Age, Biography and Wiki

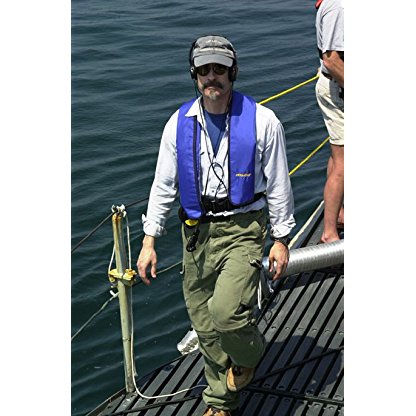

| Who is it? | Writer, Producer, Actor |

| Birth Day | November 07, 1897 |

| Birth Place | New York City, New York, United States |

| Age | 122 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | March 5, 1953(1953-03-05) (aged 55)\nHollywood, California, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Sagittarius |

| Alma mater | Columbia University |

| Occupation | Screenwriter |

| Years active | 1926–1952 |

| Spouse(s) | Sara Aaronson (1897-1985) |

| Children | 3, including Don and Frank |

| Family | See Mankiewicz family |

Net worth

Herman J. Mankiewicz, a highly esteemed individual in the entertainment industry, is recognized for his significant contributions as a writer, producer, and actor in the United States. As a multi-talented individual, Mankiewicz's net worth is estimated to be between $100K and $1M in the year 2024. Throughout his career, he has undoubtedly left a lasting impact on the film industry, crafting compelling stories and playing an instrumental role behind the scenes. With his vast array of talents, Mankiewicz's work continues to inspire and captivate audiences to this day.

Famous Quotes:

God, if I hadn't loved him I would have hated him after all those ridiculous stories, persuading people I was offering him money to have his name taken off...that he would be carrying on like this, denouncing me as a coauthor, screaming around.

Biography/Timeline

Herman Mankiewicz was born in New York City in 1897. His parents were of German Jewish ancestry: his father, Franz Mankiewicz, was born in Berlin and emigrated to the U.S. from Hamburg in 1892. He arrived in the U.S. with his wife, a dressmaker named Johanna Blumenau, who was from the German-speaking Kurland region." The family lived first in New York and then moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where Herman's father accepted a teaching position. In 1909, Herman's brother, Joseph L. Mankiewicz (who himself would have a career as a successful Writer, Producer, and director), was born, and both boys and a sister spent their childhood there. Census records indicate the family lived on Academy Street.

Mankiewicz's younger brother was Joseph L. Mankiewicz (1909–1993), also an Oscar-winning Hollywood Director, Screenwriter, and Producer.

The family moved to New York City in 1913, and Herman graduated from Columbia University in 1917. After a period as managing Editor of the American Jewish Chronicle, he became a flying cadet with the United States Army in 1917, and, in 1918, a private first class with the Marines, A.E.F. In 1919 and 1920, he became Director of the American Red Cross News Service in Paris, and after returning to the U.S. married Sara Aaronson, of Baltimore. He took his bride overseas with him on his next job as a foreign correspondent in Berlin from 1920 to 1922, doing political reporting for George Seldes on the Chicago Tribune.

His children were Screenwriter Don Mankiewicz (1922-2015), Politician Frank Mankiewicz (1924-2014), and Novelist Johanna Mankiewicz Davis (1937-1974).

While a reporter in Berlin for the Chicago Tribune, he also sent pieces on drama and books to The New York Times. At one point, he was hired in Berlin by Dancer Isadora Duncan, to be her publicist in preparation for her return tour in America. At home again in the U.S., he took a job as a reporter for the New York World. He was known as a "gifted, prodigious Writer," and contributed to Vanity Fair, The Saturday Evening Post and numerous other magazines. While still in his twenties, he collaborated with Heywood Broun, Dorothy Parker, Robert E. Sherwood, and others on a revue, and collaborated with George S. Kaufman on a play, The Good Fellow, and with Marc Connelly on The Wild Man of Borneo. From 1923 to 1926, he was at The New York Times backing up George S. Kaufman in the drama department and soon after became the first regular theatre critic for The New Yorker, writing a weekly column during 1925 and 1926. He was a member of the Algonquin Round Table. His writing attracted the notice of film Producer Walter Wanger who offered him a motion-picture contract and he soon moved to Hollywood.

Kael notes that "beginning in 1926, Mankiewicz worked on an astounding number of films." In 1927 and 1928, he did the titles (the printed dialogue and explanations) for at least twenty-five films that starred Clara Bow, Bebe Daniels, Nancy Carroll, Wallace Beery, and other public favorites. By then, sound had come in, and in 1929 he did the script as well as the dialogue for The Dummy, and did the scripts for many Directors, including william Wellman and Josef von Sternberg.

