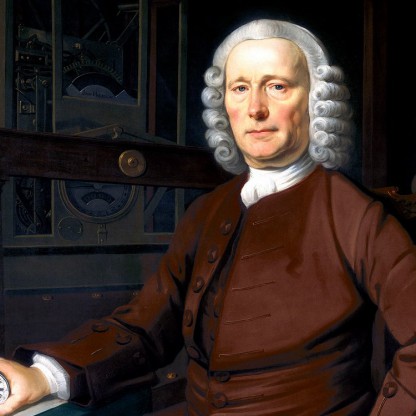

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Birth Year | 1693 |

| Birth Place | Foulby, British |

| Age | 326 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 24 March 1776(1776-03-24) (aged 82)\nLondon, England |

| Birth Sign | Taurus |

| Residence | Red Lion Square |

| Known for | Marine chronometer |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1749) |

| Fields | Horology |

Net worth: $9 Million (2024)

John Harrison, popularly known as Miscellaneous in the British music industry, is projected to have a net worth of $9 million by 2024. Over the years, he has built a successful career as a musician and artist, making significant contributions to the British music scene. With his unique style and talent, John has amassed a dedicated fanbase and achieved notable commercial success, translating into considerable financial earnings. As his net worth continues to grow, John Harrison's success serves as a testament to his hard work, passion, and impact in the music industry.

Biography/Timeline

Around 1700, the Harrison family moved to the Lincolnshire village of Barrow upon Humber. Following his father's trade as a carpenter, Harrison built and repaired clocks in his spare time. Legend has it that at the age of six, while in bed with smallpox, he was given a watch to amuse himself and he spent hours listening to it and studying its moving parts.

His solution revolutionized navigation and greatly increased the safety of long-distance sea travel. The Problem he solved was considered so important following the Scilly naval disaster of 1707 that the British Parliament offered financial rewards of up to £20,000 (equivalent to £2.89 million today) under the 1714 Longitude Act. Harrison came 39th in the BBC's 2002 public poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.

Harrison built his first longcase clock in 1713, at the age of 20. The mechanism was made entirely of wood. Three of Harrison's early wooden clocks have survived: the first (1713) is in the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers' collection previously in the Guildhall in London, and since 2015 on display in the Science Museum. The second (1715) is also in the Science Museum in London; and the third (1717) is at Nostell Priory in Yorkshire, the face bearing the inscription "John Harrison Barrow". The Nostell Example, in the billiards room of this stately home, has a Victorian outer case, which has small glass windows on each side of the movement so that the wooden workings may be inspected.

In 1716, Sully presented his first Montre de la Mer to the French Académie des Sciences and in 1726 he published Une Horloge inventée et executée par M. Sulli.

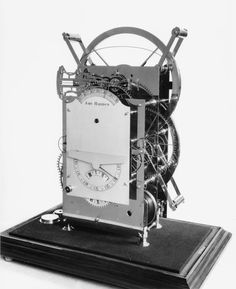

In the 1720s, the English clockmaker Henry Sully invented a marine clock that was designed to determine longitude: this was in the form of a clock with a large balance wheel that was vertically mounted on friction rollers and impulsed by a frictional rest Debaufre type escapement. Very unconventionally, the balance oscillations were controlled by a weight at the end of a pivoted horizontal lever attached to the balance by a cord. This solution avoided temperature error due to thermal expansion, a Problem which affects steel balance springs. Sully's clock only kept accurate time in calm weather, because the balance oscillations were affected by the pitching and rolling of the ship. However his clocks were amongst the first serious attempts to find longitude in this way. Harrison's machines, though much larger, are of similar layout: H3 has a vertically mounted balance wheel and is linked to another wheel of the same size, an arrangement that eliminates problems arising from the ship's motion.

In 1730, Harrison designed a marine clock to compete for the Longitude Prize and travelled to London, seeking financial assistance. He presented his ideas to Edmond Halley, the Astronomer Royal, who in turn referred him to George Graham, the country's foremost clockmaker. Graham must have been impressed by Harrison's ideas, for he loaned him money to build a model of his "Sea clock". As the clock was an attempt to make a seagoing version of his wooden pendulum clocks, which performed exceptionally well, he used wooden wheels, roller pinions and a version of the 'grasshopper' escapement. Instead of a pendulum, he used two dumbbell balances, linked together.

