Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Pharaoh |

| Birth Place | Alexandria, Greek |

| Died On | 10 or 12 August 30 BC (aged 39)\nAlexandria, Egypt |

| Reign | 51 – 10 or 12 August 30 BC (21 years) |

| Predecessor | Ptolemy XII Auletes |

| Successor | Ptolemy XV Caesarion |

| Co-rulers | Ptolemy XII Auletes Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator Ptolemy XIV Ptolemy XV Caesarion |

| Burial | Unknown (probably in Egypt) |

| Spouse | Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator Ptolemy XIV Mark Antony |

| Issue | Caesarion, Ptolemy XV Philopator Philometor Caesar Alexander Helios Cleopatra Selene, Queen of Mauretania Ptolemy XVI Philadelphus |

| Full name | Full name Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator |

| Dynasty | Ptolemaic |

| Father | Ptolemy XII Auletes |

| Mother | Unknown, presumably Cleopatra VI Tryphaena (also known as Cleopatra V Tryphaena) |

Net worth: $18 Million (2024)

Cleopatra, famously known as the Pharaoh of Egypt in Greek, was undoubtedly a woman of immense wealth. In 2024, her net worth is estimated to be an astonishing $18 million, making her one of the richest individuals of her time. As the last active ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, Cleopatra's access to the kingdom's resources and trade routes allowed her to amass a significant fortune. Her opulent lifestyle, adorned with luxurious possessions, lavish palaces, and an entourage of loyal servants, further solidifies her reputation as one of history's wealthiest and most influential figures.

Biography/Timeline

In modern times Cleopatra has become an icon of popular culture, a reputation shaped by theatrical dramas dating back to the Renaissance as well as visual arts, such as paintings and films. This material largely surpasses the scope and size of existent historiographic literature about her from Classical Antiquity and has made a greater impact on the general public's view of Cleopatra than the latter. The 14th-century English poet Chaucer, in The Legend of Good Women, contextualized Cleopatra for the Christian world of the Middle Ages. His depiction of Cleopatra and Antony, her shining knight engaged in courtly love, has been interpreted in modern times as being either playful or misogynyistic satire. However, Chaucer highlighted Cleopatra's relationships with only two men as hardly the life of a seductress and wrote his works partly in reaction to the negative depiction of Cleopatra in De Mulieribus Claris and De Casibus Virorum Illustrium by the 14th-century Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio. The Renaissance humanist Bernardino Cacciante, in his 1504 Libretto apologetico delle donne, was the first Italian to defend the reputation of Cleopatra and criticize the perceived moralizing and misogyny in Boccaccio's works. Works of Arabic, Islamic historiography covered the reign of Cleopatra, such as the 10th-century AD Meadows of Gold by Al-Masudi, although his work erroneously claimed that Octavian died soon after Cleopatra's suicide.

Cleopatra's legacy survives in numerous works of art, both ancient and modern, and many dramatizations of incidents from her life in literature and other media. She was described in various works of Roman historiography and featured heavily in ancient Latin poetry. The latter produced a generally polemic and negative view of the queen that pervaded later Medieval and Renaissance literature. In the visual arts, ancient depictions of Cleopatra include Roman and Ptolemaic coinage, statues, busts, reliefs, cameo glass, cameo carvings, and paintings. She was the subject of many works in Renaissance and Baroque art, which included sculptures, paintings, poetry, theatrical dramas such as william Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra (1608) and operas such as George Frideric Handel's Giulio Cesare in Egitto (1724). In modern times Cleopatra has appeared in both the applied and fine arts, burlesque satire, Hollywood films such as Cleopatra (1963), and brand images for commercial products, becoming a pop culture icon of Egyptomania since the Victorian era.

