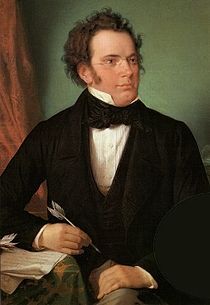

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Composer |

| Birth Day | January 17, 1931 |

| Birth Place | Alsergrund, Vienna, Austria, Austrian |

| Age | 89 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | November 19, 1828 |

| Birth Sign | Aquarius |

Net worth

Franz Peter Schubert, a renowned composer from Austria, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in 2024. Born in 1797, Schubert made significant contributions to the world of classical music, often referred to as the "Father of the Symphony" and the master of the melodious Lied. Despite his untimely death at the age of 31, Schubert's prolific output of over 600 compositions continues to inspire and captivate audiences worldwide. His unique style and emotional depth have earned him a prominent place in the history of classical music and continue to influence composers to this day.

Famous Quotes:

In love with a Countess of youthful grace,

—A pupil of Galt's; in desperate case

Young Schubert surrenders himself to another,

And fain would avoid such affectionate pother

Biography/Timeline

Schubert was born in Himmelpfortgrund (now a part of Alsergrund), Vienna, Archduchy of Austria on 31 January 1797. His father, Franz Theodor Schubert, the son of a Moravian peasant, was a parish schoolmaster; his mother, Elisabeth (Vietz), was the daughter of a Silesian master locksmith and had been a housemaid for a Viennese family before marriage. Of Franz Theodor's fourteen children (one of them illegitimate, born in 1783), nine died in infancy.

Young Schubert first came to the attention of Antonio Salieri, then Vienna's leading musical authority, in 1804, when his vocal talent was recognized. In October 1808, he became a pupil at the Stadtkonvikt (Imperial Seminary) through a choir scholarship. At the Stadtkonvikt, he was introduced to the overtures and symphonies of Mozart, and the symphonies of Joseph Haydn and his younger brother Michael. His exposure to these and other works, combined with occasional visits to the opera, laid the foundation for a broader musical education. One important musical influence came from the songs by Johann Rudolf Zumsteeg, an important Lieder Composer of the time. The precocious young student "wanted to modernize" them, as reported by Joseph von Spaun, Schubert's friend. Schubert's friendship with Spaun began at the Stadtkonvikt and lasted throughout his short life. In those early days, the financially well-off Spaun furnished the impoverished Schubert with much of his manuscript paper.

In the meantime, his genius began to show in his compositions. Schubert was occasionally permitted to lead the Stadtkonvikt's orchestra, and Salieri decided to start training him privately in music theory and even in composition. It was the first orchestra he wrote for, and he devoted much of the rest of his time at the Stadtkonvikt to composing chamber music, several songs, piano pieces and, more ambitiously, liturgical choral works in the form of a "Salve Regina" (D 27), a "Kyrie" (D 31), in addition to the unfinished "Octet for Winds" (D 72, said to commemorate the 1812 death of his mother), the cantata Wer ist groß? for male voices and orchestra (D 110, for his father's birthday in 1813), and his first symphony (D 82).

At the end of 1813, he left the Stadtkonvikt and returned home for Teacher training at the St Anna Normal-hauptschule. In 1814, he entered his father's school as Teacher of the youngest pupils. For over two years young Schubert endured such drudgery, dragging himself through it with resounding indifference. There were, however, compensatory interests even then. He continued to take private lessons in composition from Salieri, who gave Schubert more actual technical training than any of his other teachers, before they parted ways in 1817.

In 1814, Schubert met a young Soprano named Therese Grob, daughter of a local silk manufacturer, and wrote several of his liturgical works (including a "Salve Regina" and a "Tantum Ergo") for her; she was also a soloist in the premiere of his Mass No. 1 (D. 105) in September 1814. Schubert wanted to marry her, but was hindered by the harsh marriage-consent law of 1815 requiring an aspiring bridegroom to show he had the means to support a family. In November 1816, after failing to gain a musical post in Laibach (now Ljubljana, Slovenia), Schubert sent Grob's brother Heinrich a collection of songs retained by the family into the twentieth century.

One of Schubert's most prolific years was 1815. He composed over 20,000 bars of music, more than half of which was for orchestra, including nine church works (despite being agnostic), a symphony, and about 140 Lieder. In that year, he was also introduced to Anselm Hüttenbrenner and Franz von Schober, who would become his lifelong friends. Another friend, Johann Mayrhofer, was introduced to him by Spaun in 1814.

