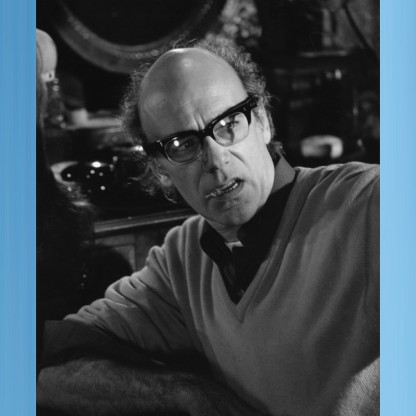

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Film Director |

| Birth Day | March 01, 1921 |

| Birth Place | Brighton, England, British |

| Age | 99 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 26 February 1995(1995-02-26) (aged 73)\nBerkshire, England |

| Birth Sign | Aries |

| Occupation | Film director |

| Years active | 1936–1992 |

| Spouse(s) | Christine Norden (1947–53) (divorced) Katherine Kath (1953-?) (divorced) Haya Harareet (1984–1995) (his death) |

Net worth: $3 Million (2024)

Jack Clayton, a renowned film director from British, has achieved substantial success in his career. As of 2024, his net worth is estimated to be $3 million, a testament to his immense talent and dedication. Clayton has made a significant impact in the film industry, known for his captivating storytelling and dynamic direction. With a successful career spanning several decades, he has undoubtedly left an indelible mark on the world of cinema.

Biography/Timeline

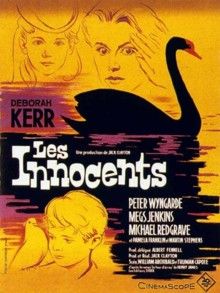

Starting out as a teenage studio "tea boy" in 1935, Clayton worked his way up through British film industry in a career that spanned nearly sixty years. He rapidly rose through a series of increasingly important roles in British film production, before shooting to international prominence as a Director with his Oscar-winning feature film debut, the landmark 1959 drama Room at the Top; this was followed in 1961 by the much-lauded horror film The Innocents, adapted from Henry James' The Turn of the Screw.

During the war years Clayton worked on many notable British features, including the first British Technicolor film Wings of the Morning (1937), and worked with visiting American Directors, including Thornton Freeland on Over the Moon (1939) and Tim Whelan on Q Planes (1939). As a second assistant Director he co-ordinated all three shooting units on Korda's lavish Technicolor fantasy The Thief of Baghdad (1940), having previously worked with Thief co-director Michael Powell on the noted "quota quickie" The Spy in Black (1939). He also gained invaluable editing experience assisting David Lean, who was the Editor (and uncredited director) of the screen adaptation of Shaw's Major Barbara (1941).

While in Service with the Royal Air Force film unit during World War II, Clayton shot his first film, the documentary Naples is a Battlefield (1944), representing the problems in the reconstruction of Naples, the first great city liberated in World War II, ruined after Allied bombing and destruction caused by the retreating Nazis. After the war, he was second-unit Director on Gordon Parry's Bond Street (1948) and production manager on Korda's An Ideal Husband (1947). Clayton married Actress Christine Norden in 1947, but they divorced in 1953. In the early 1950s Clayton became an associate Producer, working on several of the John and James Woolf's Romulus Films productions, including Moulin Rouge (1952) and Beat the Devil (1953), both directed by John Huston. It was during the making of Moulin Rouge that Clayton met his second wife, French Actress Katherine Kath (born Lilly Faess), who portrayed legendary can-can Dancer "La Goulue" in the film; they married in 1953, following Clayton's divorce from Norden, but the marriage was short-lived. It was also during this period that Clayton first met rising British star Laurence Harvey, with whom he worked on both The Good Die Young (1954) and I Am a Camera (1955).

