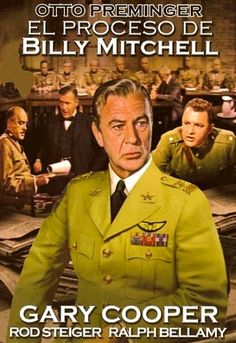

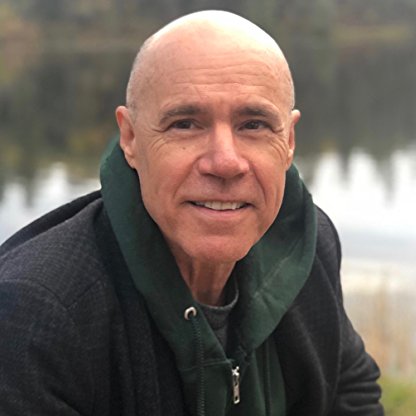

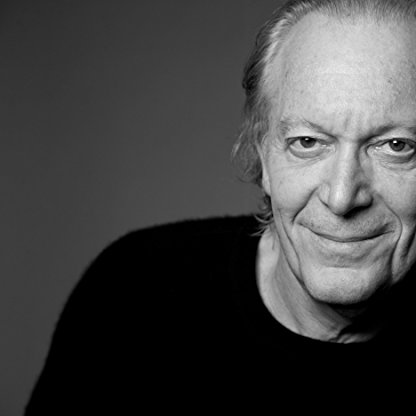

Age, Biography and Wiki

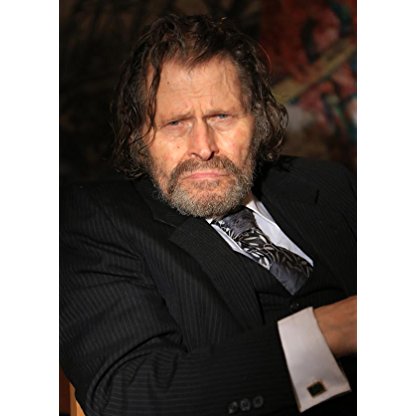

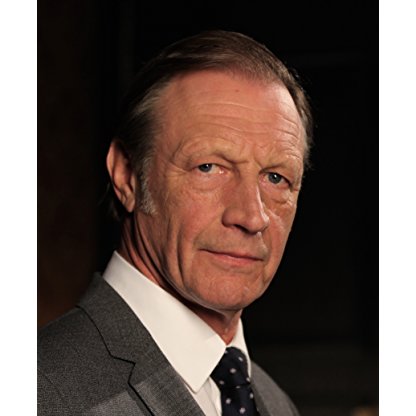

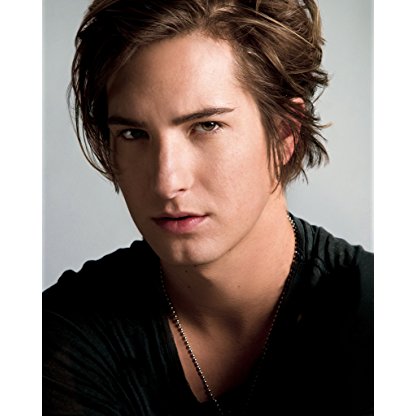

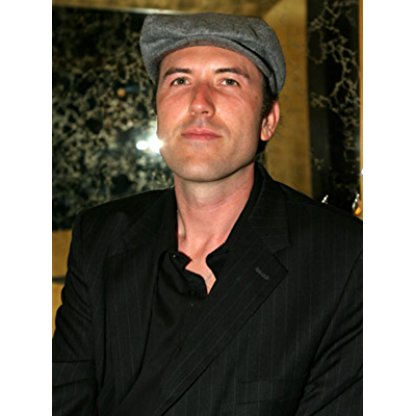

| Who is it? | Actor |

| Birth Day | December 29, 1879 |

| Age | 140 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | February 19, 1936(1936-02-19) (aged 56)\nNew York City, New York |

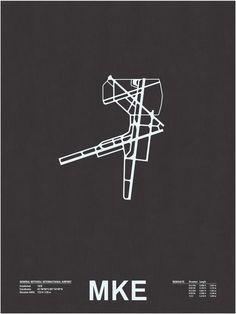

| Buried | Forest Home Cemetery, Milwaukee, Wisconsin |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/branch | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1898–1926 |

| Rank | Major General (posthumous) |

| Commands held | Air Service, Third Army – AEF |

| Battles/wars | Spanish–American War World War I Battle of Saint-Mihiel The Lost Battalion |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Cross Distinguished Service Medal World War I Victory Medal Congressional Gold Medal (posthumous) |

Net worth

Billy J. Mitchell, widely recognized for his acting prowess, boasts an estimated net worth ranging from $100K to $1M as of 2024. Born in 1879, Mitchell's remarkable career spans across several decades, leaving an indelible mark in the film industry. Throughout his illustrious journey, he has cunningly portrayed numerous characters, capturing the hearts of audiences worldwide. With his exceptional talent and dedication, Mitchell has accumulated considerable wealth, cementing his status as a noteworthy actor in the annals of cinematic history.

