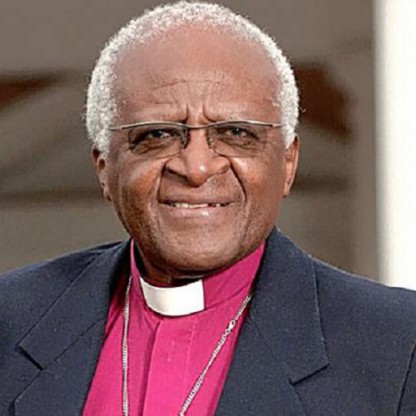

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Anti-Apartheid Activist |

| Birth Day | October 07, 1931 |

| Birth Place | Klerksdorp, South African |

| Age | 91 YEARS OLD |

| Birth Sign | Scorpio |

| Church | Anglican Church of Southern Africa |

| See | Cape Town (retired) |

| Installed | 7 September 1986 |

| Term ended | 1996 |

| Predecessor | Philip Russell |

| Successor | Njongonkulu Ndungane |

| Other posts | Bishop of Lesotho Bishop of Johannesburg Archbishop of Cape Town |

| Ordination | Deacon 1960 Priest 1961 |

| Consecration | 1976 |

| Birth name | Desmond Mpilo Tutu |

| Spouse | Nomalizo Leah Shenxane (m. 1955) |

| Education | King's College London |

| Alma mater | King's College London |

| Reference style | Archbishop |

| Spoken style | Your Grace |

| Religious style | The Most Reverend |

Net worth: $48 Million (2024)

Desmond Tutu, the renowned anti-apartheid activist in South Africa, is estimated to have a net worth of $48 million in 2024. Tutu has long been an influential figure in the fight against racial segregation and injustice, playing a significant role in altering the course of history in his country. As a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, his efforts to dismantle the apartheid system have garnered international recognition. While his net worth speaks to his successful career and global impact, Tutu's true wealth lies in the lasting impact he has made on human rights and social justice.

Biography/Timeline

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born on 7 October 1931 in Klerksdorp, a city in North West South Africa. His mother, Allen Dorothea Mavoertsek Mathlare, was born to a Motswana family in Boksburg. His father, Zachariah Zelilo Tutu, was from the anaMfengu branch of Xhosa and had grown up in Gcuwa, Eastern Cape. At home, the couple both spoke Xhosa. Zachariah trained as a primary school Teacher at Lovedale college before taking a post in Boksburg, where he married his wife. In the late 1920s, he took a job in Klerksdorp; in the Afrikaaner-founded city, he and his wife resided in the black residential area. Established in 1907, it was then known as the "native location" although was later renamed Makoetend. The native location housed a diverse community; although most were Tswana, it also housed Xhosa, Sotho, and a few Indian traders. Zachariah worked as the principal of a Methodist primary school and the family lived in the schoolmaster's house, a small mud-brick building in the yard of the Methodist mission.

The Tutus were poor; describing his family, Tutu later related that "although we weren't affluent, we were not destitute either". Tutu had an older sister Sylvia, who called him "Mpilo" ("life"), a name given to him by his paternal grandmother. The rest of the family called him "Boy". He was his parent's second son; their firstborn boy, Sipho, had died in infancy. Tutu was sickly from birth; polio resulted in the atrophy of his right hand, and another time he was hospitalised with serious burns. Tutu had a close relationship and was fond of his father, although was angered at the latter's heavy drinking, during which he would sometimes beat his wife. The family were initially Methodists and Tutu was baptised into the Methodist Church in June 1932. They subsequently changed denominations, first to the African Methodist Episcopal Church and then to the Anglican Church.

In 1936, the family moved to Tshing, where Zachariah was employed as the principle of a Methodist school; they lived in a hut in the school yard. There, Tutu started his primary education and played football with the other children, also becoming the server at St Francis Anglican Church. He developed a love of reading, particularly enjoying comic books and European fairy tales. Here, he also learned Afrikaans, the main language of the area. It was in Tshing that his parents had a third son, Tamsanqa, who also died in infancy. Around 1941, Tutu's mother moved to Witwatersrand to work as a cook at Ezenzeleni, an institute for the blind in western Johannesburg. Tutu joined her in the city, first living with an aunt in Roodepoort West before they secured their own house in the township. In Johannesburg, he attended a Methodist primary school before transferring to the Swedish Boarding School (SBS) in the St Agnes Mission. Several months later, he moved with his father to Ermelo, eastern Transvaal. After six months, the duo returned to live with the rest of the family in Roodepoort West, where Tutu resuming his studies at SBS. He had pursued his interest in Christianity and at the age of 12 underwent confirmation at St Mary's Church, Roodepoort.

