Age, Biography and Wiki

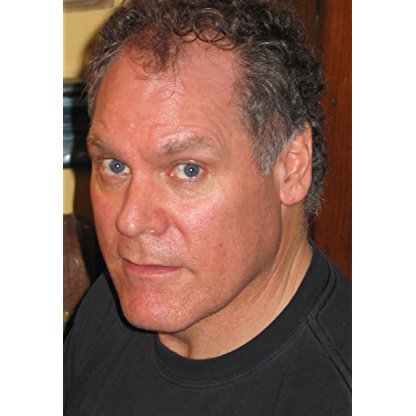

| Who is it? | Actor, Stunts, Producer |

| Birth Day | October 19, 1610 |

| Age | 409 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 21 July 1688(1688-07-21) (aged 77)\nKingston Lacy, Dorset, England |

| Birth Sign | Sagittarius |

| Preceded by | 2nd Earl of Leicester |

| Succeeded by | Viscount Lisle |

| Monarch | Charles I |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey, London |

| Political party | Cavalier |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Preston, Baroness Dingwall (m. 1630–1684); her death |

| Children | 7 children |

| Education | Trinity College |

| Profession | Soldier, official |

| Service/branch | English Army Irish Confederates |

| Years of service | 1639–1651 |

| Rank | Commander-in-chief General Commandant |

| Battles/wars | Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1639—1651) Second Bishops' War 1st Siege od Drogheda Battle of Kilrush Battle of New Ross Battle of Rathmines 2nd Siege od Drogheda |

Net worth

Jaymes Butler, a renowned figure in the entertainment industry, has made quite a name for himself over the years. With his diverse talents as an actor, stuntsman, and producer, Butler has garnered a significant amount of wealth. In 2024, his net worth is estimated to range between $100,000 and $1 million, highlighting his success in the entertainment business. What makes Butler's accomplishments even more remarkable is the fact that he was born in 1610, showcasing his longevity and enduring passion for his craft. Despite being an actor from a different era, Butler's talents have evidently transcended time, leaving behind a lasting legacy in the industry.

Famous Quotes:

- A Man of Plato's grand nobility,

- An inbred greatness, innate honesty;

- A Man not form'd of accidents, and whom

- Misfortune might oppress, not overcome

- Who weighs himself not by opinion

- But conscience of a noble action.

Biography/Timeline

James Butler was the eldest son of Thomas Butler, Viscount Thurles and of Elizabeth, Lady Thurles, daughter of Sir John Pointz of Iron Acton in Gloucestershire and his second wife Elizabeth Sydenham. His sister Elizabeth married Nicholas Purcell, 13th Baron of Loughmoe. James's paternal grandfather was Walter Butler, 11th Earl of Ormond. He was born at Clerkenwell, London, 19 October 1610, in the house of his maternal grandfather, Sir John Poyntz. Shortly after his birth, his parents returned to Ireland. The Butlers of Ormonde were an Old English dynasty who had dominated the southeast of Ireland since the Middle Ages.

Upon the shipwreck and death of his father in 1619, the lad was by courtesy styled Viscount Thurles. The year following that disaster, his mother brought him back to England, and placed him, then nine years of age, at school with a Catholic gentleman at Finchley — this doubtless through the influence of his grandfather, the 11th Earl. It was not long before James I of England, anxious that the heir of the Butlers should be brought up a Protestant, placed him at Lambeth, under the care of George Abbot, archbishop of Canterbury. The Ormond estates being under sequestration (as noted in the life of the 11th Earl) the young Lord had but £40 a year for his own and his servant's clothing and expenses. He appears to have been entirely neglected by the Archbishop — "he was not instructed even in humanity, nor so much as taught to understand Latin".

At Christmas 1629, Ormand married Elizabeth the only child and heiress of Sir Richard Preston, Earl of Desmond. They had at least 7 children, of whom three of his sons and two daughters survived into adulthood.

Ormonde's active career began in 1633 with the appointment as head of government in Ireland of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, by whom Ormonde was treated with great favour. Writing to Charles I, Wentworth described Ormonde as "young, but take it from me, a very staid head". Ormonde became Wentworth's chief friend and supporter. Wentworth planned large scale confiscations of Catholic-owned land, both to raise money for the crown and to break the political power of the Irish Catholic gentry, a policy which Ormonde supported. Yet, it infuriated his relatives, and drove many of them into opposition to Wentworth and ultimately into armed rebellion. In 1640, with Wentworth having been recalled to attend to the Second Bishops' War in England, Ormonde was made commander-in-chief of the forces in Ireland. The opposition to Wentworth ultimately aided impeachment of the Earl by the English Parliament, and his eventual execution in May 1641.

