recorded Conversations with Myself, an innovative album which featured overdubbing, layering up to three individual tracks of piano for each song. The album won him his first Grammy award.

In summer 1963, Evans and his girlfriend Ellaine left their flat in New York and settled in his parents' home in Florida, where, it seems, they quit the habit for some time. Even though never legally married, Bill and Ellaine were in all respects man and wife. At that time, Ellaine meant everything to Bill, and was the only person with whom he felt genuine comfort.

In an interview given in 1964, Evans described Bud Powell as his single greatest influence.

In 1965, the trio with Israels and Bunker went on a well-received European tour and recorded a BBC special.

In 1966, Evans discovered the young Puerto Rican Bassist Eddie Gómez. In what turned out to be an eleven-year stay, Gómez sparked new developments in Evans' trio conception. One of the most significant releases during this period is Bill Evans at the Montreux Jazz Festival (1968), where he won his second Grammy award. It has remained a critical favorite, and is one of only two albums Evans made with Drummer Jack DeJohnette.

In 1968, Drummer Marty Morell joined the trio and remained until 1975, when he retired to family life. This was Evans' most stable, longest-lasting group. Evans had overcome his heroin habit and was entering a period of personal stability.

Between 1969 and 1970 Evans recorded From Left to Right, featuring his first use of electric piano.

While Evans considered himself an acoustic Pianist, from the 1970 album From Left to Right on, he also released some material with Fender-Rhodes piano intermissions. However, unlike other jazz players (e.g. Herbie Hancock) he never fully embraced the new instrument, and invariably ended up returning to the acoustic sound. "I don't think too much about the electronic thing, except that it's kind of fun to have it as an alternate voice. (...) [It's] merely an alternate keyboard instrument, that offers a certain kind of sound that's appropriate sometimes. I find that it's a refreshing auxiliary to the piano—but I don't need it (...) I don't enjoy spending a lot of time with the electric piano. I play it for a period of time, then I quickly tire of it, and I want to get back to the acoustic piano." He commented that electronic music: "just doesn't attract me. I'm of a certain period, a certain evolution. I hear music differently. For me, comparing electric bass to acoustic bass is sacrilege."

Between May and June 1971 Evans recorded The Bill Evans Album, which won two Grammy awards. This all-originals album (4 new), also featured alternation between acoustic and electric piano. One of these was "Comrade Conrad", a tune that had originated as a Crest toothpaste jingle and had later been reelaborated and dedicated to Conrad Mendenhall, a friend who had died in a car accident.

In 1973, while working in Redondo Beach, California, Evans met and fell in love with Nenette Zazzara, despite his long-term relationship with Ellaine. When Evans broke the news to Ellaine, she pretended to understand, but then committed suicide by throwing herself under a subway train. Evans' relatives believe that Ellaine's infertility, coupled with Bill's Desire to have a son, may have influenced those events. As a result, Evans went back on heroin for a while, then got into a methadone treatment program. In August 1973, Evans married Nenette, and, in 1975, they had a child, Evan. The new family, which also included Evans' stepdaughter Maxine, lived in a large house in Closter, New Jersey. Both remained very close until his death. Nenette and Bill remained married until Bill's death in 1980.

In 1975, Morell was replaced by Drummer Eliot Zigmund. Several collaborations followed, and it was not until 1977 that the trio was able to record an album together. Both I Will Say Goodbye (Evans' last album for Fantasy Records) and You Must Believe in Spring (for Warner Bros.) highlighted changes that would become significant in the last stage of Evans' life. A greater emphasis was placed on group improvisation and interaction, and new harmonic experiments were attempted.

At the beginning of his career, Evans used block chords heavily. He later abandoned them in part. During a 1978 interview, Marian McPartland asked:

In August 1979, Evans recorded his last studio album, We Will Meet Again, featuring a composition of the same name written for his brother. The album won a Grammy award posthumously in 1981, along with I Will Say Goodbye.

On September 15, 1980, Evans, who had been in bed for several days with stomach pains at his home in Fort Lee, was accompanied by Joe LaBarbera and Verchomin to the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, where he died that afternoon. The cause of death was a combination of peptic ulcer, cirrhosis, bronchial pneumonia, and untreated hepatitis. Evans' friend Gene Lees described Evans' struggle with drugs as "the longest suicide in history." He was interred in Baton Rouge, next to his brother Harry. Services were held in Manhattan on Friday, September 19. A tribute, planned by Producer Orrin Keepnews and Tom Bradshaw, was held on the following Monday, September 22, at the Great American Music Hall in San Francisco. Fellow Musicians paid homage to the late Pianist in the first days of the 1980 Monterey Jazz Festival, which had opened that very week: Dave Brubeck played his own "In Your Own Sweet Way" on the 19th, The Manhattan Transfer would follow on the 20th, while John Lewis dedicated "I'll Remember April".

During his lifetime, Evans was honored with 31 Grammy nominations and seven Awards. In 1994, he was posthumously honored with the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

When the television miniseries Jazz was released in 2001, it was criticised for neglecting Evans' work after his departure from the Miles Davis' sextet.

Other highlights from this period include "Solo – In Memory of His Father" from Bill Evans at Town Hall (1966), which also introduced "Turn Out the Stars"; a second pairing with Guitarist Jim Hall, Intermodulation (1966); and the solo album Alone (1968, featuring a 14-minute version of "Never Let Me Go"), that won his third Grammy award.

Music critic Richard S. Ginell noted: "With the passage of time, Bill Evans has become an entire school unto himself for Pianists and a singular mood unto himself for listeners. There is no more influential jazz-oriented pianist—only McCoy Tyner exerts nearly as much pull among younger players and journeymen."