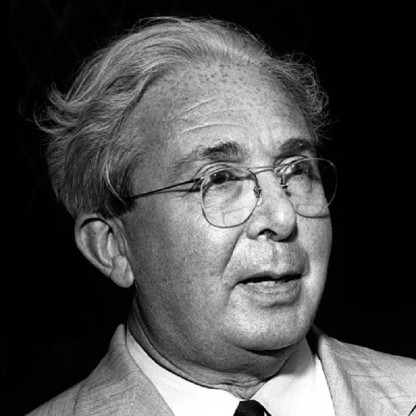

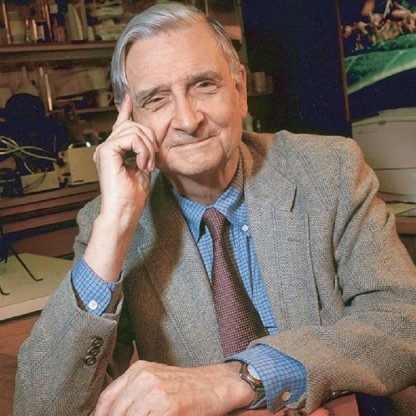

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Physicist |

| Birth Day | February 11, 1898 |

| Birth Place | Budapest, United States |

| Age | 121 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | May 30, 1964(1964-05-30) (aged 66)\nLa Jolla, California, United States |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Residence | Hungary, Germany, United Kingdom, United States |

| Citizenship | Hungary Germany United States |

| Alma mater | Budapest Technical University Technical University of Berlin Humboldt University |

| Known for | Nuclear chain reaction Szilárd petition Einstein–Szilárd letter Cobalt bomb Absorption refrigerator Szilárd Engine Szilard–Chalmers effect Einstein–Szilard refrigerator |

| Awards | Atoms for Peace Award (1959) Albert Einstein Award (1960) |

| Fields | Physics, biology |

| Institutions | Humboldt University of Berlin Columbia University University of Chicago Salk Institute |

| Thesis | Über die thermodynamischen Schwankungserscheinungen (1923) |

| Doctoral advisor | Max von Laue |

| Other academic advisors | Albert Einstein |

Net worth: $16 Million (2024)

Leó Szilárd, a renowned physicist known for his contributions in the United States, is projected to have a net worth of approximately $16 million by the year 2024. Szilárd's pioneering work in nuclear physics, particularly his role in the development of the atomic bomb, has earned him widespread recognition and accolades. Alongside his scientific achievements, Szilárd's entrepreneurial ventures and intellectual property rights have undoubtedly contributed to his substantial wealth. As one of the most esteemed physicists in the field, Szilárd's net worth is a testament to his remarkable accomplishments and the significant impact he has made on the scientific community.

Famous Quotes:

We might in these processes obtain very much more energy than the proton supplied, but on the average we could not expect to obtain energy in this way. It was a very poor and inefficient way of producing energy, and anyone who looked for a source of power in the transformation of the atoms was talking moonshine. But the subject was scientifically interesting because it gave insight into the atoms.

Biography/Timeline

Leo Spitz was born in Budapest in what was then the Kingdom of Hungary, on February 11, 1898. His middle-class Jewish parents, Louis Spitz, a civil Engineer, and Tekla Vidor, raised Leó on the Városligeti Fasor in Pest. He had two younger siblings, a brother, Béla, born in 1900, and a sister, Rózsi (Rose), born in 1901. On October 4, 1900, the family changed its surname from the German "Spitz" to the Hungarian "Szilard", a name that means "solid" in Hungarian. Despite having a religious background, Szilard became an agnostic. From 1908 to 1916 he attended Reáliskola high school in his home town. Showing an early interest in physics and a proficiency in mathematics, in 1916 he won the Eötvös Prize, a national prize for mathematics.

With World War I raging in Europe, Szilard received notice on January 22, 1916, that he had been drafted into the 5th Fortress Regiment, but he was able to continue his studies. He enrolled as an engineering student at the Palatine Joseph Technical University, which he entered in September 1916. The following year he joined the Austro-Hungarian Army's 4th Mountain Artillery Regiment, but immediately was sent to Budapest as an officer candidate. He rejoined his regiment in May 1918 but in September, before being sent to the front, he fell ill with Spanish Influenza and was returned home for hospitalization. Later he was informed that his regiment had been nearly annihilated in battle, so the illness probably saved his life. He was discharged honorably in November 1918, after the Armistice.

