Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Actress |

| Birth Day | August 20, 1833 |

| Age | 186 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | March 13, 1901(1901-03-13) (aged 67)\nIndianapolis, Indiana, U.S. |

| Vice President | Levi P. Morton |

| Preceded by | Joseph McDonald |

| Succeeded by | David Turpie |

| Cause of death | Pneumonia |

| Resting place | Crown Hill Cemetery Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican (1856–1901) |

| Other political affiliations | Whig Party (Before 1856) |

| Spouse(s) | Caroline Scott (m. 1853; d. 1892) Mary Scott Lord (m. 1896) |

| Children | Russell Mary Elizabeth |

| Parents | John Scott Harrison (father) Elizabeth Ramsey (mother) |

| Education | Farmer's College Miami University |

| Profession | Politician Lawyer |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1862–1865 |

| Rank | Colonel Brevet Brigadier General |

| Unit | Army of the Cumberland |

| Commands | 70th Indiana Infantry Regiment 1st Brigade, 1st Division, XX Corps |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Benjamin Harrison | President1889–1893 |

| Levi P. Morton | Vice President1889–1893 |

| James G. Blaine | Secretary of State1889–1892 |

| John W. Foster | 1892–1893 |

| William Windom | Secretary of Treasury1889–1891 |

| Charles W. Foster | 1891–1893 |

| Redfield Proctor | Secretary of War1889–1891 |

| Stephen B. Elkins | 1891–1893 |

| William H. H. Miller | Attorney General1889–1893 |

| John Wanamaker | Postmaster General1889–1893 |

| Benjamin F. Tracy | Secretary of the Navy1889–1893 |

| John W. Noble | Secretary of the Interior1889–1893 |

| Jeremiah M. Rusk | Secretary of Agriculture1889–1893 |

Net worth

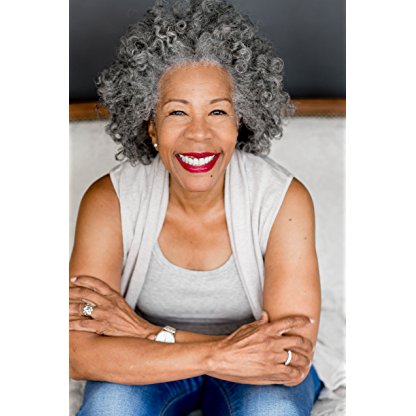

BJ Harrison, formerly an actress, is anticipated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M by the year 2024. Born in 1833, Harrison has amassed a notable fortune throughout her career, showcasing her versatility and talent on stage and potentially in other ventures. As an actress, Harrison likely garnered success and recognition, contributing to her overall net worth. With such an extensive background and the potential for future ventures, BJ Harrison continues to make a mark in the entertainment industry.

Famous Quotes:

The colored people did not intrude themselves upon us; they were brought here in chains and held in communities where they are now chiefly bound by a cruel slave code...when and under what conditions is the black man to have a free ballot? When is he in fact to have those full civil rights which have so long been his in law? When is that quality of influence which our form of government was intended to secure to the electors to be restored? … in many parts of our country where the colored population is large the people of that race are by various devices deprived of any effective exercise of their political rights and of many of their civil rights. The wrong does not expend itself upon those whose votes are suppressed. Every constituency in the Union is wronged.

Biography/Timeline

Although he had made no political bargains, his supporters had given many pledges upon his behalf. When Boss Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania, who was rebuffed for a Cabinet position for his political support during the convention, heard that Harrison ascribed his narrow victory to Providence, Quay exclaimed that Harrison would never know "how close a number of men were compelled to approach...the penitentiary to make him President." Harrison was known as the Centennial President because his inauguration celebrated the centenary of the first inauguration of George Washington in 1789. In congressional elections, the Republicans increased their membership in the House of Representatives by nineteen seats.

Harrison's paternal ancestors were the Harrison family of Virginia, whose immigrant ancestor, Benjamin Harrison, arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1630. Benjamin, the Future President, was born on August 20, 1833, in North Bend, Ohio, the second of Elizabeth Ramsey (Irwin) and John Scott Harrison's eight children. Benjamin was also a grandson of U.S. President william Henry Harrison, the first governor of the Indiana Territory, and a great-grandson of Benjamin Harrison V, a Virginia planter who signed the Declaration of Independence and succeeded Thomas Jefferson as governor of Virginia.

