Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Civil Engineer |

| Birth Day | April 09, 1806 |

| Birth Place | Portsmouth, England, British |

| Age | 213 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 15 September 1859(1859-09-15) (aged 53)\nWestminster, London, England |

| Birth Sign | Taurus |

| Education | Lycée Henri-IV University of Caen |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Elizabeth Horsley |

| Children | Isambard Brunel Junior Henry Marc Brunel Florence Mary Brunel |

| Parent(s) | Marc Isambard Brunel Sophia Kingdom |

| Discipline | Civil engineer Structural engineer |

| Institutions | Institution of Civil Engineers |

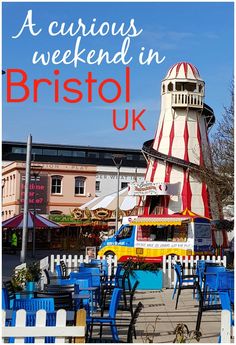

| Projects | Great Western Railway Clifton Suspension Bridge Great Britain |

| Significant design | Royal Albert Bridge |

Net worth

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the renowned British civil engineer, was an illustrious figure of the 19th century, whose net worth is estimated to be between $100,000 and $1 million in the year 2024. Brunel rose to prominence for his remarkable contributions in the field of engineering, revolutionizing the landscape of modern infrastructure. He spearheaded several groundbreaking projects, including the construction of the Thames Tunnel and the magnificent SS Great Eastern. A visionary engineer, Brunel's legacy is still celebrated and his work serves as an inspiration for aspiring engineers across the globe.

Biography/Timeline

The son of French civil Engineer Sir Marc Isambard Brunel and an English mother Sophia Kingdom, Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born on 9 April 1806 in Britain Street, Portsea, Portsmouth, Hampshire, where his Father was working on block-making machinery. He had two older sisters, Sophia (oldest child, Sophia) and Emma, and the whole family moved to London in 1808 for his father's work. Brunel had a happy childhood, despite the family's constant money worries, with his Father acting as his Teacher during his early years. His Father taught him drawing and observational techniques from the age of four and Brunel had learned Euclidean geometry by eight. During this time he also learned fluent French and the basic principles of engineering. He was encouraged to draw interesting buildings and identify any faults in their structure.

When Brunel was 15, his Father Marc, who had accumulated debts of over £5,000, was sent to a debtors' prison. After three months went by with no prospect of release, Marc let it be known that he was considering an offer from the Tsar of Russia. In August 1821, facing the prospect of losing a prominent Engineer, the government relented and issued Marc £5,000 to clear his debts in exchange for his promise to remain in Britain.

When Brunel completed his studies at Henri-IV in 1822, his Father had him presented as a candidate at the renowned engineering school École Polytechnique, but as a foreigner he was deemed ineligible for entry. Brunel subsequently studied under the prominent master clockmaker and horologist Abraham-Louis Breguet, who praised Brunel's potential in letters to his Father. In late 1822, having completed his apprenticeship, Brunel returned to England.

The composition of the riverbed at Rotherhithe was often little more than waterlogged sediment and loose gravel. An ingenious tunnelling shield designed by Marc Brunel helped protect workers from cave-ins, but two incidents of severe flooding halted work for long periods, killing several workers and badly injuring the younger Brunel. The latter incident, in 1828, killed the two most senior miners, and Brunel himself narrowly escaped death. He was seriously injured, and spent six months recuperating. The event stopped work on the tunnel for several years.

In 1830, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Work on the Clifton bridge started in 1831, but was suspended due to the Queen Square riots caused by the arrival of Sir Charles Wetherell in Clifton. The riots drove away Investors, leaving no money for the project, and construction ceased.

In 1833, before the Thames Tunnel was complete, Brunel was appointed chief Engineer of the Great Western Railway, one of the wonders of Victorian Britain, running from London to Bristol and later Exeter. The company was founded at a public meeting in Bristol in 1833, and was incorporated by Act of Parliament in 1835. It was Brunel's vision that passengers would be able to purchase one ticket at London Paddington and travel from London to New York, changing from the Great Western Railway to the Great Western steamship at the terminus in Neyland, West Wales. He surveyed the entire length of the route between London and Bristol himself, with the help of many including his Solicitor Jeremiah Osborne of Bristol Law Firm Osborne Clarke who on one occasion rowed Brunel down the River Avon himself to survey the bank of the river for the route.

Though the Thames Tunnel was eventually completed during Marc Brunel's lifetime, his son had no further involvement with the tunnel proper, only using the abandoned works at Rotherhithe to further his abortive Gaz experiments. This was based on an idea of his father's, and was intended to develop into an engine that ran on power generated from alternately heating and cooling carbon dioxide made from ammonium carbonate and sulphuric acid. Despite interest from several parties (the Admiralty included) the experiments were judged by Brunel to be a failure on the grounds of fuel economy alone, and were discontinued after 1834.