Tutu failed the arithmetic component of his primary school exam, but despite this, his father secured him entry to the Johannesburg Bantu High School in 1945, where he excelled academically. There, he joined a school rugby team, developing a lifelong love of the sport. Outside of school, he earned money selling oranges and as a caddy for white golfers. To avoid the expense of a daily train commute to school, he briefly lived with family nearer to Johannesburg, before moving back in with his parents when they relocated to Munsieville. He returned to Johannesburg by moving into a hostel that was part of the Anglican complex surrounding the Church of Christ the King in Sophiatown. He became a server at the church and came under the influence of its priest, Trevor Huddleston. In 1947, Tutu contracted tuberculosis and was hospitalised in Rietfontein for 18 months, during which he spent much of his time reading. In the hospital, he underwent a circumcision to mark his transition to manhood. He returned to school in 1949 and took his national exams in late 1950, gaining a second-class pass.

Wanting to become a Doctor, Tutu secured admission to study Medicine at the University of the Witwatersrand; however, his parents could not afford the tuition fees. Instead, he turned toward teaching, gaining a government scholarship to start a course at Pretoria Bantu Normal College, a Teacher training institution, in 1951. There, he served as treasurer of the Student Representative Councillor, helping to organise the Literacy and Dramatic Society, and chairing the Cultural and Debating Society for two years. It was during one local debating event that he first met the Lawyer and Future President Nelson Mandela; the latter did not remember the meeting and they would not encounter each other again until 1990. At the college, he attained his Transvaal Bantu Teachers Diploma, having gained advice about taking exams from the Activist Robert Sobukwe. He had also taken five correspondence courses provided by the University of South Africa (UNISA), graduating in the same class as Future Zimbabwean leader Robert Mugabe.

In 1953, the far-right National Party government had introduced the Bantu Education Act as a means of furthering their apartheid cause; both Tutu and his wife disliked these reforms and decided to leave the teaching profession. With Huddleston's support, Tutu left the teaching profession to become an Anglican priest. In January 1956, his request to join the Ordinands Guild was turned down due to the debts he had accrued; these were then paid off by the wealthy industrialist and philanthropist Harry Oppenheimer. Tutu was admitted to St Peter's Theological College in Rosettenville, Johannesburg, which was run by the Anglican Community of the Resurrection. The college was residential, and Tutu lived there while his wife moved to train as a nurse in Sekhukhuneland and his children lived with his parents in Munsieville. In August 1960, his wife gave birth to another daughter, Naomi.

In 1954 he began teaching English at Madibane High School; the following year, he transferred to the Krugersdorp High School, where he taught English and history. He began courting Nomalizo Leah Shenxane, a friend of his sister Gloria who was studying to become a primary school Teacher. They were legally married at Krugersdorp Native Commissioner's Court in June 1955, before undergoing a Roman Catholic wedding ceremony at the Church of Mary Queen of Apostles; although he was a Protestant, Tutu had agreed to the ceremony due to Leah's Roman Catholic faith. The newly married couple initially lived in a room at Tutu's parental home before renting their own home six months later. Their first child, Trevor, was born in April 1956; their first daughter, Thandeka, appeared 16 months later. The couple worshipped at St Paul's Church, where Tutu volunteered as a Sunday school Teacher, assistant choirmaster, church councillor, lay preacher, and sub-deacon, while outside of the church he also volunteered as a football administrator for a local team.

In December 1960, Edward Paget ordained Tutu as an Anglican minister at St Mary's Cathedral. Tutu was then appointed assistant curate in St Alban's Parish, Benoni, where he was reunited with his wife and children; they lived in a converted garage. He earned 72.50 rand a month, which was two-thirds of what his white counterparts were given. In 1962, Tutu was transferred to St Philip's Church in Thokoza, where he was placed in charge of the congregation and developed a passion for pastoral ministry. Many in South Africa's white-dominated Anglican establishment felt the need for a greater number of indigenous Africans in positions of ecclesiastical authority; to assist in this, Aelfred Stubbs proposed that Tutu be trained as a theology Teacher at King's College London (KCL) in Britain. Funding was secured from the International Missionary Council's Theological Education Fund (TEF), and the government agreed to give the Tutus permission to move to Britain.

