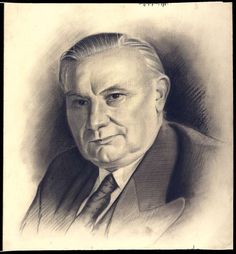

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | British statesman |

| Birth Day | March 09, 1881 |

| Birth Place | Winsford, Somerset, British |

| Age | 138 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 14 April 1951(1951-04-14) (aged 70)\nLondon, England, UK |

| Birth Sign | Aries |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Deakin |

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouse(s) | Florence Townley (19??-1951; his death); (died 1968) 1 child |

Net worth: $400,000 (2024)

Ernest Bevin, a renowned British statesman, is anticipated to have a net worth of $400,000 by the year 2024. Bevin was widely recognized for his significant contributions to British politics and held influential positions during his career. Serving as the Minister of Labour and National Service during World War II, he played a pivotal role in mobilizing the British workforce for war efforts. Bevin's extraordinary leadership skills and determination enabled him to establish himself as a prominent figure in British politics. Despite being born into a humble background, his dedication and commitment propelled him to great heights, leaving a lasting impact on the nation.

Famous Quotes:

"I suppose you will miss Sir Stafford, sir."

Attlee fixed him with his eye: "Did you know Ernie Bevin?"

"I have met him, sir," Phillips replied.

"There's the man I miss."

Biography/Timeline

The Emergency Powers (Defence) Act gave Bevin complete control over the labour force and the allocation of manpower, and he was determined to use this unprecedented authority not just to help win the war but also to strengthen the bargaining position of trade unions in the postwar Future. Bevin once quipped: "They say Gladstone was at the Treasury from 1860 until 1930. I'm going to be at the Ministry of Labour from 1940 until 1990." The industrial settlement he introduced remained largely unaltered by successive postwar administrations until the reforms of Margaret Thatcher's government in the early 1980s.

Bevin was born in the village of Winsford in Somerset, England, to Diana Bevin who, since 1877, had described herself as a widow. His father is unknown. After his mother's death in 1889, the young Bevin lived with his half-sister's family, moving to Copplestone in Devon. He had little formal education, having briefly attended two village schools and then Hayward's School, Crediton, starting in 1890 and leaving in 1892.

He later recalled being asked as a child to read the newspaper aloud for the benefit of adults in his family who were illiterate. At the age of eleven, he went to work as a labourer, then as a lorry driver in Bristol, where he joined the Bristol Socialist Society. In 1910 he became secretary of the Bristol branch of the Dock, Wharf, Riverside and General Labourers' Union, and in 1914 he became a national organiser for the union.

Bevin married Florence Townley, daughter of a wine taster at a Bristol wine merchants. They had one child, a daughter, Queenie (1914-2000). Florence Bevin would be appointed Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in 1952.

Bevin had no great faith in parliamentary politics, but had nevertheless been a member of the Labour Party from the time of its formation, and unsuccessfully fought Bristol Central at the 1918 General Election, being defeated by the Coalition Conservative Thomas Inskip. He had poor relations with the first Labour Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald, and was not surprised when MacDonald formed a National Government with the Conservatives during the economic crisis of 1931, for which MacDonald was expelled from the Labour Party. At the 1931 general election, Bevin was persuaded by the remaining Leaders of the Labour Party to contest Gateshead, on the understanding that if successful he would remain as general secretary of the TGWU. The National Government landslide resulted in Gateshead being lost by a large margin to the Liberal National Thomas Magnay.

In 1922 Bevin was one of the founding Leaders of the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU), which soon became Britain's largest trade union. Upon his election as the union's general secretary, he became one of country's leading labour Leaders, and their strongest advocate within the Labour Party. Politically, he was on the right-wing of the Labour Party, strongly opposed to communism and direct action—allegedly partly due to anti-Semitic paranoia and seeing communism as a "Jewish plot" against Britain. He took part in the British General Strike in 1926, but without enthusiasm.

During the 1930s, with the Labour Party split and weakened, Bevin co-operated with the Conservative-dominated government on practical issues. But during this period he became increasingly involved in foreign policy. He was a firm opponent of fascism and of British appeasement of the fascist powers. In 1935, arguing that Italy should be punished by sanctions for her recent invasion of Abyssinia, he made a blistering attack on the pacifists in the Labour Party, accusing the Labour leader George Lansbury at the Party Conference of "hawking his conscience around" asking to be told what to do with it.

