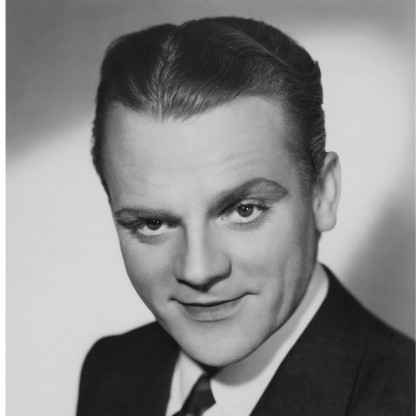

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Actor, Dancer |

| Birth Day | July 17, 1899 |

| Birth Place | New York City, United States |

| Age | 120 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | March 30, 1986(1986-03-30) (aged 86)\nStanford, New York, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Leo |

| Resting place | Gate of Heaven Cemetery |

| Occupation | Actor, dancer |

| Years active | 1919–1984 |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Vernon (1922–1986, his death) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | William Cagney (brother) Jeanne Cagney (sister) |

Net worth: $10 Million (2024)

James Cagney, renowned for his incredible talent as an actor and dancer, boasts an impressive net worth of $10 million as of 2024. His remarkable career in the entertainment industry has garnered him immense success and recognition throughout the United States. Cagney's extraordinary performances and versatility have made him a beloved figure in American cinema, winning him several prestigious awards and nominations. As an iconic figure in Hollywood, Cagney's net worth is a testament to his enduring legacy and undeniable impact on the world of film and dance.

Biography/Timeline

James Francis "Jimmy" Cagney was born on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in New York City. His biographers disagree as to the actual location: either on the corner of Avenue D and 8th Street or in a top-floor apartment at 391 East Eighth Street, the address that his birth certificate indicates. His Father, James Francis Cagney Sr. (1875–1918), was of Irish descent. At the time of his son's birth, he was a bartender and amateur boxer, though on Cagney's birth certificate, he is listed as a telegraphist. His mother was Carolyn (née Nelson; 1877–1945); her Father was a Norwegian ship captain while her mother was Irish.

Cagney, born in 1899 (prior to widespread use of automobiles), loved horses from childhood. As a child, he often sat on the horses of local deliverymen, and rode in horse-drawn streetcars with his mother. As an adult, well after horses were replaced by automobiles as the primary mode of transportation, Cagney raised horses on his farms, specializing in Morgans, a breed of which he was particularly fond.

The red-haired, blue-eyed Cagney graduated from Stuyvesant High School in New York City, in 1918, and attended Columbia College of Columbia University, where he intended to major in Art. He also took German and joined the Student Army Training Corps but dropped out after one semester, returning home upon the death of his Father during the 1918 flu pandemic.

While working at Wanamaker's Department Store in 1919, Cagney learned, from a colleague who had seen him dance, of a role in the upcoming production Every Sailor. A wartime play in which the chorus was made up of servicemen dressed as women, it was originally titled Every Woman. Cagney auditioned for the role of a chorus girl, despite considering it a waste of time; he knew only one dance step, the complicated Peabody, but he knew it perfectly. This was enough to convince the producers that he could dance, and he copied the other dancers' moves while waiting to go on. He did not find it odd to play a woman, nor was he embarrassed. He later recalled how he was able to shed his own natural shy persona when he stepped onto the stage: "For there I am not myself. I am not that fellow, Jim Cagney, at all. I certainly lost all consciousness of him when I put on skirts, wig, paint, powder, feathers and spangles."

In his autobiography, Cagney said that as a young man, he had no political views, since he was more concerned with where the next meal was coming from. However, the emerging labor movement of the 1920s and 1930s soon forced him to take sides. The first version of the National Labor Relations Act was passed in 1935 and growing tensions between labor and management fueled the movement. Fanzines in the 1930s, however, described his politics as "radical".

In 1920, Cagney was a member of the chorus for the show Pitter Patter, where he met Frances Willard "Billie" Vernon. They married on September 28, 1922, and the marriage lasted until his death in 1986. Frances Cagney died in 1994. In 1941, they adopted a son whom they named James Francis Cagney III, and later a daughter, Cathleen "Casey" Cagney. Cagney was a very private man, and while he was willing to give the press opportunities for photographs, he generally spent his time out of the public eye.

After years of touring and struggling to make money, Cagney and Vernon moved to Hawthorne, California, in 1924, partly for Cagney to meet his new mother-in-law, who had just moved there from Chicago, and partly to investigate breaking into the movies. Their train fares were paid for by a friend, the press officer of Pitter Patter, who was also desperate to act. They were not successful at first; the dance studio Cagney set up had few clients and folded, and Vernon and he toured the studios, but garnered no interest. Eventually, they borrowed some money and headed back to New York via Chicago and Milwaukee, enduring failure along the way when they attempted to make money on the stage.