Significant changes happened in 1816. Schober, a student and of good family and some means, invited Schubert to room with him at his mother's house. The proposal was particularly opportune, for Schubert had just made the unsuccessful application for the post of kapellmeister at Laibach, and he had also decided not to resume teaching duties at his father's school. By the end of the year, he became a guest in Schober's lodgings. For a time, he attempted to increase the household resources by giving music lessons, but they were soon abandoned, and he devoted himself to composition. "I compose every morning, and when one piece is done, I begin another." During this year, he focused on orchestral and choral works, although he also continued to write Lieder (songs). Much of this work was unpublished, but manuscripts and copies circulated among friends and admirers.

In late 1817, Schubert's father gained a new position at a school in Rossau, not far from Lichtental. Schubert rejoined his father and reluctantly took up teaching duties there. In early 1818, he was rejected for membership in the prestigious Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, something that might have furthered his musical career. However, he began to gain more notice in the press, and the first public performance of a secular work, an overture performed in February 1818, received praise from the press in Vienna and abroad.

Schubert spent the summer of 1818 as a music Teacher to the family of Count Johann Karl Esterházy at their château in Zseliz (now Želiezovce, Slovakia). The pay was relatively good, and his duties teaching piano and singing to the two daughters were relatively light, allowing him to compose happily. Schubert may have written his Marche Militaire in D major (D. 733 no. 1) for Marie and Karoline, in addition to other piano duets. On his return from Zseliz, he took up residence with his friend Mayrhofer.

The compositions of 1819 and 1820 show a marked advance in development and maturity of style. The unfinished oratorio Lazarus (D. 689) was begun in February; later followed, amid a number of smaller works, by the hymn "Der 23. Psalm" (D. 706), the octet "Gesang der Geister über den Wassern" (D. 714), the Quartettsatz in C minor (D. 703), and the Wanderer Fantasy in C major for piano (D. 760). Of most notable interest is the staging in 1820 of two of Schubert's operas: Die Zwillingsbrüder (D. 647) appeared at the Theater am Kärntnertor on 14 June, and Die Zauberharfe (D. 644) appeared at the Theater an der Wien on 21 August. Hitherto, his larger compositions (apart from his masses) had been restricted to the amateur orchestra at the Gundelhof, a society which grew out of the quartet-parties at his home. Now he began to assume a more prominent position, addressing a wider public. Publishers, however, remained distant, with Anton Diabelli hesitantly agreeing to print some of his works on commission. The first seven opus numbers (all songs) appeared on these terms; then the commission ceased, and he began to receive penurious royalties. The situation improved somewhat in March 1821 when Vogl performed the song "Der Erlkönig" (D. 328) at a concert that was extremely well received. That month, Schubert composed a Variation on a Waltz by Diabelli (D 718), being one of the fifty composers who contributed to the Vaterländischer Künstlerverein publication.

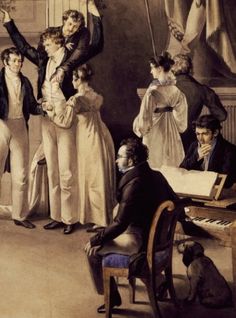

During the early 1820s, Schubert was part of a close-knit circle of artists and students who had social gatherings together that became known as Schubertiaden. The tight circle of friends with which Schubert surrounded himself was dealt a blow in early 1820. Schubert and four of his friends were arrested by the Austrian police, who (in the aftermath of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars) were on their guard against revolutionary activities and suspicious of any gathering of youth or students. One of Schubert's friends, Johann Senn, was put on trial, imprisoned for over a year, and then permanently forbidden to enter Vienna. The other four, including Schubert, were "severely reprimanded", in part for "inveighing against [officials] with insulting and opprobrious language". While Schubert never saw Senn again, he did set some of his poems, Selige Welt (D. 743) and Schwanengesang (D 744), to music. The incident may have played a role in a falling-out with Mayrhofer, with whom he was living at the time.

Despite his preoccupation with the stage, and later with his official duties, Schubert found time during these years for a significant amount of composition. He completed the Mass in A-flat major (D. 678) and, in 1822, embarked suddenly on a work which more decisively than almost any other in those years showed his maturing personal vision, the Symphony in B minor Unfinished (D. 759). The reason he left it unfinished—after two movements and sketches some way into a third—remains an enigma, and it is also remarkable that he did not mention it to any of his friends, even though, as Brian Newbould notes, he must have felt thrilled by what he was achieving. The event has been debated endlessly without resolution.

