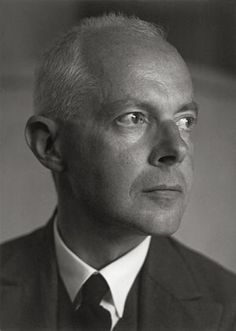

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Composer |

| Birth Day | September 18, 1921 |

| Birth Place | Cheltenham, British |

| Age | 99 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | May 25, 1934 |

| Birth Sign | Libra |

Net worth

Gustavus Theodore von Holst, renowned as a composer in British musical history, is said to have a net worth ranging between $100,000 and $1 million by the year 2024. Holst has left an indelible mark on the classical music scene, particularly with his iconic work "The Planets," a seven-movement orchestral suite. His innovative style and visionary compositions have gained him global recognition, making him one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. With such a significant net worth, von Holst has undoubtedly secured his place as a legendary figure in the world of music.

Biography/Timeline

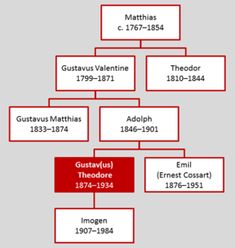

Holst's great-grandfather, Matthias Holst, born in Riga, Latvia, was of German origin; he served as Composer and harp-teacher to the Imperial Russian Court in St Petersburg. Matthias's son Gustavus, who moved to England with his parents as a child in 1802, was a Composer of salon-style music and a well-known harp Teacher. He appropriated the aristocratic prefix "von" and added it to the family name in the hope of gaining enhanced prestige and attracting pupils.

Holst's father, Adolph von Holst, became organist and choirmaster at All Saints' Church, Cheltenham; he also taught, and gave piano recitals. His wife, Clara, a former pupil, was a talented singer and Pianist. They had two sons; Gustav's younger brother, Emil Gottfried, became known as Ernest Cossart, a successful actor in the West End, New York and Hollywood. Clara died in February 1882, and the family moved to another house in Cheltenham, where Adolph recruited his sister Nina to help raise the boys. Gustav recognised her devotion to the family and dedicated several of his early compositions to her. In 1885 Adolph married Mary Thorley Stone, another of his pupils. They had two sons, Matthias (known as "Max") and Evelyn ("Thorley"). Mary von Holst was absorbed in Theosophy and not greatly interested in domestic matters. All four of Adolph's sons were subject to what one biographer calls "benign neglect", and Gustav in particular was "not overburdened with attention or understanding, with a weak sight and a weak chest, both neglected—he was 'miserable and scared'."

Holst was taught to play the piano and the violin; he enjoyed the former but hated the latter. At the age of twelve he took up the trombone at Adolph's suggestion, thinking that playing a brass instrument might improve his asthma. Holst was educated at Cheltenham Grammar School between 1886 and 1891. He started composing in or about 1886; inspired by Macaulay's poem Horatius he began, but soon abandoned, an ambitious setting of the work for chorus and orchestra. His early compositions included piano pieces, organ voluntaries, songs, anthems and a symphony (from 1892). His main influences at this stage were Mendelssohn, Chopin, Grieg and above all Sullivan.

After Holst left school in 1891, Adolph paid for him to spend four months in Oxford studying counterpoint with George Frederick Sims, organist of Merton College. On his return, Holst obtained his first professional appointment, aged seventeen, as organist and choirmaster at Wyck Rissington, Gloucestershire. The post brought with it the conductorship of the Bourton-on-the-Water Choral Society, which offered no extra remuneration but provided valuable experience that enabled him to hone his conducting skills. In November 1891 Holst gave what was perhaps his first public performance as a pianist; he and his father played the Brahms Hungarian Dances at a concert in Cheltenham. The programme for the event gives his name as "Gustav" rather than "Gustavus"; he was called by the shorter version from his early years.

