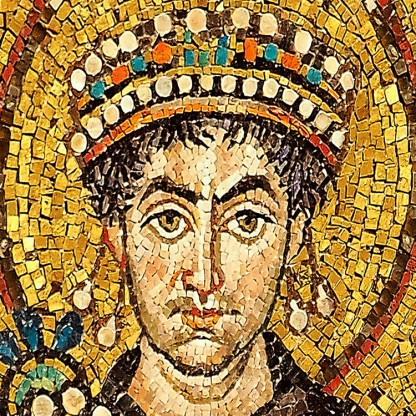

Age, Biography and Wiki

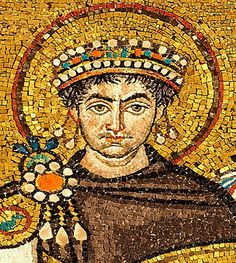

| Who is it? | Byzantine Emperor |

| Birth Place | Tauresium, Dardania, then part of Diocese of Dacia (in today's Republic of Macedonia, Macedonian |

| Died On | 14 November 565 (aged 83)\nConstantinople |

| Reign | 1 August 527 – 14 November 565 |

| Coronation | 1 August 527 |

| Predecessor | Justin I |

| Successor | Justin II |

| Burial | Church of the Holy Apostles, Constantinople modern day Istanbul, Turkey |

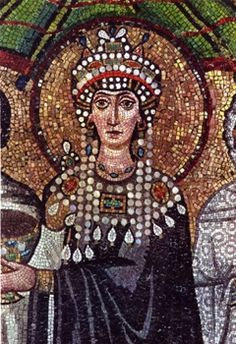

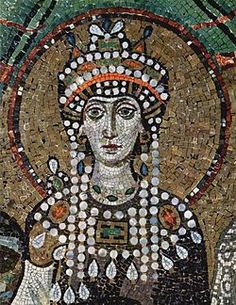

| Spouse | Theodora |

| Issue | unknown daughter John (adopted) Theodora (adopted) |

| Full nameRegnal name | Full name Petrus Sabbatius Regnal name Imperator Caesar Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Iustinianus Augustus Petrus SabbatiusImperator Caesar Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Iustinianus Augustus |

| Dynasty | Justinian |

| Father | Sabbatius Justin I (adoptive) |

| Mother | Vigilantia |

| Religion | Chalcedonian Christianity |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Lutheran Church Eastern Catholicism |

| Major shrine | Church of the Holy Apostles, Constantinople modern day Istanbul, Turkey |

| Feast | 14 November |

| Attributes | Imperial Vestment |

Net worth

Justinian I, also known as the Byzantine Emperor in Macedonian, is projected to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million by 2024. This esteemed ruler, who reigned from 527 to 565 AD, left a lasting legacy in the Byzantine Empire. Renowned for his Justinian Code and significant architectural projects like the Hagia Sophia, his reign reshaped the empire and solidified his place in history. While it is challenging to calculate the exact worth of a historical figure, estimates suggest that Justinian I amassed considerable wealth throughout his rule, making him a significant figure in Byzantine history.

Biography/Timeline

Justinian appears as a character in the 1939 time travel novel Lest Darkness Fall, by L. Sprague de Camp. The Glittering Horn: Secret Memoirs of the Court of Justinian was a novel written by Pierson Dixon in 1958 about the court of Justinian.

From the middle of the 5th century onward, increasingly arduous tasks confronted the emperors of the East in ecclesiastical matters. Justinian entered the arena of ecclesiastical statecraft shortly after his uncle's accession in 518, and put an end to the Acacian schism. Previous Emperors had tried to alleviate theological conflicts by declarations that deemphasized the Council of Chalcedon, which had condemned Monophysitism, which had strongholds in Egypt and Syria, and by tolerating the appointment of Monophysites to church offices. The Popes reacted by severing ties with the Patriarch of Constantinople who supported these policies. Emperors Justin I (and later Justinian himself) rescinded these policies and reestablished the union between Constantinople and Rome. After this, Justinian also felt entitled to settle disputes in papal elections, as he did when he favoured Vigilius and had his rival Silverius deported.

Early in his reign, Justinian appointed the quaestor Tribonian to oversee this task. The first draft of the Codex Iustinianus, a codification of imperial constitutions from the 2nd century onward, was issued on 7 April 529. (The final version appeared in 534.) It was followed by the Digesta (or Pandectae), a compilation of older legal texts, in 533, and by the Institutiones, a textbook explaining the principles of law. The Novellae, a collection of new laws issued during Justinian's reign, supplements the Corpus. As opposed to the rest of the corpus, the Novellae appeared in Greek, the Common language of the Eastern Empire.