After a month in the movie Business, Mankiewicz signed a year's contract at $400 a week plus bonuses. By the end of 1927, he was head of Paramount's scenario department, and film critic Pauline Kael, who wrote about him and the creation of Citizen Kane in "Raising Kane", her famous 1971 New Yorker article, wrote that "in January, 1928, there was a newspaper item reporting that he was in New York 'lining up a new set of newspaper feature Writers and playwrights to bring to Hollywood,' and that 'most of the newer Writers on Paramount's staff who contributed the most successful stories of the past year' were selected by 'Mank.'" Film Historian Scott Eyman notes that Mankiewicz was put in charge of Writer recruitment by Paramount. However, as "a hard-drinking gambler, he hired men in his own image: Ben Hecht, Bartlett Cormack, Edwin Justus Mayer, Writers comfortable with the iconoclasm of big-city newsrooms who would introduce their sardonic worldliness to movie audiences.

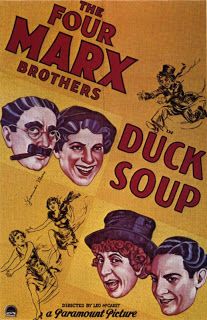

Between 1929 and 1935, he was credited with working on at least twenty films, many of which he received no credit for. Between 1930 and 1932 he was either Producer or associate Producer on four comedies and helped write their screenplays without credit: Laughter, Monkey Business, Horse Feathers, and Million Dollar Legs, which many critics considered one of the funniest comedies of the early 1930s. In 1933, he co-wrote Dinner at Eight, which was based on the George S. Kaufman/Edna Ferber play, and became one of the most popular comedies at that time and remains a "classic" comedy.

Mankiewicz became good friends with Hollywood Screenwriter Charles Lederer, who was Marion Davies's nephew. Lederer grew up as a Hollywood habitué, spending much time at San Simeon, where Davies reigned as william Randolph Hearst's mistress. As one of his admirers in the early 1930s, Hearst often invited Mankiewicz to spend the weekend at San Simeon.

According to The New York Times, in 1935, while he was a staff Writer for MGM, the studio was notified by Dr. Paul Joseph Goebbels, then Minister of Education and Propaganda under Adolf Hitler, that films written by Mankiewicz could not be shown in Nazi Germany unless his name was removed from the screen credits.

In February 1938, he was assigned as the first of ten screenwriters to work on The Wizard of Oz. Three days after he started writing he handed in a seventeen-page treatment of what was later known as "the Kansas sequence". While Baum devoted less than a thousand words in his book to Kansas, Mankiewicz almost balanced the attention on Kansas to the section about Oz. He felt it was necessary to have the audience relate to Dorothy in a real world before transporting her to a magic one. By the end of the week he had finished writing fifty-six pages of the script and included instructions to film the scenes in Kansas in black and white. His goal, according to film Historian Al Jean Harmetz, was to "capture in pictures what Baum had captured in words—the grey lifelessness of Kansas contrasted with the visual richness of Oz." He was not credited for his work on the film, however.

In 1939, Mankiewicz suffered a broken leg in a driving accident and had to be hospitalized. During his hospital stay, one of his visitors was Orson Welles, who met him earlier and had become a great admirer of his wit. During the months after his release from the hospital, he and Welles began working on story ideas which led to the creation of Citizen Kane.

Mankiewicz biographer Richard Meryman notes that the dispute had various causes, including the way the movie was promoted. When RKO opened the movie on Broadway on May 1, 1941, followed by showings at theaters in other large cities, the publicity programs that were printed included photographs of Welles as "the one-man band, directing, acting, and writing." In a letter to his father afterwards, Mankiewicz wrote, "I'm particularly furious at the incredibly insolent description of how Orson wrote his masterpiece. The fact is that there isn't one single line in the picture that wasn't in writing—writing from and by me—before ever a camera turned."

Mankiewicz was an alcoholic, once famously reassuring his hostess at a formal dinner, after he had vomited on her white tablecloth, not to be concerned because "the white wine came up with the fish." He died March 5, 1953, (The same day Joseph Stalin died) of uremic poisoning, at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Los Angeles.

Mankiewicz is best known for his collaboration with Orson Welles on the screenplay of Citizen Kane, for which they both won an Academy Award and later became a source of controversy over who wrote what. Pauline Kael attributed Kane's screenplay to Mankiewicz in a 1971 essay that was strongly disputed and is now discredited. Much debate has centered around this issue, largely because of the importance of the film itself, which most agree is a fictionalized biography of newspaper publisher william Randolph Hearst. According to film biographer David Thomson, however, "No one can now deny Herman Mankiewicz credit for the germ, shape, and pointed language of the screenplay..."

Despite Welles' denial that the film was about Hearst, few people were convinced—including Hearst. After the release of Citizen Kane, Hearst pursued a longtime vendetta against Mankiewicz and Welles for writing the story. "Certain elements in the film were taken from Mankiewicz's own experience: the sled Rosebud was based—according to some sources—on a very important bicycle that was stolen from him....[and] some of Kane's speeches are almost verbatim copies of Hearst's." Most personally, the word "rosebud" was reportedly Hearst's private nickname for Davies' clitoris. Hearst's thoughts about the film are unknown; what is certain is that his extensive chain of newspapers and radio stations blocked all mentions of the film, and refused to accept advertising for it, while some Hearst employees worked behind the scenes to block or restrict its distribution.