Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Mayor of Aldeburgh |

| Birth Day | June 09, 1836 |

| Birth Place | Whitechapel, British |

| Age | 183 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 17 December 1917(1917-12-17) (aged 81)\nAldeburgh, Suffolk, England |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

| Education | Studied privately with physicians in London hospitals Society of Apothecaries |

| Known for | First woman to openly gain a medical qualification in Britain Creating a medical school for women |

| Relatives | James Anderson (husband) Louisa Garrett Anderson (daughter) Alan Garrett Anderson (son) Millicent Garrett Fawcett (sister) Newson Garrett (father) |

| Profession | Physician |

| Institutions | New Hospital for Women London School of Medicine for Women |

Net worth

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, also known as the Mayor of Aldeburgh in British, is projected to have a net worth between $100,000 and $1,000,000 in the year 2024. As a prominent figure in her community, Elizabeth has undoubtedly earned her wealth through years of hard work and accomplishments. Her dedication to public service and her role as a successful mayor has likely contributed to her financial success. With such a considerable net worth, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson garners both admiration and respect from her constituents and serves as an inspiration for aspiring community leaders.

Biography/Timeline

Elizabeth Garrett was born on 9 June 1836 in Whitechapel, London, the second of eleven children of Newson Garrett (1812–1893), from Leiston, Suffolk, and his wife, Louisa née Dunnell (1813–1903), from London.

Later in life, Garrett recalled the stupidity of her teachers there, though her schooling there did help establish a love of reading. Her main complaint about the school was the lack of science and mathematics instruction. Her reading matter included Tennyson, Wordsworth, Milton, Coleridge, Trollope, Thackeray and George Eliot. Elizabeth and Louie were known as “the bathing Garretts”, as their father had insisted they be allowed a hot bath once a week. However, they made what were to be lifelong friends there. When they finished in 1851, they were sent on a short tour abroad, ending with a memorable visit to the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, London.

The Garretts lived in a square Georgian house opposite the church in Aldeburgh until 1852. Newson's malting Business expanded and five more children were born, Edmund (1840), Alice (1842), Millicent (1847), who was to become a leader in the constitutional campaign for women's suffrage, Sam (1850), Josephine (1853) and George (1854). By 1850, Newson was a prosperous businessman and was able to build Alde House, a mansion on a hill behind Aldeburgh. A “by-product of the industrial revolution”, Garrett grew up in an atmosphere of “triumphant economic pioneering” and the Garrett children were to grow up to become achievers in the professional classes of late-Victorian England. Garrett was encouraged to take an interest in local politics and, contrary to practices at the time, was allowed the freedom to explore the town with its nearby salt-marshes, beach and the small port of Slaughden with its boatbuilders' yards and sailmakers' lofts.

After this formal education, Garrett spent the next nine years tending to domestic duties, but she continued to study Latin and arithmetic in the mornings and also read widely. Her sister Millicent recalled Garrett's weekly lectures, “Talks on Things in General”, when her younger siblings would gather while she discussed politics and current affairs from Garibaldi to Macaulay's History of England. In 1854, when she was eighteen, Garrett and her sister went on a long visit to their school friends, Jane and Anne Crow, in Gateshead where she met Emily Davies, the early feminist and Future co-founder of Girton College, Cambridge. Davies was to be a lifelong friend and confidante, always ready to give sound advice during the important decisions of Garrett’s career. It may have been in the English Woman's Journal, first issued in 1858, that Garrett first read of Elizabeth Blackwell, who had become the first female Doctor in the United States in 1849. When Blackwell visited London in 1859, Garrett travelled to the capital. By then, her sister Louie was married and living in London. Garrett joined the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women, which organised Blackwell's lectures on "Medicine as a Profession for Ladies" and set up a private meeting between Garrett and the Doctor. It is said that during a visit to Alde House around 1860, one evening while sitting by the fireside, Garrett and Davies selected careers for advancing the frontiers of women's rights; Garrett was to open the medical profession to women, Davies the doors to a university education for women, while 13-year-old Millicent was allocated politics and votes for women. At first Newson was opposed to the radical idea of his daughter becoming a physician but came round and agreed to do all in his power, both financially and otherwise, to support Garrett.

After an initial unsuccessful visit to leading doctors in Harley Street, Garrett decided to first spend six months as a surgery nurse at Middlesex Hospital, London in August 1860. On proving to be a good nurse, she was allowed to attend an outpatients' clinic, then her first operation. She unsuccessfully attempted to enroll in the hospital's Medical School but was allowed to attend private tuition in Latin, Greek and materia medica with the hospital's apothecary, while continuing her work as a nurse. She also employed a tutor to study anatomy and physiology three evenings a week. Eventually she was allowed into the dissecting room and the chemistry lectures. Gradually, Garrett became an unwelcome presence among the male students, who in 1861 presented a memorial to the school against her admittance as a fellow student, despite the support she enjoyed from the administration. She was obliged to leave the Middlesex Hospital but she did so with an honours certificate in chemistry and materia medica. Garrett then applied to several medical schools, including Oxford, Cambridge, Glasgow, Edinburgh, St Andrews and the Royal College of Surgeons, all of which refused her admittance.