Like many Musicians of his generation, Holst came under Wagner's spell. He had recoiled from the music of Götterdämmerung when he heard it at Covent Garden in 1892, but encouraged by his friend and fellow-student Fritz Hart he persevered and quickly became an ardent Wagnerite. Wagner supplanted Sullivan as the main influence on his music, and for some time, as Imogen put it, "ill-assimilated wisps of Tristan inserted themselves on nearly every page of his own songs and overtures." Stanford admired some of Wagner's works, and had in his earlier years been influenced by him, but Holst's sub-Wagnerian compositions met with his disapprobation: "It won't do, me boy; it won't do". Holst respected Stanford, describing him to a fellow-pupil, Herbert Howells, as "the one man who could get any one of us out of a technical mess", but he found that his fellow students, rather than the faculty members, had the greater influence on his development.

The year 1895 was also the bicentenary of Henry Purcell, which was marked by various performances including Stanford conducting Dido and Aeneas at the Lyceum Theatre; the work profoundly impressed Holst, who over twenty years later confessed to a friend that his search for "the (or a) musical idiom of the English language" had been inspired "unconsciously" by "hearing the recits in Purcell's Dido".

To support himself during his studies Holst played the trombone professionally, at seaside resorts in the summer and in London theatres in the winter. His daughter and biographer, Imogen Holst, records that from his fees as a player "he was able to afford the necessities of life: board and lodging, manuscript paper, and tickets for standing room in the gallery at Covent Garden Opera House on Wagner evenings". He secured an occasional engagement in symphony concerts, playing in 1897 under the baton of Richard Strauss at the Queen's Hall.

Occasional successes notwithstanding, Holst found that "man cannot live by composition alone"; he took posts as organist at various London churches, and continued playing the trombone in theatre orchestras. In 1898 he was appointed first trombonist and répétiteur with the Carl Rosa Opera Company and toured with the Scottish Orchestra. Though a capable rather than a virtuoso player he won the praise of the leading Conductor Hans Richter, for whom he played at Covent Garden. His salary was only just enough to live on, and he supplemented it by playing in a popular orchestra called the "White Viennese Band", conducted by Stanislas Wurm. Holst enjoyed playing for Wurm, and learned much from him about drawing rubato from players. Nevertheless, longing to devote his time to composing, Holst found the necessity of playing for "the Worm" or any other light orchestra "a wicked and loathsome waste of time". Vaughan Williams did not altogether agree with his friend about this; he admitted that some of the music was "trashy" but thought it had been useful to Holst nonetheless: "To start with, the very worst a trombonist has to put up with is as nothing compared to what a church organist has to endure; and secondly, Holst is above all an orchestral Composer, and that sure touch which distinguishes his orchestral writing is due largely to the fact that he has been an orchestral player; he has learnt his art, both technically and in substance, not at second hand from text books and Models, but from actual live experience."

Holst's settings of Indian texts formed only a part of his compositional output in the period 1900 to 1914. A highly significant factor in his musical development was the English folksong revival, evident in the orchestral suite A Somerset Rhapsody (1906–07), a work that was originally to be based around eleven folksong themes; this was later reduced to four. Observing the work's kinship with Vaughan Williams's Norfolk Rhapsody, Dickinson remarks that, with its firm overall structure, Holst's composition "rises beyond the level of ... a song-selection". Imogen acknowledges that Holst's discovery of English folksongs "transformed his orchestral writing", and that the composition of A Somerset Rhapsody did much to banish the chromaticisms that had dominated his early compositions. In the Two Songs without Words of 1906, Holst showed that he could create his own original music using the folk idiom. An orchestral folksong fantasy Songs of the West, also written in 1906, was withdrawn by the Composer and never published, although it emerged in the 1980s in the form of an arrangement for wind band by James Curnow.

Holst's interest in Indian mythology, shared by many of his contemporaries, first became musically evident in the opera Sita (1901–06). During the opera's long gestation, Holst worked on other Indian-themed pieces. These included Maya (1901) for violin and piano, regarded by the Composer and Writer Raymond Head as "an insipid salon-piece whose musical language is dangerously close to Stephen Adams". Then, through Vaughan Williams, Holst discovered and became an admirer of the music of Ravel, whom he considered a "model of purity" on the level with Haydn, another Composer he greatly admired.

