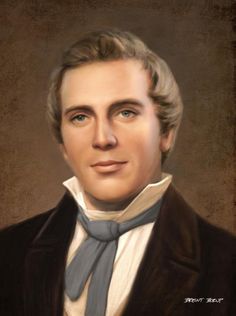

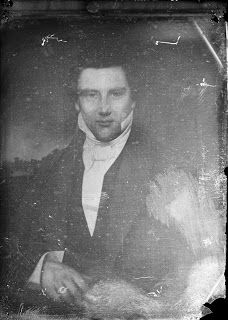

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | 1st President of the Church of Christ (later the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints) |

| Birth Day | December 23, 1805 |

| Birth Place | Sharon, Vermont, United States, United States |

| Age | 214 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | June 27, 1844(1844-06-27) (aged 38)\nCarthage, Illinois, United States |

| Birth Sign | Capricorn |

| Successor | Chancy Robison |

| End reason | Death |

| Predecessor | John C. Bennett |

| Political party | Independent |

| Resting place | Smith Family Cemetery 40°32′26″N 91°23′33″W / 40.54052°N 91.39244°W / 40.54052; -91.39244 (Smith Family Cemetery) |

| Spouse(s) | Emma Smith and multiple others (while the exact number of wives is uncertain, Joseph had multiple wives during his adult life) |

| Children | Julia Murdock Smith, Joseph Smith III, Alexander Hale Smith, David Hyrum Smith, others. |

| Parents | Joseph Smith Sr. Lucy Mack Smith |

| Website | Official website |

Net worth

Joseph Smith Jr.'s net worth is estimated to be between $100,000 to $1 million in 2024. Joseph Smith Jr. is best known as the 1st President of the Church of Christ, which later became known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, in the United States. As the founder of the Mormon religion, Smith played a significant role in the establishment and growth of the church. Despite facing various challenges and controversies during his lifetime, his religious leadership and teachings had a profound impact, leading to the establishment of a large and thriving religious community.

Biography/Timeline

Joseph Smith Jr. was born on December 23, 1805, in Sharon, Vermont, to Lucy Mack Smith and her husband Joseph Sr., a merchant and farmer. After suffering a crippling bone infection when he was seven, the younger Smith used crutches for three years. In 1816–17, after an ill-fated Business venture and three years of crop failures, the Smith family moved to the western New York village of Palmyra, and eventually took a mortgage on a 100-acre (40 ha) farm in the nearby town of Manchester.

During the Second Great Awakening, the region was a hotbed of religious enthusiasm. Between 1817 and 1825, there were several camp meetings and revivals in the Palmyra area. Although Smith's parents disagreed about religion, the family was caught up in this excitement. Smith later said he became interested in religion by about the age of twelve. As a teenager, he may have been sympathetic to Methodism. With other family members, Smith also engaged in religious folk magic, which was a relatively Common practice in that time and place. Both his parents and his maternal grandfather reportedly had visions or dreams that they believed communicated messages from God. Smith said that, although he had become concerned about the welfare of his soul, he was confused by the claims of competing religious denominations.

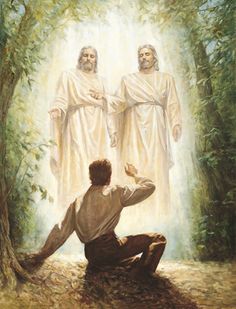

Years later, Smith claimed to have received a vision that resolved his religious confusion. In 1820, while praying in a wooded area near his home, he said that God, in a vision, had told him his sins were forgiven and that all contemporary churches had "turned aside from the gospel." Smith said he told the experience to a preacher, who dismissed the story with contempt. The event would later grow in importance to Smith's followers, who now regard it as the first event in the gradual restoration of Christ's church to earth. Until the 1840s, however, the experience was largely unknown, even to most Mormons. Smith may have originally understood the event simply as a personal conversion.

Smith never said how he produced the Book of Mormon, saying only that he translated by the power of God and implying that he had transcribed the words. The Book of Mormon itself states only that its text will "come forth by the gift and power of God unto the interpretation thereof". As such, considerable disagreement about the actual method used exists. For at least some of the earliest dictation, Smith is said to have used the "Urim and Thummim", a pair of seer stones he said were buried with the plates. Later, however, he is said to have used a chocolate-colored stone he had found in 1822 that he had used previously for treasure hunting. Joseph Knight said that Smith saw the words of the translation while he gazed at the stone or stones in the bottom of his hat, excluding all light, a process similar to divining the location of treasure. Sometimes, Smith concealed the process by raising a curtain or dictating from another room, while at other times he dictated in full view of witnesses while the plates lay covered on the table. After completing the translation, Smith gave the brown stone to Cowdery, but continued to receive revelations using another stone until about 1833 when he said he no longer needed it.