The eldest of these, Thomas, Earl of Ossory (1634 – 1680) predeceased him, his eldest son (that is to say James Butler's grandchild) succeeded as 2nd Duke of Ormonde (1665 – 1745). The other two sons, Richard, created earl of Arran, and John, created earl of Gowran, both died without male issue, and the male descent of the 1st Duke becoming extinct in the person of Charles, 3rd Duke of Ormonde, the earldom subsequently reverted to the cadet descendants of Walter, 11th earl of Ormonde.

On the outbreak of the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Ormonde found himself in command of government forces based in Dublin. Most of the country was taken by the Catholic rebels, who included Ormonde's Butler relatives. However Ormonde's bonds of kinship were not entirely severed. His wife and children were escorted from Kilkenny to Dublin under the order of the rebel leader Richard Butler, 3rd Viscount Mountgarret, another member of the Butler dynasty. In spring 1642 Mountgarret and Ormonde were the commanders of the opposing forces at the battle of Kilrush, with Ormonde's side winning.

In spring 1642 the Irish Catholics formed their own government, the Catholic Confederation, with its capital at Kilkenny, and began to raise their own regular troops, more organized and capable than the irregular militia of the 1641 rebellion. Also in early 1642 the king sent in troop reinforcements from England and Scotland. The Irish Confederate War was under-way. Ormonde mounted several expeditions from Dublin in 1642, that cleared the area around Dublin of Confederate forces. He secured control of the area historically known as the Pale, and re-supplied some outlying garrisons, without serious contest. The Lords Justices, who suspected him because he was related to many of the Confederate Leaders, recalled him from command, after he had succeeded in lifting the siege of Drogheda in March 1642. In April he relieved the royalist garrisons at Naas, Athy and Maryborough, and on his return to Dublin he won the Battle of Kilrush against a larger force. He received the public thanks of the English Parliament and a monetary reward, and in September 1642 was put in command with a commission direct from the king.

Soon afterwards, in November 1643, by the king's orders, Ormonde dispatched a body of his troops into England to fight on the Royalist side in the Civil War, estimated at 4,000 troops, half of whom were sent from Cork. In November 1643 the king appointed Ormonde as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland—head of the Irish government executive, in other words. For the previous two years the occupant of this post had not set foot in Ireland. Ormonde's assigned mission was to prevent the king's Parliamentarian enemies from being reinforced from Ireland, and to aim to deliver more troops to fight for the Royalist side in England. To these ends, he had instructions to do all in his power to keep the Scottish Covenanter army in the north of Ireland occupied. He was also given the king's authority to negotiate a Treaty with the Catholic Confederation which could allow their troops to be redirected against the Parliamentarians.

In 1644, he assisted Randall Macdonnell, 1st Marquess of Antrim in mounting an Irish Confederate expedition into Scotland. The force, led by Alasdair MacColla was sent to help the Scottish Royalists and sparked off a civil war in Scotland (1644–45). This turned out to be the only intervention of Irish Catholic troops in Britain during the Civil Wars.

Ormonde also served as the sixth Chancellor of Trinity College, Dublin between 1645 and 1688, although he was in exile for the first fifteen years of his tenure.

Ormonde attended King Charles during August and October 1647 at Hampton Court Palace, but in March 1648, in order to avoid arrest by the parliament, he joined the Queen and the Prince of Wales at Paris. In September of the same year, the pope's nuncio having been expelled, and affairs otherwise looking favourable, he returned to Ireland to endeavour to unite all parties for the king.

However, despite controlling almost all of Ireland before August 1649, Ormonde was unable to prevent the conquest of Ireland by Cromwell in 1649-50. Ormonde tried to re-take Dublin by laying siege to the city in the summer of 1649, but was routed at the Battle of Rathmines. Subsequently, he tried to halt Cromwell by holding a line of fortified towns across the country. However, the New Model Army took them one after the other, beginning with the Siege of Drogheda in September 1649.

