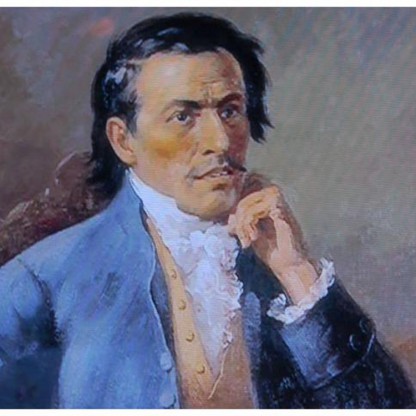

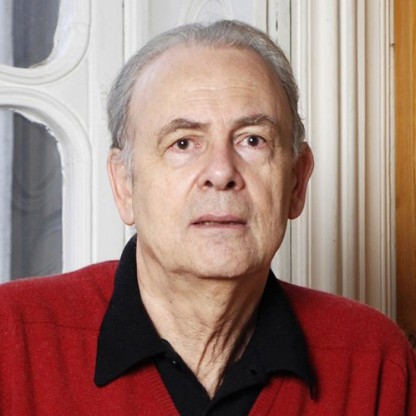

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Writer & Medical Pioneer |

| Birth Day | February 21, 1747 |

| Birth Place | Quito, Spanish Empire, Ecuadorian |

| Age | 272 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | December 28, 1795(1795-12-28) (aged 48)\n Quito, Spanish Empire |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Occupation | Writer, lawyer, physician |

Net worth

Eugenio Espejo, renowned as a prominent writer and medical pioneer in Ecuadorian history, is anticipated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in 2024. Espejo's remarkable contributions to literature and his groundbreaking advancements in the field of medicine have certainly played a pivotal role in shaping his financial success. Along with his literary prowess, Espejo's achievements as a medical professional have earned him great recognition and respect throughout Ecuador. As an influential figure in both disciplines, his net worth reflects the value and impact of his incredible work.

Biography/Timeline

The Royal Audiencia of Quito (or Presidency of Quito) was established as part of the Spanish State by Philip II of Spain on August 29, 1563. It was a court of the Spanish Crown with jurisdiction over certain territories of the Viceroyalty of Peru (and later the Viceroyalty of New Granada) that now constitute Ecuador and parts of Peru, Colombia and Brazil. The Royal Audiencia was created to strengthen administrative control over those territories and to rule the relations between whites and the natives. Its capital was the city of Quito.

He was baptized Francisco Javier Eugenio de Santa Cruz y Espejo in the El Sagrario parish on February 21, 1747. According to most historians, his father was Luis de la Cruz Chuzhig, a Quichua Indian from Cajamarca, who arrived in Quito as an assistant to the priest and physician José del Rosario, and his mother was Maria Catalina Aldás, a mulatta native to Quito. However, some historians, especially Carlos Freile Granizo, argue that contemporary documents imply that Espejo's mother was white; for instance, his parents' marriage was recorded in the book for white marriages (as they were deemed as criollos), and the birth certificates of Espejo and his siblings were entered in the same book.

Espejo had two younger siblings, Juan Pablo and María Manuela. Juan Pablo was born in 1752; he studied with the Dominicans and served as a priest in various parts of the Audiencia of Quito. María Manuela was born in 1753, and after the death of her parents she came to be cared for by her brother Eugenio. Despite his family's somewhat unstable economic situation, Espejo had a good education. He instructed himself in Medicine by working alongside his father at the Hospital de la Misericordia. According to Espejo, he learned "by experience, which cannot be known without studying with pen in hand."

Overcoming racial discrimination, he graduated from medical school on July 10, 1767, and shortly afterwards graduated in jurisprudence and canon law (having studied law under Dr. Ramón Yépez from 1780 to 1793). On August 14, 1772, he asked for permission to practice Medicine in Quito, and it was granted on November 28, 1772. After that, no information exists about Espejo's whereabouts until 1778, when he wrote a somewhat polemical sermon.

Between 1772 and 1779, Espejo provoked the colonial authorities, who regarded him as responsible for several satirical and mocking posters. These posters were attached to the doors of churches and other buildings, and their anonymous author tended to attack the colonial authorities, the clergy or any other subject he deemed convenient. Although no surviving posters have been found, evidence from comments Espejo made in his writings suggests that he wrote them.

Beginning in 1779, Espejo continued writing satires against the government of the Audiencia, stirred by the condition of society. In June 1780, Espejo wrote Marco Porcio Catón (Marcus Porcius Cato), Once again, Espejo used a pseudonym, "Moisés Blancardo." In this work, a parodied censor's response to the Nuevo Luciano, he scorned the notions and ideas of its critics. In 1781 he wrote La ciencia blancardina, which he referred to as the second part of Nuevo Luciano, as an answer to the criticism of a Mercedarian priest from Quito. Because of his works, by 1783 he was labeled as "restive and subversive." To get rid of him, the authorities named him head physician for the scientific expedition of Francisco de Requena to the Pará and Marañon rivers to set the limits of the Audiencia. Espejo tried to decline the appointment, and after that failed, he tried unsuccessfully to flee. His arrest order details one of the few remaining physical descriptions of him. Captured, he was sent back as a "criminal of serious offense," but he was not prosecuted and suffered no significant consequences.