In 1959, with funding from Romulus FIlms, Clayton directed his first full-length feature, a gritty contemporary social drama adapted from the novel by John Braine. Although it was the first and only occasion on which Clayton took over a project from another Director (in this case Peter Glenville), Room at the Top (1959) was a huge hit both critically and commercially, and it was one of the first British films to benefit from wide distribution in the USA. It established Clayton as one of the leading Directors of his day, made an international star of lead actor Laurence Harvey, won a slew of awards at major film festivals, and was nominated for six Oscars (including Best Director), with Simone Signoret winning Best Actress, and scriptwriter Neil Paterson winning for Best Writing, Screenplay (Based on Material from Another Medium). A harsh indictment of the British class system that has been credited with spearheading Britain's movement toward realism in films, it inaugurated a series of realist films known as the British New Wave, which featured, for that time, unusually sincere treatments of sexual mores, and introduced a new maturity into British cinema, breaking new ground as the first British feature film to openly discuss sex.

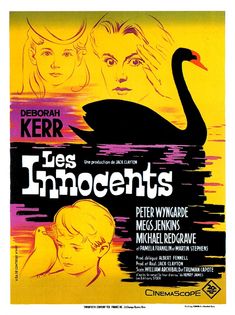

Setting a pattern that continued through the rest of his career, Clayton took a completely different tack with his second feature, on which he was both Producer and Director. The period ghost story The Innocents (1961) was adapted by Truman Capote from the classic Henry James short story The Turn of the Screw, which Clayton had first read when he was 10. By a fortunate coincidence, Clayton was contracted to make another film for 20th Century Fox, as was Actress Deborah Kerr, whom Clayton had long admired, so he was able to cast Kerr in the lead role as Miss Giddens, a repressed spinster who takes a job in a large, remote English country house; there working as the governess to an orphaned brother and sister, Giddens gradually comes to believe that her young charges are possessed by evil spirits.

The Pumpkin Eater (1964) featured a screenplay by leading British dramatist Harold Pinter, adapted from the novel by Penelope Mortimer, and cinematography by Clayton's longtime colleague Oswald Morris, with whom he had worked on many projects during their days with Romulus Films; it also marked the first of five collaborations between Clayton and noted French Composer Georges Delerue, and the first film appearance by rising star Maggie Smith. A psycho-sexual drama, set in contemporary London, it examined a marriage in crisis, with Anne Bancroft starring as an affluent middle-aged woman who becomes estranged from her unfaithful and emotionally distant husband, a successful author (Peter Finch). LIke both its predecessors, the film was widely acclaimed by critics - Harold Pinter won the 1964 BAFTA Award for Best British Screenplay, with Anne Bancroft winning both Best Actress at the Cannes Film Festival and the BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actress, and she was also nominated as Best Actress at the 37th Academy Awards (losing to Julie Andrews). Despite critical praise, the film failed to connect with audiences, and Clayton later expressed the view that, like several other of his projects, the film was a victim of "bad timing".

The only film Clayton was able to complete between 1968 and 1982 was his high-profile, Hollywood production of F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby (1974). The biggest and most expensive production of Clayton's career, the film had all the ingredients of success - produced by Broadway legend David Merrick, it boasted a screenplay by Francis Ford Coppola, cinematography by Douglas Slocombe, music by Nelson Riddle, two of the biggest stars of the period in Robert Redford and Mia Farrow, and a powerful supporting cast that included Bruce Dern, Karen Black, Sam Waterston, Scott Wilson, Lois Chiles and Hollywood veteran Howard Da Silva, who had also featured in the 1949 version of the film.

Clayton looked set for a brilliant Future, and he was highly regarded by peers and critics alike, but a number of overlapping factors hampered his career. He was a notably 'choosy' Director, who by his own admission "never made a film I didn't want to make", and he repeatedly turned down films (including Alien) that became huge hits for other Directors. But he was also dogged by bad luck and bad timing - the Hollywood studios labelled him as 'difficult', and studio politics quashed a string of planned films in the 1970s, which were either taken out of his hands, or cancelled in the final stages of preparation. In 1977, he suffered a double blow - his current film was cancelled just two weeks before shooting was due to begin, and a few months later he suffered a serious stroke which robbed him of the ability to speak, and put his career on hold for five years.

