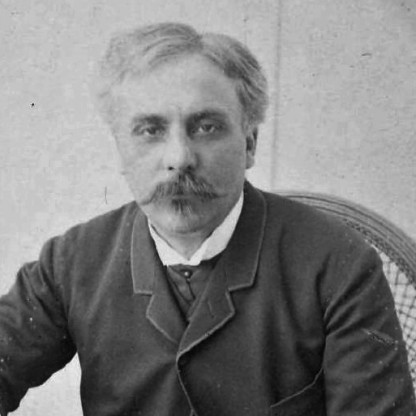

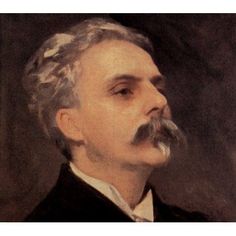

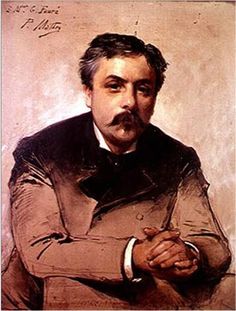

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | French Composer & Pianist |

| Birth Day | May 18, 2012 |

| Birth Place | Pamiers, Ariège, Midi-Pyrénées, France, French |

| Age | 8 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | November 4, 1924 |

| Birth Sign | Gemini |

Net worth: $1.7 Million (2024)

Gabriel Fauré, a renowned French composer and pianist, is expected to have a net worth of $1.7 million by 2024. Fauré's immense talent in music has contributed to his impressive financial standing. As a composer, he has created a rich catalogue of compositions, including operas, chamber music, and piano works. His contributions to the French music scene have earned him great recognition and admiration. Fauré's net worth is a testament to his successful career and his significant impact on the world of music.

Famous Quotes:

I grew up, a rather quiet well-behaved child, in an area of great beauty. ... But the only thing I remember really clearly is the harmonium in that little chapel. Every time I could get away I ran there – and I regaled myself. ... I played atrociously ... no method at all, quite without technique, but I do remember that I was happy; and if that is what it means to have a vocation, then it is a very pleasant thing.

Biography/Timeline

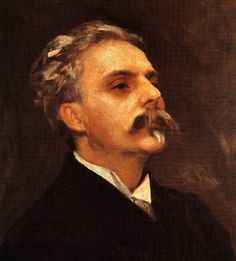

Fauré was born in Pamiers, Ariège, Midi-Pyrénées, in the south of France, the fifth son and youngest of six children of Toussaint-Honoré Fauré (1810–85) and Marie-Antoinette-Hélène Lalène-Laprade (1809–87). According to the biographer Jean-Michel Nectoux, the Fauré family dates to the 13th century in that part of France. The family had at one time been substantial landowners, but by the 19th century its means were reduced. The composer's paternal grandfather, Gabriel, was a butcher whose son became a schoolmaster. In 1829 Fauré's parents married. His mother was the daughter of a minor member of the nobility. He was the only one of the six children to display musical talent; his four brothers pursued careers in journalism, politics, the army and the civil Service, and his sister had a traditional life as the wife of a public servant.

The young Fauré was sent to live with a foster mother until he was four years old. When his father was appointed Director of the École Normale d'Instituteurs, a Teacher training college, at Montgauzy, near Foix, in 1849, Fauré returned to live with his family. There was a chapel attached to the school, which Fauré recalled in the last year of his life:

An old blind woman, who came to Listen and give the boy advice, told his father of Fauré's gift for music. In 1853 Simon-Lucien Dufaur de Saubiac, of the National Assembly, heard Fauré play and advised Toussaint-Honoré to send him to the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse (School of Classical and Religious Music, better known as the École Niedermeyer de Paris, which Louis Niedermeyer was setting up in Paris. After reflecting for a year, Fauré's father agreed and took the nine-year-old boy to Paris in October 1854.

