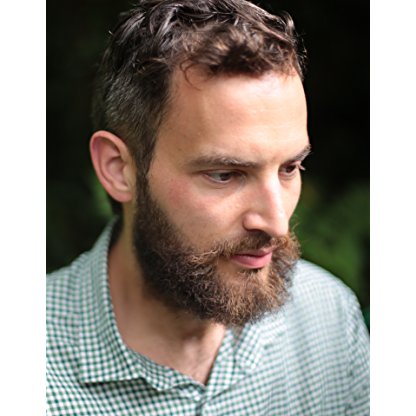

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Camera Department, Cinematographer, Producer |

| Birth Day | October 21, 1786 |

| Age | 233 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 2 March 1854(1854-03-02) (aged 67)\nArborfield Hall, near Reading, Berkshire, England |

| Birth Sign | Aquarius |

| Known for | Chief attendant of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn; comptroller to the early household of Queen Victoria |

| Title | Baronet |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Fisher |

| Children | Sir Edward Conroy, 2nd Baronet Victoire Conroy |

Net worth

John Conroy, a renowned figure in the field of camera department, cinematography, and production, is projected to possess a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M by the year 2024. With a successful career spanning many years, Conroy has established himself as a prominent figure in the industry. Born in the year 1786, his expertise and talent in the camera department have garnered him significant recognition and substantial financial success. With his diverse skills as both a cinematographer and producer, Conroy has undoubtedly left an indelible mark on the world of film and photography.

Famous Quotes:

Conroy goes not to Court, the reason's plain

King John has played his part and ceased to reign.

Biography/Timeline

Conroy was born on 21 October 1786 in Maes-y-castell, Caerhun, Caernarvonshire, Wales. He was one of six children born to John Ponsonby Conroy, Esq., and Margaret Wilson, both native to Ireland. His father was a barrister and the younger Conroy was privately educated in Dublin. On 8 September 1803, he was commissioned in the Royal Artillery as a Second Lieutenant and was promoted to first lieutenant on 12 September. In 1805, Conroy enrolled in the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. He made his career during the Napoleonic Wars, though his ability to avoid battle attracted disdain from other officers. Conroy did not participate in the Peninsular War or the Waterloo Campaign.

Further advancement of rank was facilitated with Conroy's marriage to Elizabeth Fisher on 26 December 1808 in Dublin, though not as far as Conroy felt he deserved. Elizabeth was the daughter of Colonel (later Major-General) Benjamin Fisher and Conroy served under him in Ireland and England while performing various administrative duties. Conroy was promoted to Second Captain on 13 March 1811 and appointed adjutant in the Corps of Artillery Drivers on 11 March 1817.

Through the connection of his wife's uncle, Conroy came to the attention of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, the fourth son of King George III. Conroy was appointed as an equerry in 1817, shortly before the Duke's marriage to Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. An efficient organiser, Conroy's planning ensured the Duke and Duchess' speedy return to England in time for the birth of their first child. The child was Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent, later Queen Victoria.

While Kent had promised Conroy military advancement, he was still a captain by the time of the Duke's death in 1820. Conroy was named an executor of the Duke's will, though he was unsuccessful in persuading the dying man to name him Victoria's guardian. Aware that he needed to find another source of revenue quickly, Conroy offered his services as comptroller to the now-widowed Duchess of Kent and her infant daughter. He retired from military Service on half-pay in 1822.

In 1827, the Duke of York died, making the Duke of Clarence heir presumptive and Victoria second-in-line to the throne. Conroy complained that the Princess should not be surrounded by commoners, leading King George IV to appoint Conroy a Knight Commander of the Hanoverian Order and a Knight Bachelor that year. The Duchess and Conroy continued to be unpopular with the royal family and, in 1829, the Duke of Cumberland spread rumours that they were lovers in an attempt to discredit them. The Duke of Clarence referred to Conroy as "King John", while the Duchess of Clarence wrote to the Duchess of Kent to advise that she was increasingly isolating herself from the royal family and that she must not grant Conroy too much power.

The Duke of Clarence became King william IV in 1830, by which point Conroy felt very confident of his position; his control of the household was secure. The Duchess prevented her daughter from attending William's coronation out of a disagreement of precedence, a decision attributed by the Duke of Wellington to Conroy. By then, it had become clear to Victoria that she would succeed to the throne. The new king and queen attempted to gain custody of their niece, but Conroy quickly replied that Victoria could not be "tainted" by the moral atmosphere at court. Conroy solidified the stance that mother and daughter could not be separated, and continued to promote the Duchess' virtue as a fit regent.

As King william intensely disliked the Duchess and Conroy, he vowed to wait until Victoria came of age to die simply to keep them from a regency. In 1831, the year of William's coronation, Conroy and the Duchess embarked on a series of royal tours with Victoria to expose her to the people and solidify their status as potential regents. On one trip Conroy was awarded an honorary degree by the University of Oxford. Their efforts were ultimately successful and, in November 1831, it was declared that the Duchess would be sole regent in the event of Victoria's young queenship, while Conroy could claim to be the closest adviser to the Duchess and her daughter.

