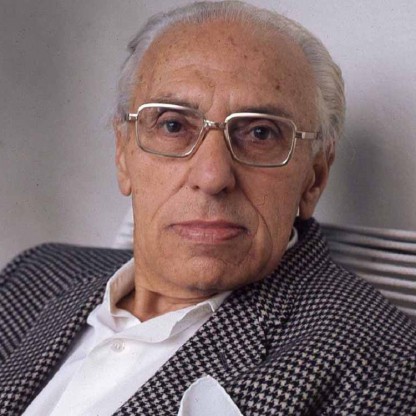

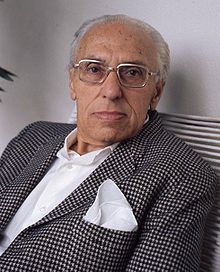

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Film Director |

| Birth Day | July 07, 1899 |

| Birth Place | Manhattan, New York, U.S., United States |

| Age | 120 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | January 24, 1983(1983-01-24) (aged 83)\nLos Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Leo |

| Cause of death | Heart failure |

| Occupation | Film director |

| Years active | 1930–81 |

Net worth: $950,000 (2024)

George Cukor, the renowned film director from the United States, is estimated to have a net worth of $950,000 in 2024. Known for his exceptional talent in the film industry, Cukor has carved a special place for himself with his outstanding directorial skills. Having directed numerous critically acclaimed films, Cukor has not only received widespread recognition but has also accumulated a considerable amount of wealth throughout his career. With his remarkable contributions to cinema, George Cukor's net worth stands as a testament to his success and influence in the world of filmmaking.

Biography/Timeline

Following his graduation in 1917, Cukor was expected to follow in his father's footsteps and pursue a career in law. He halfheartedly enrolled in the City College of New York, where he entered the Students Army Training Corps in October 1918. His military experience was limited; Germany surrendered in early November, and Cukor's duty ended after only two months. He left school shortly afterwards.

Cukor obtained a job as an assistant stage manager and bit player with a touring production of The Better 'Ole, a popular British musical based on Old Bill, a cartoon character created by Bruce Bairnsfather. In 1920, he became the stage manager for the Knickerbocker Players, a troupe that shuttled between Syracuse and Rochester, New York, and the following year he was hired as general manager of the newly formed Lyceum Players, an upstate summer stock company. In 1925 he formed the C.F. and Z. Production Company with Walter Folmer and John Zwicki, which gave him his first opportunity to direct. Following their first season, he made his Broadway directorial debut with Antonia by Hungarian Playwright Melchior Lengyel, then returned to Rochester, where C.F. and Z. evolved into the Cukor-Kondolf Stock Company, a troupe that included Louis Calhern, Ilka Chase, Phyllis Povah, Frank Morgan, Reginald Owen, Elizabeth Patterson and Douglass Montgomery, all of whom worked with Cukor in later years in Hollywood. Lasting only one season with the company was Bette Davis. Cukor later recalled, "Her talent was apparent, but she did buck at direction. She had her own ideas, and though she only did bits and ingenue roles, she didn't hesitate to express them." For the next several decades, Davis claimed she was fired, and although Cukor never understood why she placed so much importance on an incident he considered so minor, he never worked with her again.

For the next few years, Cukor alternated between Rochester in the summer months and Broadway in the winter. His direction of a 1926 stage adaptation of The Great Gatsby by Owen Davis brought him to the attention of the New York critics. Writing in the Brooklyn Eagle, drama critic Arthur Pollock called it "an unusual piece of work by a Director not nearly so well known as he should be." Cukor directed six more Broadway productions before departing for Hollywood in 1929.

