Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Nez Perce leader |

| Birth Day | March 03, 1840 |

| Birth Place | Wallowa River, United States |

| Age | 179 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | September 21, 1904(1904-09-21) (aged 64)\nColville Indian Reservation, Washington, United States |

| Birth Sign | Aries |

| Native name | Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it |

| Cause of death | heart failure |

| Resting place | Chief Joseph Cemetery Nespelem, Washington 48°10′6.72″N 118°58′37.69″W / 48.1685333°N 118.9771361°W / 48.1685333; -118.9771361Coordinates: 48°10′6.72″N 118°58′37.69″W / 48.1685333°N 118.9771361°W / 48.1685333; -118.9771361 |

| Other names | Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt Chief Joseph Joseph the Younger Young Joseph The Red Napoleon |

| Known for | Nez Perce leader |

| Predecessor | Joseph the Elder (father) |

| Spouse(s) | Heyoon Yoyikt Springtime |

| Children | Jean-Louise (daughter) |

| Parent(s) | Tuekakas (father) Khapkhaponimi (mother) |

| Relatives | Sousouquee (older brother), Ollokot (younger brother), four sisters |

Net worth

Chief Joseph, the esteemed Nez Perce leader in the United States, is projected to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million by the year 2024. Recognized for his valiant efforts in fighting for Native American rights and leading his tribe through tumultuous times, Chief Joseph's legacy reverberates to this day. Despite the financial limitations imposed upon Native American tribes, Chief Joseph's net worth symbolizes his enduring influence and the timeless significance of his leadership in preserving the Nez Perce culture and heritage.

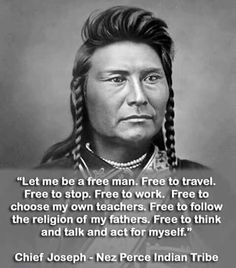

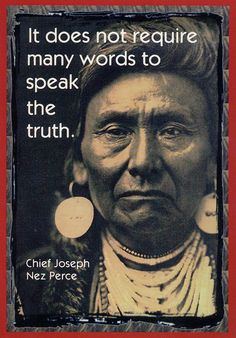

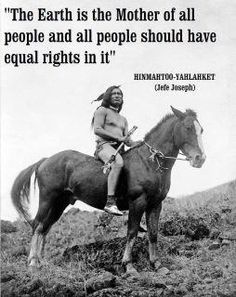

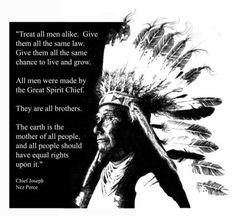

Famous Quotes:

My son, my body is returning to my mother earth, and my spirit is going very soon to see the Great Spirit Chief. When I am gone, think of your country. You are the chief of these people. They look to you to guide them. Always remember that your father never sold his country. You must stop your ears whenever you are asked to sign a treaty selling your home. A few years more and white men will be all around you. They have their eyes on this land. My son, never forget my dying words. This country holds your father's body. Never sell the bones of your father and your mother.

Biography/Timeline

While initially hospitable to the region's newcomers, Joseph the Elder grew wary when white settlers demanded more Indian lands. Tensions grew as the settlers appropriated traditional Indian lands for farming and grazing livestock. Isaac Stevens, governor of the Washington Territory, organized a council to designate separate areas for natives and settlers in 1855. Joseph the Elder and the other Nez Perce chiefs signed the Treaty of Walla Walla, with the United States establishing a Nez Perce reservation encompassing 7,700,000 acres (31,000 km) in present-day Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. The 1855 reservation maintained much of the traditional Nez Perce lands, including Joseph's Wallowa Valley. It is recorded that the elder Joseph requested that Young Joseph protect their 7.7-million-acre homeland, and guard his father's burial place.

Joseph the Younger succeeded his father as leader of the Wallowa band in 1871. Before his death, the latter counseled his son:

The non-treaty Nez Perce suffered many injustices at the hands of settlers and prospectors, but out of fear of reprisal from the militarily superior Americans, Joseph never allowed any violence against them, instead making many concessions to them in the hope of securing peace. A handwritten document mentioned in the Oral History of the Grande Ronde recounts an 1872 experience by Oregon pioneer Henry Young and two friends in search of acreage at Prairie Creek, east of Wallowa Lake. Young's party was surrounded by 40–50 Nez Perce led by Chief Joseph. The Chief told Young that white men were not welcome near Prairie Creek, and Young's party was forced to leave without violence.

