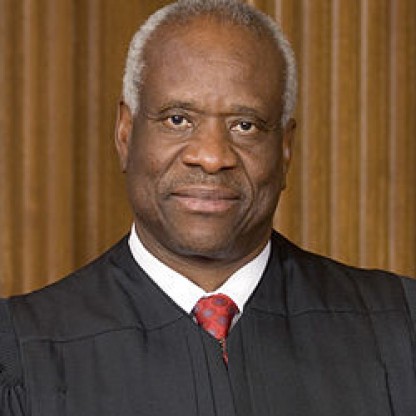

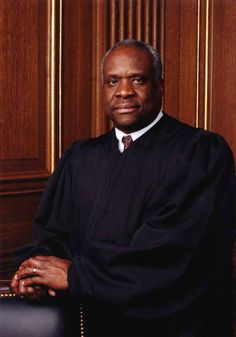

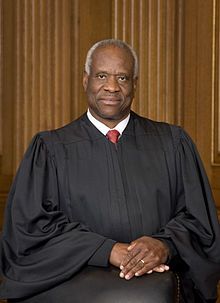

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States |

| Birth Day | June 23, 1948 |

| Birth Place | Pin Point, Georgia, U.S., United States |

| Age | 75 YEARS OLD |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

| Nominated by | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Cynthia Brown |

| Succeeded by | Harry Singleton |

| President | Ronald Reagan |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Kathy Ambush (m. 1971; div. 1984) Virginia Lamp (m. 1987) |

| Children | 1 |

| Education | Conception Seminary College College of the Holy Cross (BA) Yale University (JD) |

Net worth: $4.2 Million (2024)

Clarence Thomas, well known as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, is estimated to have a net worth of $4.2 million as of 2024. As one of the most influential figures in the American legal system, Thomas has dedicated his career to upholding the Constitution and interpreting the law. Serving on the Supreme Court since 1991, his decisions have played a significant role in shaping legal precedents in the United States. Despite his notable position, Thomas' net worth remains relatively moderate compared to some of his peers, reflecting his commitment to public service and the judiciary's impartiality.

Famous Quotes:

I peeled a fifteen-cent sticker off a package of cigars and stuck it on the frame of my law degree to remind myself of the mistake I'd made by going to Yale. I never did change my mind about its value.

Biography/Timeline

Clarence Thomas was born in 1948 in Pin Point, Georgia, a small, predominantly black community near Savannah founded by freedmen after the American Civil War. He was the second of three children born to M.C. Thomas, a farm worker, and Leola Williams, a domestic worker. They were descendants of American slaves, and the family spoke Gullah as a first language. Thomas's earliest-known ancestors were slaves named Sandy and Peggy who were born around the end of the 18th century and owned by wealthy Liberty County, Georgia, planter Josiah Wilson. M.C. left his family when Thomas was two years old. Thomas's mother worked hard but was sometimes paid only pennies per day. She had difficulty putting food on the table and was forced to rely on charity. After a house fire left them homeless, Thomas and his younger brother Myers were taken to live with his maternal grandparents in Savannah, Georgia. Thomas was seven when the family moved in with his maternal grandfather, Myers Anderson, and Anderson's wife, Christine (née Hargrove), in Savannah.

Thomas has recollected that his Yale law degree was not taken seriously by law firms to which he applied after graduating. He said that potential employers assumed he obtained it because of affirmative action policies. (In 1969 Dean Louis Pollak wrote that the law school was expanding its program of quotas for black applicants, with up to 24 entering that year admitted under a system that deemphasized grades and LSAT scores.) According to Thomas, he was "asked pointed questions, unsubtly suggesting that they doubted I was as smart as my grades indicated."

Thomas is not the first quiet justice. In the 1970s and 1980s, william J. Brennan, Thurgood Marshall, and Harry Blackmun generally were quiet; however, the silence of Thomas stood out in the 1990s as the other eight justices engaged in active questioning. The New York Times' Supreme Court correspondent Adam Liptak has called it a "pity" that Thomas does not ask questions, saying that he has a "distinctive legal philosophy and a background entirely different from that of any other justice" and that those he asked in the 2001 and 2002 terms were "mostly good questions, brisk and pointed." Conversely, Jeffrey Toobin, writing in The New Yorker, calls the silence of Thomas "disgraceful" behaviour that has "gone from curious to bizarre to downright embarrassing, for himself and for the institution he represents".

In 1971, Thomas married his college sweetheart, Kathy Grace Ambush. They had one child, Jamal Adeen. In 1981 they separated and they divorced in 1984. In 1987, Thomas married Virginia Lamp, a lobbyist and aide to Republican Congressman Dick Armey. In 1997, they took in Thomas's then six-year-old great nephew, Mark Martin Jr., who had lived with his mother in Savannah public housing.