While in Germany, Holst reappraised his professional life, and in 1903 he decided to abandon orchestral playing to concentrate on composition. His earnings as a Composer were too little to live on, and two years later he accepted the offer of a teaching post at James Allen's Girls' School, Dulwich, which he held until 1921. He also taught at the Passmore Edwards Settlement, where among other innovations he gave the British premieres of two Bach cantatas. The two teaching posts for which he is probably best known were Director of music at St Paul's Girls' School, Hammersmith, from 1905 until his death, and Director of music at Morley College from 1907 to 1924. Vaughan Williams wrote of the former establishment: "Here he did away with the childish sentimentality which schoolgirls were supposed to appreciate and substituted Bach and Vittoria; a splendid background for immature minds." Several of Holst's pupils at St Paul's went on to distinguished careers, including the Soprano Joan Cross, and the oboist and cor anglais player Helen Gaskell. Of Holst's impact on Morley College, Vaughan Williams wrote: "[A] bad tradition had to be broken down. The results were at first discouraging, but soon a new spirit appeared and the music of Morley College, together with its offshoot the 'Whitsuntide festival' ... became a force to be reckoned with". Before Holst's appointment, Morley College had not treated music very seriously (Vaughan Williams's "bad tradition"), and at first Holst's exacting demands drove many students away. He persevered, and gradually built up a class of dedicated music-lovers.

As a Composer Holst was frequently inspired by literature. He set poetry by Thomas Hardy and Robert Bridges and, a particular influence, Walt Whitman, whose words he set in "Dirge for Two Veterans" and The Mystic Trumpeter (1904). He wrote an orchestral Walt Whitman Overture in 1899. While on tour with the Carl Rosa company Holst had read some of Max Müller's books, which inspired in him a keen interest in Sanskrit texts, particularly the Rig Veda hymns. He found the existing English versions of the texts unconvincing, and decided to make his own translations, despite his lack of skills as a Linguist. He enrolled in 1909 at University College, London, to study the language. Imogen commented on his translations: "He was not a poet, and there are occasions when his verses seem naïve. But they never sound vague or slovenly, for he had set himself the task of finding words that would be 'clear and dignified' and that would 'lead the listener into another world'". His settings of translations of Sanskrit texts included Sita (1899–1906), a three-act opera based on an episode in the Ramayana (which he eventually entered for a competition for English opera set by the Milan music publisher Tito Ricordi); Savitri (1908), a chamber opera based on a tale from the Mahabharata; four groups of Hymns from the Rig Veda (1908–14); and two texts originally by Kālidāsa: Two Eastern Pictures (1909–10) and The Cloud Messenger (1913).

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, British musical circles had experienced a new interest in national folk music. Some composers, such as Sullivan and Elgar, remained indifferent, but Parry, Stanford, Stainer and Alexander Mackenzie were founding members of the Folk-Song Society. Parry considered that by recovering English folk song, English composers would find an authentic national voice; he commented, "in true folk-songs there is no sham, no got-up glitter, and no vulgarity". Vaughan Williams was an early and enthusiastic convert to this cause, going round the English countryside collecting and noting down folk songs. These had an influence on Holst. Though not as passionate on the subject as his friend, he incorporated a number of folk melodies in his own compositions and made several arrangements of folk songs collected by others. The Somerset Rhapsody (1906–07), was written at the suggestion of the folk-song collector Cecil Sharp and made use of tunes that Sharp had noted down. Holst described its performance at the Queen's Hall in 1910 as "my first real success". A few years later Holst became excited by another musical renaissance—the rediscovery of English madrigal composers. Weelkes was his favourite of all the Tudor composers, but Byrd also meant much to him.

In the years before the First World War, Holst composed in a variety of genres. Matthews considers the evocation of a North African town in the Beni Mora suite of 1908 the composer's most individual work to that date; the third movement gives a preview of minimalism in its constant repetition of a four-bar theme. Holst wrote two suites for military band, in E flat (1909) and F major (1911) respectively, the first of which became and remains a brass-band staple. This piece, a highly original and substantial musical work, was a signal departure from what Short describes as "the usual transcriptions and operatic selections which pervaded the band repertoire". Also in 1911 he wrote Hecuba's Lament, a setting of Gilbert Murray's translation from Euripides built on a seven-beat refrain designed, says Dickinson, to represent Hecuba's defiance of Divine wrath. In 1912 Holst composed two psalm settings, in which he experimented with plainsong; the same year saw the enduringly popular St Paul's Suite (a "gay but retrogressive" piece according to Dickinson), and the failure of his large scale orchestral work Phantastes.