In 1873, Joseph negotiated with the federal government to ensure his people could stay on their land in the Wallowa Valley. But in 1877, the government reversed its policy, and Army General Oliver O. Howard threatened to attack if the Wallowa band did not relocate to the Idaho reservation with the other Nez Perce. Joseph reluctantly agreed. Before the outbreak of hostilities, General Howard held a council at Fort Lapwai to try to convince Joseph and his people to relocate. Joseph finished his address to the general, which focused on human equality, by expressing his "[disbelief that] the Great Spirit Chief gave one kind of men the right to tell another kind of men what they must do." Howard reacted angrily, interpreting the statement as a challenge to his authority. When Toohoolhoolzote protested, he was jailed for five days.

The U.S. Army's pursuit of about 750 Nez Perce and a small allied band of the Palouse tribe, led by Chief Joseph and others, as they attempted to escape from Idaho became known as the Nez Perce War. Initially they had hoped to take refuge with the Crow Nation in the Montana Territory, but when the Crow refused to grant them aid, the Nez Perce went north in an attempt to obtain asylum with the Lakota band led by Sitting Bull, who had fled to Canada following the Great Sioux War in 1876. In Hear Me, My Chiefs!: Nez Perce Legend and History, Lucullus V. McWhorter argues that the Nez Perce were a peaceful people that were forced into war by the United States when their land was stolen from them. McWhorter interviewed and befriended Nez Perce warriors such as Yellow Wolf, who stated, “Our hearts have always been in the valley of the Wallowa”.

Although Joseph was not technically a war chief and probably did not command the retreat, many of the chiefs who did had died. His speech brought attention, and therefore credit, his way. He earned the praise of General william Tecumseh Sherman and became known in the press as "The Red Napoleon". However, as Francis Haines argues in Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce Warrior, the battlefield successes of the Nez Perce during the war were due to the individual successes of the Nez Perce men and not that of the fabled military genius of Chief Joseph. Haines supports his argument by citing L.V. McWhorter, who concluded “that Chief Joseph was not a military man at all, that on the battlefield he was without either skill or experience". Furthermore, Merle Wells argues in The Nez Perce and Their War that the interpretation of the Nez Perce War of 1877 in military terms as used in the United States Army’s account distorts the actions of the Nez Perce. Wells supports his argument: “The use of military concepts and terms is appropriate when explaining what the whites were doing, but these same military terms should be avoided when referring to Indian actions; the United States use of military terms such as “retreat” and “surrender” has created a distorted perception of the Nez Perce War, to understand this may lend clarity to the political and military victories of the Nez Perce."

In 1879, Chief Joseph went to Washington, D.C. to meet with President Rutherford B. Hayes and plead his people's case. Although Joseph was respected as a spokesman, opposition in Idaho prevented the U.S. government from granting his petition to return to the Pacific North West. Finally, in 1885, Chief Joseph and his followers were granted permission to return to the Pacific North West to settle on the reservation around Kooskia, Idaho. Instead, Joseph and others were taken to the Colville Indian Reservation in Nespelem, Washington, far from both their homeland in the Wallowa Valley and the rest of their people in Idaho.

In his last years, Joseph spoke eloquently against the injustice of United States policy toward his people and held out the hope that America's promise of freedom and equality might one day be fulfilled for Native Americans as well. In 1897, he visited Washington, D.C. again to plead his case. He rode with Buffalo Bill Cody in a parade honoring former President Ulysses Grant in New York City, but he was a topic of conversation for his traditional headdress more than his mission.

In 1903, Chief Joseph visited Seattle, a booming young town, where he stayed in the Lincoln Hotel as guest to Edmond Meany, a history professor at the University of Washington. It was there that he also befriended Edward Curtis, the Photographer, who took one of his most memorable and well-known photographs. Joseph also visited President Theodore Roosevelt in Washington, D.C. the same year. Everywhere he went, it was to make a plea for what remained of his people to be returned to their home in the Wallowa Valley, but it never happened.

An indomitable voice of conscience for the West, in September 1904, still in exile from his homeland, Chief Joseph died, according to his Doctor, "of a broken heart". Meany and Curtis helped Joseph's family bury their chief near the village of Nespelem, Washington.

In July 2012, Chief Joseph's 1870s war shirt was sold to a private collection for the sum of $877,500.