Cagney secured his first significant nondancing role in 1925. He played a young tough guy in the three-act play Outside Looking In by Maxwell Anderson, earning $200 a week. As with Pitter Patter, Cagney went to the audition with little confidence he would get the part. He had no experience with drama at this point. Cagney felt that he only got the role because his hair was redder than that of Alan Bunce, the only other red-headed performer in New York. Both the play and Cagney received good reviews; Life magazine wrote, "Mr. Cagney, in a less spectacular role [than his co-star] makes a few minutes silence during his mock-trial scene something that many a more established actor might watch with profit." Burns Mantle wrote that it "...contained the most honest acting now to be seen in New York."

Cagney secured the lead role in the 1926–27 season West End production of Broadway by George Abbott. The show's management insisted that he copy Broadway lead Lee Tracy's performance, despite Cagney's discomfort in doing so, but the day before the show sailed for England, they decided to replace him. This was a devastating turn of events for Cagney; apart from the logistical difficulties this presented—the couple's luggage was in the hold of the ship and they had given up their apartment. He almost quit show Business. As Vernon recalled, "Jimmy said that it was all over. He made up his mind that he would get a job doing something else."

He had built a reputation as an innovative Teacher, so when he was cast as the lead in Grand Street Follies of 1928, he was also appointed the Choreographer. The show received rave reviews and was followed by Grand Street Follies of 1929. These roles led to a part in George Kelly's Maggie the Magnificent, a play the critics disliked, though they liked Cagney's performance. Cagney saw this role (and Women Go on Forever) as significant because of the talented Directors he met. He learned "...what a Director was for and what a Director could do. They were Directors who could play all the parts in the play better than the actors cast for them."

With the introduction of the United States Motion Picture Production Code of 1930, and particularly its edicts concerning on-screen violence, Warners allowed Cagney a change of pace. They cast him in the comedy Blonde Crazy, again opposite Blondell. As he completed filming, The Public Enemy was filling cinemas with all-night showings. Cagney began to compare his pay with his peers, thinking his contract allowed for salary adjustments based on the success of his films. Warner Bros. disagreed, however, and refused to give him a raise. The studio heads also insisted that Cagney continue promoting their films, even ones he was not in, which he opposed. Cagney moved back to New York, leaving his brother Bill to look after his apartment.

This somewhat exaggerated view was enhanced by his public contractual wranglings with Warner Bros. at the time, his joining of the Screen Actors Guild in 1933, and his involvement in the revolt against the so-called "Merriam tax". The "Merriam tax" was an underhanded method of funneling studio funds to politicians; during the 1934 Californian gubernatorial campaign, the studio executives would 'tax' their actors, automatically taking a day's pay from their biggest-earners, ultimately sending nearly half a million dollars to the gubernatorial campaign of Frank Merriam. Cagney (as well as Jean Harlow) publicly refused to pay and Cagney even threatened that, if the studios took a day's pay for Merriam's campaign, he would give a week's pay to Upton Sinclair, Merriam's opponent in the race.

Cagney was accused of being a communist sympathizer in 1934, and again in 1940. The accusation in 1934 stemmed from a letter police found from a local Communist official that alleged that Cagney would bring other Hollywood stars to meetings. Cagney denied this, and Lincoln Steffens, husband of the letter's Writer, backed up this denial, asserting that the accusation stemmed solely from Cagney's donation to striking cotton workers in the San Joaquin Valley. william Cagney claimed this donation was the root of the charges in 1940. Cagney was cleared by U.S. Representative Martin Dies Jr., on the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Cagney's last movie in 1935 was Ceiling Zero, his third film with Pat O'Brien. O'Brien received top billing, which was a clear breach of Cagney's contract. This, combined with the fact that Cagney had made five movies in 1934, again against his contract terms, caused him to bring legal proceedings against Warner Bros. for breach of contract. The dispute dragged on for several months. Cagney received calls from David Selznick and Sam Goldwyn, but neither felt in a position to offer him work while the dispute went on. Meanwhile, while being represented by his brother william in court, Cagney went back to New York to search for a country property where he could indulge his passion for farming.

Cagney also became involved in political causes, and in 1936, agreed to sponsor the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. Unknown to Cagney, the League was in fact a front organization for the Communist International (Comintern), which sought to enlist support for the Soviet Union and its foreign policies.