It took Harrison five years to build his first sea clock (or H1). He demonstrated it to members of the Royal Society who spoke on his behalf to the Board of Longitude. The clock was the first proposal that the Board considered to be worthy of a sea trial. In 1736, Harrison sailed to Lisbon on HMS Centurion under the command of Captain George Proctor and returned on HMS Orford after Proctor died at Lisbon on 4 October 1736. The clock lost time on the outward voyage. However, it performed well on the return trip: both the captain and the sailing master of the Orford praised the design. The master noted that his own calculations had placed the ship sixty miles east of its true landfall which had been correctly predicted by Harrison using H1.

This was not the transatlantic voyage demanded by the Board of Longitude, but the Board was impressed enough to grant Harrison £500 for further development. Harrison had moved to London by 1737 and went on to develop H2, a more compact and rugged version. In 1741, after three years of building and two of on-land testing, H2 was ready, but by then Britain was at war with Spain in the War of Austrian Succession and the mechanism was deemed too important to risk falling into Spanish hands. In any event, Harrison suddenly abandoned all work on this second machine when he discovered a serious design flaw in the concept of the bar balances. He had not recognized that the period of oscillation of the bar balances could be affected by the yawing action of the ship (when the ship turned such as 'coming about' while tacking). It was this that led him to adopt circular balances in the Third Sea Clock (H3).

After steadfastly pursuing various methods during thirty years of experimentation, Harrison found to his surprise that some of the watches made by Graham's successor Thomas Mudge kept time just as accurately as his huge sea clocks. It is possible that Mudge was able to do this after the early 1740s thanks to the availability of the new "Huntsman" or "Crucible" steel produced by Benjamin Huntsman sometime in the early 1740s which enabled harder pinions but more importantly, a tougher and more highly polished cylinder escapement to be produced. Harrison then realized that a mere watch after all could be made accurate enough for the task and was a far more practical proposition for use as a marine timekeeper. He proceeded to redesign the concept of the watch as a timekeeping device, basing his design on sound scientific principles.

He had already in the early 1750s designed a precision watch for his own personal use, which was made for him by the watchmaker John Jefferys c. 1752–1753. This watch incorporated a novel frictional rest escapement and was not only the first to have a compensation for temperature variations but also contained the first miniature 'going fusee' of Harrison's design which enabled the watch to continue running whilst being wound. These features led to the very successful performance of the "Jefferys" watch, which Harrison incorporated into the design of two new timekeepers which he proposed to build. These were in the form of a large watch and another of a smaller size but of similar pattern. However, only the larger No. 1 (or "H4" as it is sometimes called) watch appears ever to have been finished. (See the reference to "H6" below) Aided by some of London's finest workmen, he proceeded to design and make the world's first successful marine timekeeper that allowed a navigator to accurately assess his ship's position in longitude. Importantly, Harrison showed everyone that it could be done by using a watch to calculate longitude. This was to be Harrison's masterpiece – an instrument of beauty, resembling an oversized pocket watch from the period. It is engraved with Harrison's signature, marked Number 1 and dated AD 1759.

This first watch took six years to construct, following which the Board of Longitude determined to trial it on a voyage from Portsmouth to Kingston, Jamaica. For this purpose it was placed aboard the 50-gun HMS Deptford, which set sail from Portsmouth on 18 November 1761. Harrison, by then 68 years old, sent it on this transatlantic trial in the care of his son, william. The watch was tested before departure by Robertson, Master of the Academy at Portsmouth, who reported that on 6 November 1761 at noon it was 3 seconds slow, having lost 24 seconds in 9 days on mean solar time. The daily rate of the watch was therefore fixed as losing 24/9 seconds per day.

When Deptford reached its destination, after correction for the initial error of 3 seconds and accumulated loss of 3 minutes 36.5 seconds at the daily rate over the 81 days and 5 hours of the voyage, the watch was found to be 5 seconds slow compared to the known longitude of Kingston, corresponding to an error in longitude of 1.25 minutes, or approximately one nautical mile. Harrison returned aboard the 14-gun HMS Merlin, reaching England on 26 March 1762 to report the successful outcome of the experiment. Harrison senior thereupon waited for the £20,000 prize, but the Board were persuaded that the accuracy could have been just luck and demanded another trial. The board were also not convinced that a timekeeper which took six years to construct met the test of practicality required by the Longitude Act. The Harrisons were outraged and demanded their prize, a matter that eventually worked its way to Parliament, which offered £5,000 for the design. The Harrisons refused but were eventually obliged to make another trip to Bridgetown on the island of Barbados to settle the matter.