At KCL's theology department, Tutu studied under Theologians like Dennis Nineham, Christopher Evans, Sydney Evans, Geoffrey Parrinden, and Eric Mascall. In London, the Tutus felt liberated experiencing a life free from apartheid and the pass laws of South Africa; he later noted that "there is racism in England, but we were not exposed to it". The family moved into the curate's flat behind the Church of St Alban the Martyr in Golders Green; they were allowed to live rent-free on the condition that Tutu assisted Sunday services, the first time that he had ministered to a white congregation. It was in the flat that a daughter, Mpho Andrea, was born in 1963. Tutu was academically successful and his tutors suggested that he convert to a honours degree, which entailed him also studying Hebrew.

Nearing the end of his bachelor of arts studies, he decided to continue on to a master's degree, securing a TEF grant to fund it; he studied for this degree from October 1965 until September 1966, completing his dissertation on Islam in West Africa. During this period, the family moved from Golders Green to Bletchingley in Surrey, where Tutu worked as the assistant curate of St Mary's Church. In the village, he encouraged cooperation between his Anglican parishioners and the local Roman Catholic and Methodist communities. Tutu's time in London helped him to jettison any bitterness to whites and feelings of racial inferiority; he overcame his habit of automatically deferring to whites.

In 1966, the Tutus left the UK and travelled, via Paris and Rome, to East Jerusalem. Spending two months in the city, Tutu studied Arabic and Greek at St George's College. He was shocked at the level of tension between the city's Jewish and Arab citizens. From there, the family returned to South Africa, spending Christmas with family in Witwatersrand. They found it difficult readjusting to a society where they were impacted by segregation and pass laws. He explored the possibility on conducting a PhD at UNISA, on the subject of Moses in the Quran, but this project never materialised. In 1967 they proceeded to Alice, Eastern Cape, where the Federal Theological Seminary (Fedsem) had recently been established, an amalgamation of training institutions from different Christian denominations. There, Tutu was employed teaching doctrine, the Old Testament, and Greek. Tutu was the college's first black staff-member, with most of the others being European or American expatriates. The campus allowed a level of racial-mixing which was absent in most of South African society. Leah also gained employment there, as a library assistant. They sent their children to a private boarding school in Swaziland, thereby ensuring that they were not instructed under the government's Bantu Education syllabus.

Tutu used his position to speak out about what he regarded as social injustice. He met with Black Consciousness Movement figures like Mamphela Ramphele and Soweto community Leaders like Nthano Motlana, and publicly endorsed international economic boycott of South Africa over its apartheid policy. He opposed the government's Terrorism Act, 1967 and shared a platform with anti-apartheid campaigner Winnie Mandela in condemning it. He held a 24-hour vigil for racial harmony at the cathedral where he included special prayers for those Activists detained under the act. In May 1976, he wrote a letter to Prime Minister B. J. Vorster, urging him to dismantle apartheid and warning that if the government continued enforcing this policy then the country would erupt in racial violence. Six weeks later, the Soweto Uprising broke out as black youth protesting the introduction of Afrikaans as the mandatory language of instruction clashed with police. Over the course of ten months, at least 660 were killed, the majority of them under the age of 24. Tutu was upset by what he regarded as the lack of outrage from South Africa's white community; he raised the issue in his Sunday sermon, stating that the white silence was "deafening" and asking if they would have shown the same nonchalance had the school children killed by police and pro-government paramilitaries been white.

While at St Peter's, Tutu had also joined a pan-Protestant group, the Church Unity Commission, and served as a delegate at Anglican-Catholic conversations in southern Africa. It was also at this point that he began publishing in academic journals and journals of current affairs. Tutu was also appointed as the Anglican chaplain to the neighbouring University of Fort Hare. In an unusual move for the time, he invited female students to become servers during the Eucharist alongside their male counterparts. He joined Anglican student delegations to meetings of the Anglican Students' Federation and the University Christian Movement. It was from this environment that the Black Consciousness Movement emerged under the leadership of figures like Steve Biko and Barney Pityana; although not averse to working with other racial groups to fight apartheid, Tutu was supportive of their efforts. In August 1968, he gave a sermon comparing the situation in South Africa with that in the Eastern Bloc, likening anti-apartheid protests to the recent Prague Spring. In September, Fort Hare students held a sit-in protest at the university administration's policies; after they were surrounded by police with dogs, Tutu waded into the crowd to pray with the protesters. This was the first time that he had witnessed state power used to suppress dissent, and he cried during public prayers the next day.

During Tutu's rise to notability during the 1970s and 1980s, responses to him were "sharply polarized". He gained much adulation from black journalists, inspired imprisoned anti-apartheid Activists, and led to many black parents naming their children after him. By 1984 he was—according to Gish—"the personification of the South African freedom struggle". Conversely, the response he received from South Africa's white minority was more mixed. Most of those who criticised him were conservative whites who did not want a shift away from apartheid and white-minority rule. Many of these whites were angered that he was calling for economic sanctions against South Africa and that he was warning that racial violence was impending. This hostility was exacerbated by the government's campaign to discredit Tutu and distort his image. Allen noted that in 1984, Tutu was "the black leader white South Africans most loved to hate" and that this antipathy extended beyond supporters of the far-right government to liberals too.