According to his later accounts, Smith was visited by an angel named Moroni, while praying one night in 1823. Smith said that this angel revealed the location of a buried book made of golden plates, as well as other artifacts, including a breastplate and a set of interpreters composed of two seer stones set in a frame, which had been hidden in a hill near his home. Smith said he attempted to remove the plates the next morning, but was unsuccessful because the angel returned and prevented him. Smith reported that during the next four years, he made annual visits to the hill, but each time returned without the plates.

Meanwhile, the Smith family faced financial hardship, due in part to the death of Smith's oldest brother Alvin, who had assumed a leadership role in the family. Family members supplemented their meager farm income by hiring out for odd jobs and working as treasure seekers, a type of magical supernaturalism Common during the period. Smith was said to have an ability to locate lost items by looking into a seer stone, which he also used in treasure hunting, including several unsuccessful attempts to find buried treasure sponsored by a wealthy farmer in Chenango County, New York. In 1826, Smith was brought before a Chenango County court for "glass-looking", or pretending to find lost treasure. The result of the proceeding remains unclear as primary sources report various conflicting outcomes.

In October 1827, Smith and his wife moved from Palmyra to Harmony (now Oakland), Pennsylvania, aided by a relatively prosperous neighbor, Martin Harris. Living near his in-laws, Smith transcribed some characters that he said were engraved on the plates, and then dictated a translation to his wife.

The first of Smith's wives, Emma Hale, gave birth to nine children during their marriage, five of whom died before the age of two. The eldest, Alvin (born in 1828), died within hours of birth, as did twins Thaddeus and Louisa (born in 1831). When the twins died, the Smiths adopted another set of twins, Julia and Joseph, whose mother had recently died in childbirth; Joseph died of measles in 1832. In 1841, Don Carlos, who had been born a year earlier, died of malaria. In 1842, Emma gave birth to a stillborn son. Joseph and Emma had four sons who lived to maturity: Joseph Smith III, Frederick Granger Williams Smith, Alexander Hale Smith, and David Hyrum Smith. Some historians have speculated—based on journal entries and family stories—that Smith may have fathered children with his plural wives. However, all DNA testing of potential Smith descendants from wives other than Emma has been negative.

Smith said that the angel returned the plates to him in September, 1828. In April 1829, he met Oliver Cowdery, who replaced Harris as his scribe, and resumed dictation. They worked full time on the manuscript between April and early June 1829, and then moved to Fayette, New York, where they continued to work at the home of Cowdery's friend, Peter Whitmer. When the narrative described an institutional church and a requirement for baptism, Smith and Cowdery baptized each other. Dictation was completed around July 1, 1829.

On the issue of slavery, Smith took different positions. Initially he opposed it, but during the mid-1830s when the Mormons were settling in Missouri (a slave state), Smith cautiously justified slavery in a strongly anti-abolitionist essay. Then in the early 1840s, after Mormons had been expelled from Missouri, he once again opposed slavery. During his presidential campaign of 1844, he proposed ending slavery by 1850 and compensating slaveholders for their loss. Smith said that blacks were not inherently inferior to whites, and he welcomed slaves into the church. However, he opposed baptizing them without permission of their masters, and he opposed interracial marriage.

By some accounts, Smith had been teaching a polygamy doctrine as early as 1831, and there is unconfirmed evidence that Smith was a polygamist by 1835. Although the church had publicly repudiated polygamy, in 1837 there was a rift between Smith and Oliver Cowdery over the issue. Cowdery suspected Smith had engaged in a relationship with his serving girl, Fanny Alger. Smith never denied a relationship, but insisted it was not adulterous, presumably because he had taken Alger as a plural wife.

Before 1832, most of Smith's revelations dealt with establishing the church, gathering his followers, and building the City of Zion. Later revelations dealt primarily with the priesthood, endowment, and exaltation. The pace of formal revelations slowed during the autumn of 1833, and again after the dedication of the Kirtland Temple. Smith moved away from formal written revelations spoken in God's voice, and instead taught more in sermons, conversations, and letters. For instance, the doctrines of baptism for the dead and the nature of God were introduced in sermons, and one of Smith's most famed statements about there being "no such thing as immaterial matter" was recorded from a Casual conversation with a Methodist preacher.