In 1823 Schubert, in addition to Fierrabras, also wrote his first large-scale song cycle, Die schöne Müllerin (D. 795), setting poems by Wilhelm Müller. This series, together with the later cycle Winterreise (D. 911, also setting texts of Müller in 1827) is widely considered one of the pinnacles of Lieder. He also composed the song Du bist die Ruh' (You are rest and peace, D. 776) during this year. Also in that year, symptoms of syphilis first appeared.

In 1824, he wrote the Variations in E minor for flute and piano Trockne Blumen, a song from the cycle Die schöne Müllerin, and several string quartets. He also wrote the Sonata in A minor for arpeggione and piano (D. 821) at the time when there was a minor craze over that instrument. In the spring of that year, he wrote the Octet in F major (D. 803), a Sketch for a 'Grand Symphony'; and in the summer went back to Zseliz. There he became attracted to Hungarian musical idiom, and wrote the Divertissement à la hongroise in G minor for piano duet (D. 818) and the String Quartet in A minor Rosamunde (D. 804). It has been said that he held a hopeless passion for his pupil, the Countess Karoline Esterházy, but the only work he dedicated to her was his Fantasia in F minor for piano duet (D. 940). His friend Eduard von Bauernfeld penned the following verse, which appears to reference Schubert's unrequited sentiments:

The setbacks of previous years were compensated by the prosperity and happiness of 1825. Publication had been moving more rapidly, the stress of poverty was for a time lightened, and in the summer he had a pleasant holiday in Upper Austria where he was welcomed with enthusiasm. It was during this tour that he produced the seven-song cycle Fräulein am See, based on Walter Scott's Lady of the Lake, and including "Ellens Gesang III" ("Hymn to the Virgin") (D. 839, Op. 52, No. 6); the lyrics of Adam Storck's German translation of the Scott poem are now frequently substituted by the full text of the traditional Roman Catholic prayer Hail Mary (Ave Maria in Latin)—for which the Schubert melody is not an original setting, as it is widely, though mistakenly, thought. The original only opens with the greeting "Ave Maria", which also recurs only in the refrain. In 1825, Schubert also wrote the Piano Sonata in A minor (D 845, first published as op. 42), and began the Symphony in C major (Great C major, D. 944), which was completed the following year.

From 1826 to 1828, Schubert resided continuously in Vienna, except for a brief visit to Graz in 1827. The history of his life during these three years was comparatively uninteresting, and is little more than a record of his compositions. In 1826, he dedicated a symphony (D. 944, that later came to be known as the Great C major) to the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde and received an honorarium in return. In the spring of 1828, he gave, for the only time in his career, a public concert of his own works, which was very well received. The compositions themselves are a sufficient biography. The String Quartet No. 14 in D minor (D. 810), with the variations on Death and the Maiden, was written during the winter of 1825–1826, and first played on 25 January 1826. Later in the year came the String Quartet No. 15 in G major, (D 887, first published as op. 161), the Rondo in B minor for violin and piano (D. 895), Rondeau brillant, and the Piano Sonata in G major, (D 894, first published as Fantasie in G, op. 78). To these should be added the three Shakespearian songs, of which "Ständchen" (D. 889) and "An Sylvia" (D. 891) were allegedly written on the same day, the former at a tavern where he broke his afternoon's walk, the latter on his return to his lodging in the evening.

In 1827, Schubert wrote the song cycle Winterreise (D. 911), a colossal peak in art song ("remarkable" was the way it was described at the Schubertiades), the Fantasy in C major for violin and piano (D. 934, first published as op. post. 159), the Impromptus for piano, and the two piano trios (the first in B-flat major (D. 898), and the second in E-flat major, (D. 929); in 1828 the cantata Mirjams Siegesgesang (Victory Song of Miriam, D 942) on a text by Franz Grillparzer, the Mass in E-flat major (D. 950), the Tantum Ergo (D. 962) in the same key, the String Quintet in C major (D. 956), the second "Benedictus" to the Mass in C major (D. 452), the three final piano sonatas (D. 958, D. 959, and D. 960), and the song cycle 13 Lieder nach Gedichten von Rellstab und Heine for voice and piano, also known as Schwanengesang (Swan-song, D. 957). This collection, while not a true song cycle, retains a unity amongst the individual songs, touching depths of tragedy and of the morbidly supernatural, which had rarely been plumbed by any Composer in the century preceding it. Six of these are set to words by Heinrich Heine, whose Buch der Lieder appeared in the autumn. The Symphony in C major (D. 944) is dated 1828, but Schubert scholars believe that this symphony was largely written in 1825–1826 (being referred to while he was on holiday at Gastein in 1825—that work, once considered lost, is now generally seen as an early stage of his C major symphony) and was revised for prospective performance in 1828. This was a fairly unusual practice for Schubert, for whom publication, let alone performance, was rarely contemplated for most of his larger-scale works during his lifetime. The huge, Beethovenian work was declared "unplayable" by a Viennese orchestra. In the last weeks of his life, he began to Sketch three movements for a new Symphony in D major (D 936A).