In Copland's view, the early songs, written in the 1860s and 1870s under the influence of Gounod, except for isolated songs such as "Après un rêve" or "Au bord de l'eau", show little sign of the Artist to come. With the second volume of the sixty collected songs written during the next two decades, Copland judged, came the first mature examples of "the real Fauré". He instanced "Les berceaux", "Les roses d'Ispahan" and especially "Clair de lune" as "so beautiful, so perfect, that they have even penetrated to America", and drew attention to less well known mélodies such as "Le secret", "Nocturne", and "Les présents". Fauré also composed a number of song cycles. Cinq mélodies "de Venise", Op. 58 (1891), was described by Fauré as a novel kind of song suite, in its use of musical themes recurring over the cycle. For the later cycle La bonne chanson, Op. 61 (1894), there were five such themes, according to Fauré. He also wrote that La bonne chanson was his most spontaneous composition, with Emma Bardac singing back to him each day's newly written material.

When Niedermeyer died in March 1861, Camille Saint-Saëns took charge of piano studies and introduced contemporary music, including that of Schumann, Liszt and Wagner. Fauré recalled in old age, "After allowing the lessons to run over, he would go to the piano and reveal to us those works of the masters from which the rigorous classical nature of our programme of study kept us at a distance and who, moreover, in those far-off years, were scarcely known. ... At the time I was 15 or 16, and from this time dates the almost filial attachment ... the immense admiration, the unceasing gratitude I [have] had for him, throughout my life."

Saint-Saëns took great pleasure in his pupil's progress, which he helped whenever he could; Nectoux comments that at each step in Fauré's career "Saint-Saëns's Shadow can effectively be taken for granted." The close friendship between them lasted until Saint-Saëns died sixty years later. Fauré won many prizes while at the school, including a premier prix in composition for the Cantique de Jean Racine, Op. 11, the earliest of his choral works to enter the regular repertory. He left the school in July 1865, as a Laureat in organ, piano, harmony and composition, with a Maître de Chapelle diploma.

On leaving the École Niedermeyer, Fauré was appointed organist at the Church of Saint-Sauveur, at Rennes in Brittany. He took up the post in January 1866. During his four years at Rennes he supplemented his income by taking private pupils, giving "countless piano lessons". At Saint-Saëns's regular prompting he continued to compose, but none of his works from this period survive. He was bored at Rennes and had an uneasy relationship with the parish priest, who correctly doubted Fauré's religious conviction. Fauré was regularly seen stealing out during the sermon for a cigarette, and in early 1870, when he turned up to play at Mass one Sunday still in his evening clothes, having been out all night at a ball, he was asked to resign. Almost immediately, with the discreet aid of Saint-Saëns, he secured the post of assistant organist at the church of Notre-Dame de Clignancourt, in the north of Paris. He remained there for only a few months. On the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 he volunteered for military Service. He took part in the action to raise the Siege of Paris, and saw action at Le Bourget, Champigny and Créteil. He was awarded a Croix de Guerre.

Fauré was a founding member of the Société Nationale de Musique, formed in February 1871 under the joint chairmanship of Romain Bussine and Saint-Saëns, to promote new French music. Other members included Georges Bizet, Emmanuel Chabrier, Vincent d'Indy, Henri Duparc, César Franck, Édouard Lalo and Jules Massenet. Fauré became secretary of the society in 1874. Many of his works were first presented at the society's concerts.

In 1874 Fauré moved from Saint-Sulpice to the Église de la Madeleine, acting as deputy for the principal organist, Saint-Saëns, during the latter's many absences on tour. Some admirers of Fauré's music have expressed regret that although he played the organ professionally for four decades, he left no solo compositions for the instrument. He was renowned for his improvisations, and Saint-Saëns said of him that he was "a first class organist when he wanted to be". Fauré preferred the piano to the organ, which he played only because it gave him a regular income. Duchen speculates that he positively disliked the organ, possibly because "for a Composer of such delicacy of nuance, and such sensuality, the organ was simply not subtle enough."

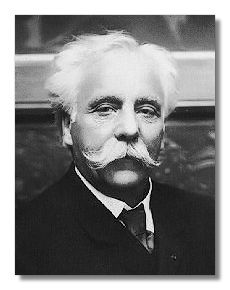

Fauré suffered from poor health in his later years, brought on in part by heavy smoking. Despite this, he remained available to young composers, including members of Les Six, most of whom were devoted to him. Nectoux writes, "In old age he attained a kind of serenity, without losing any of his remarkable spiritual vitality, but rather removed from the sensualism and the passion of the works he wrote between 1875 and 1895."