Thomas was admitted to the Missouri bar on September 13, 1974. From 1974 to 1977, Thomas was an Assistant Attorney General of Missouri under State Attorney General John Danforth, who met Thomas at Yale Law School. Thomas was the only black member of Danforth's staff. As Assistant Attorney General, Thomas first worked at the Criminal appeals division of Danforth's office and moved on to the revenue and taxation division. Retrospectively, Thomas considers Assistant Attorney General the best job he has ever had. When Danforth was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1976, Thomas left to become an attorney with the Monsanto Chemical Company in St. Louis, Missouri. He moved to Washington, D.C. and returned to work for Danforth from 1979 to 1981 as a Legislative Assistant handling Energy issues for the Senate Commerce Committee. The two men shared a Common bond in that they had studied to be ordained (although in different denominations). Danforth was to be instrumental in championing Thomas for the Supreme Court.

In 1975, when Thomas read Race and Economics by Economist Thomas Sowell, he found an intellectual foundation for his philosophy. The book criticized social reforms by government and instead argued for individual action to overcome circumstances and adversity. He was also influenced by Ayn Rand, particularly The Fountainhead, and would later require his staffers to watch the 1949 film version. Thomas later said that Novelist Richard Wright had been the most influential Writer in his life; Wright's books Native Son and Black Boy "capture[d] a lot of the feelings that I had inside that you learn how to repress." Thomas acknowledges having "some very strong libertarian leanings".

Regarding capital punishment, Thomas was among the dissenters in Atkins v. Virginia and Roper v. Simmons, which held that the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the application of the death penalty to certain classes of persons. In Kansas v. Marsh, his opinion for the court indicated a belief that the constitution affords states broad procedural latitude in imposing the death penalty, provided they remain within the limits of Furman v. Georgia and Gregg v. Georgia, the 1976 case in which the court had reversed its 1972 ban on death sentences if states followed procedural guidelines.

In Doggett v. United States, the defendant had technically been a fugitive from the time he was indicted in 1980 until his arrest in 1988. The court held that the delay between indictment and arrest violated Doggett's Sixth Amendment right to a speedy trial, finding that the government had been negligent in pursuing him and that he was unaware of the indictment. Thomas dissented, arguing that the purpose of the Speedy Trial Clause was to prevent "'undue and oppressive incarceration' and the 'anxiety and concern accompanying public accusation'" and that the case implicated neither. He cast the case instead as, "present[ing] the question [of] whether, independent of these core concerns, the Speedy Trial Clause protects an accused from two additional harms: (1) prejudice to his ability to defend himself caused by the passage of time; and (2) disruption of his life years after the alleged commission of his crime." Thomas dissented from the court's decision to, as he saw it, answer the former in the affirmative. Thomas wrote that dismissing the conviction "invites the Nation's judges to indulge in ad hoc and result-driven second guessing of the government's investigatory efforts. Our Constitution neither contemplates nor tolerates such a role."

In 1981, he joined the Reagan administration. From 1981 to 1982, he served as Assistant Secretary of Education for the Office for Civil Rights in the U.S. Department of Education. From 1982 to 1990, he was Chairman of the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ("EEOC"). Journalist Evan Thomas characterized Thomas as "openly ambitious for higher office" during his tenure at the EEOC. As Chairman, he promoted a doctrine of self-reliance, and halted the usual EEOC approach of filing class-action discrimination lawsuits, instead pursuing acts of individual discrimination. He also asserted in 1984 that black Leaders were "watching the destruction of our race" as they "bitch, bitch, bitch" about President Reagan instead of working with the Reagan administration to alleviate teenage pregnancy, unemployment and illiteracy.

On October 30, 1989, Thomas was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit vacated by Robert Bork, despite Thomas's initial protestations that he would not like to be a judge. Thomas gained the support of other African Americans such as former Transportation Secretary william Coleman, but said that when meeting white Democratic staffers in the United States Senate, he was "struck by how easy it had become for sanctimonious whites to accuse a black man of not caring about civil rights."

Thomas was reconciled to the Catholic Church in the mid-1990s. In his 2007 autobiography, he criticized the church for its failure to grapple with racism in the 1960s during the civil rights movement, saying it was not so "adamant about ending racism then as it is about ending abortion now". Thomas is one of thirteen Catholic justices—out of 112 justices total—in the history of the Supreme Court, and one of five currently on the court.

According to the Oyez Project, there was a lack of convincing proof produced at the Senate hearings. After extensive debate, the Judiciary Committee split 7–7 on September 27, sending the nomination to the full Senate without a recommendation. Thomas was confirmed by a 52–48 vote on October 15, 1991, the narrowest margin for approval in more than a century. The final floor vote was: 41 Republicans and 11 Democrats voted to confirm while 46 Democrats and two Republicans voted to reject the nomination.