After Conroy's departure from Victoria's Service in 1837, a popular song read:

One of Victoria's first acts as queen was to dismiss Conroy from her own household, though she could not dismiss him from her mother's. Queen Victoria, as an unmarried young woman, was still expected to live with her mother, but she relegated the Duchess and Conroy to remote apartments at Buckingham Palace, cutting off personal contact with them. The Duchess unsuccessfully insisted that Conroy and his family be allowed at court; Victoria disagreed, saying: "I thought you would not expect me to invite Sir John Conroy after his conduct towards me for some years past." In 1839, the Duke of Wellington convinced Conroy to leave the Duchess's household and take his family to the Continent in effective exile. The Times reported that he no longer had official duties, though they were unsure if he had resigned or been dismissed. That year rumours abounded that Lady Flora Hastings, whose abdomen had grown large, was pregnant by Conroy. A subsequent medical investigation concluded that Lady Flora was a virgin and she died from liver cancer several months later. This scandal, in tandem with the Bedchamber Crisis, damaged Victoria's reputation.

Princess Sophia's substantial income, provided from the civil list, had allowed Conroy to enjoy a wealthy lifestyle. The Princess died in 1848, leaving only £1,607 19s 7d in her bank accounts despite a lifestyle of savings and low expenses. The Duke of Cambridge and the Duchess of Gloucester had a Lawyer write to Conroy demanding that he account for the rest of their sister Sophia's funds, but Conroy simply ignored it. According to Flora Fraser, the most recent biographer of George III's daughters, Princess Sophia had in fact personally spent huge sums on Conroy, including heavy contributions to the purchase prices of his residences and supporting his family in a style he judged appropriate to their position. Conroy ultimately received £148,000 in gifts and money from Sophia.

In 1850, the Duchess of Kent's new comptroller, Sir George Couper, studied the old accounts. He found huge discrepancies. No records for her household or personal expenses had been kept after 1829. There was also no record of nearly £50,000 the Duchess had received from her brother, Leopold, nor of an additional £10,000 from william IV.

Conroy's relationship with the Duchess was the subject of much speculation both before and after his death in 1854. When the Duke of Wellington was asked if the Duchess and Conroy were lovers, he replied that he "supposed so". In August 1829, Wellington reported to court diarist Charles Greville that Victoria, then ten years old, had caught Conroy and her mother engaged in "some familiarities". Victoria told her governess, Baroness Lehzen, who in turn told Madame de Spaeth, one of the Duchess's ladies-in-waiting. De Spaeth confronted the Duchess about the relationship and was immediately dismissed. All of this was recorded by Greville; his subsequent diary entry has led to the persistent belief that the Duchess and Conroy were lovers. Later, as an aged Queen, Victoria was aghast to discover that many people did indeed believe that her mother and Conroy were intimate and stated that the Duchess' piety would have prevented this.

During Victoria's lifetime and after her death in 1901, there have been rumours that Conroy or someone else, and not the Duke of Kent, was her biological father. Historians have continued to debate the accuracy and validity of these claims. In his 2003 work The Victorians, biographer A. N. Wilson suggests that Victoria was not actually descended from George III because several of her descendants had haemophilia, which was unknown among her recognised ancestors. Haemophilia is a genetic disease that impairs the body's ability to control blood clotting, which is used to stop bleeding when a blood vessel is broken; it is carried in the female line but the symptoms manifest mostly in males. Wilson proposes that the Duchess of Kent took a lover (not necessarily Conroy) to ensure that a Coburg would sit on the British throne.

Conroy has been portrayed numerous times in film and television. Herbert Wilcox's Victoria the Great (1937) depicted Conroy as a "smarmy character" who is not well developed in the film. The baronet was played by Stefan Skodler in 1954's The Story of Vickie, and Herbert Hübner in Mädchenjahre einer Königin (1936). Patrick Malahide played Conroy in Victoria & Albert, a 2001 TV miniseries that depicted Victoria's early influences. English actor Mark Strong played him in the 2009 film The Young Victoria. The film depicts Conroy as a maniacal controlling pseudo-father to the young Victoria during the year preceding her accession even going so far as depicting him assaulting the Princess twice. The film goes on to depict Conroy's expulsion from Queen Victoria's household.

Conroy also appears in numerous historical fiction novels about Queen Victoria. Writing under the pen names Jean Plaidy and Eleanor Burford, author Eleanor Hibbert published a series of novels in the 1970s and 1980s, which included The Captive of Kensington Palace (1972), The Queen and Lord M (1973) and Victoria Victorious: The Story of Queen Victoria (1985). A. E. Moorat released the parody novel Queen Victoria: Demon Hunter in 2009.

Described in his own lifetime as a "ridiculous fellow", Conroy has not been the recipient of much recent positive historical opinion. Twentieth-century Historian Christopher Hibbert writes that Conroy was a "good-looking man of insinuating charm, tall, imposing, vain, clever, unscrupulous, plausible and of limitless ambition." For her part, 21st-century Historian Gillian Gill describes Conroy as "a career adventurer, expert manipulator and domestic martinet" who came to England with "small means, some ability and mighty ambition." In 2004, Elizabeth Longford wrote that Conroy "was not the arch-villain Victoria painted, but the victim of his own inordinate ambition."