Justinian's ambition to restore the Roman Empire to its former glory was only partly realized. In the West, the brilliant early military successes of the 530s were followed by years of stagnation. The dragging war with the Goths was a disaster for Italy, even though its long-lasting effects may have been less severe than is sometimes thought. The heavy taxes that the administration imposed upon its population were deeply resented. The final victory in Italy and the conquest of Africa and the coast of southern Hispania significantly enlarged the area over which the Empire could project its power and eliminated all naval threats to the empire. Despite losing much of Italy soon after Justinian's death, the empire retained several important cities, including Rome, Naples, and Ravenna, leaving the Lombards as a regional threat. The newly founded province of Spania kept the Visigoths as a threat to Hispania alone and not to the western Mediterranean and Africa. Events of the later years of the reign showed that Constantinople itself was not safe from barbarian incursions from the north, and even the relatively benevolent Historian Menander Protector felt the need to attribute the Emperor's failure to protect the capital to the weakness of his body in his old age. In his efforts to renew the Roman Empire, Justinian dangerously stretched its resources while failing to take into account the changed realities of 6th-century Europe.

Seven years later, in 542, a devastating outbreak of Bubonic Plague, known as the Plague of Justinian and second only to that of the 14th century, laid siege to the world, killing tens of millions. As ruler of the Empire, Justinian, and members of his court, were physically unaffected by famine. However, the Imperial Court did prove susceptible to plague, with Justinian himself contracting, but surviving, the pestilence.

The Corpus forms the basis of Latin jurisprudence (including ecclesiastical Canon Law) and, for historians, provides a valuable insight into the concerns and activities of the later Roman Empire. As a collection it gathers together the many sources in which the leges (laws) and the other rules were expressed or published: proper laws, senatorial consults (senatusconsulta), imperial decrees, case law, and jurists' opinions and interpretations (responsa prudentum). Tribonian's code ensured the survival of Roman law. It formed the basis of later Byzantine law, as expressed in the Basilika of Basil I and Leo VI the Wise. The only western province where the Justinianic code was introduced was Italy (after the conquest by the so-called Pragmatic Sanction of 554), from where it was to pass to Western Europe in the 12th century and become the basis of much European law code. It eventually passed to Eastern Europe where it appeared in Slavic editions, and it also passed on to Russia. It remains influential to this day.

At the start of Justinian I's reign he had inherited a surplus 28,800,000 solidi (400,000 pounds of gold) in the imperial treasury from Anastasius I and Justin I. Under Justinian's rule, measures were taken to counter corruption in the provinces and to make tax collection more efficient. Greater administrative power was given to both the Leaders of the prefectures and of the provinces, while power was taken away from the vicariates of the dioceses, of which a number were abolished. The overall trend was towards a simplification of administrative infrastructure. According to Brown (1971), the increased professionalization of tax collection did much to destroy the traditional structures of provincial life, as it weakened the autonomy of the town councils in the Greek towns. It has been estimated that before Justinian I's reconquests the state had an annual revenue of 5,000,000 solidi in AD 530, but after his reconquests, the annual revenue was increased to 6,000,000 solidi in AD 550.

This new-found unity between East and West did not, however, solve the ongoing disputes in the east. Justinian's policies switched between attempts to force Monophysites to accept the Chalcedonian creed by persecuting their bishops and monks – thereby embittering their sympathizers in Egypt and other provinces – and attempts at a compromise that would win over the Monophysites without surrendering the Chalcedonian faith. Such an approach was supported by the Empress Theodora, who favoured the Monophysites unreservedly. In the condemnation of the Three Chapters, three Theologians that had opposed Monophysitism before and after the Council of Chalcedon, Justinian tried to win over the opposition. At the Fifth Ecumenical Council, most of the Eastern church yielded to the Emperor's demands, and Pope Vigilius, who was forcibly brought to Constantinople and besieged at a champel, finally also gave his assent. However, the condemnation was received unfavourably in the west, where it led to new (albeit temporal) schism, and failed to reach its goal in the east, as the Monophysites, remained unsatisfied; all the more bitter for him because during his last years he took an even greater interest in theological matters.

In the Paradiso section of the Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri, Justinian I is prominently featured as a spirit residing on the sphere of Mercury, which holds the ambitious souls of Heaven. His legacy is elaborated on, and he is portrayed as a defender of the Christian faith and the restorer of Rome to the Empire. However, Justinian confesses that he was partially motivated by fame rather than duty to God, which tainted the justice of his rule in spite of his proud accomplishments. In his introduction, "Cesare fui e son Iustinïano" ("Caesar I was, and am Justinian"), his mortal title is contrasted with his immortal soul, to emphasize that glory in life is ephemeral, while contributing to God's glory is eternal, according to Dorothy L. Sayers. Dante also uses Justinian to criticize the factious politics of his 14th Century Italy, in contrast to the unified Italy of the Roman Empire.