Benjamin Harrison's early schooling took place in a log cabin near his home, but his parents later arranged for a tutor to help him with college preparatory studies. Fourteen-year-old Harrison and his older brother, Irwin, enrolled in Farmer's College near Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1847. He attended the college for two years and while there met his Future wife, Caroline "Carrie" Lavinia Scott, a daughter of John Witherspoon Scott, the school's science professor who was also a Presbyterian minister.

In 1850, Harrison transferred to Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, and graduated in 1852. He joined the Phi Delta Theta fraternity, which he used as a network for much of his life. He was also a member of Delta Chi, a law fraternity which permitted dual membership. Classmates included John Alexander Anderson, who became a six-term U.S. congressman, and Whitelaw Reid Harrison's vice presidential running mate in 1892. At Miami, Harrison was strongly influenced by history and political economy professor Robert Hamilton Bishop. Harrison also joined a Presbyterian church at college and, like his mother, became a lifelong Presbyterian.

After his college graduation in 1852, Harrison studied law with Judge Bellamy Storer of Cincinnati, but before he completed his studies, he returned to Oxford, Ohio, to marry Caroline Scott on October 20, 1853. Caroline's father, a Presbyterian minister, performed the ceremony. The Harrisons had two children, Russell Benjamin Harrison (August 12, 1854 – December 13, 1936), and Mary "Mamie" Scott Harrison (April 3, 1858 – October 28, 1930).

Harrison and his wife, Caroline, returned to live at The Point, his father's farm in southwestern Ohio, while he finished his law studies. Harrison was admitted to the Ohio bar in early 1854, the same year he sold property that he had inherited after the death of an aunt for $800 and used the funds to move with Caroline to Indianapolis, Indiana. Harrison began practicing law in the office of John H. Ray in 1854 and became a crier for the federal court in Indianapolis, for which he was paid $2.50 per day. He also served as a Commissioner for the U.S. Court of Claims. Harrison became a founding member and first President of both the University Club, a private gentlemen's club in Indianapolis, and the Phi Delta Theta Alumni Club. Harrison and his wife became members and assumed leadership positions at Indianapolis's First Presbyterian Church.

Having grown up in a Whig household, Harrison initially favored that party's politics, but joined the Republican Party shortly after its formation in 1856 and campaigned on behalf of the Republican presidential candidate, John C. Frémont. In 1857 Harrison was elected as the Indianapolis city attorney, a position that paid an annual salary of $400.

In 1858, Harrison entered into a law partnership with william Wallace to form the law office of Wallace and Harrison. Two years later, in 1860, Harrison successfully ran as the Republican candidate for reporter of the Indiana Supreme Court. Harrison was an active supporter of the Republican Party's platform and served as Republican State Committee's secretary. After Wallace, his law partner, was elected as county clerk in 1860, Harrison established a new firm with william Fishback that was named Fishback and Harrison. The new partners worked together until Harrison entered the Union Army after the start of the American Civil War.

Morton asked Harrison if he could help recruit a regiment, although he would not ask him to serve. Harrison recruited throughout northern Indiana to raise a regiment. Morton offered him the command, but Harrison declined, as he had no military experience. He was initially commissioned as a captain and company commander on July 22, 1862. Governor Morton commissioned Harrison as a colonel on August 7, 1862, and the newly formed 70th Indiana was mustered into Federal Service on August 12, 1862. Once mustered, the regiment left Indiana to join the Union Army at Louisville, Kentucky.

While serving in the Union Army in October 1864, Harrison was once again elected reporter of the Supreme Court of Indiana, although he did not seek the position, and served as the Court's reporter for four more years. The position was unsalaried and not a politically powerful one, but it did provide Harrison with a steady income for his work preparing and publishing court opinions, which he sold to the legal profession. Harrison also resumed his law practice in Indianapolis. He became a skilled orator and known as "'one of the state's leading lawyers.'"