Convinced that there was no Future for him in Hungary, Szilard left for Berlin via Austria on December 25, 1919, and enrolled at the Technische Hochschule (Institute of Technology) in Berlin-Charlottenburg. He was soon joined by his brother Béla. Szilard became bored with engineering, and his attention turned to physics. This was not taught at the Technische Hochschule, so he transferred to Friedrich Wilhelm University, where he attended lectures given by Albert Einstein, Max Planck, Walter Nernst, James Franck and Max von Laue. He also met fellow Hungarian students Eugene Wigner, John von Neumann and Dennis Gabor. His doctoral dissertation on thermodynamics Über die thermodynamischen Schwankungserscheinungen (On The Manifestation of Thermodynamic Fluctuations), praised by Einstein, won top honors in 1922. It involved a long-standing puzzle in the philosophy of thermal and statistical physics known as Maxwell's demon, a thought experiment originated by the Physicist James Clerk Maxwell. The Problem was thought to be insoluble, but in tackling it Szilard recognized the connection between thermodynamics and Information theory.

Szilard was appointed as assistant to von Laue at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in 1924. In 1927 he finished his habilitation and became a Privatdozent (private lecturer) in physics. For his habilitation lecture, he produced a second paper on Maxwell's Demon, Über die Entropieverminderung in einem thermodynamischen System bei Eingriffen intelligenter Wesen (On the reduction of entropy in a thermodynamic system by the intervention of intelligent beings), that had actually been written soon after the first. This introduced the thought experiment now called the Szilard engine and became important in the history of attempts to understand Maxwell's demon. The paper is also the first equation of negative entropy and information. As such, it established Szilard as one of the founders of information theory, but he did not publish it until 1929, and did not pursue it further. Claude E. Shannon, who took it up in the 1950s, acknowledged Szilard's paper as his starting point.

Throughout his time in Berlin, Szilard worked on numerous technical inventions. In 1928 he submitted a patent application for the linear accelerator, not knowing of Gustav Ising's prior 1924 journal article and Rolf Widerøe's operational device, and in 1929 applied for one for the cyclotron. He also conceived the electron microscope. Between 1926 and 1930, he worked with Einstein to develop the Einstein refrigerator, notable because it had no moving parts. He did not build all of these devices, or publish these ideas in scientific journals, and so credit for them often went to others. As a result, Szilard never received the Nobel Prize, but Ernest Lawrence was awarded it for the cyclotron in 1939 and Ernst Ruska for the electron microscope in 1986.

On September 12, 1933, Szilard read an article in The Times summarizing a speech given by Lord Rutherford in which Rutherford rejected the feasibility of using atomic Energy for practical purposes. The speech remarked specifically on the recent 1932 work of his students, John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton, in "splitting" lithium into alpha particles, by bombardment with protons from a particle accelerator they had constructed. Rutherford went on to say:

In early 1934, Szilard began working at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London. Working with a young Physicist on the hospital staff, Thomas A. Chalmers, he began studying radioactive isotopes for medical purposes. It was known that bombarding elements with neutrons could produce either heavier isotopes of an element, or a heavier element, a phenomenon known as the Fermi Effect after its discoverer, the Italian Physicist Enrico Fermi. When they bombarded ethyl iodide with neutrons produced by a radon-beryllium source, they found that the heavier radioactive isotopes of iodine separated from the compound. Thus, they had discovered a means of isotope separation. This method became known as the Szilard–Chalmers effect, and was widely used in the preparation of medical isotopes. He also attempted unsuccessfully to create a nuclear chain reaction using beryllium by bombarding it with X-rays. In 1936, Szilard assigned his chain-reaction patent to the British Admiralty to ensure its secrecy.

In November 1938, Szilard moved to New York City, taking a room at the King's Crown Hotel near Columbia University. He encountered John R. Dunning, who invited him to speak about his research at an afternoon seminar in January 1939. That month, Niels Bohr brought news to New York of the discovery of nuclear fission in Germany by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann, and its theoretical explanation by Lise Meitner, and Otto Frisch. When Szilard found out about it on a visit to Wigner at Princeton University, he immediately realized that uranium might be the element capable of sustaining a chain reaction.

An Advisory Committee on Uranium was formed under Lyman J. Briggs, a scientist and the Director of the National Bureau of Standards. Its first meeting on October 21, 1939, was attended by Szilard, Teller, and Wigner, who persuaded the Army and Navy to provide $6,000 for Szilard to purchase supplies for experiments—in particular, more graphite. A 1940 Army intelligence report on Fermi and Szilard, prepared when the United States had not yet entered World War II, expressed reservations about both. While it contained some errors of fact about Szilard, it correctly noted his dire prediction that Germany would win the war.

The December 6, 1941, meeting of the National Defense Research Committee resolved to proceed with an all-out effort to produce atomic bombs, a decision given urgency by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the following day that brought the United States into World War II, and then formal approval by Roosevelt in January 1942. Arthur H. Compton from the University of Chicago was appointed head of research and development. Against Szilard's wishes, Compton concentrated all the groups working on reactors and plutonium at the Metallurgical Laboratory of the University of Chicago. Compton laid out an ambitious plan to achieve a chain reaction by January 1943, start Manufacturing plutonium in nuclear reactors by January 1944, and produce an atomic bomb by January 1945.