Also in 1833, at a time of temperance agitation, Smith delivered a revelation called the "Word of Wisdom," which counseled a diet of wholesome herbs, fruits, grains, a sparing use of meat. It also recommended that Latter Day Saints avoid "strong" alcoholic drinks, tobacco, and "hot drinks" (later interpreted to mean tea and coffee). The Word of Wisdom was not originally framed as a commandment, but a recommendation. As such, Smith and other Latter Day Saints did not strictly follow this counsel, though it later became a requirement in the LDS Church. In 1835, Smith gave the "great revelation" that organized the priesthood into quorums and councils, and functioned as a complex blueprint for church structure. Smith's last revelation, on the "New and Everlasting Covenant", was recorded in 1843, and dealt with the theology of family, the doctrine of sealing, and plural marriage.

In 1835, Smith encouraged some Latter Day Saints in Kirtland to purchase rolls of ancient Egyptian papyri from a traveling exhibitor. Over the next several years, Smith worked to produce what he reported was a translation of one of these rolls, which was published in 1842 as the Book of Abraham. The Book of Abraham speaks of the founding of the Abrahamic nation, astronomy, cosmology, lineage and priesthood, and gives another account of the creation story. The papyri from which Smith dictated the Book of Abraham were thought to have been lost in the Great Chicago Fire. However, several fragments were rediscovered in the 1960s, were translated by Egyptologists, and were determined to be part of the Book of the Dead with no connection to Abraham. The LDS Church has proposed that Smith might have been inspired by the papyri rather than have been translating them literally, but prominent Egyptologists note that Smith copied characters from the scrolls and was specific about their meaning.

After the Camp returned, Smith drew heavily from its participants to establish five governing bodies in the church, all originally of equal authority to check one another. Among these five groups was a quorum of twelve apostles. Smith gave a revelation saying that to redeem Zion, his followers would have to receive an endowment in the Kirtland Temple, and in March 1836, at the temple's dedication, many participants in the promised endowment saw visions of angels, spoke in tongues, and prophesied.

In January 1837, Smith and other church Leaders created a joint stock company, called the Kirtland Safety Society Anti-Banking Company, to act as a quasi-bank; the company issued bank notes capitalized in part by real estate. Smith encouraged the Latter Day Saints to buy the notes, and he invested heavily in them himself, but the bank failed within a month. As a result, the Latter Day Saints in Kirtland suffered intense pressure from debt Collectors and severe price volatility. Smith was held responsible for the failure, and there were widespread defections from the church, including many of Smith's closest advisers. After a warrant was issued for Smith's arrest on a charge of banking fraud, Smith and Rigdon fled Kirtland for Missouri in January 1838.

On August 6, 1838, non-Mormons in Gallatin tried to prevent Mormons from voting, and the election-day scuffles initiated the 1838 Mormon War. Non-Mormon vigilantes raided and burned Mormon farms, while Danites and other Mormons pillaged non-Mormon towns. In the Battle of Crooked River, a group of Mormons attacked the Missouri state militia, mistakenly believing them to be anti-Mormon vigilantes. Governor Lilburn Boggs then ordered that the Mormons be "exterminated or driven from the state". On October 30, a party of Missourians surprised and killed seventeen Mormons in the Haun's Mill massacre.

Many American newspapers criticized Missouri for the Haun's Mill massacre and the state's expulsion of the Latter Day Saints. Illinois accepted Mormon refugees who gathered along the banks of the Mississippi River, where Smith purchased high-priced, swampy woodland in the hamlet of Commerce. Smith also attempted to portray the Latter Day Saints as an oppressed minority, and unsuccessfully petitioned the federal government for help in obtaining reparations. During the summer of 1839, while Latter Day Saints in Nauvoo suffered from a malaria epidemic, Smith sent Brigham Young and other apostles to missions in Europe, where they made numerous converts, many of them poor factory workers.

During the early 1840s, Smith unfolded a theology of family relations called the "New and Everlasting Covenant" that superseded all earthly bonds. He taught that outside the Covenant, marriages were simply matters of contract, and that in the afterlife individuals married outside the Covenant or not married would be limited in their progression. To fully enter the Covenant, a man and woman must participate in a "first anointing", a "sealing" ceremony, and a "second anointing" (also called "sealing by the Holy Spirit of Promise"). When fully sealed into the Covenant, Smith said that no sin nor blasphemy (other than the eternal sin) could keep them from their exaltation in the afterlife. According to Smith, only one person on earth at a time—in this case, Smith—could possess this power of sealing.

In April 1841, Smith wed Louisa Beaman. During the next two-and-a-half years he married or was sealed to about 30 additional women, ten of whom were already married to other men. Some of these polyandrous marriages were done with the consent of the first husbands, and some plural marriages may have been considered "eternity-only" sealings (meaning that the marriage would not take effect until after death). Ten of Smith's plural wives were between the ages of fourteen and twenty; others were over fifty. The practice of polygamy was kept secret from both non-Mormons and most members of the church during Smith's lifetime.