The TEF offered Tutu a job as their Director for Africa, a position that would require relocating to London. Tutu agreed, although was initially refused permission to leave by the South African authorities; they regarded him with suspicion ever since his involvement in the Fort Hare student protests and were also increasingly antagonistic toward the WCC, which ran the TEF, bceause it had condemned apartheid as un-Christian. After Tutu insisted that taking the position would be good publicity for South Africa, the authorities relented. In March 1972, he returned to Britain. The TEF's headquarters were in Bromley, a town in the southeast of the city, with the Tutu family settling in nearby Grove Park, where Tutu became honorary curate of St Augustine's Church.

In 1975 he moved into what is now known as Tutu House on Soweto's well known Vilakazi Street, which is also the location of a house in which the late Nelson Mandela once lived. It is said to be one of the few streets in the world where two Nobel Prize winners have lived.

Tutu had been scheduled to serve a seven-year term as dean, however after seven months he was nominated as a candidate in an election for the position of Bishop of Lesotho. Although Tutu stipulated that he did not want the position, he was elected to the position regardless in March 1976, at which he reluctantly accepted it. This decision upset some of his congregation, who felt that he had used their parish as a stepping stone for his personal career advancement. In July, Bill Burnett consecrated Tutu as a bishop at St Mary's Cathedral. In August, Tutu was enthroned as the Bishop of Lesotho in a ceremony at Maseru's Cathedral of St Mary and St James; thousands attended, including King Moshoeshoe II and Prime Minister Leabua Jonathan. In this position, he travelled around the diocese, often visiting parishes in the mountains. He learned the Sesotho language and developed a deep affection for the country. He appointed Philip Mokuku as the first dean of the diocese and placed great emphasis on further education for the Basotho clergy. He befriended the royal family although his relationship with Jonathan's right-wing government, of which he disapproved, was strained. In September 1977 he returned to South Africa after being invited to speak at the Eastern Cape funeral of Black Consciousness Activist Steve Biko, who had been killed by police while in their custody. At the funeral, Tutu stated that Black Consciousness was "a movement by which God, through Steve, sought to awaken in the black person a sense of his intrinsic value and worth as a child of God".

Tutu was the SACC's first black leader, and at the time, the SACC was one of the only Christian institutions in South Africa where black people had the majority representation. There, he introduced a schedule of daily staff prayers, regular Bible study, monthly Eucharist, and silent retreats. He also developed a new style of leadership, appointing senior staff who were capable of taking the initiative, delegating much of the SACC's detailed work to them, and keeping in touch with them through meetings and memorandums. Many of his staff referred to him as "Baba" (father). He was determined that the SACC become one of South Africa's most visible human rights advocacy organisations, a course which would anger the government. His efforts gained him international recognition; in 1978 Kings College London elected him a fellow while the University of Kent and General Theological Seminary gave him honorary doctorates; the following year Harvard University also gave him an honorary doctorate.

After Tutu told Danish journalists that he supported an international economic boycott of South Africa, he was called before two government ministers to be reprimanded in October 1979. In March 1980, the government confiscated his passport, an act which raised his international profile and brought condemnations from the US State Department and senior Anglicans like Robert Runcie. Tutu also signed a petition calling for the released of Mandela, an imprisoned anti-apartheid activist; Mandela's freedom was not yet an international cause célèbre. This led to a correspondence between the two men. In 1980, the SACC committed itself to supporting civil disobedience against South Africa's racial laws. After Thorne was arrested in May, Tutu and Joe Wing led a march of protest, during which they were arrested by riot police, imprisoned overnight, and fined. The authorities confiscated Tutu's passport. In the aftermath of the incident, a meeting was organised between 20 church Leaders, including Tutu, and Botha and seven government ministers. At this August meeting the clerical Leaders unsuccessfully urged the government to dismantle the apartheid laws. Some of the clergy saw this dialogue with the government as pointless, but Tutu disagreed, noting that "Moses went to Pharaoh repeatedly to secure the release of the Israelites".

He believed that it was the duty of Christians to oppose unjust laws. He felt that religious Leaders like himself should stay outside of party politics, citing the Example of Abel Muzorewa in Zimbabwe, Makarios III in Cyprus, and Ruhollah Khomeini in Iran as examples in which such crossovers proved problematic. He tried to avoid alignment with any particular political party; in the 1980s he for instance signed a plea urging anti-apartheid Activists in the United States to support both the ANC and the Pan Africanist Congress. When, in the late 1980s, there were suggestions that he should take political office, he rejected the idea.