In total, Harrison received £23,065 for his work on chronometers. He received £4,315 in increments from the Board of Longitude for his work, £10,000 as an interim payment for H4 in 1765 and £8,750 from Parliament in 1773. This gave him a reasonable income for most of his life (equivalent to roughly £45,000 per year in 2007, though all his costs, such as materials and subcontracting work to other horologists, had to come out of this). He became the equivalent of a multi-millionaire (in today's terms) in the final decade of his life.

Harrison began working on his second 'sea watch' (H5) while testing was conducted on the first, which Harrison felt was being held hostage by the Board. After three years he had had enough; Harrison felt "extremely ill used by the gentlemen who I might have expected better treatment from" and decided to enlist the aid of King George III. He obtained an audience with the King, who was extremely annoyed with the Board. King George tested the watch No.2 (H5) himself at the palace and after ten weeks of daily observations between May and July in 1772, found it to be accurate to within one third of one second per day. King George then advised Harrison to petition Parliament for the full prize after threatening to appear in person to dress them down. Finally in 1773, when he was 80 years old, Harrison received a monetary award in the amount of £8,750 from Parliament for his achievements, but he never received the official award (which was never awarded to anyone). He was to survive for just three more years.

Harrison died on March 24, 1776 at the age of eighty-two, just shy of his eighty-third birthday. He was buried in the graveyard of St John's Church, Hampstead, in north London, along with his second wife Elizabeth and later their son william. His tomb was restored in 1879 by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, even though Harrison had never been a member of the Company.

The more accurate Harrison timekeeping device led to the much-needed precise calculation of longitude, making the device a fundamental key to the modern age. Following Harrison, the marine timekeeper was reinvented yet again by John Arnold who while basing his design on Harrison's most important principles, at the same time simplified it enough for him to produce equally accurate but far less costly marine chronometers in quantity from around 1783. Nonetheless, for many years even towards the end of the 18th century, chronometers were expensive rarities, as their adoption and use proceeded slowly due to the high expense of precision Manufacturing. The expiry of Arnold's patents at the end of the 1790s enabled many other watchmakers including Thomas Earnshaw to produce chronometers in greater quantities at less cost even than those of Arnold. By the early 19th century, navigation at sea without one was considered unwise to unthinkable. Using a chronometer to aid navigation simply saved lives and ships—the insurance industry, self-interest, and Common sense did the rest in making the device a universal tool of maritime trade.

Captain James Cook used K1, a copy of H4, on his second and third voyages, having used the lunar distance method on his first voyage. K1 was made by Larcum Kendall, who had been apprenticed to John Jefferys. Cook's log is full of praise for the watch and the charts of the southern Pacific Ocean he made with its use were remarkably accurate. K2 was loaned to Lieutenant william Bligh, commander of HMS Bounty but it was retained by Fletcher Christian following the infamous mutiny. It was not recovered from Pitcairn Island until 1840, and then passed through several hands before reaching the National Maritime Museum in London.

The timepieces were in a highly decrepit state and Gould spent many years documenting, repairing and restoring them, without compensation for his efforts. Gould was the first to designate the timepieces from H1 to H5, initially calling them No.1 to No.5. Unfortunately, Gould made modifications and repairs that would not pass today's standards of good museum conservation practice, although most Harrison scholars give Gould credit for having ensured that the historical artifacts survived as working mechanisms to the present time. Gould wrote The Marine Chronometer published in 1923, which covered the history of chronometers from the Middle Ages through to the 1920s, and which included detailed descriptions of Harrison's work and the subsequent evolution of the chronometer. The book remains the authoritative work on the marine chronometer.

In 1995, inspired by a Harvard University symposium on the longitude Problem organized by the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Dava Sobel wrote a book on Harrison's work. Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time became the first popular bestseller on the subject of horology. The Illustrated Longitude, in which Sobel's text was accompanied by 180 images selected by william J. H. Andrewes, appeared in 1998. The book was dramatised for UK television by Charles Sturridge in a Granada Productions film for Channel 4 in 1999, under the title Longitude. It was broadcast in the US later that same year by co-producer A&E. The production starred Michael Gambon as Harrison and Jeremy Irons as Gould. Sobel's book was also the basis for a PBS NOVA episode entitled Lost at Sea: The Search for Longitude.

Harrison's marine time-keepers were an essential part of the plot in the 1996 Christmas special of long-running British sitcom Only Fools And Horses, entitled "Time On Our Hands". The plot concerns the discovery and subsequent sale at auction of Harrison's Lesser Watch H6. The watch was auctioned off at Sotheby's for £6.2 million. This was the episode in which Derek 'Del Boy' Trotter and Rodney Trotter finally become millionaires.