Lansbury resigned and was replaced as leader by his deputy Clement Attlee, who along with Lansbury and Stafford Cripps had been one of only three former Labour Ministers to be re-elected under that party label at the General Election in 1931. After the November 1935 General Election Herbert Morrison, newly returned to Parliament, challenged Attlee for the leadership but was defeated. In later years Bevin gave Attlee (whom he privately referred to as "little Clem") staunch support, especially in 1947 when Morrison and Cripps led further intrigue against Attlee.

Bevin was a trade unionist who believed in getting material benefits for his members through direct negotiations, with strike action to be used as a last resort. During the late Thirties, for instance, Bevin helped to instigate a successful campaign by the TUC to extend paid holidays to a wider proportion of the workforce. This culminated in the Holidays with Pay Act of 1938, which extended entitlement to paid holidays to about 11 million workers by June 1939.

In 1940 Winston Churchill formed an all-party coalition government to run the country during the crisis of World War II. Churchill was impressed by Bevin's opposition to trade-union pacifism and his appetite for work (according to Churchill, Bevin was by 'far the most distinguished man that the Labour Party have thrown up in my time'), and appointed Bevin to the position of Minister for Labour and National Service. As Bevin was not actually an MP at the time, to remove the resulting constitutional Anomaly, a parliamentary position was hurriedly found for him and Bevin was elected unopposed to the House of Commons as Member of Parliament (MP) for the London constituency of Wandsworth Central.

In 1945, Bevin advocated the creation of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, saying in the House of Commons that "There should be a study of a house directly elected by the people of the world to whom the nations are accountable."

Bevin was infuriated by attacks on British troops carried out by the more extreme of the Jewish militant groups, the Irgun and Lehi, commonly known as the Stern Gang. The Haganah carried out less direct attacks, until the King David Hotel bombing, after which it restricted itself to illegal immigration activities. According to declassified British intelligence files, the Irgun and Lehi plotted to assassinate Bevin himself in 1946.

In December 1947 Bevin hoped (in vain) that the USA would support Britain’s “strategic, political and economic position in the Middle East”. In May 1950 Bevin told the London meeting of foreign ministers that “the United States authorities had recently seemed disposed to press us to adopt a greater measure of economic integration with Europe than we thought wise” (he was referring to the Schuman Plan to set up the European Coal and Steel Community). In May 1950 he said that because of links with USA and the Commonwealth Britain was “different in character from other European nations and fundamentally incapable of wholehearted integration with them”.

His health failing, Bevin reluctantly allowed himself to be moved to become Lord Privy Seal in March 1951. "I am neither a Lord, nor a Privy, nor a Seal", he is said to have commented. He died the following month, still holding the key to his red box. His ashes are buried in Westminster Abbey.

When, on Stafford Cripps's death in 1952, Attlee (by this time Leader of the Opposition) was invited to broadcast a tribute by the BBC, he was looked after by announcer Frank Phillips. After the broadcast, Phillips took Attlee to the hospitality room for a drink and in order to make conversation said:

Britain was still closely allied to France and both countries continued to be treated as major partners at international summits alongside the USA and USSR until 1960. Broadly speaking, all this remained Britain's foreign policy until the late 1950s, when the humiliation of the 1956 Suez Crisis and the economic revival of continental Europe, now united as the "Common Market", caused a reappraisal.

The cost of rebuilding necessitated austerity at home in order to maximise export earnings, while Britain's colonies and other client states were required to keep their reserves in pounds as "sterling balances". Additional funds—that did not have to be repaid—came from the Marshall Plan in 1948-50, which also required Britain to modernize its Business practices and remove trade barriers.

However, Charmley dismisses the concerns of contemporaries such as Charles Webster and Lord Cecil of Chelwood that Bevin, a man of very strong personality, was “in the hands of his officials”. Charmley argues that much of Bevin's success came because he shared the views of those officials: his earlier career had left him with an intense dislike of communists, whom he regarded as workshy intellectuals whose attempts to infiltrate trade unions were to be resisted. His former Private Secretary Oliver Harvey thought Bevin’s staunchly anti-Soviet policy was what Eden’s would have been had he not been hamstrung, as at Potsdam, by Churchill’s occasional susceptibility to Stalin’s flattery, whilst Cadogan thought Bevin “pretty sound on the whole”.