According to Rubbra, the publication in 1911 of Holst's Rig Veda Hymns was a landmark event in the composer's development: "Before this, Holst's music had, indeed, shown the clarity of utterance which has always been his characteristic, but harmonically there was little to single him out as an important figure in modern music." Dickinson describes these vedic settings as pictorial rather than religious; although the quality is variable the sacred texts clearly "touched vital springs in the composer's imagination". While the music of Holst's Indian verse settings remained generally western in character, in some of the vedic settings he experimented with Indian raga (scales).

Holst conceived the idea of The Planets in 1913, partly as a result of his interest in astrology, and also from his determination, despite the failure of Phantastes, to produce a large-scale orchestral work. The chosen format may have been influenced by Schoenberg's Fünf Orchesterstücke, and shares something of the aesthetic, Matthews suggests, of Debussy's Nocturnes or La mer. Holst began composing The Planets in 1914; the movements appeared not quite in their final sequence; "Mars" was the first to be written, followed by "Venus" and "Jupiter". "Saturn", "Uranus" and "Neptune" were all composed during 1915, and "Mercury" was completed in 1916.

During and after the composition of The Planets, Holst wrote or arranged numerous vocal and choral works, many of them for the wartime Thaxted Whitsun Festivals, 1916–18. They include the Six Choral Folksongs of 1916, based on West Country tunes, of which "Swansea Town", with its "sophisticated tone", is deemed by Dickinson to be the most memorable. Holst downplayed such music as "a limited form of art" in which "mannerisms are almost inevitable"; the Composer Alan Gibbs, however, believes Holst's set at least equal to Vaughan Williams's Five English Folk Songs of 1913.

Holst's first major work after The Planets was the Hymn of Jesus, completed in 1917. The words are from a Gnostic text, the apocryphal Acts of St John, using a translation from the Greek which Holst prepared with assistance from Clifford Bax and Jane Joseph. Head comments on the innovative character of the Hymn: "At a stroke Holst had cast aside the Victorian and Edwardian sentimental oratorio, and created the precursor of the kind of works that John Tavener, for Example, was to write in the 1970s". Matthews has written that the Hymn's "ecstatic" quality is matched in English music "perhaps only by Tippett's The Vision of Saint Augustine"; the musical elements include plainsong, two choirs distanced from each other to emphasise dialogue, dance episodes and "explosive chordal dislocations".

In the Ode to Death (1918–19), the quiet, resigned mood is seen by Matthews as an "abrupt volte-face" after the life-enhancing spirituality of the Hymn. Warrack refers to its aloof tranquillity; Imogen Holst believed the Ode expressed Holst's private attitude to death. The piece has rarely been performed since its premiere in 1922, although the Composer Ernest Walker thought it was Holst's finest work to that date.

Holst enjoyed his time in Salonica, from where he was able to visit Athens, which greatly impressed him. His musical duties were wide-ranging, and even obliged him on occasion to play the violin in the local orchestra: "it was great fun, but I fear I was not of much use". He returned to England in June 1919.

Holst, in his forties, suddenly found himself in demand. The New York Philharmonic and Chicago Symphony Orchestra vied to be the first to play The Planets in the US. The success of that work was followed in 1920 by an enthusiastic reception for The Hymn of Jesus, described in The Observer as "one of the most brilliant and one of the most sincere pieces of choral and orchestral expression heard for some years." The Times called it "undoubtedly the most strikingly original choral work which has been produced in this country for many years."

Holst made some recordings, conducting his own music. For the Columbia company he recorded Beni Mora, the Marching Song and the complete Planets with the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) in 1922, using the acoustic process. The limitations of early recording prevented the gradual fade-out of women's voices at the end of "Neptune", and the lower strings had to be replaced by a tuba to obtain an effective bass sound. With an anonymous string orchestra Holst recorded the St Paul's Suite and Country Song in 1925. Columbia's main rival, HMV, issued recordings of some of the same repertoire, with an unnamed orchestra conducted by Albert Coates. When electrical recording came in, with dramatically improved recording quality, Holst and the LSO re-recorded The Planets for Columbia in 1926.

