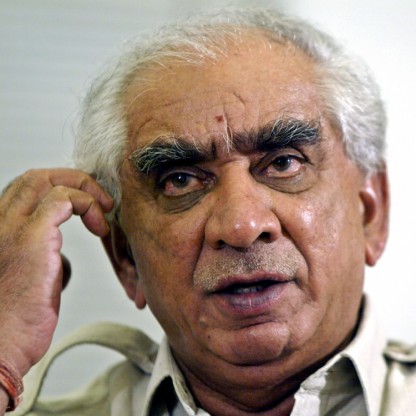

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Birth Day | March 27, 1912 |

| Birth Place | Portsmouth, British |

| Age | 108 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 26 March 2005(2005-03-26) (aged 92)\nRingmer, East Sussex, England |

| Birth Sign | Aries |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Preceded by | Arthur Evans |

| Succeeded by | Alun Michael |

| Prime Minister | Clement Attlee |

| Deputy | Michael Foot |

| Leader | Hugh Gaitskell George Brown (Acting) Harold Wilson |

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouse(s) | Audrey Moulton (m. 1938; d. 2005) |

| Children | 3, including Margaret Jay |

| Parents | James Callaghan Charlotte Cundy |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/branch | Royal Navy |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Battles/wars | Second World War |

Net worth: $20 Million (2024)

James Callaghan, a prominent British political leader, is estimated to have a net worth of $20 million in 2024. Renowned for his contributions to the political landscape, Callaghan had a successful career serving the United Kingdom in prominent positions such as Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer. His net worth reflects not only his salary and benefits from his political roles but also potentially earnings from book sales and speaking engagements. Callaghan's wealth stands as a testament to his significant influence and enduring legacy in British politics.

Famous Quotes:

Nowadays exchange rates can swing to and fro continually by amount greater than that, without attracting much attention outside the City columns of the newspapers. It may be difficult to understand how great a political humiliation this devaluation appeared at the time—above all to Wilson and his Chancellor, Jim Callaghan, who felt he must resign over it. Callaghan's personal distress was increased by a careless answer he gave to a backbencher's question two days before the formal devaluation. This cost Britain several hundred million pounds.

Biography/Timeline

His mother was Charlotte Callaghan (née Cundy; (1879–1961) an English Baptist. As the Catholic Church at the time refused to marry Catholics to members of other denominations, James Callaghan senior abandoned Catholicism and married Charlotte in a Baptist chapel. Their first child was Dorothy Gertrude Callaghan (1904–82).

Leonard James Callaghan was born at 38 Funtington Road, Copnor, Portsmouth, England, on 27 March 1912. He took his middle name from his father, James (1877–1921), who was the son of an Irish Catholic father who had fled to England during the Irish potato famine, and a Jewish mother. Callaghan's father ran away from home in the 1890s to join the Royal Navy; as he was a year too young to enlist, he gave a false date of birth and changed his surname from Garogher to Callaghan, so that his true identity could not be traced. He rose to the rank of Chief Petty Officer.

He attended Portsmouth Northern Secondary School (now Mayfield School). He gained the Senior Oxford Certificate in 1929, but could not afford entrance to university and instead sat the civil Service Entrance Exam. At the age of 17, Callaghan left to work as a clerk for the Inland Revenue. While working as a tax inspector, Callaghan was instrumental in establishing the Association of Officers of Taxes as a trade union for those in his profession and became a member of its national executive. While at the Inland Revenue offices in Kent, in 1931, he joined the Maidstone branch of the Labour Party. In 1934, he was transferred to Inland Revenue offices in London. Following a merger of unions in 1936, Callaghan was appointed a full-time union official and to the post of Assistant Secretary of the Inland Revenue Staff Federation and resigned from his Civil Service duties.

Callaghan's interests included rugby (he played lock for Streatham RFC before the Second World War), tennis and agriculture. He married Audrey Elizabeth Moulton, whom he had met when they both worked as Sunday School teachers at the local Baptist church, in July 1938 and had three children – one son and two daughters.

