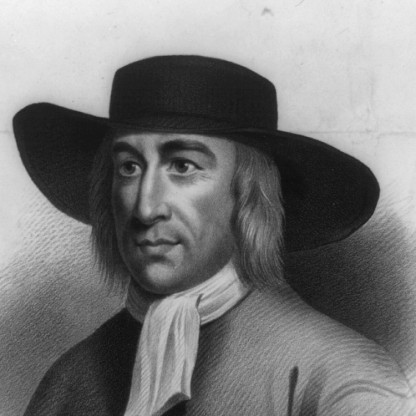

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Author |

| Birth Year | 1624 |

| Birth Place | Leicestershire, Kingdom of England, British |

| Age | 395 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 13 January 1691 (aged 66)\nLondon, England |

| Church | Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) |

| Denomination | Quaker |

| Parents | Christopher Fox (father) and Mary Lago (mother) |

| Spouse | Margaret Fell (née Askew) |

| Occupation | Founder and religious leader of Quakers |

Net worth: $18 Million (2024)

George Fox, a well-known British author, is estimated to have a net worth of $18 million in the year 2024. As an accomplished writer, Fox has gained fame and fortune through his literary works. His dedication and talent have propelled him to success in the competitive field of literature, and his works have resonated with readers around the world. With his impressive net worth, George Fox has undoubtedly become a significant figure in the literary world, leaving a lasting impact on the British writing scene.

Famous Quotes:

as I had forsaken the priests, so I left the separate preachers also, and those esteemed the most experienced people; for I saw there was none among them all that could speak to my condition. And when all my hopes in them and in all men were gone, so that I had nothing outwardly to help me, nor could tell what to do, then, oh, then, I heard a voice which said, "There is one, even Christ Jesus, that can speak to thy condition"; and when I heard it my heart did leap for joy. Then the Lord let me see why there was none upon the earth that could speak to my condition, namely, that I might give Him all the glory; for all are concluded under sin, and shut up in unbelief as I had been, that Jesus Christ might have the pre-eminence who enlightens, and gives grace, and faith, and power. Thus when God doth work, who shall let (i.e. prevent) it? And this I knew experimentally.

Biography/Timeline

Driven by his "inner voice", Fox left Drayton-in-the-Clay in September 1643, moving toward London in a state of mental torment and confusion. The English Civil War had begun and troops were stationed in many towns through which he passed. In Barnet, he was torn by depression (perhaps from the temptations of the resort town near London). He alternately shut himself in his room for days at a time or went out alone into the countryside. After almost a year he returned to Drayton, where he engaged Nathaniel Stephens, the clergyman of his hometown, in long discussions on religious matters. Stephens considered Fox a gifted young man but the two disagreed on so many issues that he later called Fox mad and spoke against him.

In 1647 Fox began to preach publicly: in market-places, fields, appointed meetings of various kinds or even sometimes "steeple-houses" after the Service. His powerful preaching began to attract a small following. It is not clear at what point the Society of Friends was formed but there was certainly a group of people who often travelled together. At first, they called themselves "Children of the Light" or "Friends of the Truth", and later simply "Friends". Fox seems to have initially had no Desire to found a sect but only to proclaim what he saw as the pure and genuine principles of Christianity in their original simplicity, though he afterward showed great prowess as a religious legislator in the organization he gave to the new society.

Fox complained to judges about decisions he considered morally wrong, as in his letter on the case of a woman due to be executed for theft. He campaigned against the paying of tithes, which funded the established church and often went into the pockets of absentee landlords or religious colleges far away from the paying parishioners. In his view, as God was everywhere and anyone could preach, the established church was unnecessary and a university qualification irrelevant for a preacher. Conflict with civil authority was inevitable. Fox was imprisoned several times, the first at Nottingham in 1649. At Derby in 1650 he was imprisoned for blasphemy; a judge mocked Fox's exhortation to "tremble at the word of the Lord", calling him and his followers "Quakers". Following his refusal to fight against the return of the monarchy (or to take up arms for any reason), his sentence was doubled. The refusal to swear oaths or take up arms came to be a much more important part of his public statements. Refusal to take oaths meant that Quakers could be prosecuted under laws compelling subjects to pledge allegiance, as well as making testifying in court problematic. In a letter of 1652 (That which is set up by the sword), he urged Friends not to use "carnal weapons" but "spiritual weapons", saying "let the waves [the power of nations] break over your heads".

