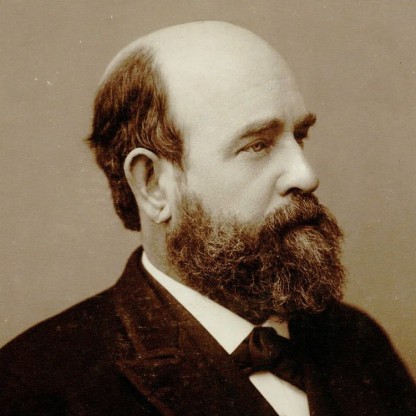

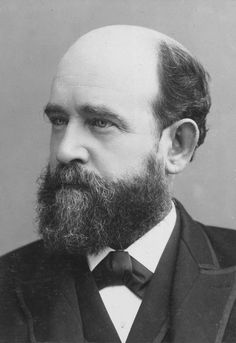

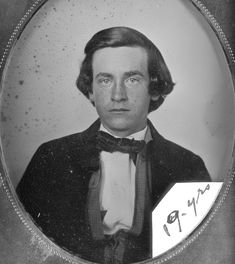

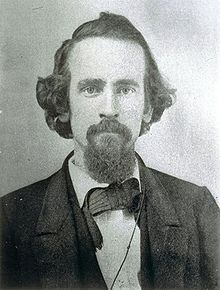

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Economist, Politician, Writer |

| Birth Day | September 02, 1839 |

| Birth Place | Philadelphia, United States |

| Age | 180 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | October 29, 1897(1897-10-29) (aged 58)\nNew York City, New York, US |

| Birth Sign | Libra |

| Cause of death | Stroke |

| Education | Primary |

| Spouse(s) | Annie Corsina Fox |

| School | Georgism |

| Main interests | Classical economics, ethics, political and economic philosophy, socialism, laissez-faire, history, free trade, land economics |

| Notable ideas | Unearned income, land value tax, municipalization, free public goods from land value capture, single-tax, intellectual property reform, citizen's dividend, monetary sovereignty, the role of monopoly/privilege/land in effecting economic inequality and the business cycle |

Net worth: $9 Million (2024)

Henry George, a renowned economist, politician, and writer in the United States, is estimated to have a net worth of $9 million in 2024. Known for his influential contributions to economics and political theory, George was a proponent of the single-tax system and his ideas on land value capture and public revenue generated significant interest and debate. Through his influential book, "Progress and Poverty," George sought to address the social inequalities arising from the unrestrained accumulation of wealth and became a prominent figure in the Progressive Era. Despite his untimely death in 1897, Henry George's ideas continue to shape economic discourse and his estimated net worth in 2024 reflects not only his intellectual influence but possibly also the enduring relevance of his work.

Famous Quotes:

I asked a passing teamster, for want of something better to say, what land was worth there. He pointed to some cows grazing so far off that they looked like mice, and said, "I don't know exactly, but there is a man over there who will sell some land for a thousand dollars an acre." Like a flash it came over me that there was the reason of advancing poverty with advancing wealth. With the growth of population, land grows in value, and the men who work it must pay more for the privilege.

Biography/Timeline

George was born in Philadelphia to a lower-middle-class family, the second of ten children of Richard S. H. George and Catharine Pratt George (née Vallance). His father was a publisher of religious texts and a devout Episcopalian, and sent George to the Episcopal Academy in Philadelphia. George chafed at his religious upbringing and left the academy without graduating. Instead he convinced his father to hire a tutor and supplemented this with avid reading and attending lectures at the Franklin institute. His formal education ended at age 14 and he went to sea as a foremast boy at age 15 in April 1855 on the Hindoo, bound for Melbourne and Calcutta. He ended up in the American West in 1858 and briefly considered prospecting for gold but instead started work the same year in San Francisco as a type setter.

In California, George fell in love with Annie Corsina Fox, an eighteen-year-old girl from Sydney who had been orphaned and was living with an uncle. The uncle, a prosperous, strong-minded man, was opposed to his niece's impoverished suitor. But the couple, defying him, eloped and married in late 1861, with Henry dressed in a borrowed suit and Annie bringing only a packet of books. The marriage was a happy one and four children were born to them. On November 3, 1862 Annie gave birth to Future United States Representative from New York, Henry George, Jr. (1862–1916). Early on, even with the birth of Future Sculptor Richard F. George (1865 – September 28, 1912), the family was near starvation.