In January 1981, the government returned Tutu's passport to him. In March, he embarked on a five-week visit to ten countries in Europe and North America, meeting politicians including the UN Secretary General Kurt Waldheim, and addressing the UN Special Committee Against Apartheid. In the UK, he met Runcie gave a sermon in Westminster Abbey, while in Rome he spent a few minutes with Pope John Paul II. On his return to South Africa, Botha again ordered his passport confiscated, preventing Tutu from personally collecting several further honorary degrees. It was returned to him 17 months later. In September 1982 he addressed the Triennial Convention of the Episcopal Church in New Orleans before traveling to Kentucky to see his daughter Naomi, who lived there with her American husband. He was troubled that President Ronald Reagan adopted a warmer relationship with the South African government than his predecessor Jimmy Carter, relating that Reagan's government was "an unmitigated disaster for us blacks". Tutu gained a popular following in the US, where he was often compared to civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., although white conservatives like Patrick Buchanan and Jerry Falwell lambasted him as an alleged communist sympathiser.

On 16 October 1984, the then Bishop Tutu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Nobel Committee cited his "role as a unifying leader figure in the campaign to resolve the Problem of apartheid in South Africa". This was seen as a gesture of support for him and The South African Council of Churches which he led at that time. In 1987 Tutu was awarded the Pacem in Terris Award. It was named after a 1963 encyclical letter by Pope John XXIII that calls upon all people of good will to secure peace among all nations.

In May 1985 he embarked on a speaking tour of the U.S., and in October 1985 addressed the political committee of the United Nations General Assembly urging that the international community impose sanctions on South Africa if apartheid was not dismantled within six months. He proceeded to the United Kingdom, where he met with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. He also announced the formation of a Bishop Tutu Scholarship Fund to financially assist South African students living in exile. He returned to the U.S. in May 1986, and in August 1986 visited Japan, China, and Jamaica to promote sanctions. Given that most senior anti-apartheid Activists were imprisoned, Mandela referred to Tutu as "public enemy number one for the powers that be".

Tutu has described himself as a socialist, in 1986 relating that "All my experiences with capitalism, I'm afraid, have indicated that it encourages some of the worst features in people. Eat or be eaten. It is underlined by the survival of the fittest. I can't buy that. I mean, maybe it's the awful face of capitalism, but I haven't seen the other face." Also in the 1980s, he was reported as saying that "apartheid has given free enterprise a bad name". Tutu has often used the aphorism that "African communism" is an oxymoron because—in his view—Africans are intrinsically spiritual and this conflicts with the atheistic nature of Marxism. He was critical of the Marxist governments in the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc, comparing the way that they treated their populations with the way that the National Party treated South Africans. In 1985 he stated that he hated communism "with every fiber of my being" although sought to explain why black South Africans turned to it as an ally: "when you are in a dungeon and a hand is stretched out to free you, you do not ask for the pedigree of the hand owner."

Alongside his domestic work, he also turned his attention to events elsewhere in Africa, and in 1987 gave the keynote speech at the All Africa Conference of Churches (AACC) in Lomé, Togo. There, he called on churches to champion the oppressed throughout the continent, stating that "it pains us to have to admit that there is less freedom and personal liberty in most of Africa now then there was during the much-maligned colonial days." At the conference, he was elected President of the AACC, while José Belo was elected its general-secretary. Calling for an "African renaissance" across the continent, the pair formed a partnership that would last a decade. In 1989 they visited Zaire to encourage the country's churches to distance themselves from Seko's autocratic government. In 1994, he and Belo visited war-torn Liberia in a mission co-organised by the AACC and the Carter Center. There, they met Charles Taylor, but Tutu did not trust his promise of a ceasefire. In 1995, Mandela sent Tutu to Nigeria to meet with Nigerian military leader Sani Abacha to request the release of imprisoned politicians Moshood Abiola and Olusegun Obasanjo. In July 1995, he visited Rwanda a year after the genocide, where he preached to 10,000 people in Kigali. Drawing on his experiences in South Africa, he called for justice to be tempered with mercy towards the Hutu who had orchestrated the genocide. Tutu also travelled to other parts of world, for instance spending March 1989 in Panama and Nicaragua.