Ormonde lost most of the English and Protestant Royalist troops under his command when they mutinied, and went over to Cromwell in May 1650. This left him with only the Irish Catholic forces, who distrusted him greatly. Ormonde was ousted from his command in late 1650 and he returned to France in December 1650. A synod held in at the Augustinian abbey in Jamestown, County Leitrim, repudiated the Duke and excommunicated his followers. In Cromwell's Act of Settlement 1652, all of Ormonde's lands in Ireland were confiscated and he was excepted from the pardon given to those Royalists who had surrendered by that date.

Ormonde, though desperately short of money, was in constant attendance on Charles II and the Queen Mother in Paris, and accompanied the former to Aix and Cologne when expelled from France by the terms of Mazarin's treaty with Cromwell in 1655. In April 1656 Ormonde was one of two signatories who agreed the Treaty of Brussels, securing an alliance for the Royalists with the Spanish court. In 1658, he went disguised, and at great risk, on a secret mission into England to gain trustworthy intelligence as to the chances of an uprising. He attended the king at Fuenterrabia in 1659, and had an interview with Mazarin and was actively engaged in the secret transactions immediately preceding the Restoration. Relations between Ormonde and the Queen Mother became increasingly strained; when she remarked that "if she had been trusted the King had now been in England", Ormonde retorted that "if she had never been trusted the King had never been out of England".

His heart was in his government, and he vehemently opposed the Importation Act 1667 prohibiting the importation of Irish cattle, which struck so fatal a blow at Irish trade; and retaliated by prohibiting the import into Ireland of Scottish commodities, and obtained leave to trade with foreign countries. He encouraged Irish manufactures and learning to the utmost, and it was to his efforts that the Irish College of Physicians owes its incorporation.

He had billeted Soldiers on civilians, and had executed martial law. He was threatened by Buckingham with impeachment. In March 1669, Ormonde was removed from the government of Ireland and from the committee for Irish affairs. He made no complaint, insisted that his sons and others over whom he had influence should retain their posts, and continued to fulfil the duties of his other offices, while his character and services were recognized in his election as Chancellor of the University of Oxford on 4 August 1669.

In his estates in Carrick-on-Suir in County Tipperary, he was responsible for establishing the woollen industry in the town in 1670.

In 1671 Ormonde successfully opposed Richard Talbot's attempt to upset the Act of Settlement 1662. In 1673, he again visited Ireland, returned to London in 1675 to give advice to Charles on affairs in parliament, and in 1677 was again restored to favour and reappointed to the lord lieutenancy. On his arrival in Ireland he occupied himself in placing the revenue and the army upon a proper footing. Upon the outbreak of the disturbances caused by the Popish Plot (1678) in England, Ormonde at once took steps towards rendering the Roman Catholics, who were in the proportion of 15 to 1, powerless; and the mildness and moderation of his measures served as the ground of an attack upon him in England led by Shaftesbury, from which he was defended with great spirit by his own son Lord Ossory. While wary of defending Oliver Plunkett publicly, in private he denounced the obvious falsity of the charges against him - of the informers who claimed that Plunkett had hired them to kill the King he wrote that "no schoolboy would have trusted them to rob an orchard".

The anonymous author of Ormond's biography in the Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.) the wrote that with him disappeared the greatest and grandest figure of the times, and that Ormond's splendid qualities were expressed with some felicity in verses written on welcoming his return to Ireland and printed in 1682:

Subsequently, Ormonde lived in retirement at Cornbury in Oxfordshire, a house lent to him by Lord Clarendon, but emerged in 1687 to offer opposition at the board of the Charterhouse to James's attempt to assume the dispensing power and force upon the institution a Roman Catholic candidate without taking the oaths. Ormonde also refused the king his support in the question of the Indulgence; James, to his credit, refused to take away his offices, and continued to hold him in respect and favour to the last. Despite his long Service to Ireland he admitted that he had no wish to spend his last years there.

Ormonde died on 21 July 1688 at Kingston Lacy, Dorset, not having, as he rejoiced to know, "outlived his intellectuals". Ormonde was buried in Westminster Abbey on 1 August 1688.

Ormonde was faced with a difficult task in reconciling all the different factions in Ireland. The Old (native) Irish and Catholic Irish of English descent ("Old English") were represented in Confederate Ireland—essentially an independent Catholic government based in Kilkenny—who wanted to come to terms with King Charles I of England in return for religious toleration and self-government. On the other side, any concession that Ormonde made to the Confederates weakened his support among English and Scottish Protestants in Ireland. Ormonde's negotiations with the Confederates were therefore tortuous, even though many of the Confederate Leaders were his relatives or friends.