In 1998, British Composer Harrison Birtwistle wrote the piano piece "Harrison's clocks" that contains musical depictions of Harrison's various clocks. Composer Peter Graham's piece Harrison's Dream is about Harrison's forty-year quest to produce an accurate clock. Graham worked simultaneously on the brass band and wind band versions of the piece, which received their first performances just four months apart, in October 2000 and February 2001 respectively.

The song "John Harrison's Hands", written by Brian McNeill and Dick Gaughan, appeared on the 2001 album Outlaws & Dreamers. The song has also been covered by Steve Knightley, appearing on his album 2011 Live In Somerset. It was further covered by the British band Show of Hands and appears on their 2016 album The Long Way Home.

In the final years of his life, John Harrison wrote about his research into musical tuning and Manufacturing methods for bells. His tuning system, (a meantone system derived from pi), is described in his pamphlet A Description Concerning Such Mechanism ... (CSM). This system challenged the traditional view that harmonics occur at integer frequency ratios and in consequence all music using this tuning produces low frequency beating. In 2002, Harrison's last manuscript, A true and short, but full Account of the Foundation of Musick, or, as principally therein, of the Existence of the Natural Notes of Melody, was rediscovered in the US Library of Congress. His theories on the mathematics of bell Manufacturing (using "Radical Numbers") are yet to be clearly understood.

Harrison's last home was 12, Red Lion Square, in the Holborn district of London. There is a plaque dedicated to Harrison on the wall of Summit House, a 1925 modernist office block, on the south side of the square. A memorial tablet to Harrison was unveiled in Westminster Abbey on 24 March 2006, finally recognising him as a worthy companion to his friend George Graham and Thomas Tompion, 'The Father of English Watchmaking', who are both buried in the Abbey. The memorial shows a meridian line (line of constant longitude) in two metals to highlight Harrison's most widespread invention, the bimetallic strip thermometer. The strip is engraved with its own longitude of 0 degrees, 7 minutes and 35 seconds West.

The Corpus Clock in Cambridge, unveiled in 2008, is a homage by the designer to Harrison's work but is of an electromechanical design. In appearance it features Harrison's grasshopper escapement, the 'pallet frame' being sculpted to resemble an actual grasshopper. This is the clock's defining feature.

Initially, the cost of these chronometers was quite high (roughly 30% of a ship's cost). However, over time, the costs dropped to between £25 and £100 (half a year's to two years' salary for a skilled worker) in the early 19th century. Many historians point to relatively low production volumes over time as evidence that the chronometers were not widely used. However, Landes points out that the chronometers lasted for decades and did not need to be replaced frequently – indeed the number of makers of marine chronometers reduced over time due to the ease in supplying the demand even as the merchant marine expanded. Also, many merchant mariners would make do with a deck chronometer at half the price. These were not as accurate as the boxed marine chronometer but were adequate for many. While the Lunar Distances method would complement and rival the marine chronometer initially, the chronometer would overtake it in the 19th century.

In 2014, Northern Rail renamed its train that runs between Barton and Cleethorpes as the John 'Longitude' Harrison.

One of the controversial claims of his last years was that of being able to build a land clock more accurate than any competing design. Specifically, he claimed to have designed a clock capable of keeping accurate to within one second over a span of 100 days. At the time, such publications as The London Review of English and Foreign Literature ridiculed Harrison for what was considered an outlandish claim. Harrison drew a design but never built such a clock himself, but in 1970 Martin Burgess, a Harrison expert and himself a clockmaker, studied the plans and endeavored to build the timepiece as drawn. He built two versions, dubbed Clock A and Clock B. Clock A became the Gurney Clock which was given to the city of Norwich in 1975, while Clock B lay unfinished in his workshop for decades until it was acquired in 2009 by Donald Saff. The completed Clock B was submitted to the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich for further study. It was found that Clock B could potentially meet Harrison's original claim, so the clock's design was carefully checked and adjusted. Finally, over a 100-day period from 6 January to 17 April 2015, Clock B was secured in a transparent case in the Royal Observatory and left to run untouched, apart from regular winding. Upon completion of the run, the clock was measured to have lost only 5/8 of a second, meaning Harrison's design was fundamentally sound. If we ignore the fact that this clock uses materials such as invar and duraluminium unavailable to Harrison, had it been built in 1762, the date of Harrison's testing of his H4, and run continuously since then without correction, it would now (April 2018) be slow by just 9 minutes and 45 seconds. Guinness World Records has declared the Martin Burgess' Clock B the "most accurate mechanical clock with a pendulum swinging in free air."

On 3 April 2018, Google celebrated his 325th birthday by making a Google Doodle for its homepage.