The year 1877 was significant for Fauré, both professionally and personally. In January his first violin sonata was performed at a Société Nationale concert with great success, marking a turning-point in his composing career at the age of 31. Nectoux counts the work as the composer's first great masterpiece. In March, Saint-Saëns retired from the Madeleine, succeeded as organist by Théodore Dubois, his choirmaster; Fauré was appointed to take over from Dubois. In July Fauré became engaged to Pauline Viardot's daughter Marianne, with whom he was deeply in love. To his great sorrow, she broke off the engagement in November 1877, for reasons that are not clear. To distract Fauré, Saint-Saëns took him to Weimar and introduced him to Franz Liszt. This visit gave Fauré a liking for foreign travel, which he indulged for the rest of his life. From 1878, he and Messager made trips abroad to see Wagner operas. They saw Das Rheingold and Die Walküre at the Cologne Opera; the complete Ring cycle at the Hofoper in Munich and at Her Majesty's Theatre in London; and Die Meistersinger in Munich and at Bayreuth, where they also saw Parsifal. They frequently performed as a party piece their joint composition, the irreverent Souvenirs de Bayreuth. This short, up-tempo piano work for four hands sends up themes from The Ring. Fauré admired Wagner and had a detailed knowledge of his music, but he was one of the few composers of his generation not to come under Wagner's musical influence.

In 1883 Fauré married Marie Fremiet, the daughter of a leading Sculptor, Emmanuel Fremiet. The marriage was affectionate, but Marie became resentful of Fauré's frequent absences, his dislike of domestic life – "horreur du domicile" – and his love affairs, while she remained at home. Though Fauré valued Marie as a friend and confidante, writing to her often – sometimes daily – when away from home, she did not share his passionate nature, which found fulfilment elsewhere. Fauré and his wife had two sons. The first, born in 1883, Emmanuel Fauré-Fremiet (Marie insisted on combining her family name with Fauré's), became a Biologist of international reputation. The second son, Philippe, born in 1889, became a writer; his works included histories, plays, and biographies of his father and grandfather.

To support his family, Fauré spent most of his time in running the daily services at the Madeleine and giving piano and harmony lessons. His compositions earned him a negligible amount, because his publisher bought them outright, paying him an average of 60 francs for a song, and Fauré received no royalties. During this period, he wrote several large-scale works, in addition to many piano pieces and songs, but he destroyed most of them after a few performances, only retaining a few movements in order to re-use motifs. Among the works surviving from this period is the Requiem, begun in 1887 and revised and expanded, over the years, until its final version dating from 1901. After its first performance, in 1888, the priest in charge told the Composer, "We don't need these novelties: the Madeleine's repertoire is quite rich enough."

The Requiem, Op. 48, was not composed to the memory of a specific person but, in Fauré's words, "for the pleasure of it." It was first performed in 1888. It has been described as "a lullaby of death" because of its predominantly gentle tone. Fauré omitted the Dies irae, though reference to the day of judgment appears in the Libera me, which, like Verdi, he added to the normal liturgical text. Fauré revised the Requiem over the years, and a number of different performing versions are now in use, from the earliest, for small forces, to the final revision with full orchestra.

During the 1890s Fauré's fortunes improved. When Ernest Guiraud, professor of composition at the Paris Conservatoire, died in 1892, Saint-Saëns encouraged Fauré to apply for the vacant post. The faculty of the Conservatoire regarded Fauré as dangerously modern, and its head, Ambroise Thomas, blocked the appointment, declaring, "Fauré? Never! If he's appointed, I resign." However, Fauré was appointed to another of Guiraud's posts, inspector of the music conservatories in the French provinces. He disliked the prolonged travelling around the country that the work entailed, but the post gave him a steady income and enabled him to give up teaching amateur pupils.

Contemporary accounts agree that Fauré was extremely attractive to women; in Duchen's phrase, "his conquests were legion in the Paris salons." After a romantic attachment to the singer Emma Bardac from around 1892, followed by another to the Composer Adela Maddison, in 1900 Fauré met the Pianist Marguerite Hasselmans, the daughter of Alphonse Hasselmans. This led to a relationship which lasted for the rest of Fauré's life. He maintained her in a Paris apartment, and she acted openly as his companion.