By mid-1842, popular opinion had turned against the Mormons. After an unknown assailant shot and wounded Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs in May 1842, anti-Mormons circulated rumors that Smith's bodyguard, Porter Rockwell, was the shooter. Though the evidence was circumstantial, Boggs ordered Smith's extradition. Certain he would be killed if he ever returned to Missouri, Smith went into hiding twice during the next five months, before the U.S. district attorney for Illinois argued that Smith's extradition to Missouri would be unconstitutional. (Rockwell was later tried and acquitted.) In June 1843, enemies of Smith convinced a reluctant Illinois Governor Thomas Ford to extradite Smith to Missouri on an old charge of treason. Two law officers arrested Smith, but were intercepted by a party of Mormons before they could reach Missouri. Smith was then released on a writ of habeas corpus from the Nauvoo municipal court. While this ended the Missourians' attempts at extradition, it caused significant political fallout in Illinois.

Polygamy caused a breach between Smith and his first wife, Emma. Although Emma knew of some of her husband's marriages, she almost certainly did not know the extent of his polygamous activities. In 1843, Emma temporarily accepted Smith's marriage to four women boarded in the Smith household, but soon regretted her decision and demanded the other wives leave. In July 1843, Smith dictated a revelation directing Emma to accept plural marriage, but the two were not reconciled until September 1843, after Emma began participating in temple ceremonies.

While campaigning for President of the United States in 1844, Smith had opportunity to take political positions on issues of the day. Smith considered the U.S. Constitution, and especially the Bill of Rights, to be inspired by God and "the [Latter Day] Saints' best and perhaps only defense.". He believed a strong central government was crucial to the nation's well-being and thought democracy better than tyranny—although he also taught that a theocratic monarchy was the ideal form of government. In foreign affairs, Smith was an expansionist, though he viewed "expansionism as brotherhood".

Throughout her life, Emma Smith frequently denied that her husband had ever taken additional wives. Emma said that the very first time she ever became aware of a polygamy revelation being attributed to Smith by Mormons was when she read about it in Orson Pratt's periodical The Seer in 1853. Emma campaigned publicly against polygamy, and was the main signatory of a petition in 1842, with a thousand female signatures, denying that Smith was connected with polygamy. As President of the Ladies' Relief Society, Emma authorized publishing a certificate in the same year denouncing polygamy, and denying her husband as its creator or participant. Even on her deathbed, Emma denied Joseph's involvement with polygamy, stating, "No such thing as polygamy, or spiritual wifery, was taught, publicly or privately, before my husband's death, that I have now, or ever had any knowledge of ... He had no other wife but me; nor did he to my knowledge ever have".

After Smith's death, Emma Smith quickly became alienated from Brigham Young and the church leadership. Young, whom Emma feared and despised, was suspicious of her Desire to preserve the family's assets from inclusion with those of the church, and thought she would be even more troublesome because she openly opposed plural marriage. When most Latter Day Saints moved west, she stayed in Nauvoo, married a non-Mormon, Major Lewis C. Bidamon, and withdrew from religion until 1860, when she affiliated with the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, first headed by her son, Joseph Smith III. Emma never denied Smith's prophetic gift or repudiated her belief in the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.

The two strongest succession candidates were Brigham Young, senior member and President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and Sidney Rigdon, the senior member of the First Presidency. In a church-wide conference on August 8, most of the Latter Day Saints elected Young, who led them to the Utah Territory as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). Membership in Young's denomination surpassed 14 million members in 2010. Smaller groups followed Sidney Rigdon and James J. Strang, who had based his claim on an allegedly-forged letter of appointment. Others followed Lyman Wight and Alpheus Cutler. Many members of these smaller groups, including most of Smith's family, eventually coalesced in 1860 under the leadership of Joseph Smith III and formed what was known for more than a century as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now Community of Christ), which now has about 250,000 members. As of 2013, members of the denominations originating from Smith's teachings number approximately 15 million.

Smith also attracted a few wealthy and influential converts, including John C. Bennett, the Illinois quartermaster general. Bennett used his connections in the Illinois legislature to obtain an unusually liberal charter for the new city, which Smith named "Nauvoo" (Hebrew נָאווּ, meaning "to be beautiful"). The charter granted the city virtual autonomy, authorized a university, and granted Nauvoo habeas corpus power—which allowed Smith to fend off extradition to Missouri. Though Mormon authorities controlled Nauvoo's civil government, the city promised an unusually liberal guarantee of religious freedom. The charter also authorized the Nauvoo Legion, an autonomous militia whose actions were limited only by state and federal constitutions. "Lieutenant General" Smith and "Major General" Bennett became its commanders, thereby controlling by far the largest body of armed men in Illinois. Smith made Bennett Assistant President of the church, and Bennett was elected Nauvoo's first mayor.