Famous Quotes:

...sea craft of all kinds, up to and including the most modern battleships, can be destroyed easily by bombs dropped from aircraft, and further, that the most effective means of destruction are bombs. [They] demonstrated beyond a doubt that, given sufficient bombing planes—in short an adequate air force—aircraft constitute a positive defense of our country against hostile invasion.

Biography/Timeline

William Lendrum Mitchell (December 29, 1879 – February 19, 1936) was a United States Army general who is regarded as the father of the United States Air Force.

Billy Mitchell graduated from Columbian College of George Washington University, where he was a member of Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity. He then enlisted as a private at age 18 in Company M of the 1st Wisconsin Infantry Regiment on May 14, 1898, early in the Spanish–American War. Quickly gaining a commission due to his father's influence, he joined the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

Following the cessation of hostilities, Mitchell remained in the Army. From 1900 to 1904, Mitchell was posted in the District of Alaska as a lieutenant in the Signal Corps. On May 26, 1900, the United States Congress appropriated $450,000 in order to establish a communications system to connect the many isolated and widely separated U.S. Army outposts and civilian Gold Rush camps in Alaska by telegraph. Along with Captain George C. Brunnell, Lieutenant Mitchell oversaw the construction of what became known as the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System (WAMCATS). He predicted as early as 1906, while an instructor at the Army's Signal School in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, that Future conflicts would take place in the air, not on the ground.

A member of one of Milwaukee's most prominent families, Billy Mitchell was probably the first person with ties to Wisconsin to see the Wright Brothers plane fly. In 1908, when a young Signal Corps officer, Mitchell observed Orville Wright's flying demonstration at Fort Myer, Virginia. Mitchell took FLIGHT lessons at the Curtiss Aviation School at Newport News, Virginia.

In March 1912, after assignments in the Philippines that saw him tour battlefields of the Russo-Japanese War and conclude that war with Japan was inevitable one day, Mitchell was one of 21 officers selected to serve on the General Staff—at the time, its youngest member at age 32. Ironically, he appeared in August 1913 at legislative hearings considering a bill to make Army aviation a branch separate from the Signal Corps and testified against the bill. As the only Signal Corps officer on the General Staff, he was chosen as temporary head of the Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps, a predecessor of the present day United States Air Force, in May 1916, when its head was reprimanded and relieved of duty for malfeasance in the section. Mitchell administered the section until the new head, Lieutenant Colonel George O. Squier, arrived from attaché duties in London, England, where World War I was in progress, then became his permanent assistant. In June, he took private flying lessons at the Curtiss Flying School because he was proscribed by law from aviator training by age and rank, at an expense to himself of $1,470 (approximately $33,000 in 2015). In July 1916, he was promoted to major and appointed Chief of the Air Service of the First Army.

When the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, Mitchell was in Spain en route to France as an observer. He arrived in Paris on April 10, and set up an office for the Aviation Section from which he collaborated extensively with British and French air Leaders such as General Hugh Trenchard, studying their strategies as well as their aircraft. On April 24, he made the first FLIGHT by an American officer over German lines, flying with a French pilot. Before long, Mitchell had gained enough experience to begin preparations for American air operations. Mitchell rapidly earned a reputation as a daring, flamboyant, and tireless leader. In May, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He was promoted to the temporary rank of colonel on October 10, 1917 to rank from August 5.

In September 1918, he planned and led nearly 1,500 British, French, and Italian aircraft in the air phase of the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, one of the first coordinated air-ground offensives in history. He was elevated to the rank of (temporary) brigadier general on October 14, 1918 and commanded all American air combat units in France. He ended the war as Chief of Air Service, Group of Armies, and became Chief of Air Service, Third Army after the armistice.

Mitchell believed that the use of floating bases was necessary to defend the nation against naval threats, but the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral william S. Benson, had dissolved Naval Aeronautics as an organization early in 1919, a decision later reversed by Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt. However, senior Naval Aviators feared that land-based aviators in a "unified" independent air force would no more understand the requirements of sea-based aviation than ground forces commanders understood the capabilities and potential of air power, and vigorously resisted any alliance with Mitchell.

The Navy reluctantly agreed to the demonstration after news leaked of its own tests. To counter Mitchell, the Navy had sunk the old battleship Indiana near Tangier Island, Virginia, on November 1, 1920, using its own airplanes. Daniels had hoped to squelch Mitchell by releasing a report on the results written by Captain william D. Leahy stating that, "The entire experiment pointed to the improbability of a modern battleship being either destroyed or completely put out of action by aerial bombs." When the New-York Tribune revealed that the Navy's "tests" were done with dummy sand bombs and that the ship was actually sunk using high explosives placed on the ship, Congress introduced two resolutions urging new tests and backed the Navy into a corner.

