Age, Biography and Wiki

| Birth Year | 1786 |

| Birth Place | Blake Island, United States |

| Age | 233 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | (1866-06-07)June 7, 1866\nPort Madison, Washington, U.S. |

| Resting place | Port Madison, Washington, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) | Ladaila, Owiyahl |

| Relations | Doc Maynard |

| Children | 88, including Princess Angeline |

| Parents | Sholeetsa (Mother), Shweabe (Father) |

| Known for | Namesake of city of Seattle |

Net worth: $6 Million (2024)

Chief Seattle was a prominent political leader in the United States, known for his influential role in advocating for the rights of Native American tribes. In 2024, his estimated net worth reached an astounding $6 million. This impressive fortune reflects his successful endeavors in safeguarding the interests of his people and creating awareness about the historical and cultural significance of Native American communities. Chief Seattle's net worth not only underscores his financial achievements but also serves as a testament to his enduring legacy as an influential figure in American history.

Famous Quotes:

"I first heard a version of the text read by William Arrowsmith at the first Environmental Day celebration in 1970. I was there and heard him. He was a close friend. Arrowsmith's version hinted at how difficult it was for Seattle to understand the white man's attitude toward land, water, air, and animals. For the soundtrack for a documentary I had already proposed about the environment, I decided to write a new version, elaborating on and heightening what was hinted at in Arrowsmith's text ... While it would be easy to hide behind the producer's decision, without my permission, to delete my "Written by" credit when the film was finished and aired on television, the real problem is that I should not have used the name of an actual human being, Chief Seattle. That I could put words into the mouth of someone I did not know, particularly a Native American, is pure hubris if not racist. While there has been some progress in our knowledge of Native Americans, we really know very little. What we think we know is mediated by films, chance encounters, words, images and other stereotypes. They serve our worldview but they are not true."

Biography/Timeline

Seattle's mother Sholeetsa was Dkhw'Duw'Absh (Duwamish) and his father Shweabe was chief of the Dkhw'Suqw'Absh (the Suquamish tribe). Seattle was born some time between 1780 and 1786 on or near Blake Island, Washington. One source cites his mother's name as Wood-sho-lit-sa. The Duwamish tradition is that Seattle was born at his mother's village of Stuk on the Black River, in what is now the city of Kent, Washington, and that Seattle grew up speaking both the Duwamish and Suquamish dialects of Lushootseed. Because Native descent among the Salish peoples was not solely patrilineal, Seattle inherited his position as chief of the Duwamish Tribe from his maternal uncle.

Seattle earned his reputation at a young age as a leader and a warrior, ambushing and defeating groups of tribal enemy raiders coming up the Green River from the Cascade foothills. In 1847 he helped lead a Suquamish attack upon the Chimakum people near Port Townsend, which effectively wiped out the Chimakum.

Chief Seattle took wives from the village of Tola'ltu just southeast of Duwamish Head on Elliott Bay (now part of West Seattle). His first wife La-Dalia died after bearing a daughter. He had three sons and four daughters with his second wife, Olahl. The most famous of his children was his first, Kikisoblu or Princess Angeline. Seattle was converted to Christianity by French missionaries, and was baptized in the Roman Catholic Church, with the baptismal name Noah, probably in 1848 near Olympia, Washington.

For all his skill, Seattle was gradually losing ground to the more powerful Patkanim of the Snohomish when white settlers started showing up in force around 1850. (In later years, Seattle claimed to have seen the ships of the Vancouver Expedition as they explored Puget Sound in 1792.) When his people were driven from their traditional clamming grounds, Seattle met Doc Maynard in Olympia; they formed a friendly relationship useful to both. Persuading the settlers at the white settlement of Duwamps to rename their town Seattle, Maynard established their support for Chief Seattle's people and negotiated relatively peaceful relations with the tribes.

However the date, the location, and the actual words of Chief Seattle's speech are disputed. For instance, Smith's article in the Seattle Sunday Star claims that the purpose of Governor Stevens's meeting was to discuss the surrender or sale of the Indians' land to white settlers — but there is no record to support that this was the purpose of Stevens's visit; in fact, the purpose of the visit seems to have been to investigate lands already considered to belong to the United States. Moreover, contemporary witnesses do not place Smith at the 1854 meeting. There is a written record of a later meeting between Governor Stevens and Chief Seattle, taken by government interpreters at the Point Elliott Treaty signing on January 22, 1855. But the proceedings of this meeting bear no resemblance to the reminiscence that Dr. Smith recorded in 1887.

