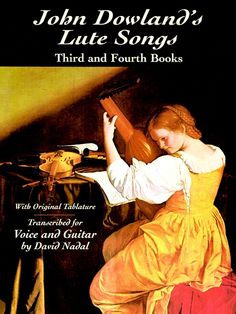

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Singer, Lutenist and Composer |

| Birth Place | London, British |

| Died On | February 20, 1626 |

Net worth: $950,000 (2024)

John Dowland, a renowned singer, lutenist, and composer in British history, is estimated to have a net worth of $950,000 in 2024. Dowland, who lived during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, was known for his exceptional musical talents and contributions to the English Renaissance period. His works, which encompassed melancholic and introspective themes, earned him great acclaim and popularity during his time. With his exceptional skills and remarkable compositions, it is no surprise that Dowland has managed to accumulate a considerable fortune, solidifying his legacy as an influential figure in the world of music.

Famous Quotes:

Flow my tears, fall from your springs,

Exil'd for ever let me mourn;

Where night's black bird her sad infamy sings,

There let me live forlorn.— John Dowland

Biography/Timeline

Very little is known of John Dowland's early life, but it is generally thought he was born in London. Irish Historian W. H. Grattan Flood claimed that he was born in Dalkey, near Dublin, but no corroborating evidence has ever been found either for that statement or for Thomas Fuller's claim that he was born in Westminster. There is however one very clear piece of evidence pointing to Dublin as his place of origin: he dedicated the song "From Silent Night" to 'my loving countryman Mr. John Forster the younger, merchant of Dublin in Ireland'. The Forsters were a prominent Dublin family at the time, providing several Lord Mayors to the city. In 1580 Dowland went to Paris, where he was in Service to Sir Henry Cobham, the ambassador to the French court, and his successor, Sir Edward Stafford. He became a Roman Catholic at this time. In 1584, Dowland moved back to England where he was married. In 1588 he was admitted Mus. Bac. from Christ Church, Oxford. In 1594 a vacancy for a lutenist came up at the English court, but Dowland's application was unsuccessful – he claimed his religion led to his not being offered a post at Elizabeth I's Protestant court. However, his conversion was not publicised, and being Catholic did not prevent some other important Musicians (such as william Byrd) from having a court career in England.

Published by Thomas Est in 1592, The Whole Booke of Psalmes contained works by 10 composers, including 6 pieces by Dowland.

The New Booke of Tabliture was published by william Barley in 1596. It contains seven solo lute pieces by Dowland.

Dowland published his The First Booke of Songes or Ayres in London in 1597. It was one of the most influential and important musical publications of the history of the lute. This collection of lute-songs was set out in a way that allows performance by a soloist with lute accompaniment or various combinations of Singers and instrumentalists.

Richard Barnfield, Dowland's contemporary, refers to him in poem VIII of The Passionate Pilgrim (1598), a Shakespearean sonnet:

Dowland published The Second Booke of Songs or Ayres, in 1600.

The Third and Last Booke of Songs or Aires was published in 1603.

The Lachrimae, or Seaven Teares was published in 1604. It contains the seven pavans of Lachrimae itself and 14 others, including the famous Semper Dowland semper Dolens.

Dowland published a translation of the Micrologus of Andreas Ornithoparcus in 1609, originally printed in Leipzig in 1517, described as "a rather stiff and medieval treatise, but nonetheless occasionally entertaining".

A Musicall Banquet was published by Dowland's son, Robert Dowland, in 1610. It contains three songs by John Dowland.

Dowland's last work A Pilgrimes Solace, was published in 1612, and seems to have been conceived more as a collection of contrapuntal music than as solo works.

From 1598 Dowland worked at the court of Christian IV of Denmark, though he continued to publish in London. King Christian was very interested in music and paid Dowland astronomical sums; his salary was 500 daler a year, making him one of the highest-paid servants of the Danish court. Though Dowland was highly regarded by King Christian, he was not the ideal servant, often overstaying his leave when he went to England on publishing Business or for other reasons. Dowland was dismissed in 1606 and returned to England; in early 1612 he secured a post as one of James I's lutenists. There are few compositions dating from the moment of his royal appointment until his death in London in 1626. While the date of his death is not known, "Dowland's last payment from the court was on 20 January 1626, and he was buried at St Ann's, Blackfriars, London, on 20 February 1626."

One of the first 20th-century Musicians who successfully helped reclaim Dowland from the history books was the singer-songwriter Frederick Keel. Keel included fifteen Dowland pieces in his two sets of Elizabethan love songs published in 1909 and 1913, which achieved popularity in their day. These free arrangements for piano and low or high voice were intended to fit the tastes and musical practices associated with art songs of the time.

In 1935, Australian-born Composer Percy Grainger, who also had a deep interest in music made before Bach, arranged Dowland's Now, O now I needs must part for piano. Some years later, in 1953, Grainger wrote a work titled Bell Piece (Ramble on John Dowland's 'Now, O now I needs must part'), which was a version scored for voice and wind band, based on his previously mentioned transcription.

In 1951 Alfred Deller, the famous counter-tenor (1912–1979), recorded songs by Dowland, Thomas Campion, and Philip Rosseter with the label HMV (His Master's Voice) HMV C.4178 and another HMV C.4236 of Dowland's "Flow my Tears". In 1977, Harmonia Mundi also published two records of Deller singing Dowland's Lute songs (HM 244&245-H244/246).

Dowland's music became part of the repertoire of the early music revival with lutenist Julian Bream and tenor Peter Pears, and later with Christopher Hogwood and David Munrow and the Early Music Consort in the late 1960s and later with the Academy of Ancient Music from the early 1970s.

Dowland's song, "Come Heavy Sleepe, the Image of True Death", was the inspiration for Benjamin Britten's Nocturnal after John Dowland, written in 1963 for the Guitarist Julian Bream. This work consists of eight variations, all based on musical themes drawn from the song or its lute accompaniment, finally resolving into a guitar setting of the song itself.

Jan Akkerman, Guitarist of the Dutch progressive rock band Focus, recorded "Tabernakel" in 1973 (though released in 1974), an album of John Dowland songs and some original material, performed on lute.

The Collected Lute Music of John Dowland, with lute tablature and keyboard notation, was transcribed and edited by Diana Poulton and Basil Lam, Faber Music Limited, London 1974.

Nigel North recorded Dowland's complete works for solo lute on four CDs between 2004 and 2007, on Naxos records.

In October 2006, Sting, who says he has been fascinated by the music of John Dowland for 25 years, released an album featuring Dowland's songs titled Songs from the Labyrinth, on Deutsche Grammophon, in collaboration with Edin Karamazov on lute and archlute. They described their treatment of Dowland's work in a Great Performances appearance. To give some idea of the tone and intrigues of life in late Elizabethan England, Sting also recites throughout the album portions of a 1593 letter written by Dowland to Sir Robert Cecil. The letter describes Dowland's travels to various points of Western Europe, then breaks into a detailed account of his activities in Italy, along with a heartfelt denial of the charges of treason whispered against him by unknown persons. Dowland most likely was suspected of this for travelling to the courts of various Catholic monarchs and accepting payment from them greater than what a musician of the time would normally have received for performing.

John Dowland: Complete Solo Galliards for Renaissance Lute or Guitar was transcribed and edited with performance suggestions, new divisions (or variations) and transposition for 6-stringed instruments by Ben Salfield, Peacock Press, UK, 2014.