In 1835, before the Great Western Railway had opened, Brunel proposed extending its transport network by boat from Bristol across the Atlantic Ocean to New York City. The Great Western Steamship Company was formed by Thomas Guppy for that purpose. It was widely disputed whether it would be commercially viable for a ship powered purely by steam to make such long journeys. Technological developments in the early 1830s—including the invention of the surface condenser, which allowed boilers to run on salt water without stopping to be cleaned—made longer journeys more possible, but it was generally thought that a ship would not be able to carry enough fuel for the trip and have room for a commercial cargo. Brunel applied the experimental evidence of Beaufoyand further developed the theory that the amount a ship could carry increased as the cube of its dimensions, whereas the amount of resistance a ship experienced from the water as it travelled only increased by a square of its dimensions. This would mean that moving a larger ship would take proportionately less fuel than a smaller ship. To test this theory, Brunel offered his services for free to the Great Western Steamship Company, which appointed him to its building committee and entrusted him with designing its first ship, the Great Western.

When it was built, the Great Western was the longest ship in the world at 236 ft (72 m) with a 250-foot (76 m) keel. The ship was constructed mainly from wood, but Brunel added bolts and iron diagonal reinforcements to maintain the keel's strength. In addition to its steam-powered paddle wheels, the ship carried four masts for sails. The Great Western embarked on her maiden voyage from Avonmouth, Bristol, to New York on 8 April 1838 with 600 long tons (610,000 kg) of coal, cargo and seven passengers on board. Brunel himself missed this initial crossing, having been injured during a fire aboard the ship as she was returning from fitting out in London. As the fire delayed the launch several days, the Great Western missed its opportunity to claim title as the first ship to cross the Atlantic under steam power alone. Even with a four-day head start, the competing Sirius arrived only one day earlier and its crew was forced to burn cabin furniture, spare yards and one mast for fuel. In contrast, the Great Western crossing of the Atlantic took 15 days and five hours, and the ship arrived at her destination with a third of its coal still remaining, demonstrating that Brunel's calculations were correct. The Great Western had proved the viability of commercial transatlantic steamship Service, which led the Great Western Steamboat Company to use her in regular Service between Bristol and New York from 1838 to 1846. She made 64 crossings, and was the first ship to hold the Blue Riband with a crossing time of 13 days westbound and 12 days 6 hours eastbound. The Service was commercially successful enough for a sister ship to be required, which Brunel was asked to design.

In 1843, while performing a conjuring trick for the amusement of his children, Brunel accidentally inhaled a half-sovereign coin, which became lodged in his windpipe. A special pair of forceps failed to remove it, as did a machine devised by Brunel to shake it loose. At the suggestion of his Father, Brunel was strapped to a board and turned upside-down, and the coin was jerked free. He recuperated at Teignmouth, and enjoyed the area so much that he purchased an estate at Watcombe in Torquay, Devon. Here he commissioned william Burn to design Brunel Manor and its gardens to be his country home. He never saw the house or gardens finished, as he died before it was completed.

In May 1845 Hungerford Bridge, a suspension footbridge across the Thames near Charing Cross Station in London, was opened. Its central span was 676.5 ft, and its cost was £106,000. It was replaced by a new railway bridge in 1859, and the suspension chains were used to complete the Clifton Suspension Bridge.

The system never managed to prove itself. The accounts of the SDR for 1848 suggest that atmospheric traction cost 3s 1d (three shillings and one penny) per mile compared to 1s 4d/mile for conventional steam power (because of the many operating issues associated with the atmospheric, few of which were solved during its working life, the actual cost efficiency proved impossible to calculate). A number of South Devon Railway engine houses still stand, including that at Totnes (scheduled as a grade II listed monument in 2007 to prevent its imminent demolition, even as Brunel's bicentenary celebrations were continuing) and at Starcross, on the estuary of the River Exe, which is a striking landmark, and a reminder of the atmospheric railway, also commemorated as the name of the village pub.

In 1852 Brunel turned to a third ship, larger than her predecessors, intended for voyages to India and Australia. The Great Eastern (originally dubbed Leviathan) was cutting-edge Technology for her time: almost 700 ft (210 m) long, fitted out with the most luxurious appointments, and capable of carrying over 4,000 passengers. Great Eastern was designed to cruise non-stop from London to Sydney and back (since Engineers of the time mistakenly believed that Australia had no coal reserves), and she remained the largest ship built until the start of the 20th century. Like many of Brunel's ambitious projects, the ship soon ran over budget and behind schedule in the face of a series of technical problems. The ship has been portrayed as a white elephant, but it has been argued by David P. Billington that in this case Brunel's failure was principally one of economics—his ships were simply years ahead of their time. His vision and engineering innovations made the building of large-scale, propeller-driven, all-metal steamships a practical reality, but the prevailing economic and industrial conditions meant that it would be several decades before transoceanic steamship travel emerged as a viable industry.

During 1854 Britain entered into the Crimean War, and an old Turkish barracks became the British Army Hospital in Scutari. Injured men contracted a variety of illnesses—including cholera, dysentery, typhoid and malaria—due to poor conditions there, and Florence Nightingale sent a plea to The Times for the government to produce a solution.