A companion to her in this struggle was the lesser known Dr Sophia Jex-Blake. Whilst both are considered "outstanding" medical figures of the late 19th century, Garrett was able to obtain her credentials by way of a "side door" through a loophole in admissions at the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries. Having privately obtained a certificate in anatomy and physiology, she was admitted in 1862 by the Society of Apothecaries who, as a condition of their charter, could not legally exclude her on account of her sex. She continued her battle to qualify by studying privately with various professors, including some at the University of St Andrews, the Edinburgh Royal Maternity and the London Hospital Medical School.

Though she was now a licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries, as a woman, Garrett could not take up a medical post in any hospital. So in late 1865, Garrett opened her own practice at 20 Upper Berkeley Street, London. At first, patients were scarce but the practice gradually grew. After six months in practice, she wished to open an outpatients dispensary, to enable poor women to obtain medical help from a qualified practitioner of their own gender. In 1865, there was an outbreak of cholera in Britain, affecting both rich and poor, and in their panic, some people forgot any prejudices they had in relation to a female physician. The first death due to cholera occurred in 1866, but by then Garrett had already opened St Mary's Dispensary for Women and Children, at 69 Seymour Place. In the first year, she tended to 3,000 new patients, who made 9,300 outpatient visits to the dispensary. On hearing that the Dean of the faculty of Medicine at the University of Sorbonne, Paris was in favour of admitting women as medical students, Garrett studied French so that she could apply for a medical degree, which she obtained in 1870 after some difficulty.

Garrett Anderson was also active in the women's suffrage movement. In 1866, Garrett Anderson and Davies presented petitions signed by more than 1,500 asking that female heads of household be given the vote. That year, Garrett Anderson joined the first British Women's Suffrage Committee. She was not as active as her sister, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, though Garrett Anderson became a member of the Central Committee of the National Society for Women's Suffrage in 1889. After her husband's death in 1907, she became more active. As mayor of Aldeburgh, she gave speeches for suffrage, before the increasing militant activity in the movement led to her withdrawal in 1911. Her daughter Louisa, also a physician, was more active and more militant, spending time in prison in 1912 for her suffrage activities.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson once remarked that “a Doctor leads two lives, the professional and the private, and the boundaries between the two are never traversed”. In 1871, she married James George Skelton Anderson (d. 1907) of the Orient Steamship Company co-owned by his uncle Arthur Anderson, but she did not give up her medical practice. She had three children, Louisa (1873–1943), Margaret (1874–1875), who died of meningitis, and Alan (1877–1952). Louisa also became a pioneering Doctor of Medicine and feminist Activist.

In 1873 she gained membership of the British Medical Association and remained the only female member for 19 years, due to the Association's vote against the admission of further women – "one of several instances where Garrett, uniquely, was able to enter a hitherto all male medical institution which subsequently moved formally to exclude any women who might seek to follow her." In 1897, Garrett Anderson was elected President of the East Anglian branch of the British Medical Association.

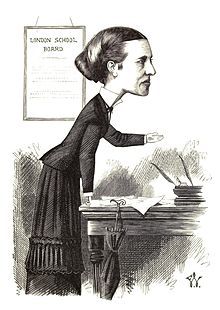

Garrett Anderson worked steadily at the development of the New Hospital for Women, and (from 1874) at the creation of the London School of Medicine for Women, where she served as its dean. Both institutions have since been handsomely and suitably housed and equipped, the New Hospital for Women (in the Euston Road) for many years being worked entirely by medical women, and the schools (in Hunter Street, WC1) having over 200 students, most of them preparing for the medical degree of London University (the present-day University College London), which was opened to women in 1877.

They retired to Aldeburgh in 1902, moving to Alde House in 1903, after the death of Elizabeth’s mother. Skelton died of a stroke in 1907. She enjoyed a happy marriage and in later life, devoted time to Alde House, gardening, and travelling with younger members of the extended family.

On 9 November 1908, she was elected mayor of Aldeburgh, the first female mayor in England. Her father was mayor in 1889.

She died in 1917 and is buried in the churchyard of St Peter and St Paul's Church, Aldeburgh.

The New Hospital for Women was renamed the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital in 1918 and amalgamated with the Obstetric Hospital in 2001 to form the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Obstetric Hospital before relocating to become the University College Hospital Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Wing at UCH.

The former Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital buildings are incorporated into the new National Headquarters for the public Service trade union UNISON. The Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Gallery, a permanent installation set within the restored hospital building, uses a variety of media to set the story of Garrett Anderson, her hospital, and women's struggle to achieve equality in the field of Medicine within the wider framework of 19th and 20th century social history.