When Hollywood began to recruit New York theater talent for sound films, Cukor immediately answered the call. In December 1928, Paramount Pictures signed him to a contract that reimbursed him for his airfare and initially paid him $600 per week with no screen credit during a six-month apprenticeship. He arrived in Hollywood in February 1929, and his first assignment was to coach the cast of River of Romance to speak with an acceptable Southern accent. In October, the studio lent him to Universal Pictures to conduct the screen tests and work as a dialogue Director for All Quiet on the Western Front which was released in 1930. That year he co-directed three films at Paramount, and his weekly salary was increased to $1500. He made his solo directorial debut with Tarnished Lady (1931) starring Tallulah Bankhead.

By the mid-1930s, Cukor was not only established as a prominent Director but, socially, as an unofficial head of Hollywood's gay subculture. His home, redecorated in 1935 by gay actor-turned-interior designer william Haines with gardens designed by Florence Yoch & Lucile Council, was the scene of many gatherings for the industry's homosexuals. The close-knit group reputedly included Haines and his partner Jimmie Shields, Writer Somerset Maugham, Director James Vincent, Screenwriter Rowland Leigh, costume designers Orry-Kelly and Robert Le Maire, and actors John Darrow, Anderson Lawler, Grady Sutton, Robert Seiter and Tom Douglas. Frank Horn, secretary to Cary Grant, was also a frequent guest.

Cukor was then assigned to One Hour with You (1932), an operetta with Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald, when original Director Ernst Lubitsch opted to concentrate on producing the film instead. At first the two men worked well together, but two weeks into filming Lubitsch began arriving on the set on a regular basis, and he soon began directing scenes with Cukor's consent. Upon the film's completion, Lubitsch approached Paramount general manager B.P. Schulberg and threatened to leave the studio if Cukor's name wasn't removed from the credits. When Schulberg asked him to cooperate, Cukor filed suit. He eventually settled for being billed as assistant Director and then left Paramount to work with David O. Selznick at RKO Studios.

Cukor was hired to direct Gone with the Wind by Selznick in 1936, even before the book was published. He spent the next two years involved with pre-production, including supervision of the numerous screen tests of actresses anxious to portray Scarlett O'Hara. Cukor favored Hepburn for the role, but Selznick, concerned about her reputation as "box office poison", would not consider her without a screen test, and the Actress refused to film one. Of those who did, Cukor preferred Paulette Goddard, but her supposedly illicit relationship with Charlie Chaplin (they were, in fact, secretly married) concerned Selznick.

Selznick had already been unhappy with Cukor ("a very expensive luxury") for not being more receptive to directing other Selznick assignments, even though Cukor had remained on salary since early 1937; and in a confidential memo written in September 1938, four months before principal photography began, Selznick flirted with the idea of replacing him with Victor Fleming. "I think the biggest black mark against our management to date is the Cukor situation and we can no longer be sentimental about it.... We are a Business concern and not patrons of the arts..." Cukor was relieved of his duties, but he continued to work with Leigh and Olivia de Havilland off the set. Various rumors about the reasons behind his dismissal circulated throughout Hollywood. Selznick's friendship with Cukor had crumbled slightly when the Director refused other assignments, including A Star is Born (1937) and Intermezzo (1939). Given that Gable and Cukor had worked together before (on Manhattan Melodrama, 1934) and Gable had no objection to working with him then, and given Selznick's desperation to get Gable for Rhett Butler, if Gable had any objections to Cukor, certainly they would have been expressed before he signed his contract for the film. Yet, Writer Gore Vidal, in his autobiography Point to Point Navigation, recounted that Gable demanded that Cukor be fired off Wind because, according to Cukor, the young Gable had been a male hustler and Cukor had been one of his johns. This has been confirmed by Hollywood biographer E.J. Fleming, who has recounted that, during a particularly difficult scene, Gable erupted publicly, screaming: "I can't go on with this picture. I won't be directed by a fairy. I have to work with a real man."