In 1818 a now lost encaustic painting was discovered in the Temple of Serapis at Hadrian's Villa near Tivoli, Lazio, Italy that depicted Cleopatra committing suicide with an asp biting her bare chest. A chemical analysis performed in 1822 confirmed that the medium for the painting was composed of one-third wax and two-thirds resin. The thickness of the painting over Cleopatra's bare flesh and her drapery were reportedly similar to the paintings of the Fayum mummy portraits. A steel engraving published by John Sartain in 1885 depicting the painting as described in the archaeological report shows Cleopatra wearing authentic clothing and jewelry of Egypt in the late Hellenistic period, as well as the radiant crown of the Ptolemaic rulers, as seen in their portraits on various coins minted during their respective reigns. After Cleopatra's suicide, Octavian commissioned a painting to be made depicting her being bitten by a snake, parading this image in her stead during his triumphal procession in Rome. The portrait painting of Cleopatra's death was ostensibly taken from Rome along with the bulk of artworks and treasures used by Emperor Hadrian to decorate his private villa, including the temple where the painting was found.

Other possible but disputed busts of Cleopatra include one in the British Museum, London, made of limestone, which perhaps only depicts a woman in her entourage during her trip to Rome. The woman in this bust has facial features similar to other portraits (including the pronounced aquiline nose), but lacks a royal diadem and Sports a different hairstyle. However, the British Museum bust could potentially represent Cleopatra at a different stage in her life and may also betray an effort by Cleopatra to discard the use of royal insignia (i.e. the diadem) to make herself more appealing to the citizens of Republican Rome. Duane W. Roller speculates that the British Museum bust, along with those in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, the Capitoline Museums, Rome, and in the private collection of Maurice Nahmen (1868–1948), while having similar facial features and hairstyles as the Berlin bust but lacking a royal diadem, most likely represent members of the royal court or even Roman women imitating Cleopatra's popular hairstyle.

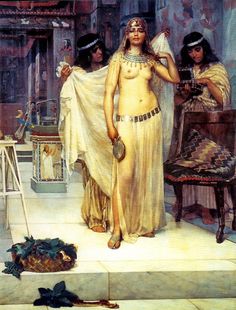

In Victorian Britain, Cleopatra was highly associated with many aspects of ancient Egyptian culture and her image was used to market various household products, including oil lamps, lithographs, postcards and cigarettes. Fictional novels such as H. Rider Haggard's Cleopatra (1889) and Théophile Gautier's One of Cleopatra's Nights (1838) depicted the queen as a sensual and mystic Easterner, while the Egyptologist Georg Ebers' Cleopatra (1894) was more grounded in historical accuracy. The French dramatist Victorien Sardou and Irish Playwright George Bernard Shaw produced plays about Cleopatra, while burlesque shows such as F. C. Burnand's Antony and Cleopatra offered satirical depictions of the queen connecting her and the environment she lived in with the modern age. Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra was considered canonical by the Victorian era. Its popularity led to the perception that the 1885 painting by Lawrence Alma-Tadema depicted the meeting of Antony and Cleopatra on her pleasure barge in Tarsus, although Alma-Tadema revealed in a private letter that it depicts a subsequent meeting of theirs in Alexandria. In his (unfinished) 1825 short story Egyptian Nights, Alexander Pushkin popularized the largely-ignored claims of 4th-century Roman Historian Sextus Aurelius Victor that Cleopatra prostituted herself to men who paid for sex with their lives. Cleopatra also became appreciated outside the Western world and Middle East, as the Qing-dynasty Chinese scholar Yan Fu (1854–1921) wrote an extensive biography about her.

Georges Méliès' Robbing Cleopatra's Tomb (French: Cléopâtre), an 1899 French silent horror film, was the first film to depict the character of Cleopatra. Hollywood films of the 20th century were influenced by earlier Victorian media, which helped to shape the character of Cleopatra played by Theda Bara in Cleopatra (1917), Claudette Colbert in Cleopatra (1934), and Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra (1963). In addition to her portrayal as a 'vampire' queen, Bara's Cleopatra also incorporated elements of 19th-century Orientalism, such as despotism, mixed with dangerous, overt female sexuality. Colbert's character of Cleopatra served as a glamour model for selling Egytpian-themed products in department stores in the 1930s, which can be linked to Director Cecil B. DeMille's filming techniques and emphasis on consumer commodities targeting female moviegoers. In preparation for the film starring Taylor as Cleopatra, women's magazines of the early 1960s advertised how to use makeup, clothes, jewelry, and hairstyles to achieve the 'Egyptian' look similar to the queens Cleopatra and Nefertiti. By the end of the 20th century there were not only forty-three separate films associated with Cleopatra, but also some two hundred plays and novels, forty-five operas, and five ballets.