Holst's comic opera The Perfect Fool (1923) was widely seen as a satire of Parsifal, though Holst firmly denied it. The piece, with Maggie Teyte in the leading Soprano role and Eugene Goossens conducting, was enthusiastically received at its premiere in the Royal Opera House. At a concert in Reading in 1923, Holst slipped and fell, suffering concussion. He seemed to make a good recovery, and he felt up to accepting an invitation to the US, lecturing and conducting at the University of Michigan. After he returned he found himself more and more in demand, to conduct, prepare his earlier works for publication, and, as before, to teach. The strain caused by these demands on him was too great; on doctor's orders he cancelled all professional engagements during 1924, and retreated to Thaxted. In 1925 he resumed his work at St Paul's Girls' School, but did not return to any of his other posts.

Before his enforced rest in 1924, Holst demonstrated a new interest in counterpoint, in his Fugal Overture of 1922 for full orchestra and the neo-classical Fugal Concerto of 1923, for flute, oboe and strings. In his final decade he mixed song settings and minor pieces with major works and occasional new departures; the 1925 Terzetto for flute, violin and oboe, each instrument playing in a different key, is cited by Imogen as Holst's only successful chamber work. Of the Choral Symphony completed in 1924, Matthews writes that, after several movements of real quality, the finale is a rambling anticlimax. Holst's penultimate opera, At the Boar's Head (1924), is based on tavern scenes from Shakespeare's Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2. The music, which is largely derived from old English melodies gleaned from Cecil Sharp and other collections, has pace and verve; the contemporary critic Harvey Grace discounted the lack of originality, a facet which he said "can be shown no less convincingly by a composer's handling of material than by its invention".

Egdon Heath (1927) was Holst's first major orchestral work after The Planets. Matthews summarises the music as "elusive and unpredictable [with] three main elements: a pulseless wandering melody [for strings], a sad brass processional, and restless music for strings and oboe." The mysterious dance towards the end is, says Matthews, "the strangest moment in a strange work". Richard Greene in Music & Letters describes the piece as "a larghetto dance in a siciliano rhythm with a simple, stepwise, rocking melody", but lacking the power of The Planets and, at times, monotonous to the listener. A more popular success was the Moorside Suite for brass band, written as a test piece for the National Brass Band Festival championships of 1928. While written within the traditions of north-country brass-band music, the suite, Short says, bears Holst's unmistakable imprint, "from the skipping 6/8 of the opening Scherzo, to the vigorous melodic fourths of the concluding March, the intervening Nocturne bearing a family resemblance to the slow-moving procession of Saturn". 'A Moorside Suite' has undergone major revisionism in the article 'Symphony Within: rehearing Holst's 'A Moorside Suite' by Stephen Arthur Allen in the Winter 2017 edition of 'The Musical Times'. As with 'Egdon Heath' – commissioned as a symphony – the article reveals the symphonic nature of this brass-band work.

Holst's productivity as a Composer benefited almost at once from his release from other work. His works from this period include the Choral Symphony to words by Keats (a Second Choral Symphony to words by George Meredith exists only in fragments). A short Shakespearian opera, At the Boar's Head, followed; neither had the immediate popular appeal of A Moorside Suite for brass band of 1928.

After this, Holst tackled his final attempt at opera in a cheerful vein, with The Wandering Scholar (1929–30), to a text by Clifford Bax. Imogen refers to the music as "Holst at his best in a scherzando (playful) frame of mind"; Vaughan Williams commented on the lively, folksy rhythms: "Do you think there's a little bit too much 6/8 in the opera?" Short observes that the opening motif makes several reappearances without being identified with a particular character, but imposes musical unity on the work.

