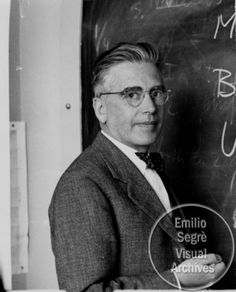

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Physicist |

| Birth Day | January 30, 1905 |

| Birth Place | Tivoli, Italy, American |

| Age | 115 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 22 April 1989(1989-04-22) (aged 84)\nLafayette, California, United States of America |

| Birth Sign | Aquarius |

| Citizenship | Italy (1905–89) United States (1944–89) |

| Alma mater | Sapienza University of Rome |

| Known for | Discovery of antiproton, technetium, and astatine |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physics (1959) |

| Institutions | Los Alamos National Laboratory University of California, Berkeley University of Palermo Sapienza University of Rome Columbia University |

| Doctoral advisor | Enrico Fermi |

| Doctoral students | Basanti Dulal Nagchaudhuri Thomas Ypsilantis Herbert York |

Net worth

Emilio Segrè, the renowned physicist hailing from Italy but ultimately settling in the United States, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million by 2024. Throughout his illustrious career, Segrè made significant contributions to the field of nuclear and particle physics, particularly with his involvement in discovering the antiproton. He was also a key contributor to the Manhattan Project and the development of the atomic bomb. Known for his brilliant mind and scientific achievements, Segrè's net worth is a reflection of his transformative impact on the world of physics.

Biography/Timeline

Emilio Gino Segrè was born into a Sephardic Jewish family in Tivoli, near Rome, on 1 February 1905, the son of Giuseppe Segrè, a businessman who owned a paper mill, and Amelia Susanna Treves. He had two older brothers, Angelo and Marco. His uncle, Gino Segrè, was a law professor. He was educated at the ginnasio in Tivoli and, after the family moved to Rome in 1917, the ginnasio and liceo in Rome. He graduated in July 1922 and enrolled in the University of Rome La Sapienza as an engineering student.

In 1927, Segrè met Franco Rasetti, who introduced him to Enrico Fermi. The two young physics professors were looking for talented students. They attended the Volta Conference at Como in September 1927, where Segrè heard lectures from notable physicists including Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Robert Millikan, Wolfgang Pauli, Max Planck and Ernest Rutherford. Segrè then joined Fermi and Rasetti at their laboratory in Rome. With the help of the Director of the Institute of Physics, Orso Mario Corbino, Segrè was able to transfer to physics, and, studying under Fermi, earned his laurea degree in July 1928, with a thesis on "Anomalous Dispersion and Magnetic Rotation".

After a stint in the Italian Army from 1928 to 1929, during which he was a commissioned as a second lieutenant in the antiaircraft artillery, Segrè returned to the laboratory on Via Panisperna. He published his first article, which summarised his thesis, "On anomalous dispersion in mercury and in lithium", jointly with Edoardo Amaldi in 1928, and another article with him the following year on the Raman effect.

In 1930, Segrè began studying the Zeeman effect in certain Al Kaline metals. When his progress stalled because the diffraction grating he required to continue was not available in Italy, he wrote to four laboratories elsewhere in Europe asking for assistance and received an invitation from Pieter Zeeman to finish his work at Zeeman's laboratory in Amsterdam. Segrè was awarded a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship and, on Fermi's advice, elected to use it to study under Otto Stern in Hamburg. Working with Otto Frisch on space quantization produced results that apparently did not agree with the current theory; but Isidor Isaac Rabi showed that theory and experiment were in agreement if the nuclear spin of potassium was +1/2.