Between his Wind chores, the Director assisted with other projects. He filmed the cave scene for The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1938), and, following the firing of its original Director Richard Thorpe, Cukor spent a week on the set of The Wizard of Oz (1939). Although he filmed no footage, he made crucial changes to the look of Dorothy by eliminating Judy Garland's blonde wig and adjusting her makeup and costume, encouraging her to act in a more natural manner. Additionally, Cukor softened the Scarecrow's makeup and gave Margaret Hamilton a different hairstyle for the Wicked Witch of the West as well as altered her makeup and other facial features. Cukor also suggested that the studio cast Jack Haley, on loan from 20th Century Fox, as the Tin Man.

Cukor's dismissal from Wind freed him to direct The Women (1939), which has an all-female cast, followed by The Philadelphia Story (1940). He also directed Greta Garbo, another of his favorite actresses, in Two-Faced Woman (1941), her last film before she retired from the screen.

Cukor quickly earned a reputation as a Director who could coax great performances from actresses and he became known as a "woman's director", a title he resented. Despite this reputation, during his career, he oversaw more performances honored with the Academy Award for Best Actor than any other director: James Stewart in The Philadelphia Story (1940), Ronald Colman in A Double Life (1947), and Rex Harrison in My Fair Lady (1964). One of Cukor's earlier ingenues was Actress Katharine Hepburn, who debuted in A Bill of Divorcement (1932) and whose looks and personality left RKO officials at a loss as to how to use her. Cukor directed her in several films, both successful, such as Little Women (1933) and Holiday (1938), and disastrous, such as Sylvia Scarlett (1935). Cukor and Hepburn became close friends off the set.

The remainder of the decade was a series of hits and misses for Cukor. Both Two-Faced Woman and Her Cardboard Lover (1942) were commercial failures. More successful were A Woman's Face (1941) with Joan Crawford and Gaslight (1944) with Ingrid Bergman and Charles Boyer. During this era, Cukor forged an alliance with screenwriters Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon, who had met in Cukor's home in 1939 and married three years later. Over the course of seven years, the trio collaborated on seven films, including A Double Life (1947) starring Ronald Colman, Adam's Rib (1949), Born Yesterday (1950), The Marrying Kind (1952), and It Should Happen to You (1954), all featuring Judy Holliday, another Cukor favorite, who won the Academy Award for Best Actress for Born Yesterday.

It was an open secret in Hollywood that Cukor was gay, at a time when society was against it, although he was discreet about his sexual orientation and "never carried it as a pin on his lapel," as Producer Joseph L. Mankiewicz put it. He was a celebrated bon vivant whose luxurious home was the site of weekly Sunday afternoon parties attended by closeted celebrities and the attractive young men they met in bars and gyms and brought with them. At least once, in the midst of his reign at MGM, he was arrested on vice charges, but studio executives managed to get the charges dropped and all records of it expunged, and the incident was never publicized by the press. In the late 1950s, Cukor became involved with a considerably younger man named George Towers. He financed his education at the Los Angeles State College of Applied Arts and Sciences and the University of Southern California, from which Towers graduated with a law degree in 1967. That fall Towers married a woman, and his relationship with Cukor evolved into one of father and son, and for the remainder of Cukor's life the two remained very close.

In December 1952, Cukor was approached by Sid Luft, who proposed the Director helm a musical remake of A Star is Born (1937) with his then-wife Judy Garland in the lead role. Cukor had declined to direct the earlier film because it was too similar to his own What Price Hollywood? (1932), but the opportunity to direct his first Technicolor film, first musical, and work with Screenwriter Moss Hart and especially Garland appealed to him, and he accepted. Getting the updated A Star Is Born (1954) to the screen proved to be a challenge. Cukor wanted Cary Grant for the male lead and went so far as to read the entire script with him, but Grant, while agreeing it was the role of a lifetime, steadfastly refused to do it, and Cukor never forgave him. The Director then suggested either Humphrey Bogart or Frank Sinatra tackle the part, but Jack L. Warner rejected both. Stewart Granger was the front Runner for a period of time, but he backed out when he was unable to adjust to Cukor's habit of acting out scenes as a form of direction. James Mason eventually was contracted, and filming began on October 12, 1953. As the months passed, Cukor was forced to deal not only with constant script changes but a very unstable Garland, who was plagued by chemical and alcohol dependencies, extreme weight fluctuations, and real and imagined illnesses. In March 1954, a rough cut still missing several musical numbers was assembled, and Cukor had mixed feelings about it. When the last scene finally was filmed in the early morning hours of July 28, 1954, Cukor already had departed the production and was unwinding in Europe. The first preview the following month ran 210 minutes and, despite ecstatic feedback from the audience, Cukor and Editor Folmar Blangsted trimmed it to 182 minutes for its New York premiere in October. The reviews were the best of Cukor's career, but Warner executives, concerned the running time would limit the number of daily showings, made drastic cuts without Cukor, who had departed for Pakistan to scout locations for the epic Bhowani Junction in 1954-1955. At its final running time of 154 minutes, the film had lost musical numbers and crucial dramatic scenes, and Cukor called it "very painful." He was not included in the film's six Oscar nominations.