On January 23, 1865, President Lincoln nominated Harrison to the grade of brevet brigadier general of volunteers, to rank from that date, and the Senate confirmed the nomination on February 14, 1865. He rode in the Grand Review in Washington, D.C. before mustering out on June 8, 1865.

In 1868 President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Harrison to represent the federal government in a civil suit filed by Lambdin P. Milligan, whose controversial wartime conviction for treason in 1864 led to the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case known as Ex parte Milligan. The civil case was referred to the U.S. Circuit Court for Indiana at Indianapolis, where it evolved into Milligan v. Hovey. Although the jury rendered a verdict in Milligan's favor and he had sought hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages, state and federal statutes limited the amount the federal government had to award to Milligan to five dollars plus court costs.

With his increasing reputation, local Republicans urged Harrison to run for Congress. He initially confined his political activities to speaking on behalf of other Republican candidates, a task for which he received high praises from his colleagues. In 1872, Harrison campaigned for the Republican nomination for governor of Indiana. Former governor Oliver Morton favored his opponent, Thomas M. Browne, and Harrison lost his bid for statewide office. He returned to his law practice and, despite the Panic of 1873, he was financially successful enough to build a grand new home in Indianapolis in 1874. He continued to make speeches on behalf of Republican candidates and policies.

In 1876, when a scandal forced the original Republican nominee, Godlove Stein Orth, to drop out of the gubernatorial race, Harrison accepted the Republican Party's invitation to take his place on the ticket. Harrison centered his campaign on economic policy and favored deflating the national currency. He was ultimately defeated in a plurality by James D. Williams, losing by 5,084 votes out of a total 434,457 cast, but Harrison was able to build on his new prominence in state politics. When the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 reached Indianapolis, he gathered a citizen militia to make a show of support for owners and management, and helped to mediate an agreement between the workers and management and to prevent the strike from widening.

When United States Senator Morton died in 1878, the Republicans nominated Harrison to run for the seat, but the party failed to gain a majority in the state legislature, which at that time elected senators; the Democratic majority elected Daniel W. Voorhees instead. In 1879, President Hayes appointed Harrison to the Mississippi River Commission, which worked to develop internal improvements on the river. As a delegate to the 1880 Republican National Convention the following year, he was instrumental in breaking a deadlock on candidates, and James A. Garfield won the nomination.

Throughout the 1880s various European countries had imposed a ban on importation of United States pork out of an unconfirmed concern of trichinosis; at issue was over one billion pounds of pork products with a value of $80 million (annually). Harrison engaged Whitelaw Reid, minister to France, and william Walter Phelps, minister to Germany, to restore these exports for the country without delay. Harrison also successfully asked the congress to enact the Meat Inspection Act to eliminate the accusations of product compromise. The President also partnered with Agriculture Secretary Rusk to threaten Germany with retaliation – by initiating an embargo in the U.S. against Germany's highly demanded beet sugar. By September 1891 Germany relented, and was soon followed by Denmark, France and Austria-Hungary.

In 1881, the major issue confronting Senator Harrison was the budget surplus. Democrats wished to reduce the tariff and limit the amount of money the government took in; Republicans instead wished to spend the money on internal improvements and pensions for Civil War veterans. Harrison took his party's side and advocated for generous pensions for veterans and their widows. He also supported, unsuccessfully, aid for education of Southerners, especially the children of the freedmen; he believed that education was necessary to help the black population rise to political and economic equality with whites. Harrison opposed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which his party supported, as he thought it violated existing treaties with China.

He severely questioned the states' civil rights records, arguing that if states have the authority over civil rights, then "we have a right to ask whether they are at work upon it." Harrison also supported a bill proposed by Senator Henry W. Blair, which would have granted federal funding to schools regardless of the students' races. He also endorsed a proposed constitutional amendment to overturn the Supreme Court ruling in the Civil Rights Cases (1883) that declared much of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional. None of these measures gained congressional approval.

In 1884, Harrison and Gresham competed for influence at the 1884 Republican National Convention; the delegation ended up supporting James G. Blaine, the eventual nominee. In the Senate, Harrison achieved passage of his Dependent Pension Bill, only to see it vetoed by President Grover Cleveland. His efforts to further the admission of new western states were stymied by Democrats, who feared that the new states would elect Republicans to Congress.