Cleopatra's gender has perhaps led to her depiction as a minor if not insignificant figure in ancient, medieval, and even modern historiography about ancient Egypt and the Greco-Roman world. For instance, the Historian Ronald Syme (1903–1989) asserted that she was of little importance to Julius Caesar and that the propaganda of Octavian magnified her importance to an excessive degree. Although the Common view of Cleopatra was one of a prolific seductress, she had only two known sexual partners, Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, the two most prominent Romans of the time period who were most likely to ensure the survival of her dynasty. Ancient sources also describe Cleopatra as having had a stronger personality and charming wit than physical beauty.

In the House of Marcus Fabius Rufus at Pompeii, Italy a mid-1st century BC Second-Style wall painting of the goddess Venus holding a cupid near massive temple doors is most likely a depiction of Cleopatra VII as Venus Genetrix with her son Caesarion. The commission of the painting most likely coincides with the erection of the Temple of Venus Genetrix in the Forum of Caesar in September 46 BC, where Julius Caesar had a gilded statue erected depicting Cleopatra. This statue likely formed the basis of her depictions in both sculpted art as well as this painting at Pompeii. The woman in the painting wears a royal diadem over her head and is strikingly similar in appearance to the Vatican Cleopatra bust, which bears possible marks on the marble of its left cheek where a cupid's arm may have been torn off. The room with the painting was walled off by its owner, perhaps in reaction to the execution of Caesarion in 30 BC by order of Octavian, when public depictions of Cleopatra's son would have been unfavorable with the new Roman regime. Behind her golden diadem crowned with a red jewel is a translucent veil with crinkles that suggest the 'melon' hairstyle favored by the queen. Her skin is ivory white, her face round, her nose long and aquiline, and her large round eyes are deep-set, features that were Common in both Roman and Ptolemaic-Egyptian depictions of deities. Roller affirms that "there seems little doubt that this is a depiction of Cleopatra and Caesarion before the doors of the Temple of Venus in the Forum Julium and, as such, it becomes the only extant contemporary painting of the queen."

In a 1949 publication, Frances Pratt and Becca Fizel rejected the idea proposed by some scholars in the 19th and early 20th centuries that the painting was perhaps done by an Artist of the Italian Renaissance. Pratt and Fizel highlighted the Classical-style of the painting as preserved in textual descriptions and the steel engraving. They argued that it was unlikely for a Renaissance-period Painter to have painted works with encaustic materials, conducted thorough research into Hellenistic-period Egyptian clothing and jewelry as depicted in the painting, and then precariously placed it in the ruins of the Egyptian temple at Hadrian's Villa.

Since the 1950s scholars have debated whether or not the Esquiline Venus—discovered in 1874 on the Esquiline Hill in Rome and housed in the Palazzo dei Conservatori of the Capitoline Museums—is a depiction of Cleopatra, based on the statue's hairstyle and facial features, apparent royal diadem worn over the head, and the uraeus Egyptian cobra wrapped around the base. Detractors of this theory argue that the facial features on the Berlin bust and coinage of Cleopatra differ and assert that it was unlikely she would be depicted as the naked goddess Venus (i.e. the Greek Aphrodite). However, she was depicted in an Egyptian statue as the goddess Isis. The Esquiline Venus is generally thought to be a mid-1st-century AD Roman copy of a 1st-century BC Greek original from the school of Pasiteles.