Cagney starred as Rocky Sullivan, a gangster fresh out of jail and looking for his former associate, played by Humphrey Bogart, who owes him money. While revisiting his old haunts, he runs into his old friend Jerry Connolly, played by O'Brien, who is now a priest concerned about the Dead End Kids' futures, particularly as they idolize Rocky. After a messy shootout, Sullivan is eventually captured by the police and sentenced to death in the electric chair. Connolly pleads with Rocky to "turn yellow" on his way to the chair so the Kids will lose their admiration for him, and hopefully avoid turning to crime. Sullivan refuses, but on his way to his execution, he breaks down and begs for his life. It is unclear whether this cowardice is real or just feigned for the Kids' benefit. Cagney himself refused to say, insisting he liked the ambiguity. The film is regarded by many as one of Cagney's finest, and garnered him an Academy Award for Best Actor nomination for 1938. He lost to Spencer Tracy in Boys Town. Cagney had been considered for the role, but lost out on it due to his typecasting. (He also lost the role of Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne in Knute Rockne, All American to his friend Pat O'Brien for the same reason.) Cagney did, however, win that year's New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actor.

During his first year back at Warner Bros., Cagney became the studio's highest earner, making $324,000. He completed his first decade of movie-making in 1939 with The Roaring Twenties, his first film with Raoul Walsh and his last with Bogart. After The Roaring Twenties, it would be a decade before Cagney made another gangster film. Cagney again received good reviews; Graham Greene stated, "Mr. Cagney, of the bull-calf brow, is as always a superb and witty actor". The Roaring Twenties was the last film in which Cagney's character's violence was explained by poor upbringing, or his environment, as was the case in The Public Enemy. From that point on, violence was attached to mania, as in White Heat. In 1939, Cagney was second to only Gary Cooper in the national acting wage stakes, earning $368,333.

After the war, Cagney's politics started to change. He had worked on Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt's presidential campaigns, including the 1940 presidential election against Wendell Willkie. However, by the time of the 1948 election, he had become disillusioned with Harry S. Truman, and voted for Thomas E. Dewey, his first non-Democratic vote.

Cagney became President of the Screen Actors Guild in 1942 for a two-year term. He took a role in the Guild's fight against the Mafia, which had begun to take an active interest in the movie industry. His wife, Billie Vernon, once received a phone call telling her that Cagney was dead. Cagney alleged that, having failed to scare off the Guild and him, they sent a hitman to kill him by dropping a heavy light onto his head. Upon hearing of the rumor of a hit, George Raft made a call, and the hit was supposedly canceled.

James Cagney won the Academy Award in 1943 for his performance as George M. Cohan in Yankee Doodle Dandy.

Cagney's portrayal of Cody Jarrett in the 1949 film White Heat is one of his most memorable. Cinema had changed in the 10 years since Walsh last directed Cagney (in The Strawberry Blonde), and the actor's portrayal of Gangsters had also changed. Unlike Tom Powers in The Public Enemy, Jarrett was portrayed as a raging lunatic with few if any sympathetic qualities. In the 18 intervening years, Cagney's hair had begun to gray, and he developed a paunch for the first time. He was no longer a romantic commodity, and this was reflected in his performance. Cagney himself had the idea of playing Jarrett as psychotic; he later stated, "it was essentially a cheapie one-two-three-four kind of thing, so I suggested we make him nuts. It was agreed so we put in all those fits and headaches."

The film was a critical success, though some critics wondered about the social impact of a character that they saw as sympathetic. Cagney was still struggling against his gangster typecasting. He said to a Journalist, "It's what the people want me to do. Some day, though, I'd like to make another movie that kids could go and see." However, Warner Bros., perhaps searching for another Yankee Doodle Dandy, assigned Cagney a musical for his next picture, 1950's The West Point Story with Doris Day, an Actress he admired.

His next film, Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye, was another gangster movie, which was the first by Cagney Productions since its acquisition. While compared unfavorably to White Heat by critics, it was fairly successful at the box office, with $500,000 going straight to Cagney Productions' Bankers to pay off their losses. Cagney Productions was not a great success, however, and in 1953, after william Cagney produced his last film, A Lion Is in the Streets, the company came to an end.

In 1955, having shot three films, Cagney bought a 120-acre (0.49 km) farm in Stanfordville, Dutchess County, New York, for $100,000. Cagney named it Verney Farm, taking the first syllable from Billie's maiden name and the second from his own surname. He turned it into a working farm, selling some of the dairy cattle and replacing them with beef cattle. He expanded it over the years to 750 acres (3.0 km). Such was Cagney's enthusiasm for agriculture and farming that his diligence and efforts were rewarded by an honorary degree from Florida's Rollins College. Rather than just "turning up with Ava Gardner on my arm" to accept his honorary degree, Cagney turned the tables upon the college's faculty by writing and submitting a paper on soil conservation.