In 1780, in his first discussion of purely religious matters, Espejo wrote a theological letter, Carta al Padre la Graña sobre indulgencias (Letter to Father la Graña about indulgences). In this work, he looked at indulgences in the Catholic Church. The letter showed a profound knowledge of theology and dogma. It analyzed the historical beginnings of indulgences and their development and cited decrees and bulls written about abuses of indulgences. In this work, Espejo staunchly supported the authority of the Pope.

The Presidency of Quito was especially concerned with prevention of smallpox. Villalengua, President of the Audiencia, gathered all of Quito's Physicians to discuss the application of methods suggested by the Spanish scientist Francisco Gil, and Espejo was asked to write his Reflexiones acerca de un método para preservar a los pueblos de las viruelas." Reflexiones, completed on November 11, 1785, was divided in two parts: the first dealt with prevention of smallpox in Quito, while the second dealt with obstacles on the path to its eradication. Espejo's knowledge of inoculations and the quarantine of smallpox victims was remarkably advanced for his day.

Reflexiones was sent to Madrid, where it was added as an appendix to the second edition of the medical treatise Disertación médica (1786) by Francisco Gil, a member of the Real Academia Médica de España. Instead of recognition, Espejo acquired enemies because his work criticized the Physicians and Priests in charge of public health in the Royal Audiencia for their negligence, and he was forced to leave Quito.

It appears that Espejo was motivated more by the opportunity to attack his personal enemies in this work than to analyze the case and defend the clergy of Riobamba. Still, his talent as a Lawyer can be seen in his Representaciones (Representations), which caused him to be freed after his arrest in 1787 for his supposed authorship of El Retrato de Golilla. In these documents, he defended his loyalty to the Crown, commented on the unfairness of his captivity by mentioning the indignation that many distinguished men felt about his arrest, and clarified his writing goals. This served him as a prelude to his main subject: denying being the author of El Retrato de Golilla

There he met Antonio Nariño and Francisco Antonio Zea and began to develop his ideas on liberty. In 1789, one of his followers, Juan Pio Montufar, arrived in Bogotá, and both men got the approval of important members of the government for the creation of the Escuela de la Concordia, called later the Sociedad Patriótica de Amigos del País de Quito (Patriotic Society of Friends of the Country of Quito). The Sociedad Económica de los Amigos del País (Economic Society of Friends of the Country) was a private association established in various cities throughout Enlightenment Spain and, to a lesser degree, in some of her colonies. Espejo successfully defended himself on the charges against him, and on October 2, 1789, he was set free. On December 2 he was notified he could return to Quito.

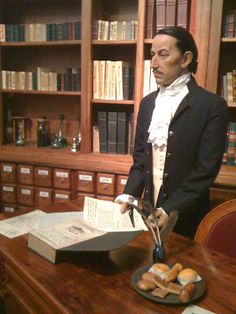

In 1790, Espejo returned to Quito to promote the "Sociedad Patriótica" (Patriotic Society), and on November 30, 1791, a branch was established in the Colegio de los Jesuitas; he was elected Director and formed four commissions. In the same year, he became Director of the first public library, the National Library, originally established with the forty thousand volumes left by the Jesuits after their expulsion from Ecuador.

On July 19, 1792, Espejo wrote another letter, Segunda carta teológica sobre la Inmaculada Concepción de María (Second theological letter about Mary's Immaculate Conception), in response to a request by the inspector of the Holy Office. This letter dealt with the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Once more, this work showed its author's deep knowledge of this religious subject and his appreciation of its standing in the 18th century. (The Immaculate Conception was not formally decreed as dogma until 1950.)

On November 11, 1793, Charles IV dissolved the society. Soon the newspaper disappeared as well. Espejo had no choice but to work as a librarian in the National Library. Because of his liberal ideas, he was imprisoned on January 30, 1795, being allowed to leave his cell only to treat his patients as a Doctor and, on December 23, to die at his home from the dysentery he acquired during his imprisonment. Eugenio Espejo died on December 28. His death certificate was registered in the book for Indians, mestizos, blacks and mulattoes.

Espejo is considered the precursor of the independence movement in Quito. He died in 1795, but his ideas had a powerful influence on three of his close friends: Juan Pío Montúfar, Juan de Dios Morales and Juan de Salinas. They, along with Manuel Rodriguez Quiroga, founded the revolutionary movement of August 10, 1809, in Quito, when the city declared independence from Spain.

Since 2000, Espejo has been depicted on the obverse of Ecuador's 10 centavo coin.

A slackening of social customs occurred on all social levels; extramarital relationships and illegitimate children were Common. Because poverty was on the rise—especially in the lower classes—many women were forced to find lodgings quickly, for Example in convents, o. This explained the abundance of the clergy in a small city like Quito; often men were ordained not because of a vocation but because it solved their economic problems and improved their community standing.