Thomas has contended that the Constitution does not address the issue of abortion. In Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), the court reaffirmed Roe v. Wade. Thomas along with Justice Byron White joined the dissenting opinions of Chief Justice william Rehnquist and Justice Antonin Scalia. Rehnquist wrote that "[w]e believe Roe was wrongly decided, and that it can and should be overruled consistently with our traditional approach to stare decisis in constitutional cases." Scalia's opinion concluded that the right to obtain an abortion is not "a liberty protected by the Constitution of the United States." "[T]he Constitution says absolutely nothing about it," Scalia wrote, "and [ ] the longstanding traditions of American society have permitted it to be legally proscribed."

Law professor Amy Barrett maintains that Thomas supports statutory stare decisis. Her cited examples include Thomas's concurring opinion in Fogerty v. Fantasy, 510 U.S. 517 (1994).

In Gratz v. Bollinger, Thomas said that, in his view, "a State's use of racial discrimination in higher education admissions is categorically prohibited by the Equal Protection Clause." In Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, Thomas joined the opinion of Chief Justice Roberts, who concluded that "[t]he way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race." Concurring, Thomas wrote that "if our history has taught us anything, it has taught us to beware of elites bearing racial theories," and charged that the dissent carried "similarities" to the arguments of the segregationist litigants in Brown v. Board of Education. In Grutter v. Bollinger, he approvingly quoted Justice Harlan's Plessy v. Ferguson dissent: "Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens." In a concurrence in Missouri v. Jenkins (1995), he wrote that the Missouri District Court "has read our cases to support the theory that black students suffer an unspecified psychological harm from segregation that retards their mental and educational development. This approach not only relies upon questionable social science research rather than constitutional principle, but it also rests on an assumption of black inferiority."

In Romer v. Evans (1996), Thomas joined Scalia's dissenting opinion arguing that Amendment Two to the Colorado State Constitution did not violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Colorado amendment forbade any judicial, legislative, or executive action designed to protect persons from discrimination based on "homosexual, lesbian, or bisexual orientation, conduct, practices or relationships."

In 2000, he told a group of high school students that "if you wait long enough, someone will ask your question." Although he rarely speaks from the bench, Thomas has acknowledged that sometimes, during oral arguments, he will pass notes to his friend and colleague Justice Stephen Breyer, who then asks questions on behalf of Thomas.

Among the nine justices, Thomas was the second most likely to uphold free speech claims (tied with David Souter), as of 2002. He has voted in favor of First Amendment claims in cases involving a wide variety of issues, including pornography, campaign contributions, political leafleting, religious speech, and commercial speech.

In Lawrence v. Texas (2003), Thomas issued a one-page dissent where he favorably quoted a lawmaker who called the Texas anti-gay sodomy statute "uncommonly silly." He then said that if he were a member of the Texas legislature he would vote to repeal the law, as it was not a worthwhile use of "law enforcement resources" to police private sexual behavior. However, Thomas opined that the Constitution did not contain a right to privacy; therefore, he did not vote to strike the statute down. Accordingly, Thomas saw the issue as a matter for the states to decide for themselves.

In a line of cases beginning with Crawford v. Washington, decided in 2004, Thomas has joined with Justice Scalia and several liberals on the court in reasserting the importance of the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment, by declaring testimonial statements inadmissible at trial unless the witness is unavailable and there has been ample opportunity for cross-examination; however, his decisions in these cases had not always aligned with Scalia's. In his concurring opinion in the 2011 case Michigan v. Bryant, for Example, Thomas explains that in deciding whether a statement is testimonial, one must consider the formality of the circumstances in which it was given.

Thomas is well known for his reticence during oral argument. Beginning when he asked a question during a death penalty case on February 22, 2006, Thomas had not asked another question from the bench for more than ten years, finally asking a question on February 29, 2016, about a response to a question regarding whether persons convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence should be barred permanently from firearm possession. He also had a nearly seven-year streak of not speaking at all in any context, finally breaking that silence on January 14, 2013, when he was understood to have joked that a law degree from Yale may be proof of incompetence.

In November 2007, Thomas told an audience at Hillsdale College: "My colleagues should shut up!" He later explained, "I don't think that for judging, and for what we are doing, all those questions are necessary." According to Amber Porter of ABC News, one of the most notable examples of a rare instance in which Thomas asked a question was in 2002 during oral arguments for Virginia v. Black, when he expressed concern to Michael Dreeben, who had been speaking on behalf of the U.S. Department of Justice, that he was "actually understating the symbolism... and the effect of... the burning cross" and its use as a symbol of the "reign of terror" of "100 years of lynching and activity in the South by the Knights of Camellia... and the Ku Klux Klan".

Thomas voted with the majority in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), which held that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to firearm ownership.