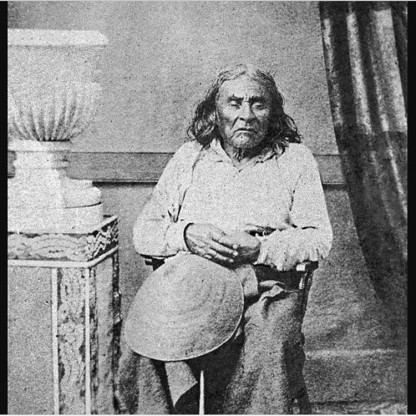

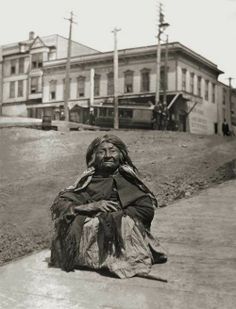

Seattle kept his people out of the Battle of Seattle in 1856. Afterwards, he was unwilling to lead his tribe to the reservation established, since mixing Duwamish and Snohomish was likely to lead to bloodshed. Maynard persuaded the government of the necessity of allowing Seattle to remove to his father's longhouse on Agate Passage, 'Old Man House' or Tsu-suc-cub. Seattle frequented the town named after him, and had his photograph taken by E. M. Sammis in 1865. He died June 7, 1866, on the Suquamish reservation at Port Madison, Washington.

However, a spokesperson for the Suquamish Nation has said that according to their traditions, Dr. Smith consulted the tribal elders numerous times before publishing his transcript of the speech in 1887. The elders apparently saw the notes Dr. Smith took while listening to the speech. The elders' approval of Smith's transcript, if real, would give that version the status of an authentic version. Smith's notes are no longer extant. They may have been lost in the Great Seattle Fire, when Smith's office burned down.

The first few subsequent versions can be briefly enumerated: in 1891, Frederick James Grant's History of Seattle, Washington reprinted Smith's version. In 1929, Clarence B. Bagley's History of King County, Washington reprinted Grant's version with some additions. In 1931, Roberta Frye Watt reprinted Bagley's version in her memoir, Four Wagons West. That same year, John M. Rich used the Bagley text in a popular pamphlet, Chief Seattle's Unanswered Challenge.

In the late 1960s, a new era dawned in the fame of the speech and in its further modification. This began with a series of articles by william Arrowsmith, a professor at the University of Texas, which revived interest in Seattle's speech. Arrowsmith had come across the speech in a collection of essays by the President of Washington State University. At the end of one of the essays, there were some quotes from Smith's version of Chief Seattle's speech. Arrowsmith said it read like prose from the Greek poet Pindar. With interest aroused, he found the original source. After reading it, he decided to try improving Smith's version of the speech, by removing Victorian influences. Arrowsmith attempted to get a sense of how Chief Seattle might have spoken, and to establish some "likely perimeters of the language."

The version of Chief Seattle's speech edited by Stevens was then made into a poster and 18,000 copies were sent out as a promotion for the movie. The movie itself sank without a trace, but this newest and most fictional version of Chief Seattle's speech became the most widely known, as it became disseminated within the Environmentalist movement of the 1970s — now in the form of a "letter to the President" (see below).

A similar controversy surrounds a purported 1855 letter from Seattle to President Franklin Pierce, which has never been located and, based on internal evidence, is described by Historian Jerry L. Clark as "an unhistorical artifact of someone's fertile literary imagination". It seems that the "letter" surfaced within Environmentalist literature in the 1970s, as a slightly altered form of the Perry/Stevens version. The first environmental version was published in the November 11, 1972 issue of Environmental Action magazine. By this time it was no longer billed as a speech, but as a letter from Chief Seattle to President Pierce. The Editor of Environmental Action had picked it up from Dale Jones, who was the North West Representative of the group Friends of the Earth. Jones himself has since said that he "first saw the letter in September 1972 in a now out of Business Native American tabloid newspaper." Here all leads end, but it is safe to assume the original source was the movie poster.

The evolution of the text of Chief Seattle's speech, from a flowery Victorian paean to peace and territorial integrity, into a much briefer Environmentalist credo, has been chronicled by several historians. The first attempt to reconstruct this history was a 1985 essay in the U.S. National Archives' Prologue magazine. A more scholarly essay by a German Anthropologist followed in 1987. In 1989, a radio documentary by Daniel and Patricia Miller resulted in the uncovering of no fewer than 86 versions of Chief Seattle's speech. This then prompted a new discussion, first in the Seattle Weekly and then in Newsweek. The Historian Albert Furtwangler then undertook to analyze the evolution of Chief Seattle's speech in a full-length book, Answering Chief Seattle (1997). More recently, Eli Gifford has written another full-length book, The Many Speeches of Chief Seattle (2015), which assembles further elements of the story, gives accurate transcriptions of 11 versions of the speech, and explores possible motivations for manipulating the words in each case.

In 1993 Nancy Zussy, a librarian at Washington State University, analyzed the versions of Chief Seattle's speech (or "letter") which were then in circulation. She identified four major textual variants, which she ascribed to four authors as follows:

It would be quite improbable if not impossible for a letter from the Chief of an Indian tribe to the President of the United States not to have been recorded in at least one of the governmental offices through which it passed. For the letter to have made it to the desk of the President it would have passed through at least six departments: the local Indian agent, Colonel Simmons; to the superintendent of Indian Affairs, Gov. Stevens; to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs; to the office of the Secretary of the Interior and finally to the President's desk—quite a paper trail for the letter to have left not a trace. It can be concluded that no letter was written by or for Seattle and sent to President Pierce or to any other President. (Seattle was illiterate and moreover did not speak English, so he obviously could not write English.)