George's other two children were both daughters. The first was Jennie George, (c. 1867–1897), later to become Jennie George Atkinson. George's other daughter was Anna Angela George (b. 1879), who would become mother of both Future Dancer and Choreographer, Agnes de Mille and Future Actress Peggy George, who was born Margaret George de Mille.

George began as a Lincoln Republican, but then became a Democrat. He was a strong critic of railroad and mining interests, corrupt politicians, land speculators, and labor contractors. He first articulated his views in an 1868 article entitled "What the Railroad Will Bring Us." George argued that the boom in railroad construction would benefit only the lucky few who owned interests in the railroads and other related enterprises, while throwing the greater part of the population into abject poverty. This had led to him earning the enmity of the Central Pacific Railroad's executives, who helped defeat his bid for election to the California State Assembly.

George was one of the earliest and most prominent advocates for adoption of the secret ballot in the United States. Harvard Historian Jill Lepore asserts that Henry George's advocacy is the reason Americans vote with secret ballots today. George's first article in support of the secret ballot was entitled "Bribery in Elections" and was published in the Overland Review of December 1871. His second article was "Money in Elections," published in the North American Review of March 1883. The first secret ballot reform approved by a state legislature was brought about by reformers who said they were influenced by George. The first state to adopt the secret ballot, also called The Australian Ballot, was Massachusetts in 1888 under the leadership of Richard Henry Dana III. By 1891, more than half the states had adopted it too.

Furthermore, on a visit to New York City, he was struck by the apparent paradox that the poor in that long-established city were much worse off than the poor in less developed California. These observations supplied the theme and title for his 1879 book Progress and Poverty, which was a great success, selling over 3 million copies. In it George made the argument that a sizeable portion of the wealth created by social and technological advances in a free market economy is possessed by land owners and monopolists via economic rents, and that this concentration of unearned wealth is the main cause of poverty. George considered it a great injustice that private profit was being earned from restricting access to natural resources while productive activity was burdened with heavy taxes, and indicated that such a system was equivalent to slavery—a concept somewhat similar to wage slavery. This is also the work in which he made the case for a land value tax in which governments would tax the value of the land itself, thus preventing private interests from profiting upon its mere possession, but allowing the value of all improvements made to that land to remain with Investors.

In 1880, now a popular Writer and speaker, George moved to New York City, becoming closely allied with the Irish nationalist community despite being of English ancestry. From there he made several speaking journeys abroad to places such as Ireland and Scotland where access to land was (and still is) a major political issue.

In 1886, George campaigned for mayor of New York City as the candidate of the United Labor Party, the short-lived political society of the Central Labor Union. He polled second, more than the Republican candidate Theodore Roosevelt. The election was won by Tammany Hall candidate Abram Stevens Hewitt by what many of George's supporters believed was fraud. In the 1887 New York state elections, George came in a distant third in the election for Secretary of State of New York. The United Labor Party was soon weakened by internal divisions: the management was essentially Georgist, but as a party of organized labor it also included some Marxist members who did not want to distinguish between land and capital, many Catholic members who were discouraged by the excommunication of Father Edward McGlynn, and many who disagreed with George's free trade policy. George had particular trouble with Terrence V. Powderly, President of the Knights of Labor, a key member of the United Labor coalition. While initially friendly with Powderly, George vigorously opposed the tariff policies which Powderly and many other labor Leaders thought vital to the protection of American workers. George's strident criticism of the tariff set him against Powderly and others in the labor movement.

Joseph Jay "J.J." Pastoriza led a successful Georgist movement in Houston. Though the Georgist club, the Houston Single Tax League, started there in 1890, Pastoriza lent use of his property to the league in 1903. He retired from the printing Business in 1906 in order to dedicate his life to public Service, then traveled the United States and Europe while studying various systems of taxing property. He returned to Houston and served as Houston Tax Commissioner from 1911 through 1917. He introduced his "Houston Plan of Taxation" in 1912: improvements to land and merchants' inventories were taxed at 25 percent of appraised value, unimproved land was taxed at 70 percent of appraisal, and personal property was exempt. However, in 1915, two courts ruled that the Houston Plan violated the Texas Constitution.