Over the next ten years, Cukor directed a handful of films with varying success. Les Girls (1957) won the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy, and Wild Is the Wind (1957) earned Oscar nominations for Anna Magnani and Anthony Quinn, but neither Heller in Pink Tights nor Let's Make Love (both 1960) were box office hits. Another project during this period was the ill-fated Something's Got to Give, an updated remake of the comedy My Favorite Wife (1940). Cukor liked leading lady Marilyn Monroe but found it difficult to deal with her erratic work habits, frequent absences from the set, and the constant presence of her acting coach Paula Strasberg. After 32 days of shooting, the Director had only 7½ minutes of usable film. Then Monroe travelled to New York to appear at a birthday celebration for John F. Kennedy at Madison Square Garden, where she serenaded the President. Studio documents released after Monroe's death confirmed that her appearance at the political fundraising event was approved by Fox executives. The production came to a halt when Cukor had filmed every scene not involving Monroe and the Actress remained unavailable. 20th Century Fox executive Peter Levathes fired her and hired Lee Remick to replace her, prompting co-star Dean Martin to quit because his contract guaranteed he would be playing opposite Monroe. With the production already $2 million over budget and everyone back at the starting gate, the studio pulled the plug on the project. Less than two months later, Monroe was found dead in her home.

Two years later, Cukor achieved one of his greatest successes with My Fair Lady (1964). Throughout filming there were mounting tensions between the Director and designer Cecil Beaton, but Cukor was thrilled with leading lady Audrey Hepburn, although the crew was less enchanted with her diva-like demands. Although several reviews were critical of the film – Pauline Kael said it "staggers along" and Stanley Kauffmann thought Cukor's direction was like "a rich gravy poured over everything, not remotely as delicately rich as in the Asquith-Howard 1937 [sic] Pygmalion" — the film was a box office hit which won him the Academy Award for Best Director, the Golden Globe Award for Best Director, and the Directors Guild of America Award after having been nominated for each several times.

Following My Fair Lady, Cukor became less active. He directed Maggie Smith in Travels with My Aunt (1972) and helmed the critical and commercial flop The Blue Bird (1976), the first joint Soviet-American production. He reunited twice with Katharine Hepburn for the television movies Love Among the Ruins (1975) and The Corn Is Green (1979). He directed Rich and Famous (1981), his final film, with Jacqueline Bisset and Candice Bergen, at the age of 82.

In 1976, Cukor was awarded the George Eastman Award, given by George Eastman House for distinguished contribution to the art of film.

Cukor died of a heart attack on January 24, 1983, and was interred in Grave D, Little Garden of Constancy, Garden of Memory (private), Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale), California. Records in probate court indicated his net worth at the time of his death was $2,377,720.

The PBS series American Masters produced a comprehensive documentary about his life and work titled On Cukor directed by Robert Trachtenberg in 2000.

In 2013, The Film Society of Lincoln Center presented a comprehensive weeks-long retrospective of his work entitled "The Discreet Charm of George Cukor."