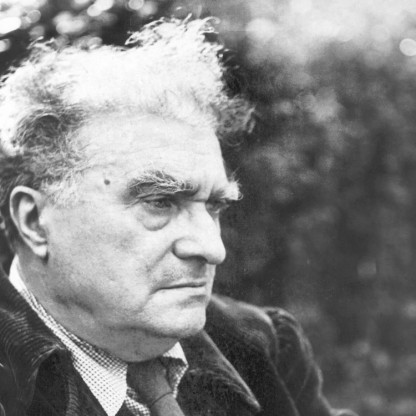

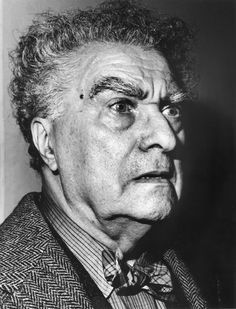

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Composer |

| Birth Day | December 18, 1922 |

| Birth Place | Paris, United States |

| Age | 98 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | November 6, 1965 |

| Birth Sign | Capricorn |

Net worth: $1.7 Million (2024)

Edgard Varese, a renowned composer in the United States, is expected to have an estimated net worth of $1.7 million by 2024. With his groundbreaking contributions to music, Varese has garnered significant recognition and financial success throughout his career. His innovative approach to composition, incorporating electronic and unconventional sounds, has captivated audiences and cemented his status as a pioneer in the field. Known for pushing the boundaries of musical experimentation, Varese's unique style has earned him a dedicated following and lucrative opportunities, ultimately contributing to his impressive net worth.

Famous Quotes:

When I was about twenty, I came across a definition of music that seemed suddenly to throw light on my gropings toward music I sensed could exist. Józef Maria Hoene-Wroński, the Polish physicist, chemist, musicologist and philosopher of the first half of the nineteenth century, defined music as 'the corporealization of the intelligence that is in sounds.' It was a new and exciting conception and to me the first that started me thinking of music as spatial—as moving bodies of sound in space, a conception I gradually made my own."

Biography/Timeline

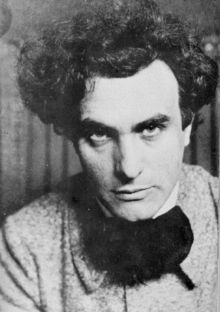

After being reclaimed by his parents in the late 1880s, in 1893 young Edgard was forced to relocate with them to Turin, Italy, in part, to live amongst his paternal relatives, since his Father was of Italian descent. It was here that he had his first real musical lessons, with the long-time Director of Turin's conservatory, Giovanni Bolzoni. In 1895, he composed his first opera, Martin Pas, which has since been lost. Now in his teen years, Varèse, influenced by his Father, an Engineer, enrolled at the Polytechnic of Turin and started studying engineering, as his Father disapproved of his interest in music, and demanded an absolute dedication to engineering studies. This conflict grew bigger and bigger, especially after the death of his mother in 1900, until in 1903 Varèse left home for Paris.

Varèse began his music studies with Vincent d'Indy (conducting) at the Schola Cantorum de Paris from 1903–05 and later began studying at the Conservatoire de Paris under Charles-Marie Widor from 1905–07. While he was in Paris, Varèse had another pivotal experience during a performance of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony at the Salle Pleyel. As the story goes, during the scherzo movement, perhaps due to the resonance of the hall, Varèse had the experience of the music breaking up and projecting in space. It was an idea that stayed with him for the rest of his life, that he would later describe as consisting of "sound objects, floating in space."

From 1904, he was a student at the Schola Cantorum (founded by pupils of César Franck), where his teachers included Albert Roussel. Afterwards, he went to study composition with Charles-Marie Widor at the Paris Conservatoire. In this period, he composed a number of ambitious orchestral works, but these were only performed by Varèse in piano transcriptions. One such work was his Rhapsodie romane, from about 1905, which was inspired by the Romanesque architecture of the cathedral of St. Philibert in Tournus. In 1907, he moved to Berlin, and in the same year, he married the Actress Suzanne Bing, with whom he had one child, a daughter. They divorced in 1913.

