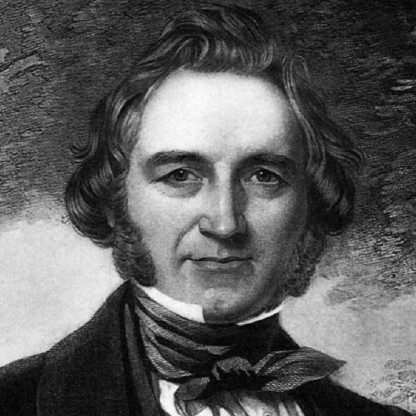

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Gardener & Architect |

| Birth Day | August 18, 2003 |

| Birth Place | Bedfordshire, British |

| Age | 17 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | June 8, 1865 |

| Birth Sign | Virgo |

Net worth

Joseph Paxton was a highly regarded figure in British history, renowned for his exceptional skills as both a gardener and an architect. In 2024, his net worth is estimated to range from $100K to $1M, a testament to his success and influence in his field. Throughout his career, Paxton showcased his talent through various innovative designs, most notably the Crystal Palace, a triumph in Victorian architecture. With his impressive contributions to British horticulture and design, Joseph Paxton remains an icon in the realm of gardening and architecture even to this day.

Biography/Timeline

Paxton was born in 1803, the seventh son of a farming family, in Milton Bryan, Bedfordshire. Some references, incorrectly, list his birth year as 1801. This is, as he admitted in later life, a result of misinformation he provided in his teens, which enabled him to enrol at Chiswick Gardens. He became a garden boy at the age of fifteen for Sir Gregory Osborne Page-Turner at Battlesden Park, near Woburn. After several moves, he obtained a position in 1823 at the Horticultural Society's Chiswick Gardens.

Although the duke was in Russia, Paxton set off for Chatsworth on the Chesterfield coach arriving at Chatsworth at half past four in the morning. By his own account he had explored the gardens after scaling the kitchen garden wall, set the staff to work, eaten breakfast with the housekeeper and met his Future wife, Sarah Bown, the housekeeper's niece, completing his first morning's work before nine o'clock. He married Bown in 1827, and she proved capable of managing his affairs, leaving him free to pursue his ideas.

In 1831, Paxton published a monthly magazine, The Horticultural Register. This was followed by the Magazine of Botany in 1834, the Pocket Botanical Dictionary in 1840, The Flower Garden in 1850 and the Calendar of Gardening Operations. In addition to these titles he also, in 1841, co-founded perhaps the most famous horticultural periodical, The Gardeners' Chronicle along with John Lindley, Charles Wentworth Dilke and william Bradbury and later became its Editor.

In 1832, Paxton developed an interest in greenhouses at Chatsworth where he designed a series of buildings with "forcing frames" for espalier trees and for the cultivation of exotic plants such as highly prized pineapples. At the time the use of glass houses was in its infancy and those at Chatsworth were dilapidated. After experimentation, he designed a glass house with a ridge and furrow roof that would be at right angles to the morning and evening sun and an ingenious frame design that would admit maximum light: the forerunner of the modern greenhouse.

Between 1835 and 1839, he organised plant-hunting expeditions one of which ended in tragedy when two gardeners from Chatsworth sent to California drowned. Tragedy also struck at home when his eldest son died.

In 1836, Paxton began the Great Conservatory, or Stove, a huge glasshouse, 227 ft (69 m) long and 123 ft (37 m) wide. The columns and beams were made of cast iron, and the arched elements of laminated wood. At the time, the conservatory was the largest glass building in the world. The largest sheet glass available at that time, made by Robert Chance, was 3 ft (0.91 m) long. Chance produced 4 ft (1.2 m) sheets for Paxton's benefit. The structure was heated by eight boilers using seven miles (11 km) of iron pipe and cost more than £30,000. It had a central carriageway and when the Queen was driven through, it was lit with twelve thousand lamps. It was prohibitively expensive to maintain, and was not heated during the First World War. The plants died and it was demolished in the 1920s.

While at Chatsworth, he built the Emperor Fountain in 1844, it was twice the height of Nelson's Column and required the creation of a feeder lake on the hill above the gardens necessitating the excavation of 100,000 cu yd (76,000 m) of earth.

In 1848 Paxton created the Conservative Wall, a glass house 331 ft (101 m) long by 7 ft (2.1 m) wide.

In 1850 Paxton was commissioned by Baron Mayer de Rothschild to design Mentmore Towers in Buckinghamshire. This was to be one of the greatest country houses built during the Victorian Era. Following the completion of Mentmore, Baron James de Rothschild, one of Baron de Rothschild's French cousins, commissioned Château de Ferrières at Ferrières-en-Brie near Paris to be "Another Mentmore, but twice the size". Both buildings still stand today.

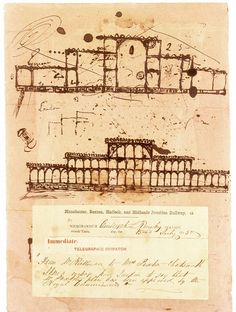

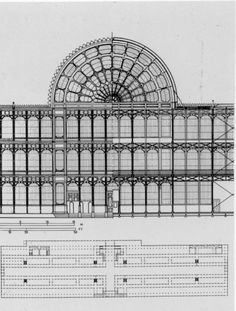

The Great Conservatory was the test-bed for the prefabricated glass and iron structural techniques which Paxton pioneered and would employ for his masterpiece: The Crystal Palace of the Great Exhibition of 1851. These techniques were made physically possible by recent technological advances in the manufacture of both glass and cast iron, and financially possible by the dropping of a tax on glass.

Paxton was a Liberal Member of Parliament for Coventry from 1854 until his death in 1865.

In June 1855 he presented a scheme he called the Great Victorian Way to the Parliamentary Select Committee on Metropolitan Communications in which he envisioned the construction of an arcade, based on the structure of the Crystal Palace, in a ten-mile loop around the centre of London. It would have incorporated a roadway, an atmospheric railway, housing and shops.

He became affluent, not so much through his Chatsworth employment, but by successful speculation in the railway industry. He retired from Chatsworth when the Duke died in 1858 but carried on working at various projects such as the Thames Graving Dock. Paxton died at his home at Rockhills, Sydenham, in 1865 and was buried on the Chatsworth Estate in St Peter's Churchyard, Edensor. His wife Sarah remained at their house on the Chatsworth Estate until her death in 1871.

On 17 March 1860, during the enthusiasm for the Volunteer movement, Paxton raised and commanded the 11th (Matlock) Derbyshire Rifle Volunteer Corps.

Its novelty was its revolutionary modular, prefabricated design, and use of glass. Glazing was carried out from special trolleys, and was fast: one man managed to fix 108 panes in a single day. The Palace was 1,848 ft (563 m) long, 408 ft (124 m) wide and 108 ft (33 m) high. It required 4,500 tons of iron, 60,000 sq ft (5,600 m) of timber and needed over 293,000 panes of glass. Yet it took 2,000 men just eight months to build, and cost just £79,800. Quite unlike any other building, it was itself a demonstration of British Technology in iron and glass. In its construction, Paxton was assisted by Charles Fox, also of Derby for the iron framework, and william Cubitt, Chairman of the Building Committee. All three were knighted. After the exhibition they were employed by the Crystal Palace Company to move it to Sydenham where it was destroyed in 1936 by a fire.