In 1956, Cagney undertook one of his very rare television roles, starring in Robert Montgomery's Soldiers From the War Returning. This was a favor to Montgomery, who needed a strong fall season opener to stop the network from dropping his series. Cagney's appearance ensured that it was a success. The actor made it clear to reporters afterwards that television was not his medium: "I do enough work in movies. This is a high-tension Business. I have tremendous admiration for the people who go through this sort of thing every week, but it's not for me."

Later in 1957, Cagney ventured behind the camera for the first and only time to direct Short Cut to Hell, a remake of the 1941 Alan Ladd film This Gun for Hire, which in turn was based on the Graham Greene novel A Gun for Sale. Cagney had long been told by friends that he would make an excellent Director, so when he was approached by his friend, Producer A. C. Lyles, he instinctively said yes. He refused all offers of payment, saying he was an actor, not a Director. The film was low budget, and shot quickly. As Cagney recalled, "We shot it in twenty days, and that was long enough for me. I find directing a bore, I have no Desire to tell other people their business".

In 1959, Cagney played a labor leader in what proved to be his final musical, Never Steal Anything Small, which featured a comical song and dance duet with Cara Williams, who played his girlfriend.

For his contributions to the film industry, Cagney was inducted into the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960 with a motion pictures star located at 6504 Hollywood Boulevard.

In 1974, Cagney received the American Film Institute's Life Achievement Award. Charlton Heston, in announcing that Cagney was to be honored, called him "...one of the most significant figures of a generation when American film was dominant, Cagney, that most American of actors, somehow communicated eloquently to audiences all over the world ...and to actors as well."

While at Coldwater Canyon in 1977, Cagney had a minor stroke. After two weeks in the hospital, Zimmermann became his full-time caregiver, traveling with Billie Vernon and him wherever they went. After the stroke, Cagney was no longer able to undertake many of his favorite pastimes, including horseback riding and dancing, and as he became more depressed, he even gave up painting. Encouraged by his wife and Zimmermann, Cagney accepted an offer from the Director Miloš Forman to star in a small but pivotal role in the film Ragtime (1981).

He received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1980, and a Career Achievement Award from the U.S. National Board of Review in 1981. In 1984, Ronald Reagan awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Cagney's son married Jill Lisbeth Inness in 1962. The couple had two children, James IV and Cindy. James Cagney III died from a heart attack on January 27, 1984 in Washington, DC, two years before his father's death. He had become estranged from his Father and had not seen or talked to him since 1982.

Cagney died at his Dutchess County farm in Stanfordville, New York, on Easter Sunday 1986, of a heart attack. He was 86 years old. He died 4 days after his brother William’s 81st birthday. A funeral Mass was held at Manhattan's St. Francis de Sales Roman Catholic Church. The eulogy at the funeral was given by his close friend, who was also the President of the United States at the time, Ronald Reagan. His pallbearers included the boxer Floyd Patterson, the Dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov (who had hoped to play Cagney on Broadway), actor Ralph Bellamy, and the Director Miloš Forman. Governor Mario M. Cuomo and Mayor Edward I. Koch were also in attendance at the Service.

In 1999, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 33-cent stamp honoring Cagney.

Cagney's daughter Cathleen married Jack W. Thomas in 1962. She, too, was estranged from her Father during the final years of his life. She died on August 11, 2004.

As a young man, Cagney became interested in farming – sparked by a soil conservation lecture he had attended – to the extent that during his first walkout from Warner Bros., he helped to found a 100-acre (0.40 km) farm in Martha's Vineyard. Cagney loved that no concrete roads surrounded the property, only dirt tracks. The house was rather run-down and ramshackle, and Billie was initially reluctant to move in, but soon came to love the place, as well. After being inundated by movie fans, Cagney sent out a rumor that he had hired a gunman for security. The ruse proved so successful that when Spencer Tracy came to visit, his taxi driver refused to drive up to the house, saying, "I hear they shoot!" Tracy had to go the rest of the way on foot.

Cagney was a keen Sailor and owned boats harbored on both US coasts, His joy in sailing, however, did not protect him from occasional seasickness—becoming ill, sometimes, on a calm day while weathering rougher, heavier seas at other times. Cagney greatly enjoyed painting, and claimed in his autobiography that he might have been happier, if somewhat poorer, as a Painter than a movie star. The renowned Painter Sergei Bongart taught Cagney in his later life and owned two of Cagney's works. Cagney often gave away his work, but refused to sell his paintings, considering himself an amateur. He signed and sold only one painting, purchased by Johnny Carson to benefit a charity.

On May 19, 2015, a new musical celebrating Cagney, and dramatizing his relationship with Warner Bros., opened off-Broadway in New York City at the York Theatre. Cagney, The Musical has since moved to the Westside Theatre.