The 1650s, when the Friends were most confrontational, was one of the most creative periods of their history. During the Commonwealth, Fox had hoped that the movement would become the major church in England. Disagreements, persecution and increasing social turmoil, however, led Fox to suffer from a severe depression, which left him deeply troubled at Reading, Berkshire, for ten weeks in 1658 or 1659. In 1659, he sent parliament his most politically radical pamphlet, Fifty nine Particulars laid down for the Regulating things, but the year was so chaotic that it never considered them; the document was not reprinted until the 21st century.

There were a great many rival Christian denominations holding very diverse opinions; the atmosphere of dispute and confusion gave Fox an opportunity to put forward his own beliefs through his personal sermons. Fox's preaching was grounded in scripture but was mainly effective because of the intense personal experience he was able to project. He was scathing about immorality, deceit and the exacting of tithes and urged his listeners to lead lives without sin, avoiding the Ranter's antinomian view that a believer becomes automatically sinless. By 1651 he had gathered other talented Preachers around him and continued to roam the country despite a harsh reception from some listeners, who would whip and beat them to drive them away. As his reputation spread, his words were not welcomed by all. As an uncompromising preacher, he hurled disputation and contradiction to the faces of his opponents. The worship of Friends in the form of silent waiting punctuated by individuals speaking as the Spirit moved them seems to have been well-established by this time, though it is not recorded how this came to be; Richard Bauman asserts that "speaking was an important feature of the meeting for worship from the earliest days of Quakerism."

In 1652, Fox preached for several hours under a walnut tree at Balby, where his disciple Thomas Aldham was instrumental in setting up the first meeting in the Doncaster area. In the same year Fox felt that God led him to ascend Pendle Hill where he had a vision of many souls coming to Christ. From there he travelled to Sedbergh, where he had heard a group of Seekers were meeting, and preached to over a thousand people on Firbank Fell, convincing many, including Francis Howgill, to accept that Christ might speak to people directly. At the end of the month he stayed at Swarthmoor Hall, near Ulverston, the home of Thomas Fell, vice-chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and his wife, Margaret. At around this time the ad hoc meetings of Friends began to be formalized and a monthly meeting was set up in County Durham. Margaret became a Quaker and, although Thomas did not convert, his familiarity with the Friends proved influential when Fox was arrested for blasphemy in October. Fell was one of three presiding judges, and had the charges dismissed on a technicality.

Fox remained at Swarthmoor until summer 1653 then left for Carlisle where he was arrested again for blasphemy. It was even proposed to put him to death but Parliament requested his release rather than have "a young man ... die for religion". Further imprisonments came at London, England in 1654, Launceston in 1656, Lancaster in 1660, Leicester in 1662, Lancaster again and Scarborough in 1664–66 and Worcester in 1673–75. Charges usually included causing a disturbance and travelling without a pass. Quakers fell foul of irregularly enforced laws forbidding unauthorized worship while actions motivated by belief in social equality—refusing to use or acknowledge titles, take hats off in court or bow to those who considered themselves socially superior—were seen as disrespectful. While imprisoned at Launceston Fox wrote, "Christ our Lord and master saith 'Swear not at all, but let your communications be yea, yea, and nay, nay, for whatsoever is more than these cometh of evil.' ... the Apostle James saith, 'My brethren, above all things swear not, neither by heaven, nor by earth, nor by any other oath. Lest ye fall into condemnation.'"

One early Quaker convert, the Yorkshireman James Nayler, arose as a prominent preacher in London around 1655. A breach began to form between Fox's and Nayler's followers. As Fox was held prisoner at Launceston, Nayler moved south-westwards towards Launceston intending to meet Fox and heal any rift. On the way he was arrested himself and held at Exeter. After Fox was released from Launceston gaol in 1656, he preached throughout the West Country. Arriving at Exeter late in September, Fox was reunited with Nayler. Nayler and his followers refused to remove their hats while Fox prayed, which Fox took as both a personal slight and a bad Example. When Nayler refused to kiss Fox's hand, Fox told Nayler to kiss his foot instead. Nayler was offended and the two parted acrimoniously. Fox wrote, "there was now a wicked spirit risen amongst Friends".