Brunel was working on the Great Eastern amongst other projects, but accepted the task in February 1855 of designing and building the War Office requirement of a temporary, pre-fabricated hospital that could be shipped to Crimea and erected there. In 5 months the team he had assembled designed, built, and shipped pre-fabricated wood and canvas buildings, providing them complete with advice on transportation and positioning of the facilities.

Brunel's last major undertaking was the unique Three Bridges, London. Work began in 1856, and was completed in 1859.

For the 100th anniversary of the Royal Albert Bridge, the words "I.K. BRUNEL Engineer 1859" were engraved on either end to commemorate his enduring legacy. The words had become obscured by paint, but were restored by Network Rail and revealed again in 2006.

Great Eastern was built at John Scott Russell's Napier Yard in London, and after two trial trips in 1859, set forth on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York on 17 June 1860. Though a failure at her original purpose of Passenger travel, she eventually found a role as an oceanic telegraph cable-layer. Under Captain Sir James Anderson, the Great Eastern played a significant role in laying the first lasting transatlantic telegraph cable, which enabled Telecommunication between Europe and North America.

Brunel did not live to see the bridge finished, although his colleagues and admirers at the Institution of Civil Engineers felt it would be a fitting memorial, and started to raise new funds and to amend the design. Work recommenced in 1862 and was completed in 1864, five years after Brunel's death. In 2011 it was suggested, by Historian and biographer Adrian Vaughan, that Brunel did not design the bridge, as eventually built, as the later changes to its design were substantial. His views reflected a sentiment stated fifty two years earlier by Tom Rolt in his 1959 book Brunel. Re-engineering of suspension chains recovered from an earlier suspension bridge was one of many reasons given why Brunel's design could not be followed exactly.

In 1865 the East London Railway Company purchased the Thames Tunnel for £200,000, and four years later the first trains passed through it. Subsequently, the tunnel became part of the London Underground system, and remains in use today, originally as part of the East London Line now incorporated into the London Overground.

Brunel was the subject of Great, a 1975 animated film directed by Bob Godfrey. It won the Academy Award for Animated Short Film at the 48th Academy Awards in March 1976.

In a 2002 public television poll conducted by the BBC to select the 100 Greatest Britons, Brunel was placed second, behind Winston Churchill. Brunel's life and works have been depicted in numerous books, films and television programs. The 2003 book and BBC TV series Seven Wonders of the Industrial World included a dramatisation of the building of the Great Eastern.

In 2006 the Royal Mint struck two £2 coins to "celebrate the 200th anniversary of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and his achievements". The first depicts Brunel with a section of the Royal Albert Bridge and the second shows the roof of Paddington Station. The Post Office issued a set of commemorative stamps.

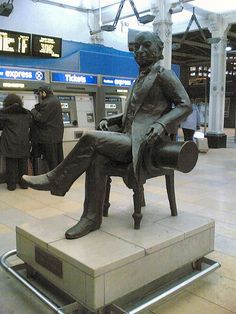

A celebrated Engineer in his era, Brunel remains revered today, as evidenced by numerous monuments to him. There are statues in London at Temple (pictured), Brunel University and Paddington station, and in Bristol, Plymouth, Swindon, Milford Haven and Saltash. A statue in Neyland in Pembrokeshire in Wales was stolen in August 2010. The topmast of the Great Eastern is used as a flagpole at the entrance to Anfield, Liverpool Football Club's ground. Contemporary locations bear Brunel's name, such as Brunel University in London, shopping centres in Swindon and also Bletchley, Milton Keynes, and a collection of streets in Exeter: Isambard Terrace, Kingdom Mews, and Brunel Close. A road, car park, and school in his home city of Portsmouth are also named in his honour, along with one of the city's largest public houses. There is an engineering lab building at the University of Plymouth named in his honour.

The steampunk musical group The Men That Will Not Be Blamed for Nothing performed a song called Brunel on their album This May Be The Reason Why The Men That Will Not Be Blamed For Nothing Cannot Be Killed By Conventional Weapons, released in 2012. The song makes reference to Brunel's achievements as an Engineer.

The 2013 album The Last Ship by Sting includes the song "Ballad of the Great Eastern".

Drawing on Brunel's experience with the Thames Tunnel, the Great Western contained a series of impressive achievements—soaring viaducts such as the one in Ivybridge, specially designed stations, and vast tunnels including the Box Tunnel, which was the longest railway tunnel in the world at that time. There is an anecdote that the Box Tunnel may have been deliberately aligned so that the rising sun shines all the way through it on Brunel's birthday.

Brunel is credited with turning the town of Swindon into one of the fastest growing towns in Europe during the 19th century. Brunel's choice to locate the Great Western Railway locomotive sheds there caused a need for housing for the workers, which in turn gave Brunel the impetus to build hospitals, churches and housing estates in what is known today as the 'Railway Village'. According to some sources, Brunel's addition of a Mechanics Institute for recreation and hospitals and clinics for his workers gave Aneurin Bevan the basis for the creation of the National Health Service.