Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | King of England |

| Birth Day | April 25, 1284 |

| Birth Place | Caernarfon Castle, British |

| Age | 735 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 21 September 1327(1327-09-21) (aged 43)\nBerkeley Castle, Gloucestershire |

| Birth Sign | Taurus |

| Reign | 7 July 1307 – 25 January 1327 |

| Coronation | 25 February 1308 |

| Predecessor | Edward I |

| Successor | Edward III |

| Burial | 20 December 1327 Gloucester Cathedral, Gloucestershire, England |

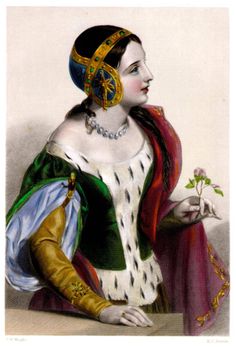

| Spouse | Isabella of France (m. 1308) |

| Issue Detail | Edward III, King of England John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall Eleanor, Countess of Guelders Joan, Queen of Scots Adam FitzRoy |

| House | Plantagenet |

| Father | Edward I, King of England |

| Mother | Eleanor, Countess of Ponthieu |

Net worth

Edward II of England, also recognized as the King of England in British history, is anticipated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M by 2024. This estimation is based on historical analyses and assessments of his wealth during his reign. Edward II's wealth was influenced by his royal position and the resources and properties under his control. While the precise figure remains subject to interpretation, considering his prominence as a monarch, it is apparent that Edward II held substantial wealth during his time as the ruler of England.

Biography/Timeline

Several plays have shaped Edward's contemporary image. Christopher Marlowe's play Edward II was first performed around 1592, and focuses on Edward's relationship with Piers Gaveston, reflecting 16th-century concerns about the relationships between monarchs and their favourites. Marlowe presents Edward's death as a murder, drawing parallels between the killing and martyrdom; although Marlowe does not describe the actual nature of Edward's murder in the script, it has usually been performed following the tradition that Edward was killed with a red-hot poker. The character of Edward in the play, who has been likened to Marlowe's contemporaries James VI of Scotland and Henry III of France, may have influenced william Shakespeare's portrayal of Richard II. In the 17th century, the Playwright Ben Jonson picked up the same theme for his unfinished work, Mortimer His Fall.

Historians in the 16th and 17th centuries focused on Edward's relationship with Gaveston, drawing comparisons between Edward's reign and the events surrounding the relationship of the Duc d'Épernon and Henry III of France, and between the Duke of Buckingham and Charles I. In the first half of the 19th century, popular historians such as Charles Dickens and Charles Knight popularised Edward's life with the Victorian public, focusing on the King's relationship with his favourites and, increasingly, alluding to his possible homosexuality. From the 1870s onwards, however, open academic discussion of Edward's sexuality was circumscribed by changing English values. By the start of the 20th century, English schools were being advised by the government to avoid overt discussion of Edward's personal relationships in history lessons. Views on Edward's sexuality have continued to develop over the years.

Edward's life has also been used in a wide variety of other media. In the Victorian era, the painting Edward II and Piers Gaveston by Marcus Stone strongly hinted at a homosexual relationship between the pair, while avoiding making this aspect explicit. It was initially shown at the Royal Academy in 1872, but was marginalised in later decades as the issue of homosexuality became more sensitive. More recently, the Director David Bintley used Marlowe's play as the basis for the ballet Edward II, first performed in 1995; the music from the ballet forms a part of Composer John McCabe's symphony Edward II, produced in 2000. Novels such as John Penford's 1984 The Gascon and Chris Hunt's 1992 Gaveston have focused on the sexual aspects of Edward and Gaveston's relationship, while Stephanie Merritt's 2002 Gaveston transports the story into the 20th century.

By the end of the 19th century, more administrative records from the period had become available to historians such as william Stubbs, Thomas Tout and J. C. Davies, who focused on the development of the English constitutional and governmental system during his reign. Although critical of what they regarded as Edward's inadequacies as a king, they also emphasised the growth of the role of parliament and the reduction in personal royal authority under Edward II, which they perceived as positive developments. During the 1970s the historiography of Edward's reign shifted away from this model, supported by the further publishing of records from the period in the last quarter of the 20th century. The work of Jeffrey Denton, Jeffrey Hamilton, John Maddicott and Seymour Phillips re-focused attention on the role of the individual Leaders in the conflicts. With the exceptions of Hilda Johnstone's work on Edward's early years, and Natalie Fryde's study of Edward's final years, the focus of the major historical studies for several years was on the leading magnates rather than Edward himself, until substantial biographies of the King were published by Roy Haines and Seymour Phillips in 2003 and 2011.

The filmmaker Derek Jarman adapted the Marlowe play into a film in 1991, creating a postmodern pastiche of the original, depicting Edward as a strong, explicitly homosexual leader, ultimately overcome by powerful enemies. In Jarman's version, Edward finally escapes captivity, following the tradition in the Fieschi letter. Edward's current popular image was also shaped by his contrasting appearance in Mel Gibson's 1995 film Braveheart, where he is portrayed as weak and implicitly homosexual, wearing silk clothes and heavy makeup, shunning the company of women and incapable of dealing militarily with the Scots. The film received extensive criticism, both for its historical inaccuracies and for its negative portrayal of homosexuality.

No chronicler for this period is entirely trustworthy or unbiased, often because their accounts were written to support a particular cause, but it is clear that most contemporary chroniclers were highly critical of Edward. The Polychronicon, Vita Edwardi Secundi, Vita et Mors Edwardi Secundi and the Gesta Edwardi de Carnarvon for Example all condemned the King's personality, habits and choice of companions. Other records from his reign show criticism of Edward by his contemporaries, including the Church and members of his own household. Political songs were written about him, complaining about his failure in war and his oppressive government. Later in the 14th century, some chroniclers, such as Geoffrey le Baker and Thomas Ringstead, rehabilitated Edward, presenting him as a martyr and a potential saint, although this tradition died out in later years.