Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Explorer |

| Birth Day | February 25, 1304 |

| Birth Place | Tangier, Moroccan |

| Age | 715 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 1369 (aged 64–65)\nMarinid Morocco |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Native name | أبو عبد الله محمد بن عبد الله اللواتي الطنجي بن بطوطة |

| Occupation | Geographer, explorer |

| Era | Medieval era |

Net worth

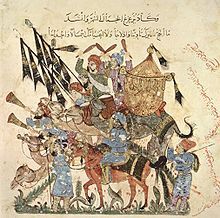

Ibn Battuta, a prominent Moroccan explorer, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million by 2024. Known for his extensive travels across the Muslim world during the 14th century, Ibn Battuta left behind a remarkable legacy. With his insatiable curiosity and thirst for discovery, he embarked on expeditions that covered over 75,000 miles, visiting various countries and regions. His accounts of his journeys have provided valuable insights into the cultures, customs, and history of the places he explored. As a result, Ibn Battuta's contributions to the world of exploration have made him an iconic figure in Moroccan history.

Famous Quotes:

I set out alone, having neither fellow-traveller in whose companionship I might find cheer, nor caravan whose part I might join, but swayed by an overmastering impulse within me and a desire long-cherished in my bosom to visit these illustrious sanctuaries. So I braced my resolution to quit my dear ones, female and male, and forsook my home as birds forsake their nests. My parents being yet in the bonds of life, it weighed sorely upon me to part from them, and both they and I were afflicted with sorrow at this separation.

Biography/Timeline

Ibn Battuta's work was unknown outside the Muslim world until the beginning of the 19th century, when the German traveller-explorer Ulrich Jasper Seetzen (1767–1811) acquired a collection of manuscripts in the Middle East, among which was a 94-page volume containing an abridged version of Ibn Juzayy's text. Three extracts were published in 1818 by the German orientalist Johann Kosegarten. A fourth extract was published the following year. French scholars were alerted to the initial publication by a lengthy review published in the Journal de Savants by the orientalist Silvestre de Sacy.

Three copies of another abridged manuscript were acquired by the Swiss traveller Johann Burckhardt and bequeathed to the University of Cambridge. He gave a brief overview of their content in a book published posthumously in 1819. The Arabic text was translated into English by the orientalist Samuel Lee and published in London in 1829.

In the 1830s, during the French occupation of Algeria, the Bibliothèque Nationale (BNF) in Paris acquired five manuscripts of Ibn Battuta's travels, in which two were complete. One manuscript containing just the second part of the work is dated 1356 and is believed to be Ibn Juzayy's autograph. The BNF manuscripts were used in 1843 by the Irish-French orientalist Baron de Slane to produce a translation into French of Ibn Battuta's visit to the Sudan. They were also studied by the French scholars Charles Defrémery and Beniamino Sanguinetti. Beginning in 1853 they published a series of four volumes containing a critical edition of the Arabic text together with a translation into French. In their introduction Defrémery and Sanguinetti praised Lee's annotations but were critical of his translation which they claimed lacked precision, even in straightforward passages.

In 1929, exactly a century after the publication of Lee's translation, the Historian and orientalist Hamilton Gibb published an English translation of selected portions of Defrémery and Sanguinetti's Arabic text. Gibb had proposed to the Hakluyt Society in 1922 that he should prepare an annotated translation of the entire Rihla into English. His intention was to divide the translated text into four volumes, each volume corresponding to one of the volumes published by Defrémery and Sanguinetti. The first volume was not published until 1958. Gibb died in 1971, having completed the first three volumes. The fourth volume was prepared by Charles Beckingham and published in 1994. Defrémery and Sanguinetti's printed text has now been translated into number of other languages.

Scholars do not believe that Ibn Battuta visited all the places he described and argue that in order to provide a comprehensive description of places in the Muslim world, he relied on hearsay evidence and made use of accounts by earlier travellers. For Example, it is considered very unlikely that Ibn Battuta made a trip up the Volga River from New Sarai to visit Bolghar and there are serious doubts about a number of other journeys such as his trip to Sana'a in Yemen, his journey from Balkh to Bistam in Khorasan and his trip around Anatolia. Ibn Battuta's claim that a Maghrebian called "Abu'l Barakat the Berber" converted the Maldives to Islam is contradicted by an entirely different story which says that the Maldives were converted to Islam after miracles were performed by a Tabrizi named Maulana Shaikh Yusuf Shams-ud-din according to the Tarikh, the official history of the Maldives. Some scholars have also questioned whether he really visited China. Ibn Battuta may have plagiarized entire sections of his descriptions of China lifted from works by other authors like "Masalik al-absar fi mamalik al-amsar" by Shihab al-Umari, Sulaiman al-Tajir, and possibly from Al Juwayni, Rashid al din and an Alexander romance and Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo's writings share extremely sections and themes, and some of the same commentary, it is also unlikely that the 3rd Caliph Uthman ibn Affan had someone with the exact identical name in China who was encountered by Ibn Battuta. However, even if the Rihla is not fully based on what its author personally witnessed, it provides an important account of much of the 14th-century world. Sex slaves were used by Ibn Battuta such as in Delhi. He wedded and divorced women and had children to sex slaves in Malabar, Delhi, and Bukhara. Ibn Battuta insulted Greeks as "enemies of Allah", drunkards and "swine eaters", while at the same time in Ephesus he purchased and used a Greek girl who was one of his many slave girls in his "harem" through Byzantium, Khorasan, African, and Palestine. It was two decades before he again returned to find out what happened to one of his wives and child in Damascus.

There is no indication that Ibn Battuta made any notes or had any journal during his twenty-nine years of travelling. When he came to dictate an account of his experiences he had to rely on memory and manuscripts produced by earlier travellers. Ibn Juzayy did not acknowledge his sources and presented some of the earlier descriptions as Ibn Battuta's own observations. When describing Damascus, Mecca, Medina and some other places in the Middle East, he clearly copied passages from the account by the Andalusian Ibn Jubayr which had been written more than 150 years earlier. Similarly, most of Ibn Juzayy's descriptions of places in Palestine were copied from an account by the 13th-century traveller Muhammad al-Abdari.