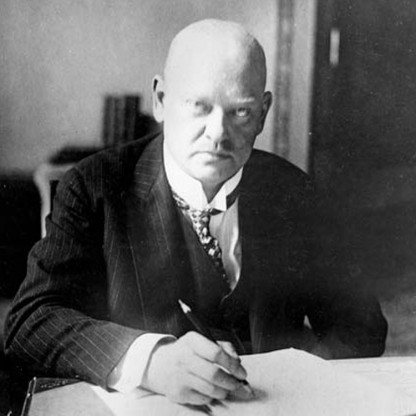

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Chancellor of Germany |

| Birth Day | May 10, 1878 |

| Birth Place | Berlin, German |

| Age | 141 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 3 October 1929(1929-10-03) (aged 51)\nBerlin |

| Birth Sign | Gemini |

| President | Friedrich Ebert |

| Preceded by | Hans von Rosenberg |

| Succeeded by | Julius Curtius |

| Chancellor | Himself Wilhelm Marx Hans Luther Hermann Müller |

| Political party | National Liberal Party (1907–1918) German Democratic Party (1918) German People's Party (1918–1929) |

| Spouse(s) | Käte Kleefeld |

| Children | Wolfgang Hans-Joachim |

Net worth: $5 Million (2024)

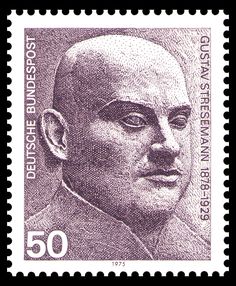

Gustav Stresemann, the renowned German politician who served as Chancellor of Germany, is estimated to have a net worth of $5 million in 2024. Stresemann played a significant role in the Weimar Republic period, famously advocating for stability and reconciliation between Germany and its international counterparts following World War I. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1926 for his efforts in establishing the Locarno Treaties, which aimed at resolving territorial disputes and maintaining peace in Europe. Stresemann's political influence and economic expertise likely contributed to his accumulated wealth, making him a prominent figure in German history.

Famous Quotes:

If the allies had obliged me just one single time, I would have brought the German people behind me, yes; even today, I could still get them to support me. However, they (the allies) gave me nothing and the minor concessions they made, always came too late. Thus, nothing else remains for us but brutal force. The future lies in the hands of the new generation. Moreover, they, the German youth, who we could have won for peace and reconstruction, we have lost. Herein lies my tragedy and there, the allies' crime.

— Stresemann, to diplomat Sir Albert Bruce Lockhart in 1928

Biography/Timeline

Stresemann was born on 10 May 1878 in the Köpenicker Straße area of southeast Berlin, the youngest of seven children. His father worked as a beer bottler and distributor, and also ran a small bar out of the family home, as well as renting rooms for extra money. The family was lower middle class, but relatively well-off for the neighbourhood, and had sufficient funds to provide Gustav with a high-quality education. Stresemann was an excellent student, particularly excelling in German literature and poetry. In an essay written when he left school, he noted that he would have enjoyed becoming a Teacher, but he would only have been qualified to teach languages or the natural sciences, which were not his primary areas of interest. Thus, he entered the University of Berlin in 1897 to study political economy. Through this course of studies, Stresemann was exposed to the principal ideological arguments of his day, particularly the German debate about socialism.

During his university years, Stresemann also became active in Burschenschaften movement of student fraternities, and became Editor, in April 1898, of the Allgemeine Deutsche Universitäts-Zeitung, a newspaper run by Konrad Kuster, a leader in the liberal portion of the Burschenschaften. His editorials for the paper were often political, and dismissed most of the contemporary political parties as broken in one way or another. In these early writings, he set out views that combined liberalism with strident nationalism, a combination that would dominate his views for the rest of his life. In 1898, Stresemann left the University of Berlin, transferring to the University of Leipzig so that he could pursue a doctorate. He completed his studies in January 1901, submitting a thesis on the bottled beer industry in Berlin, which received a relatively high grade. Stresemann's doctoral supervisor was the Economist Karl Bücher.

In 1902 he founded the Saxon Manufacturers' Association. In 1903 he married Käte Kleefeld (1883–1970), daughter of a wealthy Jewish Berlin businessman, and the sister of Kurt von Kleefeld, the last person in Germany to be ennobled (in 1918). At that time he was also a member of Friedrich Naumann's National-Social Association. In 1906 he was elected to the Dresden town council. Though he had initially worked in trade associations, Stresemann soon became a leader of the National Liberal Party in Saxony. In 1907, he was elected to the Reichstag, where he soon became a close associate of party chairman Ernst Bassermann. However, his support of expanded social-welfare programs did not sit well with some of the party's more conservative members, and he lost his post in the party's executive committee in 1912. Later that year he lost both his Reichstag and town council seats. He returned to Business and founded the German-American Economic Association. In 1914 he returned to the Reichstag. He was exempted from war Service due to poor health. With Bassermann kept away from the Reichstag by either illness or military Service, Stresemann soon became the National Liberals' de facto leader. After Bassermann's death in 1917, Stresemann succeeded him as the party leader.