In the 2009 Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. 1 v. Holder case, Thomas was the sole dissenter, voting in favor of throwing out Section Five of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Section Five requires states with a history of racial voter discrimination—mostly states from the old South—to get Justice Department clearance when revising election procedures. Although congress had reauthorized Section Five in 2006 for another 25 years, Thomas said the law was no longer necessary, pointing out that the rate of black voting in seven Section Five states was higher than the national average. Thomas said "the violence, intimidation and subterfuge that led Congress to pass Section 5 and this court to uphold it no longer remains." He again took this position in Shelby County v. Holder, voting with the majority and concurring with the reasoning which struck down Section Five.

Since 2010, Thomas has strongly dissented from denial of certiorari in Second Amendment cases that he contends were wrongly decided by various Circuit Courts of Appeals. He would have voted to grant certiorari in Friedman v. City of Highland Park (2015), which upheld bans on certain semi-automatic rifles, Jackson v. San Francisco (2014), which upheld trigger lock ordnances similar to those struck down in Heller, Peruta v. San Diego County (2016), which upheld restrictive concealed carry licensing in California, and Silvester v. Becerra (2017), which upheld waiting periods for firearm purchasers who have already passed background checks and already own firearms. He was joined by Justice Scalia in the former two, and by Justice Gorsuch in Peruta.

In January 2011, the liberal advocacy group Common Cause reported that between 2003 and 2007 Thomas failed to disclose $686,589 in income earned by his wife from the Heritage Foundation, instead reporting "none" where "spousal noninvestment income" would be reported on his Supreme Court financial disclosure forms. The following week, Thomas stated that the disclosure of his wife's income had been "inadvertently omitted due to a misunderstanding of the filing instructions". Thomas amended reports going back to 1989.

In Hudson v. McMillian, a prisoner had been beaten, garnering a cracked lip, broken dental plate, loosened teeth, cuts, and bruises. Although these were not "serious injuries", the court believed, it held that "the use of excessive physical force against a prisoner may constitute cruel and unusual punishment even though the inmate does not suffer serious injury." Dissenting, Thomas wrote that, in his view, "a use of force that causes only insignificant harm to a prisoner may be immoral, it may be tortious, it may be Criminal, and it may even be remediable under other provisions of the Federal Constitution, but it is not 'cruel and unusual punishment'. In concluding to the contrary, the Court today goes far beyond our precedents." Thomas's vote—in one of his first cases after joining the court—was an early Example of his willingness to be the sole dissenter (Scalia later joined the opinion). Thomas's opinion was criticized by the seven-member majority of the court, which wrote that, by comparing physical assault to other prison conditions such as poor prison food, Thomas's opinion ignored "the concepts of dignity, civilized standards, humanity, and decency that animate the Eighth Amendment". According to Historian David Garrow, Thomas's dissent in Hudson was a "classic call for federal judicial restraint, reminiscent of views that were held by Felix Frankfurter and John M. Harlan II a generation earlier, but editorial criticism rained down on him". Thomas would later respond to the accusation "that I supported the beating of prisoners in that case. Well, one must either be illiterate or fraught with malice to reach that conclusion… no honest reading can reach such a conclusion."

Clarence Thomas wrote an autobiography addressing Anita Hill's allegations, and she also wrote an autobiography addressing her experience in the hearings. On February 19, 2018, Abramson followed up her 1995 book on Thomas and the Anita Hill hearings with a discussion concerning new evidence that Thomas had committed perjury which might be tied to possible impeachment. Abramson indicated that her reporting was initiated by an article by the Journalist Marcia Coyle from 2016 when Abramson stated, "Tipped to the post by a Maryland legal source who knew Smith (who made the allegations), Marcia Coyle, a highly regarded and scrupulously nonideological Supreme Court reporter for The National Law Journal, wrote a detailed story about (Moira) Smith’s allegation of butt-squeezing, which included corroboration from Smith’s roommates at the time of the dinner and from her former husband. Coyle’s story, which Thomas denied, was published October 27, 2016".

U.S. Presidents of that era submitted lists of potential federal court nominees to the American Bar Association (ABA) for a confidential rating of their judicial temperament, competence and integrity on a three-level scale of well qualified, qualified or unqualified. However, as noted by Adam Liptak of the New York Times, the ABA has historically taken generally liberal positions on divisive issues, and studies suggest that candidates nominated by Democratic Presidents fare better in the group’s ratings than those nominated by Republicans. Anticipating that the ABA would rate Thomas more poorly than they thought he deserved, the White House and Republican Senators pressured the ABA for at least the mid-level qualified rating, and simultaneously attempted to discredit the ABA as partisan. The ABA did rate Thomas as qualified, although with one of the lowest levels of support for a Supreme Court nominee. Ultimately, the ABA rating ended up having little impact on Thomas' nomination.