About this time, or shortly afterwards, Fauré's liaison with Emma Bardac began; in Duchen's words, "for the first time, in his late forties, he experienced a fulfilling, passionate relationship which extended over several years". His principal biographers all agree that this affair inspired a burst of creativity and a new originality in his music, exemplified in the song cycle La bonne chanson. Fauré wrote the Dolly Suite for piano duet between 1894 and 1897 and dedicated it to Bardac's daughter Hélène, known as "Dolly". Some people suspected that Fauré was Dolly's father, but biographers including Nectoux and Duchen think it unlikely. Fauré's affair with Emma Bardac is thought to have begun after Dolly was born, though there is no conclusive evidence either way.

In 1896 Ambroise Thomas died, and Théodore Dubois took over as head of the Conservatoire. Fauré succeeded Dubois as chief organist of the Madeleine. Dubois' move had further repercussions: Massenet, professor of composition at the Conservatoire, had expected to succeed Thomas, but had overplayed his hand by insisting on being appointed for life. He was turned down, and when Dubois was appointed instead, Massenet resigned his professorship in fury. Fauré was appointed in his place. He taught many young composers, including Maurice Ravel, Florent Schmitt, Charles Koechlin, Louis Aubert, Jean Roger-Ducasse, George Enescu, Paul Ladmirault, Alfredo Casella and Nadia Boulanger. In Fauré's view, his students needed a firm grounding in the basic skills, which he was happy to delegate to his capable assistant André Gedalge. His own part came in helping them make use of these skills in the way that suited each student's talents. Roger-Ducasse later wrote, "Taking up whatever the pupils were working on, he would evoke the rules of the form at hand ... and refer to examples, always drawn from the masters." Ravel always remembered Fauré's open-mindedness as a Teacher. Having received Ravel's String Quartet with less than his usual enthusiasm, Fauré asked to see the manuscript again a few days later, saying, "I could have been wrong". The musicologist Henry Prunières wrote, "What Fauré developed among his pupils was taste, harmonic sensibility, the love of pure lines, of unexpected and colorful modulations; but he never gave them [recipes] for composing according to his style and that is why they all sought and found their own paths in many different, and often opposed, directions."

Fauré's works of the last years of the century include incidental music for the English premiere of Maurice Maeterlinck's Pelléas et Mélisande (1898) and Prométhée, a lyric tragedy composed for the amphitheatre at Béziers. Written for outdoor performance, the work is scored for huge instrumental and vocal forces. Its premiere in August 1900 was a great success, and it was revived at Béziers the following year and in Paris in 1907. A version with orchestration for normal opera house-sized forces was given at the Paris Opéra in May 1917 and received more than forty performances in Paris thereafter.

From 1903 to 1921, Fauré regularly wrote music criticism for Le Figaro, a role in which he was not at ease. Nectoux writes that Fauré's natural kindness and broad-mindedness predisposed him to emphasise the positive aspects of a work.

Fauré made piano rolls of his music for several companies between 1905 and 1913. Well over a hundred recordings of Fauré's music were made between 1898 and 1905, mostly of songs, with a few short chamber works, by performers including the Singers Jean Noté and Pol Plançon and players such as Jacques Thibaud and Alfred Cortot. By the 1920s a range of Fauré's more popular songs were on record, including "Après un rêve" sung by Olga Haley, and "Automne" and "Clair de lune" sung by Ninon Vallin. In the 1930s better-known performers recorded Fauré pieces, including Georges Thill ("En prière"), and Jacques Thibaud and Alfred Cortot (Violin Sonata No. 1 and Berceuse). The Sicilienne from Pelléas et Mélisande was recorded in 1938.