During his period in the foreign ministry, Stresemann came more and more to accept the Republic, which he had at first rejected. By the mid-1920s, having contributed much to a (temporary) consolidation of the feeble democratic order, Stresemann was regarded as a Vernunftrepublikaner (republican by reason) - someone who accepted the Republic as the least of all evils, but was in his heart still loyal to the monarchy. The conservative opposition criticized him for his supporting the republic and fulfilling too willingly the demands of the Western powers. Along with Matthias Erzberger and others, he was attacked as a Erfüllungspolitiker ("fulfillment politician"). Indeed, some of the more conservative members of his own People's Party never really trusted him.

Stresemann was not, however, in any sense pro-French. His main preoccupation was how to free Germany from the burden of reparations payments to Britain and France, imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. His strategy for this was to forge an economic alliance with the United States. The U.S. was Germany's main source of food and raw materials, and one of Germany's largest export markets for manufactured goods. Germany's economic recovery was thus in the interests of the U.S., and gave the U.S. an incentive to help Germany escape from the reparations burden. The Dawes and Young plans were the result of this strategy. Stresemann had a close relationship with Herbert Hoover, who was Secretary of Commerce in 1921-28 and President from 1929. This strategy worked remarkably well until it was derailed by the Great Depression after Stresemann's death.

Stresemann remained as Foreign Minister in the government of his successor, Centrist Wilhelm Marx. He remained foreign minister for the rest of his life in eight successive governments ranging from the centre-right to the centre-left. As Foreign Minister, Stresemann had numerous achievements. His first notable achievement was the Dawes Plan of 1924, which reduced Germany's overall reparations commitment and reorganized the Reichsbank.

In 1925, when he first proposed an agreement with France, he made it clear that in doing so he intended to "gain a free hand to secure a peaceful change of the borders in the East and [...] concentrate on a later incorporation of German territories in the East". In the same year, while Poland was in a state of political and economic crisis, Stresemann began a trade war against the country. Stresemann hoped for an escalation of the Polish crisis, which would enable Germany to regain territories ceded to Poland after World War I, and he wanted Germany to gain a larger market for its products there. So Stresemann refused to engage in any international cooperation that would have "prematurely" restabilized the Polish economy. In response to a British proposal, Stresemann wrote to the German ambassador in London: "[A] final and lasting recapitalization of Poland must be delayed until the country is ripe for a settlement of the border according to our wishes and until our own position is sufficiently strong". According to Stresemann's letter, there should be no settlement "until [Poland's] economic and financial distress has reached an extreme stage and reduced the entire Polish body politic to a state of powerlessness". Stresseman hoped to annex Polish territories in Greater Poland, take over whole eastern Upper Silesia and parts of Central Silesia and the entire so called Polish Corridor. Besides waging economic war on Poland, Streseman funded extensive propaganda efforts and plotted to collaborate with Soviet Union against Polish statehood.

Stresemann was co-winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1926 for these achievements.

Germany signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact in August 1928. It renounced the use of violence to resolve international conflicts. Although Stresemann did not propose the pact, Germany's adherence convinced many people that Weimar Germany was a Germany that could be reasoned with. This new insight was instrumental in the Young Plan of February 1929 which led to more reductions in German reparations payment.

Gustav Stresemann died of a stroke on 3 October 1929 at the age of 51. His gravesite is situated in the Luisenstadt Cemetery at Südstern in Berlin Kreuzberg, and includes work by the German Sculptor Hugo Lederer. Stresemann's sudden and premature death, as well as the death of his "pragmatic moderate" French counterpart Aristide Briand in 1932, and the assassination of Briand's successor Louis Barthou in 1934, left a vacuum in European statesmanship that did not decelerate the movement towards renewed conflict, and ultimately World War II.

Stresemann briefly joined the German Democratic Party after the war, but was expelled for his association with the right wing. He then gathered the main body of the old National Liberal Party—including most of its centre and right factions—into the German People's Party (German: Deutsche Volkspartei, DVP), with himself as chairman. Most of its support came from middle class and upper class Protestants. The DVP platform promoted Christian family values, secular education, lower tariffs, opposition to welfare spending and agrarian subsidies and hostility to "Marxism" (that is, the Communists, and also the Social Democrats).