Callaghan joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve as an Ordinary Seaman in 1942; he served in the East Indies Fleet and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant in April 1944. While training for his promotion, his medical examination revealed that he was suffering from tuberculosis so he was admitted to the Royal Naval Hospital Haslar in Gosport near Portsmouth. After he recovered, he was discharged and assigned to duties with the Admiralty in Whitehall. He was assigned to the Japanese section and wrote a Service manual for the Royal Navy The Enemy Japan. Callaghan would become (as of 2018) the last British prime minister to be an armed forces veteran and the only one ever to have served in the Royal Navy.

Labour won a landslide victory on 26 July 1945 bringing Clement Attlee to power. Callaghan won his Cardiff South seat in the 1945 UK general election (and would hold a Cardiff-area seat continuously until 1987). He defeated the sitting Conservative incumbent candidate, Sir Arthur Evans, by 17,489 votes to 11,545. He campaigned on such issues as the rapid demobilisation of the armed forces and for a new housing construction programme. He stood in the left wing of the Party, and in 1945 voted against closer financial ties with the United States.

Callaghan was soon appointed Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Transport in 1947 where, advised by the young chief constable of Hertfordshire, Sir Arthur Young, his term saw important improvements in road safety, notably the introduction of zebra crossings, and an extension in the use of cat's eyes. He moved to be Parliamentary and Financial Secretary to the Admiralty from 1950 where he was a delegate to the Council of Europe and resisted plans for a European army.

Callaghan was popular with Labour MPs and was elected to the Shadow Cabinet every year while the Labour Party was in opposition from 1951 to 1964. He was now a staunch Gaitskellite on the right wing. He was Parliamentary Adviser to the Police Federation from 1955 to 1960 when he negotiated an increase in police pay with the then general secretary Arthur Charles Evans. He ran for the Deputy Leadership of the party in 1960 as an opponent of unilateral nuclear disarmament, and despite the other candidate of the Labour right (George Brown) agreeing with him on this policy, he forced Brown to a second vote. In November 1961, Callaghan became Shadow chancellor. When Hugh Gaitskell died in January 1963, Callaghan ran to succeed him, but came third in the leadership contest, which was won by Harold Wilson. However, he did gain the support of right-wingers, such as Denis Healey and Anthony Crosland, who wanted to prevent Wilson from being elected leader but who also did not trust George Brown.

In October 1964, Conservative Prime Minister Sir Alec Douglas-Home (who had only been in power for 12 months since the resignation of Harold Macmillan) called a general election. It was a tough election, but Labour won a narrow majority, gaining 56 seats (a total of 317 to the Conservatives' 304). The new Labour government under Harold Wilson immediately faced economic problems and Wilson acted within his first hours to appoint Callaghan as Chancellor of the Exchequer. The previous Conservative Chancellor Reginald Maudling had initiated fiscally expansionary measures which had helped create a pre-election economic boom; by greatly increasing domestic demand this had caused imports to grow much faster than exports, thus when Labour entered government they faced a balance of payments deficit of £800 million and an immediate Sterling crisis. Both Wilson and Callaghan took a strong stance against devaluation of Sterling, partly due to the perception that the devaluation carried out by the previous Labour government in 1949 had contributed to that government's downfall. The alternative to devaluation however, was a series of austerity measures designed to reduce demand in the economy in order to reduce imports and stabilise the balance of payments and the value of sterling.

His second budget came on 6 April 1965, in which he announced efforts to deflate the economy and reduce home import demand by £250 million. Shortly afterwards, the bank rate was reduced from 7% down to 6%. For a brief time, the economy and British financial market stabilised, allowing in June for Callaghan to visit the United States and to discuss the state of the British economy with President Lyndon B. Johnson and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