A vexing question at the time was how a production reactor should be cooled. Taking a conservative view that every possible neutron must be preserved, the majority opinion initially favored cooling with helium, which would absorb very few neutrons. Szilard argued that if this was a concern, then liquid bismuth would be a better choice. He supervised experiments with it, but the practical difficulties turned out to be too great. In the end, Wigner's plan to use ordinary water as a coolant won out. When the coolant issue became too heated, Compton and the Director of the Manhattan Project, Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, Jr., moved to dismiss Szilard, who was still a German citizen, but the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, refused to do so. Szilard was therefore present on December 2, 1942, when the first man-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was achieved in the first nuclear reactor under viewing stands of Stagg Field, and shook Fermi's hand.

Szilard became a naturalized citizen of the United States in March 1943. The Army offered Szilard $25,000 for his inventions before November 1940, when he officially joined the project. He refused. He was the co-holder, with Fermi, of the patent on the nuclear reactor. In the end he sold his patent to the government for reimbursement of his expenses, some $15,416, plus the standard $1 fee. He continued to work with Fermi and Wigner on nuclear reactor design, and is credited with coining the term "breeder reactor".

In 1946, Szilard secured a research professorship at the University of Chicago that allowed him to dabble in biology and the social sciences. He teamed up with Aaron Novick, a Chemist who had worked at the Metallurgical Laboratory during the war. The two men saw biology as a field that had not been explored as much as physics, and was ready for scientific breakthroughs. It was a field that Szilard had been working on in 1933 before he had become subsumed in the quest for a nuclear chain reaction. The duo made considerable advances. They invented the chemostat, a device for regulating the growth rate of the microorganisms in a bioreactor, and developed methods for measuring the growth rate of bacteria. They discovered feedback inhibition, an important factor in processes such as growth and metabolism. Szilard gave essential advice to Theodore Puck and Philip I. Marcus for their first cloning of a human cell in 1955.

In 1949 Szilard wrote a short story titled "My Trial as a War Criminal" in which he imagined himself on trial for crimes against humanity after the United States lost a war with the Soviet Union. He publicly sounded the alarm against the possible development of salted thermonuclear bombs, explaining in radio talk on February 26, 1950, that sufficiently big thermonuclear bomb rigged with specific but Common materials, might annihilate mankind. While Time magazine compared him to Chicken Little, and the Atomic Energy Commission dismissed the idea, Scientists debated whether it was feasible or not. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists commissioned a study by James R. Arnold that concluded that it was.

Before relation with his later wife Gertrud Weiss, Leo Szilard's life partner in the period 1927 – 1934 was kindergarten Teacher and opera singer Gerda Philipsborn, who also worked as a volunteer in a Berlin asylum organization for refugee children and in 1932 moved to India to continue in this work. Szilard married Gertrud (Trude) Weiss, a physician, in a civil ceremony in New York on October 13, 1951. They had known each other since 1929, and had frequently corresponded and visited each other ever since. Weiss took up a teaching position at the University of Colorado in April 1950, and Szilard began staying with her in Denver for weeks at a time when they had never been together for more than a few days before. Single people living together was frowned upon in the conservative United States at the time, and after they were discovered by one of her students, Szilard began to worry that she might lose her job. Their relationship remained a long-distance one, and they kept news of their marriage quiet. Many of his friends were shocked when they found out, as it was widely believed that Szilard was a born bachelor.

In 1960, Szilard was diagnosed with bladder cancer. He underwent cobalt therapy at New York's Memorial Sloan-Kettering Hospital using a cobalt 60 treatment regimen that he designed himself. A second round of treatment with an increased dose followed in 1962. The doctors tried to tell him that the increased radiation dose would kill him, but he said it wouldn't, and that anyway he would die without it. The higher dose did its job and his cancer never returned. This treatment became standard for many cancers and is still used.

Szilard published a book of short stories, The Voice of the Dolphins (1961), in which he dealt with the moral and ethical issues raised by the Cold War and his own role in the development of atomic weapons. The title story described an international biology research laboratory in Central Europe. This became reality after a meeting in 1962 with Victor F. Weisskopf, James Watson and John Kendrew. When the European Molecular Biology Laboratory was established, the library was named The Szilard Library and the library stamp features dolphins. Other honors that he received included the Atoms for Peace Award in 1959, and the Humanist of the Year in 1960. A lunar crater on the far side of the Moon was named after him in 1970. The Leo Szilard Lectureship Award, established in 1974, is given in his honor by the American Physical Society.

Szilard spent his last years as a fellow of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, which he had helped to create. He was appointed a non-resident fellow there in July 1963, and became a resident fellow on April 1, 1964, after moving to La Jolla in February. With Trude, he lived in a bungalow on the property of the Hotel del Charro. On May 30, 1964, he died there in his sleep of a heart attack; when Trude awoke, she was unable to revive him. His remains were cremated. His papers are in the library at the University of California in San Diego. In February 2014, the library announced that they received funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission to digitize its collection of his papers, extending from 1938 to 1998.