The turn of the 20th century saw a rise in the popularity of Fauré's music in Britain, and to a lesser extent in Germany, Spain and Russia. He visited England frequently, and an invitation to play at Buckingham Palace in 1908 opened many other doors in London and beyond. He attended the London premiere of Elgar's First Symphony, in 1908, and dined with the Composer afterwards. Elgar later wrote to their mutual friend Frank Schuster that Fauré "was such a real gentleman – the highest kind of Frenchman and I admired him greatly." Elgar tried to get Fauré's Requiem put on at the Three Choirs Festival, but it did not finally have its English premiere until 1937, nearly fifty years after its first performance in France. Composers from other countries also loved and admired Fauré. In the 1880s Tchaikovsky had thought him "adorable"; Albéniz and Fauré were friends and correspondents until the former's early death in 1909; Richard Strauss sought his advice; and in Fauré's last years, the young American Aaron Copland was a devoted admirer.

Fauré was elected to the Institut de France in 1909, after his father-in-law and Saint-Saëns, both long-established members, had canvassed strongly on his behalf. He won the ballot by a narrow margin, with 18 votes against 16 for the other candidate, Widor. In the same year a group of young composers led by Ravel and Koechlin broke with the Société Nationale de Musique, which under the presidency of Vincent d'Indy had become a reactionary organisation, and formed a new group, the Société musicale indépendante. While Fauré accepted the presidency of this society, he also remained a member of the older one and continued on the best of terms with d'Indy; his sole concern was the fostering of new music. In 1911 he oversaw the Conservatoire's move to new premises in the rue de Madrid.

Fauré was not greatly interested in orchestration, and on occasion asked his former students such as Jean Roger-Ducasse and Charles Koechlin to orchestrate his concert and theatre works. In Nectoux's words, Fauré's generally sober orchestral style reflects "a definite aesthetic attitude ... The idea of timbre was not a determining one in Fauré's musical thinking". He was not attracted by flamboyant combinations of tone-colours, which he thought either self-indulgent or a disguise for lack of real musical invention. He told his students that it should be possible to produce an orchestration without resorting to glockenspiels, celestas, xylophones, bells or electrical instruments. Debussy admired the spareness of Fauré's orchestration, finding in it the transparency he strove for in his own 1913 ballet Jeux; Poulenc, by contrast, described Fauré's orchestration as "a leaden overcoat ... instrumental mud". Fauré's best-known orchestral works are the suites Masques et bergamasques (based on music for a dramatic entertainment, or divertissement comique), which he orchestrated himself, Dolly, orchestrated by Henri Rabaud, and Pelléas et Mélisande which draws on incidental music for Maeterlinck's play; the stage version was orchestrated by Koechlin, but Fauré himself reworked the orchestration for the published suite.

In 1920, at the age of 75, Fauré retired from the Conservatoire because of his increasing deafness and frailty. In that year he received the Grand-Croix of the Légion d'honneur, an honour rare for a musician. In 1922 the President of the republic, Alex Andre Millerand, led a public tribute to Fauré, a national hommage, described in The Musical Times as "a splendid celebration at the Sorbonne, in which the most illustrious French artists participated, [which] brought him great joy. It was a poignant spectacle, indeed: that of a man present at a concert of his own works and able to hear not a single note. He sat gazing before him pensively, and, in spite of everything, grateful and content."

Fauré is regarded as one of the masters of the French art song, or mélodie. Ravel wrote in 1922 that Fauré had saved French music from the dominance of the German Lied. Two years later the critic Samuel Langford wrote of Fauré, "More surely almost than any Writer in the world he commanded the faculty to create a song all of a piece, and with a sustained intensity of mood which made it like a single thought". In a 2011 article the Pianist and Writer Roy Howat and the musicologist Emily Kilpatrick wrote:

In the chamber repertoire, his two piano quartets, in C minor and G minor, particularly the former, are among Fauré's better-known works. His other chamber music includes two piano quintets, two cello sonatas, two violin sonatas, a piano trio and a string quartet. Copland (writing in 1924 before the string quartet was finished) held the second quintet to be Fauré's masterpiece: "... a pure well of spirituality ... extremely classic, as far removed as possible from the romantic temperament." Other critics have taken a less favourable view: The Record Guide commented, "The ceaseless flow and restricted colour scheme of Fauré's last manner, as exemplified in this Quintet, need very careful management, if they are not to become tedious." Fauré's last work, the String Quartet, has been described by critics in Gramophone magazine as an intimate meditation on the last things, and "an extraordinary work by any standards, ethereal and other-worldly with themes that seem constantly to be drawn skywards."