Among Schubert's treatments of the poetry of Goethe, his settings of "Gretchen am Spinnrade" (D. 118) and "Der Erlkönig" (D. 328) are particularly striking for their dramatic content, forward-looking uses of harmony, and their use of eloquent pictorial keyboard figurations, such as the depiction of the spinning wheel and treadle in the piano in "Gretchen" and the furious and ceaseless gallop in "Erlkönig". He composed music using the poems of a myriad of poets, with Goethe, Mayrhofer and Schiller being the top three most frequent, and others like Heinrich Heine, Friedrich Rückert and Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff among many others. Also of particular note are his two song cycles on the poems of Wilhelm Müller, Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise, which helped to establish the genre and its potential for musical, poetic, and almost operatic dramatic narrative. His last song cycle published in 1828 after his death, Schwanengesang, is also an innovative contribution to German lieder literature, as it features poems by different poets, namely Ludwig Rellstab, Heine, and Johann Gabriel Seidl. The Wiener Theaterzeitung, writing about Winterreise at the time, commented that it was a work that "none can sing or hear without being deeply moved".

From the 1830s through the 1870s, Franz Liszt transcribed and arranged a number of Schubert's works, particularly the songs. Liszt, who was a significant force in spreading Schubert's work after his death, said Schubert was "the most poetic musician who ever lived." Schubert's symphonies were of particular interest to Antonín Dvořák, with Hector Berlioz and Anton Bruckner acknowledging the influence of the Great C major Symphony. It was Robert Schumann who, having seen the manuscript of the 'Great' C Major Symphony in Vienna in 1838, drew it to the attention of Mendelssohn, who gave the first performance of it in Leipzig in 1839. In the 20th century, composers such as Anton Webern, Benjamin Britten, Richard Strauss, George Crumb and Hans Zender either championed or paid homage to Schubert in their work. Britten, an accomplished Pianist, accompanied many of Schubert's Lieder and performed many piano solo and duet works.

When Schubert died he had around 100 opus numbers published, mainly songs, chamber music and smaller piano compositions. Publication of smaller pieces continued (including opus numbers up to 173 in 1860s, 50 instalments with songs published by Diabelli and dozens of first publications Peters), but the manuscripts of many of the longer works, whose existence was not widely known, remained hidden in cabinets and file boxes of Schubert's family, friends, and publishers. Even some of Schubert's friends were unaware of the full scope of what he wrote, and for many years he was primarily recognized as the "prince of song", although there was recognition of some of his larger-scale efforts. In 1838 Robert Schumann, on a visit to Vienna, found the dusty manuscript of the C major Symphony (D. 944) and took it back to Leipzig where it was performed by Felix Mendelssohn and celebrated in the Neue Zeitschrift. An important step towards the recovery of the neglected works was the journey to Vienna which Sir George Grove (widely known for the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians) and Arthur Sullivan made in the autumn of 1867. The travellers rescued from oblivion seven symphonies, the Rosamunde incidental music, some of the masses and operas, several chamber works, and a vast quantity of Miscellaneous pieces and songs. This led to more widespread public interest in Schubert's work.

In 1872, a memorial to Franz Schubert was erected in Vienna's Stadtpark. In 1888, both Schubert's and Beethoven's graves were moved to the Zentralfriedhof where they can now be found next to those of Johann Strauss II and Johannes Brahms. The cemetery in Währing was converted into a park in 1925, called the Schubert Park, and his former grave site was marked by a bust. His epitaph reads, Die Tonkunst begrub hier einen reichen Besitz, aber noch viel schönere Hoffnungen (“The art of music has here interred a precious treasure, but yet far fairer hopes”).

Since relatively few of Schubert's works were published in his lifetime, only a small number of them have opus numbers assigned, and even in those cases, the sequence of the numbers does not give a good indication of the order of composition. Austrian musicologist Otto Erich Deutsch (1883–1967) is known for compiling the first comprehensive catalogue of Schubert's works. This was first published in English in 1951 (Schubert Thematic Catalogue) and subsequently revised for a new edition in German in 1978 (Franz Schubert: Thematisches Verzeichnis seiner Werke in chronologischer Folge – Franz Schubert: Thematic Catalogue of his Works in Chronological Order).