In 1885 the Democrats redistricted the Indiana state legislature, which resulted in an increased Democratic majority in 1886, despite an overall Republican majority statewide. In 1887, largely as a result of the Democratic gerrymandering of Indiana's legislative districts, Harrison was defeated in his bid for reelection. Following a deadlock in the state senate, the state legislature eventually chose Democrat David Turpie as Harrison's successor in the U.S. Senate. Harrison returned to Indianapolis and resumed his law practice, but stayed active in state and national politics.

The silver coinage issue had not been much discussed in the 1888 campaign and Harrison is said to have favored a bimetallist position. However, his appointment of a silverite Treasury Secretary, william Windom, encouraged the free silver supporters. Harrison attempted to steer a middle course between the two positions, advocating a free coinage of silver, but at its own value, not at a fixed ratio to gold. This failed to facilitate a compromise between the factions. In July 1890, Senator Sherman achieved passage of a bill, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, in both houses. Harrison thought that the bill would end the controversy, and he signed it into law. The effect of the bill, however, was the increased depletion of the nation's gold supply, a Problem that would persist until the second Cleveland administration resolved it.

Harrison attended a grand, three-day centennial celebration of George Washington's inauguration in New York City on April 30, 1889, and made the following remarks "We have come into the serious but always inspiring presence of Washington. He was the incarnation of duty and he teaches us today this great lesson: that those who would associate their names with events that shall outlive a century can only do so by high consecration to duty. Self-seeking has no public observance or anniversary."

During the hot Washington summers, the Harrisons took refuge in Deer Park, Maryland and Cape May Point, New Jersey. In 1890, John Wanamaker joined with other Philadelphia devotees of the Harrisons and made a gift to them of a summer cottage at Cape May. Harrison, though appreciative, was uncomfortable with the appearance of impropriety; a month later, he paid Wanamaker $10,000 as reimbursement to the donors. Nevertheless, Harrison's opponents made the gift the subject of national ridicule, and Mrs. Harrison and the President were vigorously criticized.

In 1891, a diplomatic crisis emerged in Chile, otherwise known as the Baltimore Crisis. The American minister to Chile, Patrick Egan, granted asylum to Chileans who were seeking refuge during the 1891 Chilean Civil War. Egan, previously a militant Irish immigrant to the U.S., was motivated by a personal Desire to thwart Great Britain's influence in Chile; his action increased tensions between Chile and the United States, which began in the early 1880s when Secretary Blaine had alienated the Chileans in the War of the Pacific.

Harrison's wife Caroline began a critical struggle with tuberculosis earlier in 1892, and two weeks before the election, on October 25, it took her life. Their daughter Mary Harrison McKee assumed the role of First Lady after her mother's death. Mrs. Harrison's terminal illness and the fact that both candidates had served in the White House called for a low key campaign, and resulted in neither of the candidates actively campaigning personally.

Following the Panic of 1893, Harrison became more popular in retirement. His legacy among historians is scant, and "general accounts of his period inaccurately treat Harrison as a cipher". More recently,

From July 1895 to March 1901 Harrison served on the Board of Trustees of Purdue University, where Harrison Hall, a dormitory, was named in his honor. He wrote a series of articles about the federal government and the presidency which were republished in 1897 as a book titled This Country of Ours. In 1896, Harrison at age 62 remarried, to Mary Scott Lord Dimmick, the widowed 37-year-old niece and former secretary of his deceased wife. Harrison's two adult children, Russell, 41 years old at the time, and Mary (Mamie) McKee, 38, disapproved of the marriage and did not attend the wedding. Benjamin and Mary had one child together, Elizabeth (February 21, 1897 – December 26, 1955).

In 1898, Harrison served as an attorney for the Republic of Venezuela in their British Guiana boundary dispute with the United Kingdom. An international trial was agreed upon; he filed an 800-page brief and traveled to Paris where he spent more than 25 hours in court on Venezuela's behalf. Although he lost the case, his legal arguments won him international renown. In 1899 Harrison attended the First Peace Conference at The Hague.