Mitchell was dispatched by President Harding to West Virginia to stop the warfare that had broken out between the United Mine Workers, Stone Mountain Coal Company, the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency, and other groups after the Matewan Massacre. Miners outraged by the ambush slaying of Matewan Police Chief Sid Hatfield by agents for the coal company marched on Mingo and Logan County leading to the Battle of Blair Mountain, August 25 to September 2, 1921. On August 26, Mitchell commanded Army bombers from Maryland to Charleston, West Virginia. Mitchell told the press that Army bombers alone could end the "Mingo War" by dropping tear gas on the miners. A private army of 3,000 led by Sheriff Don Chafin and financed by the Coal Operators Association engaged in gun battles and used private planes to drop dynamite charges and World War I surplus gas and explosive bombs against an estimated 13,000 miners. Neither side responded to President Harding's August 30 proclamation to cease hostilities. In the last days of the civil disturbance, Mitchell's bombers flew several reconnaissance missions but did not engage in combat; one bomber crashed on a return FLIGHT, killing three crew members. On September 3, surrounded by 2,000 Army troops, Chafin's force dispersed and most miners went home although some surrendered to the Army. Later, Mitchell cited the "Mingo War" as an Example of the potential for air power in civil disturbances.

In 1922, while in Europe for General Patrick, Mitchell met the Italian air power theorist Giulio Douhet and soon afterwards an excerpted translation of Douhet's The Command of the Air began to circulate in the Air Service. In 1924, Gen. Patrick again dispatched him on an inspection tour, this time to Hawaii and Asia, to get him off the front pages. Mitchell came back with a 324-page report that predicted Future war with Japan, including the attack on Pearl Harbor. Of note, Mitchell discounted the value of aircraft carriers in an attack on the Hawaiian Islands, believing they were of little practical use because they were incapable of operating effectively on the high seas, nor capable of delivering "sufficient aircraft in the air at one time to insure a concentrated operation." Mitchell believed instead, a surprise attack on the Hawaiian Islands would be conducted by land-based aircraft operating from islands in the Pacific. His report, published in 1925 as the book Winged Defense, foretold wider benefits of an investment in air power, believing it at the time, and for the Future, " a dominating factor in the world's development", both for national defense and economic benefit. Winged Defense sold only 4,500 copies between August 1925 and January 1926, the months surrounding the publicity of the court martial, and so Mitchell did not reach a wide audience.

However, the court found the truth or falsity of Mitchell's accusations to be immaterial to the charge and on December 17, 1925, found him "guilty of all specifications and of the charge". The court suspended him from active duty for five years without pay, which President Coolidge later amended to half-pay. The generals ruling in the case wrote, "The Court is thus lenient because of the military record of the Accused during the World War." MacArthur (who himself in 1951 was removed from duty for similar reasons) later said he had voted to acquit, and Fiorello La Guardia said that MacArthur's "not guilty" ballot had been found in the judges' anteroom. MacArthur felt "that a senior officer should not be silenced for being at variance with his superiors in rank and with accepted doctrine."

Mitchell viewed the election of his one-time antagonist Franklin D. Roosevelt as advantageous for air power, and met with him early in 1932 to brief him on his concepts for a unification of the military in a Department of Defense. His ideas intrigued and interested Roosevelt. Mitchell believed he might receive an appointment as Assistant Secretary of War for Air or perhaps even Secretary of War in a Roosevelt administration, but neither prospect materialized.

In 1926, Mitchell made his home with his wife Elizabeth at the 120-acre (0.5 km) Boxwood Farm in Middleburg, Virginia, which remained his primary residence until his death. He died of a variety of ailments, including a bad heart and an extreme case of influenza, in a hospital in New York City on February 19, 1936, at the age of 56, and was buried at Forest Home Cemetery in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Mitchell's concept of a battleship's vulnerability to air attack under "war-time conditions" would be vindicated after his death. Air power was first shown to be decisive against a capital ship in war conditions during the Spanish Civil War:- on 29 May 1937, Republican Government bombers attacked and damaged the German pocket battleship Deutschland. This new dimension for aerial warfare precedes the attack on Taranto and Pearl Harbor by a good margin.

Mitchell's son, John, joined the Army in 1941. Promoted to first lieutenant in the 4th Armored Division, he died from a blood infection in 1942. Mitchell's first cousin, the Canadian George Croil, went on to secure an autonomous status for the Royal Canadian Air Force and in 1938 became its first Chief of the Air Staff.

Note – the date listed is the date the promotion was accepted by General Mitchell. The actual date of rank was usually a few days earlier. (Source – Army Register, 1926. pg. 423.)