During these years, Varèse became acquainted with Erik Satie and Richard Strauss, as well as with Claude Debussy and Ferruccio Busoni, who particularly influenced him at the time. He also gained the friendship and support of Romain Rolland and Hugo von Hofmannsthal, whose Œdipus und die Sphinx he began setting as an opera that was never completed. On 5 January 1911, the first performance of his symphonic poem Bourgogne was held in Berlin; the only one of his early orchestral works to be properly performed in his lifetime, it caused a scandal.

After being invalided out of the French Army during World War I, he moved to the United States in December 1915.

In 1918, Varèse made his debut in America conducting the Grande messe des morts by Berlioz.

From the late 1920s to the end of the 1930s, Varèse's principal creative energies went into two ambitious projects which were never realized, and much of whose material was destroyed, though some elements from them seem to have gone into smaller works. One was a large-scale stage work called by different names at different times, but principally The One-All-Alone or Astronomer (L'Astronome). This was originally to be based on North American Indian legends; later it became a Futuristic drama of world catastrophe and instantaneous communication with the star Sirius. This second form, on which Varèse worked in Paris in 1928–1932, had a libretto by Alejo Carpentier, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes and Robert Desnos. According to Carpentier, a substantial amount of this work was written but Varèse abandoned it in favour of a new treatment in which he hoped to collaborate with Antonin Artaud. Artaud's libretto Il n'y a plus de firmament was written for Varèse's project and sent to him after he had returned to the U.S., but by this time Varèse had turned to a second huge project.

At the completion of this work, Varèse, along with Carlos Salzedo, founded the International Composers' Guild, dedicated to the performances of new compositions of both American and European composers. The ICG's manifesto in July 1921 included the statement, "[t]he present day composers refuse to die. They have realised the necessity of banding together and fighting for the right of each individual to secure a fair and free presentation of his work." In 1922, Varèse visited Berlin where he founded a similar German organisation with Busoni.

He took American citizenship in October 1927. After arriving in the USA Varèse commonly used the form 'Edgar' for his first name but reverted to 'Edgard', not entirely consistently, from the 1940s.

In 1928, when he was asked about jazz, he said it was not representative of America but instead was, "a negro product, exploited by the Jews. All of its composers here are Jews," meaning Gruenberg and Boulanger students including Copland and Blitzstein.

He was approached by music Producer Jack Skurnick resulting in EMS Recordings #401. The record was the first release on LP of Integrales, Density 21.5, Ionisation and Octandre and featured René Le Roy, flute, the Juilliard Percussion Orchestra and the New York Wind Ensemble conducted by Frederic Waldman. Ionisation had also been the first work by Varèse to be recorded in the 1930s, conducted by Nicolas Slonimsky and issued on 78rpm Columbia 4095M. Likewise, Octandre was recorded and issued on 78rpm discs in the later 1930s, complete (New Music Quarterly Recordings 1411) and as an excerpt (3rd movement, Columbia DB1791 in Volume V of their History of Music). Le Roy was the soloist also on a 1948 (78rpm) recording of Density 21.5 (New Music Recordings 1000).

In 1931, he was the best man at the wedding of his friend Nicolas Slonimsky in Paris. In 1933, while still in Paris, he wrote to the Guggenheim Foundation and Bell Laboratories in an attempt to receive a grant to develop an electronic music studio. His next composition, Ecuatorial, was completed in 1934, and contained parts for two fingerboard Theremin cellos, along with winds, percussion, and a bass singer. Anticipating the successful receipt of one of his grants, Varèse eagerly returned to the United States to realize his electronic music. Slonimsky conducted its premiere in New York on April 15, 1934.

On several occasions, Varèse speculated on the specific ways in which Technology would change music in the Future. In 1936, he predicted musical machines that would be able to perform music as soon as a Composer inputs his score. These machines would be able to play "any number of frequencies," and therefore the score of the Future would need to be "seismographic" in order to illustrate their full potential. In 1939, he expanded on this concept, declaring that with this machine "anyone will be able to press a button to release music exactly as the Composer wrote it—exactly like opening up a book." Varèse would not realize these predictions until his tape experiments in the 1950s and 60s.

Varèse's best known student was the Chinese-born Composer Chou Wen-chung, who moved to the United States, met Varèse in 1949 and assisted him in his later years. He became the executor of Varèse's estate following the composer's death. He edited and completed a number of Varèse's works. For other pupils of Varèse, See: List of music students by teacher: T to Z#Edgard Varèse.