Harrison developed what was thought to be influenza (then referred to as grippe) in February 1901. He was treated with steam vapor inhalation and oxygen, but his condition worsened. He died from pneumonia at his home in Indianapolis on Wednesday, March 13, 1901, at the age of 67. Harrison's remains are interred in Indianapolis's Crown Hill Cemetery, next to the remains of his first wife, Caroline. After her death in 1948, Mary Dimmick Harrison, his second wife, was buried beside him.

Harrison was memorialized on several postage stamps. The first was a 13-cent stamp issued on November 18, 1902, with the engraved likeness of Harrison modeled after a photo provided by his widow. In all Harrison has been honored on six U.S. Postage stamps, more than most other U.S. Presidents. Harrison also was featured on the five-dollar National Bank Notes from the third charter period, beginning in 1902. In 2012, a dollar coin with his image, part of the Presidential $1 Coin Program, was issued.

Theodore Roosevelt dedicated Fort Benjamin Harrison in the former president's honor in 1906. It is located in Lawrence, Indiana, a northeastern suburb of Indianapolis. The federal government decommissioned Fort Harrison in 1991 and transferred 1,700 of its 2,500 acres to Indiana's state government in 1995 to establish Fort Harrison State Park. The site has been redeveloped to include residential neighborhoods and a golf course.

In 1908, the people of Indianapolis erected the Benjamin Harrison memorial statue, created by Charles Niehaus and Henry Bacon, in honor of Harrison's lifetime achievements as military leader, U.S. Senator, and President of the United States. The statue occupies a site on the south edge of University Park, facing the Birch Bayh Federal Building and United States Courthouse across New York Avenue.

Harrison's presidency belongs properly to the 19th century, but he "clearly pointed the way" to the modern presidency that would emerge under william McKinley. The bi-partisan Sherman Anti-Trust Act signed into law by Harrison remains in effect over 120 years later and was the most important legislation passed by the Fifty-first Congress. Harrison's support for African American voting rights and education would be the last significant attempts to protect civil rights until the 1930s. Harrison's tenacity at foreign policy was emulated by politicians such as Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1942, a Liberty Ship, the SS Benjamin Harrison, was named in his honor. In 1951, Harrison's home was opened to the public as a library and museum. It had been used as a dormitory for a music school from 1937 to 1950. The house was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1964.

Members of both parties were concerned with the growth of the power of trusts and monopolies, and one of the first acts of the 51st Congress was to pass the Sherman Antitrust Act, sponsored by Senator John Sherman of Ohio. The Act passed by wide margins in both houses, and Harrison signed it into law. The Sherman Act was the first Federal act of its kind, and marked a new use of federal government power. While Harrison approved of the law and its intent, his administration was not particularly vigorous in enforcing it. However, the government successfully concluded a case during Harrison's time in office (against a Tennessee coal company), and had initiated several other cases against trusts.

The treasury surplus had evaporated and the nation's economic health was worsening – precursors to the eventual Panic of 1893. Congressional elections in 1890 had gone against the Republicans; and although Harrison had cooperated with Congressional Republicans on legislation, several party Leaders withdrew their support for him because of his Adam Ant refusal to give party members the nod in the course of his executive appointments. Specifically, Thomas C. Platt, Matthew S. Quay, Thomas B. Reed and James Clarkson quietly organized the Grievance Committee, the ambition of which was to initiate a dump-Harrison offensive. They solicited the support of Blaine, without effect however, and Harrison in reaction resolved to run for re-election – seemingly forced to choose one of two options – "become a candidate or forever wear the name of a political coward".

According to Historian R. Hal Williams, Harrison had a "widespread reputation for personal and official integrity". Closely scrutinized by Democrats, Harrison's reputation was largely intact when he left the White House. Having an advantage few 19th Century Presidents had, Harrison's own party, the Republicans, controlled Congress, while his administration actively advanced a Republican program of a higher tariff, moderate control of corporations, protecting African American voting rights, a generous Civil War pension, and compromising over the controversial silver issue. Historians have not raised "serious questions about Harrison's own integrity or the integrity of his administration."