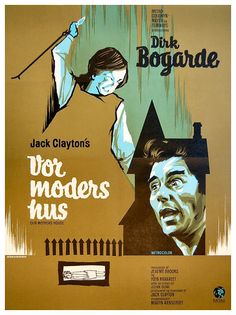

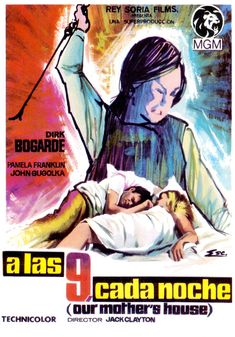

Despite his high critical standing, Clayton encountered repeated career setbacks after the release of Our Mother's House and over the 15 years between the release of Our Mother's House and Something Wicked This Way Comes, he was only able to complete one feature as a Director, The Great Gatsby, in 1974. One reason was Clayton's own perfectionism as a filmmaker; he was known for his discernment and taste, his painstaking and meticulous approach to his work, and his Desire not to repeat himself, and in his biographer's words, Clayton "never made a film he did not want to make". Consequently, he rejected many notable films in the wake of Room At The Top. In 1969, despite his love of the book, he turned down the chance to direct They Shoot Horses, Don't They? because he did not want to take over a film that had already been prepared and cast, and was ready to shoot - although his decision opened up a career-making opportunity for his replacement, Sydney Pollack. Later still, in 1977, he turned down the chance to direct the film that was eventually made as Alien by Ridley Scott.

In 1977, as compensation for the cancellation of Silence, Fox offered Clayton the chance to a new science fiction script co-credited to David Giler and Dan O'Bannon, but Clayton turned down the film (Alien), and it was ultimately given to Ridley Scott who, like Sydney Pollack before him, scored a career-making hit. A few months later, Clayton suffered a major stroke which robbed him of the ability to speak. He was helped to recover by his wife Haya, and a group of close friends, but he later revealed that he deliberately kept his condition secret because he feared he might not get work again if his affliction became known. He did not commit to another assignment for five years.

in the early 1980s, after Clayton had recovered from his stroke, Peter Douglas was able to sell the project to the Disney studios, with Clayton again signed to direct. Unfortunately, the film was fraught with problems throughout its production. Clayton and Bradbury reportedly fell out after the Director brought in British Writer John Mortimer to do an uncredited rewrite of the screenplay. Clayton made the film as a dark thriller, which saw him to return to themes he had explored in earlier films - the supernatural, and the exposure of children to evil. However, when he submitted his original cut, the studio expressed strong reservations about its length and pacing, and its commercial potential, and Disney then took the unusual step of holding the film back from release for almost a year. Clayton was reportedly sidelined (although he retained his Director credit) and Disney spent an additional six months, and some $5 million overhauling it, making numerous cuts and removing the original score (to make it more 'family-friendly'), and shooting new scenes (in some of which, because of the long delay caused by the reshoots, the two child stars were noticeably older and taller).

Clayton returned to directing in 1982, after a five-year hiatus forced on him by his 1977 stroke. His new film was another dream project that originated more than twenty years earlier, but which he had previously been unable to realize. Even before it came into Clayton's hands, the film version of Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes had a chequered history. Bradbury wrote the original short story in 1948, and in 1957 (reportedly after seeing Singing In The Rain some 40 times) Bradbury adapted it into a 70-page screen treatment and presented it as a gift to Gene Kelly. Clayton evidently met Bradbury ca. 1959 and expressed interest in directing the film, but Kelly was unable to raise the money to produce it, so Bradbury subsequently expanded the treatment into the novel version of the story, which was published in 1962.