Cleopatra was depicted in various ancient works of art, in the Egyptian as well as Hellenistic-Greek and Roman styles. Surviving works include statues, busts, reliefs, and minted coins, as well as an ancient carved cameos, such as one depicting Cleopatra and Mark Antony in Hellenistic style, now in the Altes Museum, Berlin. Contemporary images of Cleopatra were produced both in and outside of Ptolemaic Egypt. For instance, a large gilded bronze statue of Cleopatra once existed inside the Temple of Venus Genetrix in Rome, the first time that a living person had their statue placed next to that of a deity in a Roman temple. It was erected there by Julius Caesar and remained in the temple at least until the 3rd century AD, its preservation perhaps owing to Caesar's patronage, although Augustus did not remove or destroy artworks in Alexandria depicting Cleopatra. In regards to surviving Roman statuary, a life-sized Roman-style statue of Cleopatra was found near the Tomba di Nerone, Rome along the Via Cassia and is now housed in the Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums. Plutarch, in his Life of Antonius, claimed that the public statues of Mark Antony were torn down by Augustus, but those of Cleopatra were preserved following her death thanks to her friend Archibius paying the Emperor 2,000 talents to dissuade him from destroying hers.

The Bust of Cleopatra in the Royal Ontario Museum represents a bust of Cleopatra in the Egyptian style. Dated to the mid-1st-century BC, it is perhaps the earliest depiction of Cleopatra as both a goddess and ruling pharaoh of Egypt. This sculpture also has pronounced eyes that share similarities with Roman copies of Ptolemaic sculpted works of art. The Dendera Temple complex near Dendera, Egypt, contains Egyptian-style carved relief images along the exterior walls of the Temple of Hathor depicting Cleopatra and her young son Caesarion as a fully-grown adult and ruling pharaoh making offerings to the gods. Augustus had his name inscribed there following the death of Cleopatra. A large Ptolemaic black basalt statue measuring 41 in (1.04 m) in height, located now at the Hermitage Museum of Saint Petersburg, Russia, is thought to represent Arsinoe II, wife of Ptolemy II, but recent analysis has indicated that it could depict her descendant Cleopatra VII due to the three uraei adorning her headdress, an increase from the two used by Arsinoe II to symbolize her rule over Lower and Upper Egypt. The woman in the basalt statue also holds a divided, double cornucopia (dikeras), which can be seen on coins of both Arsinoe II and Cleopatra VII. In his Kleopatra und die Caesaren (2006), Bernard Andreae contends that this basalt statue, like other idealized Egyptian portraits of the queen, does not contain realistic facial features and hence adds little to the knowledge of her appearance.

Another painting from Pompeii, dated to the early 1st century AD and located in the House of Giuseppe II, contains a possible depiction of Cleopatra VII with her son Caesarion, both wearing royal diadems while she reclines and consumes poison in an act of suicide. The painting was originally thought to depict the Carthaginian noblewoman Sophonisba, who towards the end of the Second Punic War (218–201 BC) drank poison and committed suicide at the behest of her lover Masinissa, King of Numidia. Arguments in favor of it depicting Cleopatra include the strong connection of her house with that of the Numidian royal family, Masinissa and Ptolemy VIII having been associates and Cleopatra's own daughter marrying the Numidian Prince Juba II. Sophonisba was also a more obscure figure when this painting was made, while Cleopatra's suicide was far more famous. An asp is absent from the painting, but many Romans held the view that she received poison in another manner than a venomous snakebite. A set of double doors on the rear wall of the painting, positioned very high above the people in it, suggests the described layout of Cleopatra's tomb in Alexandria. A male servant holds the mouth of an artificial Egyptian crocodile (possibly an elaborate tray handle), while another man standing by is dressed as a Roman.

When Ptolemy XIII realized that his sister was in the palace and consorting directly with Caesar, he attempted to rouse the populace of Alexandria into a riot, but he was arrested by Caesar who used his oratorical skills to calm the frenzied crowd. Caesar then brought Cleopatra VII and Ptolemy XIII before the assembly of Alexandria, where Caesar revealed the written will of Ptolemy XII—previously possessed by Pompey—naming Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII as his joint heirs. Caesar then attempted to arrange for the other two siblings, Arsinoe IV and Ptolemy XIV, to rule together over Cyprus, thus removing potential rival claimants to the Egyptian throne while also appeasing the Ptolemaic subjects still bitter over the loss of Cyprus to the Romans in 58 BC.