Tutu also spoke out regarding The Troubles in Northern Ireland. At the Lambeth conference of 1988, he backed a resolution on the issue which condemned the use of violence by all sides; Tutu believed that, given Irish republicans had the right to vote, they had not exhausted peaceful means of bringing about change and thus should not resort to armed struggle. Three years later, he gave a televised Service from Dublin's Christ Church Cathedral where he called for negotiations to take place between all factions, including the Irish republican Sinn Féin and the Provisional Irish Republican Army, groups which Thatcher's UK government had refused to engage with. He visited Belfast in 1998 and again in 2001.

Tutu remained actively involved in acts of civil disobedience against the government; he was encouraged by the fact that many whites also took part in these protests. In August 1989 he helped to organise an "Ecumenical Defiance Service" at St George's Cathedral, and shortly after joined protests at segregated beaches outside Cape Town. To mark the sixth anniversary of the UDF's foundation he held a "service of witness" at the cathedral, and in September organised a church memorial for those protesters who had been killed in clashes with the security forces. He organised a protest march through Cape Town for later that month, which the new President F. W. de Klerk agreed to permit; a multi-racial crowd containing an estimated 30,000 people took part. That the march had been permitted inspired similar demonstrations to take place across the country. In October, de Klerk met with Tutu, Boesak, and Frank Chikane; Tutu was impressed that "we were listened to". In 1994, a further collection of Tutu's writings, The Rainbow People of God, was published, and followed the next year with his An African Prayer Book, a collection of prayers from across the continent accompanied by the Archbishop's commentary.

Like many other Activists, Tutu believed that there was a "third force" stoking the tensions between the ANC and Inkatha; it later emerged that sectors of the intelligence agencies were supplying Inkatha with weapons to weaken the ANC's negotiating position. Unlike some ANC figures, Tutu never accused de Klerk of personal complicity in these operations. In November 1990, Tutu organised a "summit" at Bishopscourt attended by both church Leaders and Leaders of political groups like the ANC, PAC, and AZAPO, in which he encouraged them to call on their supporters to avoid violence and allow free political campaigning. After the South African Communist Party leader Chris Hani was assassinated by a white man, Tutu served as preacher at Hani's funeral outside Soweto; despite his objections to Hani's Marxist beliefs, Tutu had admired him as an Activist. Amid these events, Tutu had experienced physical exhaustion and ill-health, and he undertook a four-month sabbatical at Emory University's Candler School of Theology in Atlanta, Georgia.

In 1991, Tutu's son Trevor was convicted of contravening the Civil Aviation Act for falsely claiming there was a bomb on board a South African Airways plane at East London Airport. He was granted bail pending appeal but failed to appear and was finally apprehended in Johannesburg in August 1997. He applied for and, in 1997, was granted amnesty from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of which Desmond was co-founder and chairman, attracting harsh criticism on suspicion of preferential treatment.

Tutu is generally credited with coining the term Rainbow Nation as a metaphor for post-apartheid South Africa after 1994 under African National Congress rule. The expression has since entered mainstream consciousness to describe South Africa's ethnic diversity. He had first used the metaphor in 1989 when he described a multi-racial protest crowd as the "rainbow people of God". Tutu advocated what liberation Theologians call "critical solidarity", offering support for pro-democracy forces while reserving the right to criticise his allies. He criticised Mandela on several points, such as his tendency to wear brightly coloured Madiba shirts, which he regarded as inappropriate; Mandela offered the tongue-in-cheek response that it was ironic coming from a man who wore dresses. More serious was Tutu's criticism of Mandela's retention of South Africa's apartheid-era armaments industry and the significant pay packet that newly elected Members of Parliament adopted. Mandela hit back, calling Tutu a "populist" and stating that he should have raised these issues privately rather than publicly.

A key question facing the post-apartheid government was how they would respond to the various human rights abuses that had been committed over the previous decades by both the state and by anti-apartheid Activists. The National Party had wanted a comprehensive amnesty package whereas the ANC wanted trials of former state figures. Alex Boraine helped Mandela's government to draw up legislation for the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which was passed by parliament in July 1995. Nuttall suggested that Tutu become one of the TRC's seventeen commissioners, while in September a synod of bishops formally nominated him. Tutu proposed that the TRC adopt a threefold approach: the first being confession, with those responsible for human rights abuses fully disclosing their activities, the second being forgiveness in the form of a legal amnesty from prosecution, and the third being restitution, with the perpetrators making amends to their victims.