By the early 1950s, Varèse was in dialogue with a new generation of composers, such as Pierre Boulez and Luigi Dallapiccola. When he returned to France to finalize the tape sections of Déserts, Pierre Schaeffer helped arrange for suitable facilities. The first performance of the combined orchestral and tape sound composition came as part of an ORTF broadcast concert, between pieces by Mozart and Tchaikovsky and received a hostile reaction.

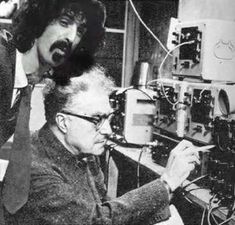

On Zappa's 15th birthday, December 21, 1955, his mother allowed him an expensive long-distance call to Varèse's home in New York City. At the time Varèse was away in Brussels, Belgium, so Zappa spoke to Varèse's wife Louise instead. Eventually Zappa and Varèse spoke on the phone, and they discussed the possibility of meeting each other. Although this meeting never took place, Zappa received a letter from Varèse. Varèse's spirit of experimentation with which he redefined the bounds of what was possible in music lived on in Zappa's long and prolific career. Zappa's final project was The Rage and the Fury, a recording of the works of Varèse. In the liner notes of his early albums, he often subtly misquoted the ICG manifesto, "The present day Composer refuses to die."

The eminent champion and Conductor of modern music, Robert Craft, recorded two LP volumes of Varèse music in 1958 and 1960 with percussion, brass, and wind sections from the Columbia Symphony Orchestra for Columbia Records (Columbia LP catalog NOS.MS6146 and MS6362). These recordings brought Varèse wide attention among Musicians and musical aficionados beyond his immediate sphere. Much of the percussion music of George Crumb is particularly owing to such Varèse works as Ionisation and Intégrales.

Varèse's emphasis on timbre, rhythm, and new technologies inspired a generation of Musicians who came of age during the 1960s and 1970s. One of Varèse's greatest fans was the American Guitarist and Composer Frank Zappa, who, upon hearing a copy of The Complete Works of Edgard Varèse, Vol. 1 became obsessed with the composer's music. The first album Zappa heard was released on LP by EMS Recordings in 1950, and included Intégrales, Density 21.5, Ionisation, and Octandre.

In 1962, he was asked to join the Royal Swedish Academy of Music, and in 1963 he received the premier Koussevitzky International Recording Award.

This second project was to be a choral symphony entitled Espace. In its original conception, the text for the chorus was to be written by André Malraux. Later, Varèse settled on a multi-lingual text of hieratic phrases to be sung by choirs situated in Paris, Moscow, Peking and New York City, synchronized to create a global radiophonic event. Varèse sought input on the text from Henry Miller, who suggests in The Air-Conditioned Nightmare that this grandiose conception—also ultimately unrealized—eventually metamorphosed into Déserts. With both these huge projects Varèse felt ultimately frustrated by the lack of electronic instruments to realize his aural visions. Nevertheless, he used some of the material from Espace in his short Étude pour espace, virtually the only work that had appeared from his pen for over ten years when it was premiered in 1947. According to Chou Wen-chung, Varèse made various contradictory revisions to Étude pour espace which made it impossible to perform again, but the 2009 Holland Festival, which offered a 'complete works' of Varèse over the weekend of 12–14 June 2009, persuaded Chou to make a new performing version (using similar brass and woodwind forces to Déserts and making use of spatialized sound projection). This was premiered at the Gashouder concert hall, Westergasfabriek, Amsterdam by Asko/Schönberg Ensemble and Cappella Amsterdam on Sunday 14 June, conducted by Peter Eötvös.

In his formative years, Varèse was greatly impressed by Medieval and Renaissance music – in his career, he founded and conducted several choirs devoted to this repertoire – as well as the music of Alexander Scriabin, Erik Satie, Claude Debussy, Hector Berlioz and Richard Strauss. There are also clear influences or reminiscences of Stravinsky's early works, specifically Petrushka and The Rite of Spring, on Arcana. He was also impressed by the ideas of Busoni, who christened him L'illustro futuro.

Varèse actively promoted performances of works by other 20th-century composers and founded the International Composers’ Guild in 1921 and the Pan-American Association of Composers in 1926.