Holst composed few large-scale works in his final years. A Choral Fantasia of 1930 was written for the Three Choirs Festival at Gloucester; beginning and ending with a Soprano soloist, the work, also involving chorus, strings, brass and percussion, includes a substantial organ solo which, says Imogen Holst, "knows something of the 'colossal and mysterious' loneliness of Egdon Heath". Apart from his final uncompleted symphony, Holst's remaining works were for small forces; the eight Canons of 1932 were dedicated to his pupils, though in Imogen's view that they present a formidable challenge to the most professional of Singers. The Brook Green Suite (1932), written for the orchestra of St Paul's School, was a late companion piece to the St Paul's Suite. The Lyric Movement for viola and small orchestra (1933) was written for Lionel Tertis. Quiet and contemplative, and requiring little virtuosity from the soloist, the piece was slow to gain popularity among violists. Robin Hull, in Penguin Music Magazine, praised the work's "clear beauty—impossible to mistake for the art of any other composer"; in Dickinson's view, however, it remains "a frail creation". Holst's final composition, the orchestral scherzo movement of a projected symphony, contains features characteristic of much of Holst's earlier music—"a summing up of Holst's orchestral art", according to Short. Dickinson suggests that the somewhat Casual collection of material in the work gives little indication of the symphony that might have been written.

Holst wrote a score for a British film, The Bells (1931), and was amused to be recruited as an extra in a crowd scene. Both film and score are now lost. He wrote a "jazz band piece" that Imogen later arranged for orchestra as Capriccio. Having composed operas throughout his life with varying success, Holst found for his last opera, The Wandering Scholar, what Matthews calls "the right medium for his oblique sense of humour, writing with economy and directness".

Harvard University offered Holst a lectureship for the first six months of 1932. Arriving via New York he was pleased to be reunited with his brother, Emil, whose acting career under the name of Ernest Cossart had taken him to Broadway; but Holst was dismayed by the continual attentions of press interviewers and Photographers. He enjoyed his time at Harvard, but was taken ill while there: a duodenal ulcer prostrated him for some weeks. He returned to England, joined briefly by his brother for a holiday together in the Cotswolds. His health declined, and he withdrew further from musical activities. One of his last efforts was to guide the young players of the St Paul's Girls' School orchestra through one of his final compositions, the Brook Green Suite, in March 1934.

Holst died in London on 25 May 1934, at the age of 59, of heart failure following an operation on his ulcer. His ashes were interred at Chichester Cathedral in Sussex, close to the memorial to Thomas Weelkes, his favourite Tudor Composer. Bishop George Bell gave the memorial oration at the funeral, and Vaughan Williams conducted music by Holst and himself.

In the early LP era little of Holst's music was available on disc. Only six of his works are listed in the 1955 issue of The Record Guide: The Planets (recordings under Boult on HMV and Nixa, and another under Sir Malcolm Sargent on Decca); the Perfect Fool ballet music; the St Paul's Suite; and three short choral pieces. In the stereo LP and CD eras numerous recordings of The Planets were issued, performed by orchestras and conductors from round the world. By the early years of the 21st century most of the major and many of the minor orchestral and choral works had been issued on disc. The 2008 issue of The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music contained seven pages of listings of Holst's works on CD. Of the operas, Savitri, The Wandering Scholar, and At the Boar's Head have been recorded.

Holst's works were played frequently in the early years of the 20th century, but it was not until the international success of The Planets in the years immediately after the First World War that he became a well-known figure. A shy man, he did not welcome this fame, and preferred to be left in peace to compose and teach. In his later years his uncompromising, personal style of composition struck many music lovers as too austere, and his brief popularity declined. Nevertheless, he was a significant influence on a number of younger English composers, including Edmund Rubbra, Michael Tippett and Benjamin Britten. Apart from The Planets and a handful of other works, his music was generally neglected until the 1980s, when recordings of much of his output became available.

On 27 September 2009, after a weekend of concerts at Chichester Cathedral in memory of Holst, a new memorial was unveiled to mark the 75th anniversary of the composer's death. It is inscribed with words from the text of The Hymn of Jesus: "The heavenly spheres make music for us". In April 2011 a BBC television documentary, Holst: In the Bleak Midwinter, charted Holst's life with particular reference to his support for socialism and the cause of working people.

Short cites other English composers who are in debt to Holst, in particular william Walton and Benjamin Britten, and suggests that Holst's influence may have been felt further afield. Above all, Short recognises Holst as a Composer for the people, who believed it was a composer's duty to provide music for practical purposes—festivals, celebrations, ceremonies, Christmas carols or simple hymn tunes. Thus, says Short, "many people who may never have heard any of [Holst's] major works ... have nevertheless derived great pleasure from hearing or singing such small masterpieces as the carol 'In the Bleak Midwinter'".