The first hearing took place in April 1996. The hearings were publicly televised and had a considerable impact on South African society. He had very little control over the committee responsible for granting amnesty, instead chairing the committee which heard accounts of human rights abuses perpetrated by both anti-apartheid and apartheid figures. While listening to the testimony of victims, Tutu was sometimes overwhelmed by emotion and cried during the hearings. He singled out those victims who expressed forgiveness towards those who had harmed them and used these individuals as his leitmotif. The ANC's image was tarnished by the revelations that some of its Activists had engaged in torture, attacks on civilians, and other human rights abuses. It sought to suppress part of the final TRC report, infuriating Tutu. Tutu presented the five-volume TRC report to Mandela in a public ceremony in Pretoria in October 1998. Ultimately, Tutu was pleased with the TRC's achievement, believing that it would aid long-term reconciliation, although recognised its short-comings.

In 1997, Tutu was diagnosed with prostate cancer and underwent successful treatment in the US. He subsequently became patron of the South African Prostate Cancer Foundation, which was established in 2007.

After the apartheid era, Tutu's status as a gay rights Activist kept him in the public eye more than any other issue facing the Anglican Church. Tutu regarded discrimination against homosexuals as being the equivalent to discrimination against black people and women. He made his views on this issue known through speeches and sermons. After the 1998 Lambeth Conference of bishops reaffirmed the church's opposition to same-sex sexual acts, Tutu wrote to George Carey stating "I am ashamed to be an Anglican". He regarded the Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams as too accommodating of conservative Anglicans who wanted to eject various US and Canadian Anglican churches from the Anglican Communion after they expressed a pro-LGB rights stance. Tutu expressed the view that if these conservatives disliked the inclusiveness of the Anglican Communion, they always had "the freedom to leave". In 2007, Tutu accused the church of being obsessed with homosexuality and declared: "If God, as they say, is homophobic, I wouldn't worship that God." Tutu has said that in Future anti-gay laws will be regarded as just as wrong as apartheid laws. Tutu has also supported the inclusion of same-sex marriages within the Anglican Church of Southern Africa.

Freedom of the City awards have been conferred on Tutu in cities in Italy, Wales, England and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He has received numerous doctorates and fellowships at distinguished universities. He has been named a Grand Officer of the Légion d'honneur by France; Germany has awarded him the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, and he received the Sydney Peace Prize in 1999. He is also the recipient of the Gandhi Peace Prize, the King Hussein Prize and the Marion Doenhoff Prize for International Reconciliation and Understanding. In 2008, Governor Rod Blagojevich of Illinois proclaimed 13 May 'Desmond Tutu Day'. On his visit to Illinois, Tutu was awarded the Lincoln Leadership Prize and unveiled his portrait which will be displayed at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield. Queen Elizabeth II appointed him as a Bailiff Grand Cross of the Venerable Order of St. John in September 2017.

Tutu had retained his interest in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and after the signing of the Oslo Accords was invited to Tel Aviv to attend the Peres Centre for Peace. He became increasingly frustrated following the collapse of the 2000 Camp David Summit without an agreement. In 2002, he gave a widely publicised speech denouncing Israeli policy regarding the Palestinians and called for sanctions to be brought against Israel. Comparing the Israeli-Palestinian situation with that in South Africa, he said that "one reason we succeeded in South Africa that is missing in the Middle East is quality of leadership - Leaders willing to make unpopular compromises, to go against their own constituencies, because they have the wisdom to see that would ultimately make peace possible."

Tutu gained many international awards and honorary degrees, particularly in South Africa, the United Kingdom, and United States. By 2003, he had approximately 100 honorary degrees. Many schools and scholarships were named after him. For instance, in 2000 the Munsieville Library in Klerksdorp was renamed the Desmond Tutu Library. At Fort Hare University, the Desmond Tutu School of Theology was launched in 2002.

Naomi Tutu founded the Tutu Foundation for Development and Relief in Southern Africa, based in Hartford, Connecticut. She attended the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce at the University of Kentucky and has followed in her father's footsteps as a human rights Activist. She is currently a graduate student at Vanderbilt University Divinity School, in Nashville, Tennessee. Desmond Tutu's other daughter, Mpho Tutu, has also followed in her father's footsteps and in 2004 was ordained an Episcopal priest by her father. She is also the founder and executive Director of the Tutu Institute for Prayer and Pilgrimage and the chairperson of the board of the Global AIDS Alliance.

Before the 31st G8 summit at Gleneagles, Scotland, in 2005, Tutu called on world Leaders to promote free trade with poorer countries. Tutu also called on an end to expensive taxes on anti-AIDS drugs. Before the 32nd G8 summit in Heiligendamm, Germany, in 2007, Tutu called on the G8 to focus on poverty in the Third World. Following the United Nations Millennium Summit in 2000, it appeared that world Leaders were determined as never before to set and meet specific goals regarding extreme poverty.

