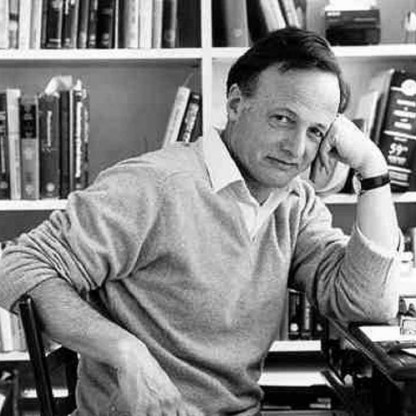

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Physicist |

| Birth Day | May 25, 1921 |

| Birth Place | Bad Kissingen, United States |

| Age | 102 YEARS OLD |

| Birth Sign | Gemini |

| Known for | Discovery of the muon neutrino |

| Spouse(s) | Cynthia Alff |

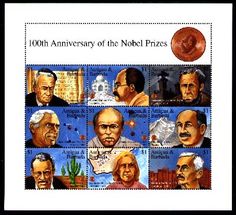

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physics (1988) National Medal of Science (1988) Matteucci Medal (1990) |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | University of California, Berkeley Columbia University CERN |

| Academic advisors | Edward Teller Enrico Fermi |

| Notable students | Melvin Schwartz Eric L. Schwartz David R. Nygren Theodore Modis |

Net worth: $19 Million (2024)

Jack Steinberger, a renowned and respected physicist based in the United States, is estimated to have a net worth of $19 million by 2024. With a notable career spanning several decades, Steinberger has made significant contributions to the field of particle physics, particularly in the study of subatomic particles. Throughout his scientific journey, he has received numerous accolades and honors, including the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1988. Steinberger's net worth reflects both his successful scientific endeavors and his dedication to advancing our understanding of the fundamental workings of the universe.

Biography/Timeline

Steinberger studied chemical engineering at Armour Institute of Technology (now Illinois Institute of Technology) but left after his scholarship ended to help supplement his family's income. He obtained a bachelor's degree in Chemistry from the University of Chicago, in 1942. Shortly thereafter, he joined the Signal Corps at MIT. With the help of the G.I. Bill, he returned to graduate studies at the University of Chicago in 1946, where he studied under Edward Teller and Enrico Fermi. His Ph.D. thesis concerned the Energy spectrum of electrons emitted in muon decay; his results showed that this was a three-body decay, and implied the participation of two neutral particles in the decay (later identified as the electron (

ν

e) and muon (

ν

μ) neutrinos) rather than one.

After receiving his doctorate, Steinberger attended the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton for a year. In 1949 he published a calculation of the lifetime of the neutral pion, which anticipated the study of anomalies in quantum field theory.

Steinberger accepted a faculty position at Columbia in 1950. The newly commissioned meson beam at Nevis Labs provided the tool for several important experiments. Measurements of the production cross section of pions on various nuclear targets showed that the pion has odd parity. A direct measurement of the production of pions on a liquid hydrogen target, then not a Common tool, provided the data needed to show that the pion has spin zero. The same target was used to observe the relative rare decay of neutral pions to a photon, an electron, and a positron. A related experiment measured the mass difference between the charged and neutral pions based on the angular correlation between the neutral pions produced when the negative pion is captured by the proton in the hydrogen nucleus. Other important experiments studied the angular correlation between electron-positron pairs in neutral pion decays, and established the rare decay of a charged pion to an electron and neutrino; the latter required use of a liquid-hydrogen bubble chamber.

During 1954–1955, Steinberger contributed to the development of the bubble chamber with the construction of a 15 cm device for use with the Cosmotron at Brookhaven National Laboratory. The experiment used a pion beam to produce pairs of hadrons with strange quarks in order to elucidate the puzzling production and decay properties of these particles. Somewhat later, in 1956, he used a 30 cm chamber outfitted with three cameras to discover the neutral Sigma hyperon and measure its mass. This observation was important for confirming the existence of the SU(3) flavor symmetry which hypothesizes the existence of the strange quark.

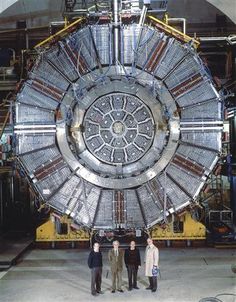

In the 1960s, the emphasis in the study of the weak interaction shifted from strange particles to neutrinos. Leon Lederman, Steinberger and Schwartz built large spark chambers at Nevis Labs and exposed them in 1961 to neutrinos produced in association with muons in the decays of charged pions and kaons. They used the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron (AGS) at Brookhaven, and obtained a number of convincing events in which muons were produced, but no electrons. This result, for which they received the Nobel Prize in 1988, proved the existence of a type of neutrino associated with the muon, distinct from the neutrino produced in beta decay.

The experiment used charged pion beams generated with the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron (AGS) at Brookhaven National Laboratory. The pions decayed to muons which were detected in front of a steel wall; the neutrinos were detected in spark chambers installed behind the wall. The coincidence of muons and neutrinos demonstrated that a second kind of neutrino was created in association with muons. Subsequent experiments proved this neutrino to be distinct from the first kind (electron-type). Steinberger, Lederman and Schwartz published their work in Physical Review Letters in 1962.

The CP violation (charge conjugation and parity) was established in the neutral kaon system in 1964. Steinberger recognized that the phenomenological parameter epsilon (ε) which quantifies the degree of CP violation could be measured in interference phenomena (See CP violation). In collaboration with Carlo Rubbia, he performed an experiment while on sabbatical at CERN during 1965 which demonstrated robustly the expected interference effect, and also measured precisely the difference in mass of the short-lived and long-lived neutral kaon masses.

In 1968, Steinberger left Columbia University and accepted a position as a department Director at CERN. He constructed an experiment there utilizing multi-wire proportional chambers (MWPC), recently invented by Georges Charpak. The MWPC's, augmented by micro-electronic amplifiers, allowed much larger samples of events to be recorded. Several results for neutral kaons were obtained and published in the early 1970s, including the observation of the rare decay of the neutral kaon to a muon pair, the time-dependence of the asymmetry for semi-leptonic decays, and a more precise measurement of the neutral kaon mass difference. A new era in experimental technique was opened.

These new techniques proved crucial for the first demonstration of direct CP-violation. The NA31 experiment at CERN was built in the early 1980s using the CERN SPS 400 GeV proton synchrotron. Aside from banks of MWPC's and a hadron calorimeter, it featured a liquid argon electromagnetic calorimeter with exceptional spatial and Energy resolution. NA31 showed that direct CP violation is real.

Jack Steinberger was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1988, "for the neutrino beam method and the demonstration of the doublet structure of the leptons through the discovery of the muon neutrino". He shares this prize with Leon M. Lederman and Melvin Schwartz. At the time, all three experimenters were at Columbia University.