By the 1940s there were a few more Fauré works in the catalogues. A survey by John Culshaw in December 1945 singled out recordings of piano works played by Kathleen Long (including the Nocturne No. 6, Barcarolle No. 2, the Thème et Variations, Op. 73, and the Ballade Op. 19 in its orchestral version conducted by Boyd Neel), the Requiem conducted by Ernest Bourmauck, and seven songs sung by Maggie Teyte. Fauré's music began to appear more frequently in the record companies' releases in the 1950s. The Record Guide, 1955, listed the Piano Quartet No. 1, Piano Quintet No. 2, the String Quartet, both Violin Sonatas, the Cello Sonata No. 2, two new recordings of the Requiem, and the complete song cycles La bonne chanson and La chanson d'Ève.

In a centenary tribute in 1945, the musicologist Leslie Orrey wrote in The Musical Times, "'More profound than Saint-Saëns, more varied than Lalo, more spontaneous than d'Indy, more classic than Debussy, Gabriel Fauré is the master par excellence of French music, the perfect mirror of our musical genius.' Perhaps, when English Musicians get to know his work better, these words of Roger-Ducasse will seem, not over-praise, but no more than his due."

Influences on Fauré, particularly in his early work, included not only Chopin but Mozart and Schumann. The authors of The Record Guide (1955), Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, wrote that Fauré learnt restraint and beauty of surface from Mozart, tonal freedom and long melodic lines from Chopin, "and from Schumann, the sudden felicities in which his development sections abound, and those codas in which whole movements are briefly but magically illuminated." His work was based on the strong understanding of harmonic structures that he gained at the École Niedermeyer from Niedermeyer's successor Gustave Lefèvre. Lefèvre wrote the book Traité d'harmonie (Paris, 1889), in which he sets out a harmonic theory that differs significantly from the classical theory of Rameau, no longer outlawing certain chords as "dissonant". By using unresolved mild discords and colouristic effects, Fauré anticipated the techniques of Impressionist composers.

In the LP and particularly the CD era, the record companies have built up a substantial catalogue of Fauré's music, performed by French and non-French Musicians. Several modern recordings of Fauré's music have come to public notice as prize-winners in annual awards organised by Gramophone and the BBC. Sets of his major orchestral works have been recorded under conductors including Michel Plasson (1981) and Yan Pascal Tortelier (1996). Fauré's main chamber works have all been recorded, with players including the Ysaÿe Quartet, Domus, Paul Tortelier, Arthur Grumiaux, and Joshua Bell. The complete piano works have been recorded by Kathryn Stott (1995), and Paul Crossley (1984–85), with substantial sets of the major piano works from Jean-Philippe Collard (1982–84), Pascal Rogé (1990), and Kun-Woo Paik (2002). Fauré's songs have all been recorded for CD, including a complete set (2005), anchored by the accompanist Graham Johnson, with soloists Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, Felicity Lott, John Mark Ainsley and Jennifer Smith, among others. The Requiem and the shorter choral works are also well represented on disc. Pénélope has been recorded twice, with casts headed by Régine Crespin in 1956, and Jessye Norman in 1981, conducted respectively by Désiré-Émile Inghelbrecht and Charles Dutoit. Prométhée has not been recorded in full, but extensive excerpts were recorded under Roger Norrington (1980).

A 2001 article on Fauré in Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians concludes thus:

Aaron Copland wrote that although Fauré's works can be divided into the usual "early", "middle" and "late" periods, there is no such radical difference between his first and last manners as is evident with many other composers. Copland found premonitions of late Fauré in even the earliest works, and traces of the early Fauré in the works of his old age: "The themes, harmonies, form, have remained essentially the same, but with each new work they have all become more fresh, more personal, more profound." When Fauré was born, Berlioz and Chopin were still composing; the latter was among Fauré’s early influences. In his later years Fauré developed compositional techniques that foreshadowed the atonal music of Schoenberg, and, later still, drew discreetly on the techniques of jazz. Duchen writes that early works such as the Cantique de Jean Racine are in the tradition of French nineteenth-century Romanticism, yet his late works are as modern as any of the works of his pupils.