From 1884 to 1897, Breitkopf & Härtel published Franz Schubert's Works, a critical edition including a contribution made – among others – by Johannes Brahms, Editor of the first series containing eight symphonies. The publication of the Neue Schubert-Ausgabe by Bärenreiter started in the second half of the 20th century.

Antonín Dvořák wrote in 1894 that Schubert, whom he considered one of the truly great composers, was clearly influential on shorter works, especially Lieder and shorter piano works: "The tendency of the romantic school has been toward short forms, and although Weber helped to show the way, to Schubert belongs the chief credit of originating the short Models of piano forte pieces which the romantic school has preferably cultivated. [...] Schubert created a new epoch with the Lied. [...] All other songwriters have followed in his footsteps."

In 1897, the 100th anniversary of Schubert's birth was marked in the musical world by festivals and performances dedicated to his music. In Vienna, there were ten days of concerts, and the Emperor Franz Joseph gave a speech recognizing Schubert as the creator of the art song, and one of Austria's favorite sons. Karlsruhe saw the first production of his opera Fierabras.

In 1928, Schubert week was held in Europe and the United States to mark the centenary of the composer's death. Works by Schubert were performed in churches, in concert halls, and on radio stations. A competition, with top prize money of $10,000 and sponsorship by the Columbia Phonograph Company, was held for "original symphonic works presented as an apotheosis of the lyrical genius of Schubert, and dedicated to his memory". The winning entry was Kurt Atterberg's sixth symphony.

Schubert has featured as a character in a number of films including Schubert's Dream of Spring (1931), Gently My Songs Entreat (1933), Serenade (1940), The Great Awakening (1941), It's Only Love (1947), Franz Schubert (1953), Das Dreimäderlhaus (1958), and Notturno (1986).

In July 1947 the Austrian Composer Ernst Krenek discussed Schubert's style, abashedly admitting that he had at first "shared the wide-spread opinion that Schubert was a lucky Inventor of pleasing tunes ... lacking the dramatic power and searching intelligence which distinguished such 'real' masters as J.S. Bach or Beethoven". Krenek wrote that he reached a completely different assessment after close study of Schubert's pieces at the urging of friend and fellow Composer Eduard Erdmann. Krenek pointed to the piano sonatas as giving "ample evidence that [Schubert] was much more than an easy-going tune-smith who did not know, and did not care, about the craft of composition." Each sonata then in print, according to Krenek, exhibited "a great wealth of technical finesse" and revealed Schubert as "far from satisfied with pouring his charming ideas into conventional molds; on the contrary he was a thinking Artist with a keen appetite for experimentation."

In 1977, the German electronic band Kraftwerk recorded an instrumental tribute song called "Franz Schubert" on their album Trans-Europe Express.

Schubert's chamber music continues to be popular. In a poll, the results of which were announced in October 2008, the ABC in Australia found that Schubert's chamber works dominated the field, with the Trout Quintet coming first, followed by two of his other works.

The works of his last two years reveal a Composer increasingly meditating on the darker side of the human psyche and human relationships, and with a deeper sense of spiritual awareness and conception of the 'beyond'. He reaches extraordinary depths in several chillingly dark songs of this period, especially in the larger cycles. For Example, the song "Der Doppelgänger" (D 957, No. 13, "The double") reaching an extraordinary climax, conveying madness at the realization of rejection and imminent death – a stark and visionary picture in sound and words that had been prefigured a year before by "Der Leiermann" (D 911, No. 24, "The Hurdy-Gurdy Man") at the end of Winterreise – and yet the Composer is able to touch repose and communion with the infinite in the almost timeless ebb and flow of the string quintet and his last three piano sonatas, moving between joyful, vibrant poetry and remote introspection. Even in large-scale works he was sometimes using increasingly sparse textures; Newbould cites his writing in the fragmentary Symphony in D major (D 936A), probably the work of his very last two months. In this work, he anticipates Mahler's use of folksong-like harmonics and bare soundscapes. Schubert expressed the wish, were he to survive his final illness, to further develop his knowledge of harmony and counterpoint, and had actually made appointments for lessons with the counterpoint master Simon Sechter.

Appreciation of Schubert's music while he was alive was limited to a relatively small circle of admirers in Vienna, but interest in his work increased significantly in the decades following his death. Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt, Johannes Brahms and other 19th-century composers discovered and championed his works. Today, Schubert is ranked among the greatest composers of the late Classical and early Romantic eras and is one of the most frequently performed composers of the early 19th century.