After marrying, Segrè sought a stable job and became professor of physics and Director of the Physics Institute at the University of Palermo. He found the equipment there primitive and the library bereft of modern physics literature, but his colleagues at Palermo included the mathematicians Michele Cipolla and Michele De Franchis, the mineralogist Carlo Perrier and the Botanist Luigi Montemartini. In 1936 he paid a visit to Ernest O. Lawrence's Berkeley Radiation Laboratory, where he met Edwin McMillan, Donald Cooksey, Franz Kurie, Philip Abelson and Robert Oppenheimer. Segrè was intrigued by the radioactive scrap metal that had once been part of the laboratory's cyclotron. In Palermo, this was found to contain a number of radioactive isotopes. In February 1937, Lawrence sent him a molybdenum strip that was emitting anomalous forms of radioactivity. Segrè enlisted Perrier's help to subject the strip to careful chemical and theoretical analysis, and they were able to prove that some of the radiation was being produced by a previously unknown element. In 1947 they named it technetium, as it was the first artificially synthesized chemical element.

In June 1938, Segrè paid a summer visit to California to study the short-lived isotopes of technetium, which did not survive being mailed to Italy. While Segrè was en route, Benito Mussolini's fascist government passed racial laws barring Jews from university positions. As a Jew, Segrè was now rendered an indefinite émigré. The Czechoslovakian crisis prompted Segrè to send for Elfriede and Claudio, as he now feared that war in Europe was inevitable. In November 1938 and February 1939 they made quick trips to Mexico to exchange their tourist visas for immigration visa. Both Segrè and Elfriede held grave fears for the fate of their parents in Italy and Germany.

In the late 1940s, many academics left the University of California, lured away by higher-salary offers and by the University's peculiar loyalty oath requirement. Segrè chose to take the oath and stay, but this did not allay suspicions about his loyalty. Luis Alvarez was incensed that Amaldi, Fermi, Pontecorvo, Rasetti and Segrè had chosen to pursue patent claims against the United States for their pre-war discoveries and told Segrè to let him know when Pontecorvo wrote from Russia. He also clashed with Lawrence over the latter's plan to create a rival nuclear-weapons laboratory to Los Alamos in Livermore, California, in order to develop the hydrogen bomb, a weapon that Segrè felt would be of dubious utility.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and the subsequent United States declaration of war upon Italy rendered Segrè an enemy alien and cut him off from communication with his parents. Physicists began leaving the Radiation Laboratory to do war work, and Raymond T. Birge asked him to teach classes to the remaining students. This provided a useful supplement to Segrè's income, and he established important friendships and professional associations with some of these students, who included Owen Chamberlain and Clyde Wiegand.

In late 1942, Oppenheimer asked Segrè to join the Manhattan Project at its Los Alamos Laboratory. Segrè became the head of the laboratory's P-5 (Radioactivity) Group, which formed part of Robert Bacher's P (Experimental Physics) Division. For security reasons, he was given the cover name of Earl Seaman. He moved to Los Alamos with his family in June 1943.

Segrè's group set up its equipment in a disused Forest Service cabin in the Pajarito Canyon near Los Alamos in August 1943. His group's task was to measure and catalog the radioactivity of various fission products. An important line of research was determining the degree of isotope enrichment achieved with various samples of enriched uranium. Initially, the tests using mass spectrometry, used by Columbia University, and neutron assay, used by Berkeley, gave different results. Segrè studied Berkeley's results and could find no error, while Kenneth Bainbridge likewise found no fault with New York's. However, analysis of another sample showed close agreement. Higher rates of spontaneous fission were observed at Los Alamos, which Segrè's group concluded were due to cosmic rays, which were more prevalent at Los Alamos due to its high altitude.

In June 1944, Segrè was summoned into Oppenheimer's office and informed that while his father was safe, his mother had been rounded up by the Nazis in October 1943. Segrè never saw either of his parents again. His father died in Rome in October 1944. In late 1944, Segrè and Elfriede became naturalized citizens of the United States. His group, now designated R-4, was given responsibility for measuring the gamma radiation from the Trinity nuclear test in July 1945. The blast damaged or destroyed most of the experiments, but enough data was recovered to measure the gamma rays.