Fox petitioned Cromwell over the course of 1656, asking him to alleviate the persecution of Quakers. Later that year, they met for a second time at Whitehall. On a personal level, the meeting went well; despite disagreements between the two men, they had a certain rapport. Fox invited Cromwell to "lay down his crown at the feet of Jesus"—which Cromwell declined to do. Fox met Cromwell again twice in March 1657. Their last meeting was in 1658 at Hampton Court, though they could not speak for long or meet again because of the Protector's worsening illness—Fox even wrote that "he looked like a dead man". Cromwell died in September of that year.

At least on one point, Charles listened to Fox. The seven hundred Quakers who had been imprisoned under Richard Cromwell were released, though the government remained uncertain about the group's links with other, more violent, movements. A revolt by the Fifth Monarchists in January 1661 led to the suppression of that sect and the repression of other Nonconformists, including Quakers. In the aftermath of this attempted coup, Fox and eleven other Quakers issued a broadside proclaiming what became known among Friends in the 20th century as the "peace testimony": they committed themselves to oppose all outward wars and strife as contrary to the will of God. Not all his followers accepted this statement; Isaac Penington, for Example, dissented for a time arguing that the state had a duty to protect the innocent from evil, if necessary by using military force. Despite the testimony, persecution against Quakers and other dissenters continued.

Parliament enacted laws which forbade non-Anglican religious meetings of more than five people, essentially making Quaker meetings illegal. Fox counseled his followers to openly violate laws that attempted to suppress the movement, and many Friends, including women and children, were jailed over the next two and a half decades. Meanwhile, Quakers in New England had been banished (and some executed), and Charles was advised by his councillors to issue a mandamus condemning this practice and allowing them to return. Fox was able to meet some of the New England Friends when they came to London, stimulating his interest in the colonies. Fox was unable to travel there immediately: he was imprisoned again in 1664 for his refusal to swear the oath of allegiance, and on his release in 1666 was preoccupied with organizational matters—he normalized the system of monthly and quarterly meetings throughout the country, and extended it to Ireland.

Fox married Margaret Fell of Swarthmoor Hall, a lady of high social position and one of his early converts, on 27 October 1669 at a meeting in Bristol. She was ten years his senior and had eight children (all but one of them Quakers) by her first husband, Thomas Fell, who had died in 1658. She was herself very active in the movement, and had campaigned for equality and the acceptance of women as Preachers. As there were no Priests at Quaker weddings to perform the ceremony, the union took the form of a civil marriage approved by the principals and the witnesses at a meeting. Ten days after the marriage, Margaret returned to Swarthmoor to continue her work there while George went back to London. Their shared religious work was at the heart of their life together, and they later collaborated on a great deal of the administration the Society required. Shortly after the marriage, Margaret was imprisoned at Lancaster; George remained in the south-east of England, becoming so ill and depressed that for a time he lost his sight.

By 1671 Fox had recovered and Margaret had been released by order of the King. Fox resolved to visit the English settlements in America and the West Indies, remaining there for two years, possibly to counter any remnants of Perrot's teaching there. After a voyage of seven weeks, during which dolphins were caught and eaten, the party arrived in Barbados on 3 October 1671. From there, Fox sent an epistle to Friends spelling out the role of women's meetings in the Quaker marriage ceremony, a point of controversy when he returned home. One of his proposals suggested that the prospective couple should be interviewed by an all-female meeting prior to the marriage to determine whether there were any financial or other impediments. Though women's meetings had been held in London for the last ten years, this was an innovation in Bristol and the north-west of England, which many there felt went too far.