Tutu was named to head a United Nations fact-finding mission to the Gaza Strip town of Beit Hanoun, where, in a November 2006 incident the Israel Defense Forces killed 19 civilians after troops wound up a week-long incursion aimed at curbing Palestinian rocket attacks on Israel from the town. Tutu planned to travel to the Palestinian territory to "assess the situation of victims, address the needs of survivors and make recommendations on ways and means to protect Palestinian civilians against further Israeli assaults," according to the President of the UN Human Rights Council, Luis Alfonso De Alba. Israeli officials expressed concern that the report would be biased against Israel. Tutu cancelled the trip in mid-December, saying that Israel had refused to grant him the necessary travel clearance after more than a week of discussions. However, Tutu and British academic Christine Chinkin are now due to visit the Gaza Strip via Egypt and will file a report at the September 2008 session of the Human Rights Council.

In July 2007, Tutu was declared Chair of The Elders, a group of world Leaders to contribute their wisdom, kindness, leadership and integrity to tackle some of the world's toughest problems. Tutu served in this capacity until May 2013. Upon stepping down and becoming an Honorary Elder, he said: "As Elders we should always oppose Presidents for Life. After six wonderful years as Chair, I am sad to say that it was time for me to step down." Tutu led The Elders' visit to Sudan in October 2007 – their first mission after the group was founded – to foster peace in the Darfur crisis. "Our hope is that we can keep Darfur in the spotlight and spur on governments to help keep peace in the region," said Tutu. He has also travelled with Elders delegations to Ivory Coast, Cyprus, Ethiopia, India, South Sudan and the Middle East. Tutu has been particularly involved in The Elders' initiative on child marriage, attending the Clinton Global Initiative in New York in September 2011 to launch Girls Not Brides: The Global Partnership to End Child Marriage.

In 2009, Tutu assisted in the establishing of the Solomon Islands' Truth and Reconciliation Commission, modelled after the South African body of the same name. He spoke at its official launch in Honiara on 29 April 2009, emphasising the need for forgiveness to build lasting peace. He also attended the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, and has publicly called for fossil fuel divestment, comparing it to disinvestment from apartheid-era South Africa.

In October 2010, Tutu announced his retirement from public life so that he could spend more time "at home with my family - reading and writing and praying and thinking". In November 2012, Tutu published a letter with Mairead Maguire and Adolfo Pérez Esquivel expressing support for U.S. whistleblower Bradley Manning. In July 2014, he came out in support of legalised assisted dying, stating that life shouldn't be preserved "at any cost" and that the criminalisation of assisted dying deprived the terminally ill of their "human right to dignity". In August 2017, Tutu was among ten Nobel Peace Prize laureates who urged Saudi Arabia to stop the executions of 14 young people for participating in the 2011–12 Saudi Arabian protests. In September, Tutu asked fellow Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi to halt anti-Muslim violence in Myanmar. In December, he was among those to condemn U.S. President Donald Trump's decision to officially recognise Jerusalem as Israel's capital despite opposition from the Palestinians; Tutu said that God was weeping at Trump's decision.

Beginning on his 79th birthday, Tutu entered a phased retirement from public life, starting with only one day per week in his office, until February 2011. On 23 May 2011 in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, he gave what was said to be his last major public speech outside South Africa. He honoured his commitments through May 2011 and added no more commitments.

However, he subsequently came out of retirement to give a commencement speech at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, on 13 May 2012, and gave an address at Butler University's Desmond Tutu Center in Indianapolis, Indiana, on 12 September of that year.

In 2013 he received the £1.1m ($1.6m) Templeton Prize for "his life-long work in advancing spiritual principles such as love and forgiveness".

Gish noted that by the time of apartheid's fall, Tutu had attained "worldwide respect" for his "uncompromising stand for justice and reconciliation and his unmatched integrity". According to Allen, Tutu "made a powerful and unique contribution to publicizing the antiapartheid struggle abroad", particularly in the United States. In the latter country, he was able to rise to prominence as a South African anti-apartheid Activist because—unlike Mandela and other members of the ANC—he had no links to the South African Communist Party and thus was more acceptable to Americans amid the Cold War anti-communist sentiment of the period. After the end of apartheid, Tutu became "perhaps the world's most prominent religious leader advocating gay and lesbian rights", according to Allen. Ultimately, Allen thought that perhaps Tutu's "greatest legacy" was the fact that he gave "to the world as it entered the twenty-first century an African model for expressing the nature of human community".

In December 2015, Tutu's daughter, Mpho Tutu married a woman, Marceline van Furth. Tutu was able to give a blessing for the marriage of his daughter and her partner.