In July, the pound came under extreme pressure and Callaghan was forced to create harsh temporary measures to demonstrate control of the economy. These include delaying all current government building projects and postponing new pension plans. The alternative was to allow the pound to float or to devalue it. Callaghan and Wilson, however, were again Adam Ant that a devaluation of the pound would create new social and economic problems and continued to take a firm stance against it. The government continued to struggle both with the economy and with the slender majority which, by 1966, had been reduced to one. On 28 February, Harold Wilson formally announced an election for 31 March 1966. On 1 March, Callaghan gave a 'little budget' to the Commons and announced the historic decision that the UK would adopt decimal currency. It was actually not until 1971, under a Conservative government, that the United Kingdom moved from the system of pounds, shillings and pence to a decimal system of 100 pence to the pound. He also announced a short-term mortgage scheme which allowed low-wage earners to maintain mortgage schemes in the face of economic difficulties. Soon afterwards, in the 1966 general election Labour won 363 seats compared to 252 seats against the Conservatives, giving the Labour government a large majority of 97.

Before the devaluation, Jim Callaghan had announced publicly to the Press and the House of Commons that he would not devalue, something he later said was necessary to maintain confidence in the pound and avoid creating jitters in the financial markets. Callaghan immediately offered his resignation as Chancellor and increasing political opposition forced Wilson to accept it. Wilson then moved Roy Jenkins, the Home Secretary, to the Chancellor of the Exchequer and Callaghan became the new Home Secretary on 30 November 1967.

Callaghan was also responsible for the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968; a controversial piece of legislation prompted by Conservative assertions that an influx of Kenyan Asians would soon inundate the country. It passed through the Commons in a week and placed entry controls on holders of British passports who had "no substantial connection" with Britain by setting up a new system. In his memoirs Time and Chance, Callaghan wrote that introducing the Commonwealth Immigrants Bill had been an unwelcome task but that he did not regret it. He claimed the Asians had "discovered a loophole" and he told a BBC interviewer: "Public opinion in this country was extremely agitated, and the consideration that was in my mind was how we could preserve a proper sense of order in this country and, at the same time, do justice to these people—I had to balance both considerations". An opponent of the Act, Conservative MP Ian Gilmour, asserted that it was "brought in to keep the blacks out. If it had been the case that it was 5,000 white settlers who were coming in, the newspapers and politicians, Callaghan included, who were making all the fuss would have been quite pleased".

His wife, Audrey, a former chairman (1969–82) of Great Ormond Street Hospital, spotted a letter to a newspaper which pointed out that the copyright of Peter Pan, which had been assigned by J. M. Barrie to the hospital, was going to expire at the end of that year, 1987 (50 years after Barrie's death, the current copyright term). In 1988, Callaghan moved an amendment to the Copyright Designs & Patents Act, then under consideration in the House of Lords, to grant the hospital a right to royalty in perpetuity despite the lapse of copyright, and it was passed by the government.

Historians Alan Sked and Chris Cook have summarised the general consensus of historians regarding Labour in power in the 1970s:

When Wilson won the next general election and returned as Prime Minister in March 1974, he appointed Callaghan as Foreign Secretary which gave him responsibility for renegotiating the terms of the United Kingdom's membership of the Common Market. When the talks concluded, Callaghan led the Cabinet in declaring the new terms acceptable and he supported a "Yes" vote in the 1975 referendum.

After four decades, the historiography on him is still contested territory. The left wing of the Labour Party considers him a traitor whose betrayals of true socialism laid the foundations for Thatcherism. They point to his decision in 1976 to allow the International Monetary Fund to control the government budget. They accuse him of abandoning the traditional Labour commitment to full employment. They blame his rigorous pursuit of a policy of controlling income growth for the "Winter of Discontent". Writers on the right of the Labour Party complained that he was a weak leader who was unable to stand up to the left. The "New Labour" Writers who admire Tony Blair identify him with the old-style partisanship that was a dead end, which a new generation of modernisers had to repudiate. Practically all commentators agree that Callaghan made a serious mistake by not calling an election in the autumn of 1978. Bernard Donoughue, a senior official in his government, depicts Callaghan as a strong and efficient administrator who stood heads above his predecessor Harold Wilson. The standard scholarly biography by Kenneth Morgan is generally favourable – at least for the middle of his premiership – while admitting failures at the beginning, at the end, and in his leadership role after Thatcher's victory. The treatment found in most textbooks and surveys of the period remains largely negative.