The version of the film that hit the screens in 1983 was a compromise between Disney's insistence on a commercial film with 'family' appeal, and Clayton's original, darker vision of the story. To reduce costs, original Editor Argyle Nelson Jr was fired, and assistant Editor Barry Gordon was promoted to replace him (resulting in the film's dual Editor credit). Gordon was given the task of re-editing the film, and at Disney's insistence, he was obliged to remove some of Clayton's completed scenes. The most prominent casualty was the pioneering computer-generated animation sequence that was to have opened the film, which depicted the empty train bearing Dark's Carnival arriving in the town and magically unfolding itself into place. The much-heralded sequence (which was discussed in detail in a 1982 edition of Cinefantastique) would have been the first significant use of the new Technology in a major Hollywood movie, but it was almost entirely deleted, and in the final cut, only one brief CGI shot was retained. Another Clayton sequence that was removed featured a giant disembodied hand that reached into the boys' room and tried to grab them - this was deleted by the studio on the grounds that the mechanical effect was not realistic enough, and it was replaced with a newly filmed sequence in which the boys' room is invaded by spiders. (In 2012, co-star Shawn Carson recalled the harrowing experience of having to film the new scene, which was entirely done using real, live spiders). Bradbury was asked to write new opening narration (read by Arthur Hill) to help clarify the story, and new special effects were inserted, including the "cloud tank" storm effects.

Clayton's last feature film was the British-made The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne (1987), a film he had originally pitched in 1961. Adapted from his own novel by Brian Moore it starred Maggie Smith as a spinster who struggles with the emptiness of her life, and it again featured a score by Georges Delerue. It won Clayton critical plaudits for the first time in many years, and former collaborator Larry McMurtry described the film as "Brian Moore's best work, and perhaps Jack Clayton's too".

Clayton reunited with Maggie Smith and Georges Delerue in 1992 for what was to be his final screen project, and his first comedy - a feature-length BBC television adaptation of Memento Mori, based on the novel by Muriel Spark, for which he also co-wrote the screenplay and another project he had nursed since he first read the story, while making Room At The Top. Featuring a strong cast that included Smith, Michael Hordern, and veteran TV Comedian Thora Hird, Memento Mori expressed quietly moving meditations on disappointment and ageing. It aired in April 1992, just a month after Georges Delerue died in Hollywood, aged 67. According to Neil Sinyard Clayton was finally encouraged to make the film following the success of Driving Miss Daisy, "which proved that the theme of old age need not be box-office poison". Clayton successfully pitched it to the BBC, who were open to such a project following its recent successes with "made for TV" films like Truly Madly Deeply and Enchanted April. It was also shown at festivals worldwide, where it was well-received, and it won several awards, including a Best Screenplay award from the Writers' Guild of Great Britain.

When asked his religion, he replied: "ex-Catholic". Clayton was married three times, his first was to British Actress Christine Norden in 1947, but they divorced in 1953; the same year he married again to French Actress Katherine Kath, but this was short-lived. His third marriage, (some time in the mid-1960s) was to the Israeli Actress Haya Harareet, and this lasted until his death. Clayton died in hospital in Slough, England from a heart attack, following a short illness, on 25 February 1995.

Former colleague Jim Clark was given his major break by Clayton, who hired him as the Editor on The Innocents. They became close friends (and regular drinking partners) during the making of film. In his 2010 memoir Dream Repairman, Clark offered a number of insights into their personal and professional relationship, as well as the often contradictory personality traits exhibited by the Director, whom he recalled as "a very complex personality. The iron fist in the velvet glove."

Another major disappointment for both Clayton and his musical collaborator, Georges Delerue was the loss of the original score, which Disney rejected as being 'too dark' - it was removed at the studio's insistence, and replaced by a new score, written by American Composer James Horner. Delerue's Soundtrack (which the Composer considered the best of the music he wrote for Hollywood films) remained unheard in the Disney vaults until 2011, when the studio unusually gave permission for the French Universal label to issue 30 minutes of excerpts from the original 63 minutes of studio recordings on a limited edition CD (coupled with excerpts from another unused Delerue score, for Mike Nichols' Regarding Henry).