In August 1945, a few days before the surrender of Japan and the end of World War II, Segrè received an offer from Washington University in St. Louis of an associate professorship with a salary of US$5,000 (equivalent to $68,000 in 2017). The following month, the University of Chicago also made him an offer. After some prompting, Birge offered $6,500 and a full professorship, which Segrè decided to accept. He left Los Alamos in January 1946 and returned to Berkeley.

After turning down offers from IBM and the Brookhaven National Laboratory, Segrè returned to Berkeley in 1952. He moved his family from Berkeley to nearby Lafayette, California, in 1955. Working with Chamberlain and others, he began searching for the antiproton, a subatomic antiparticle of the proton. The antiparticle of the electron, the positron had been predicted by Paul Dirac in 1931 and then discovered by Carl D. Anderson in 1932. By analogy, it was now expected that there would be an antiparticle corresponding to the proton, but no one had found one, and even in 1955 some Scientists doubted that it existed. Using Lawrence's Bevatron set to 6 GeV, they managed to detect conclusive evidence of antiprotons. Chamberlain and Segrè were awarded the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physics for their discovery. This was controversial, because Clyde Wiegand and Thomas Ypsilantis were co-authors of the same article, but did not share the prize.

Segrè served on the University's powerful Budget Committee from 1961 to 1965 and was chairman of the Physics Department from 1965 to 1966. He supported Teller's successful bid to separate the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory from the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory in 1970. He was one of the trustees of Fermilab from 1965 to 1968. He attended its inauguration with Laura Fermi in 1974. During the 1950s, Segrè edited Fermi's papers. He later published a biography of Fermi, Enrico Fermi: Physicist (1970). He published his own lecture notes as From X-rays to Quarks: Modern Physicists and Their Discoveries (1980) and From Falling Bodies to Radio Waves: Classical Physicists and Their Discoveries (1984). He also edited the Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science from 1958 to 1977 and wrote an autobiography, A Mind Always in Motion (1993), which was published posthumously.

Elfriede died in October 1970, and Segrè married Rosa Mines in February 1972. That year he reached the University of California's compulsory retirement age. He continued teaching the history of physics. In 1974 he returned to the University of Rome as a professor, but served only a year before reaching the mandatory retirement age. Segrè died from a heart attack at the age of 84 while out walking near his home in Lafayette. Active as a Photographer, Segrè took many photos documenting events and people in the history of modern science. After his death Rosa donated many of his photographs to the American Institute of Physics, which named its photographic archive of physics history in his honor. The collection was bolstered by a subsequent bequest from Rosa after her death from an accident in Tivoli in 1997.

Unhappy with his deteriorating relationships with his colleagues and with the poisonous political atmosphere at Berkeley caused by the loyalty oath controversy, Segrè accepted a job offer from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. The courts ultimately resolved the patent claims in the Italian scientists' favour in 1953, awarding them US$400,000 (equivalent to $3,700,000 in 2017) for the patents related to generating neutrons, which worked out to about $20,000 after legal costs. Kennedy, Seaborg, Wahl and Segrè were subsequently awarded the same amount for their discovery of plutonium, which came to $100,000 after being divided four ways, there being no legal fees this time.

At the Berkeley Radiation Lab, Lawrence offered Segrè a job as a research assistant—a relatively lowly position for someone who had discovered an element—for US$300 (equivalent to $5,300 in 2017) a month for six months. When Lawrence learned that Segrè was legally trapped in California, he reduced Segrè's salary to $116 a month. Working with Glenn Seaborg, Segrè isolated the metastable isotope technetium-99m. Its properties made it ideal for use in nuclear Medicine, and it is now used in about 10 million medical diagnostic procedures annually. Segrè went looking for element 93, but did not find it, as he was looking for an element chemically akin to rhenium instead of a rare-earth element, which is what element 93 was. Working with Alexander Langsdorf, Jr., and Chien-Shiung Wu, he discovered xenon-135, which later became important as a nuclear poison in nuclear reactors.