Callaghan's failure to call an election during 1978 was widely seen as a political miscalculation; indeed, he himself later admitted that not calling an election was an error of judgement. However, private polling by the Labour Party in the autumn of 1978 had shown the two main parties with about the same level of support. After losing power in 1979, Labour would spend the next 18 years in opposition.

On 28 March 1979, the House of Commons passed a Motion of No Confidence by one vote, 311–310, which forced Callaghan to call a general election that was held on 3 May. The Conservatives under Margaret Thatcher ran a campaign on the slogan "Labour Isn't Working" and won the election.

Notwithstanding electoral defeat, Callaghan stayed on as Labour leader until 15 October 1980, shortly after the party conference had voted for a new system of election by electoral college involving the individual members and trade unions. His resignation ensured that his successor would be elected by MPs only. After a campaign that laid bare the deep internal divisions of the parliamentary Labour Party, Michael Foot narrowly defeated Denis Healey on 10 November in the second round of the election to succeed Callaghan as party leader. Foot had been a relatively late entrant to the contest and his decision to stand ended the chances of Peter Shore.

In 1982, along with his friend, Gerald Ford, he co-founded the annual AEI World Forum.

In 1983, he attacked Labour's plans to reduce defence, and the same year became Father of the House as the longest continually-serving member of the Commons.

In 1987, he was made a Knight of the Garter and stood down at the 1987 general election after 42 years as an MP. Shortly afterwards, he was elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, of the City of Cardiff in the Royal County of South Glamorganshire. In 1987, his autobiography, Time and Chance, was published. He also served as a non-executive Director of the Bank of Wales.

In July 1996, he was awarded an honorary degree from the Open University as Doctor of the University.

Tony Benn recorded in his diary entry of 3 April 1997 that during the 1997 general election campaign, Callaghan was telephoned by a volunteer at Labour headquarters asking him if he would be willing to become more active in the party. According to Benn:

In October 1999, Callaghan told The Oldie Magazine that he would not be surprised to be considered as Britain's worst Prime Minister in 200 years. He also admitted in this interview that he "must carry the can" for the Winter of Discontent.

One of his final public appearances came on 29 April 2002, when shortly after his 90th birthday, he sat alongside the then-Prime Minister Tony Blair and three other surviving former Prime Ministers at the time - Edward Heath, Margaret Thatcher and John Major at Buckingham Palace for a dinner which formed part of the celebrations for the Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II, alongside his daughter Margaret, Baroness Jay, who had served as Leader of the House of Lords from 1998-2001.

Callaghan died on 26 March 2005 at Ringmer, East Sussex, of lobar pneumonia, cardiac failure and kidney failure. He would have been 93 the following day. He died just 11 days after his wife of 67 years, who had spent the last four years of her life in a nursing home due to Alzheimer's disease. He died as the longest-lived former UK Prime Minister, having beaten Harold Macmillan's record 39 days earlier. Lord Callaghan was cremated, and his ashes were scattered in a flowerbed around the base of the Peter Pan statue near the entrance of London's Great Ormond Street Hospital, where his wife had formerly been chair of the board of governors.

Callaghan's time as Prime Minister was dominated by the troubles in running a Government with a minority in the House of Commons: he was forced to make deals with minor parties to survive – including the Lib–Lab pact, and he had been forced to accept a referendum on devolution in Scotland as well as one in Wales (the former went in favour but did not reach the required majority, and the latter went heavily against). He also became prime minister at a time when Britain was suffering from double-digit percentage inflation and rising unemployment. He responded to the economic crises by adopting deflationary policies to reduce inflation, and cutting public expenditure – a precursor to the monetarist economic policies that the next government, a Conservative one led by Margaret Thatcher, would pursue to ease the crises.

Whilst on leave from the navy, Callaghan was selected as a Parliamentary candidate for Cardiff South — he narrowly won the local party ballot with twelve votes against the next highest candidate George Thomas with eleven. He had been encouraged to put his name forward for the Cardiff South seat by his friend Dai Kneath, a member of the IRSF National executive from Swansea, who was in turn an associate and friend of the local Labour Party secretary Bill Headon.