Following extensive travels around the various American colonies, George Fox returned to England in June 1673 confident that his movement was firmly established there. Back in England, however, he found his movement sharply divided among provincial Friends (such as william Rogers, John Wilkinson and John Story) who resisted establishment of women's meetings and the power of those who resided in or near London. With william Penn and Robert Barclay as allies of Fox, the challenge to Fox's leadership was eventually put down. But in the midst of the dispute, Fox was imprisoned again for refusing to swear oaths after being captured at Armscote, Worcestershire. His mother died shortly after hearing of his arrest and Fox's health began to suffer. Margaret Fell petitioned the king for his release, which was granted, but Fox felt too weak to take up his travels immediately. Recuperating at Swarthmoor, he began dictating what would be published after his death as his journal and devoted his time to his written output: letters, both public and private, as well as books and essays. Much of his Energy was devoted to the topic of oaths, having become convinced of its importance to Quaker ideas. By refusing to swear, he felt that he could bear witness to the value of truth in everyday life, as well as to God, who he associated with truth and the inner light.

The Society of Friends became increasingly organized towards the end of the decade. Large meetings were held, including a three-day event in Bedfordshire, the precursor of the present Britain Yearly Meeting system. Fox commissioned two Friends to travel around the country collecting the testimonies of imprisoned Quakers, as evidence of their persecution; this led to the establishment in 1675 of Meeting for Sufferings, which has continued to the present day.

For three months in 1677 and a month in 1684, Fox visited the Friends in the Netherlands, and organized their meetings for discipline. The first trip was the more extensive, taking him into what is now Germany, proceeding along the coast to Friedrichstadt and back again over several days. Meanwhile, Fox was participating in a dispute among Friends in Britain over the role of women in meetings, a struggle which took much of his Energy and left him exhausted. Returning to England, he stayed in the south in order to try to end the dispute. He followed the foundation of the colony of Pennsylvania, where Penn had given him over 1,000 acres (4.0 km) of land, with interest. Persecution continued, with Fox arrested briefly in October 1683. Fox's health was becoming worse, but he continued his activities—writing to Leaders in Poland, Denmark, Germany, and elsewhere about his beliefs, and their treatment of Quakers.

In the last years of his life, Fox continued to participate in the London Meetings, and still made representations to Parliament about the sufferings of Friends. The new King, James II, pardoned religious dissenters jailed for failure to attend the established church, leading to the release of about 1,500 Friends. Though the Quakers lost influence after the Glorious Revolution, which deposed James II, the Act of Toleration 1689 put an end to the uniformity laws under which Quakers had been persecuted, permitting them to assemble freely.

Two days after preaching, as usual, at the Gracechurch Street Meeting House in London, George Fox died between 9 and 10 p.m. on 13 January 1691. He was interred in the Quaker Burying Ground, Bunhill Fields, three days later in the presence of thousands of mourners.

Fox's journal was first published in 1694, after editing by Thomas Ellwood—a friend and associate of John Milton—with a preface by william Penn. Like most similar works of its time the journal was not written contemporaneously to the events it describes, but rather compiled many years later, much of it dictated. Parts of the journal were not in fact by Fox at all but are constructed by its editors from diverse sources and written as if by him. The dissent within the movement and the contributions of others to the development of Quakerism are largely excluded from the narrative. Fox portrays himself as always in the right and always vindicated by God's interventions on his behalf. As a religious autobiography, Rufus Jones compared it to such works as Augustine's Confessions and John Bunyan's Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners. It is, though, an intensely personal work with little dramatic power that only succeeds in appealing to readers after substantial editing. Historians have used it as a primary source because of its wealth of detail on ordinary life in the 17th century, and the many towns and villages which Fox visited.

After Nayler's own release later the same year he rode into Bristol triumphantly playing the part of Jesus Christ in a re-enactment of Palm Sunday. He was arrested and taken to London, where Parliament defeated a motion to execute him by 96–82. Instead, they ordered that he be pilloried and whipped through both London and Bristol, branded on his forehead with the letter B (for blasphemer), bored through the tongue with a red-hot iron and imprisoned in solitary confinement with hard labour. Nayler was released in 1659, but he was a broken man. On meeting Fox in London, he fell to his knees and begged Fox's forgiveness. Shortly afterward, Nayler was attacked by thieves while travelling home to his family, and died.

Walt Whitman, who was raised by parents inspired by Quaker principles, later wrote: "George Fox stands for something too—a thought—the thought that wakes in silent hours—perhaps the deepest, most eternal thought latent in the human soul. This is the thought of God, merged in the thoughts of moral right and the immortality of identity. Great, great is this thought—aye, greater than all else."