A large number of famous individuals, particularly Progressive Era figures, claim inspiration from Henry George's ideas. John Peter Altgeld wrote that George "made almost as great an impression on the economic thought of the age as Darwin did on the world of science." Jose Marti wrote, "Only Darwin in the natural sciences has made a mark comparable to George's on social science." In 1892, Alfred Russel Wallace stated that George's Progress and Poverty was "undoubtedly the most remarkable and important book of the present century," implicitly placing it above even The Origin of Species, which he had earlier helped develop and publicize.

The social scientist and Economist John A. Hobson observed in 1897 that “Henry George may be considered to have exercised a more directly powerful formative and educative influence over English radicalism of the last fifteen years than any other man," and that George "was able to drive an abstract notion, that of economic rent, into the minds of a large number of ‘practical’ men, and so generate therefrom a social movement. George had all the popular gifts of the American orator and Journalist, with something more. Sincerity rang out of every utterance." Many others agree with Hobson. George Bernard Shaw claims that Henry George was responsible for inspiring 5 out of 6 socialist reformers in Britain during the 1880s, who created socialist organizations such as the Fabian Society. The controversial People's Budget and the Land Values (Scotland) Bill were inspired by Henry George and resulted in a constitutional crisis and the Parliament Act 1911 to reform of the House of Lords, which had blocked the land reform. In Denmark, the Danmarks Retsforbund, known in English as the Justice Party or Single-Tax Party, was founded in 1919. The party's platform is based upon the land tax principles of Henry George. The party was elected to parliament for the first time in 1926, and they were moderately successful in the post-war period and managed to join a governing coalition with the Social Democrats and the Social Liberal Party from the years 1957–60, with diminishing success afterwards.

Non-political means have also been attempted to further the cause. A number of "Single Tax Colonies" were started, such as Arden, Delaware and Fairhope, Alabama. In 1904, Lizzie Magie created a board game called The Landlord's Game to demonstrate George's theories. This was later turned into the popular board game Monopoly.

In 1977, Joseph Stiglitz showed that under certain conditions, spending by the government on public goods will increase aggregate land rents by at least an equal amount. This result has been dubbed by economists the Henry George theorem, as it characterizes a situation where Henry George's "single tax" is not only efficient, it is also the only tax necessary to Finance public expenditures.

In 1997, Spencer MacCallum wrote that Henry George was "undeniably the greatest Writer and orator on free trade who ever lived."

In 2009, Tyler Cowen wrote that George's 1886 book Protection or Free Trade "remains perhaps the best-argued tract on free trade to this day."

Another spirited response came from British Biologist T.H. Huxley in his article "Capital – the Mother of Labour," published in 1890 in the journal The Nineteenth Century. Huxley used the scientific principles of Energy to undermine George's theory, arguing that, energetically speaking, labor is unproductive.

Mason Gaffney, an American Economist and a major Georgist critic of neoclassical economics, argued that neoclassical economics was designed and promoted by landowners and their hired economists to divert attention from George's extremely popular philosophy that since land and resources are provided by nature, and their value is given by society, land value—rather than labor or capital—should provide the tax base to fund government and its expenditures.

Before reading Progress and Poverty, Helen Keller was a socialist who believed that Georgism was a good step in the right direction. She later wrote of finding "in Henry George’s philosophy a rare beauty and power of inspiration, and a splendid faith in the essential nobility of human nature." Some speculate that the passion, sincerity, clear explanations evident in Henry George's writing account for the almost religious passion that many believers in George's theories exhibit, and that the promised possibility of creating heaven on Earth filled a spiritual void during an era of secularization. Josiah Wedgwood, the Liberal and later Labour Party Politician wrote that ever since reading Henry George's work, "I have known 'that there was a man from God, and his name was Henry George.' I had no need hence-forth for any other faith."