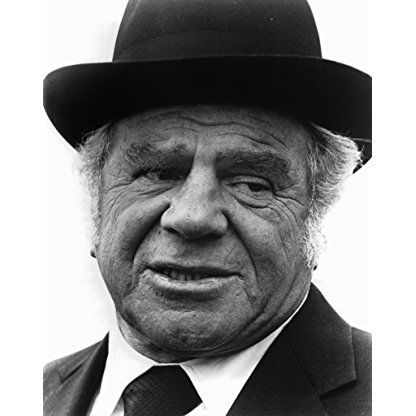

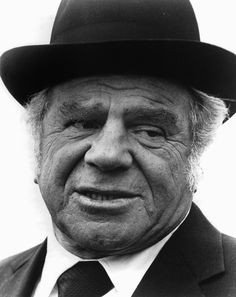

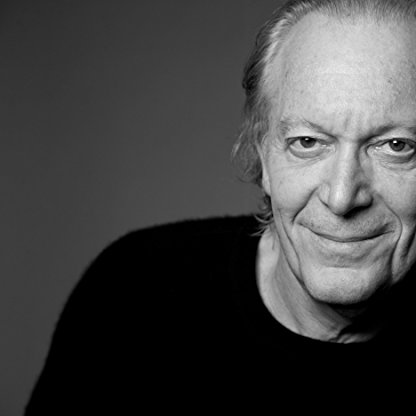

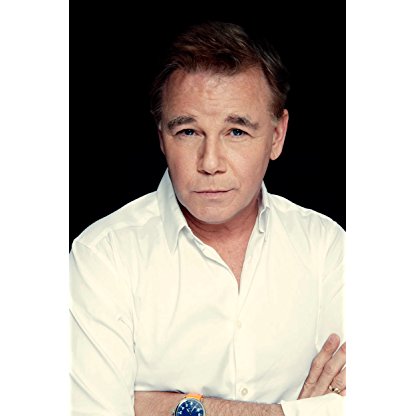

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Actor, Miscellaneous Crew |

| Birth Day | January 11, 1908 |

| Birth Place | The Bronx, New York City, New York, United States |

| Age | 112 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | November 30, 1994(1994-11-30) (aged 86)\nLos Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Aquarius |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1928–1994 |

| Spouse(s) | Lucy Dietz (1928-1936; divorced; 1 child: Mikele) Alice Twitchell (1938–1942; divorced) Vehanne Monteagle (1945 – 6 June 1950; divorced; 2 daughters) Diana Radbec (1953–1963; divorced; 1 daughter) Maria Penn (1963–1967; divorced; 1 daughter) Stephanie Van Hennick (1971–1994; his death; 1 child: Jennifer) |

Net worth: $13 Million (2024)

Lionel Stander was a highly respected actor and miscellaneous crew member in the United States. With an estimated net worth of $13 million in 2024, he had achieved great success throughout his career. Stander's talent and versatility allowed him to portray a wide range of characters, earning him critical acclaim and popularity among audiences. Known for his distinctive voice and memorable roles in both film and television, Stander's contributions to the entertainment industry left a lasting impact. His net worth is a testament to his dedication and talent within the realm of acting and production.

Famous Quotes:

"I am not a dupe, or a dope, or a moe, or a schmoe...I was absolutely conscious of what I was doing, and I am not ashamed of anything I said in public or private."

Biography/Timeline

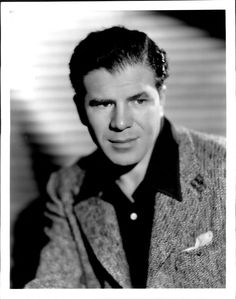

According to newspaper interviews with Stander, as a teenager he appeared in the silent film Men of Steel (1926), perhaps as an extra, since he is not listed in the credits.

Stander's acting career began in 1928, as Cop and First Fairy in Him by E. E. Cummings, at the Provincetown Playhouse. He claimed that he got the roles because one of them required shooting craps, which he did well, and a friend in the company volunteered him. He appeared in a series of short-lived plays through the early 1930s, including The House Beautiful, which Dorothy Parker famously derided as "the play lousy".

Stander's distinctive rumbling voice, tough-guy demeanor, and talent with accents made him a popular radio actor. In the 1930s and 1940s, he was on The Eddie Cantor Show, Bing Crosby's KMH show, the Lux Radio Theater production of A Star Is Born, The Fred Allen Show, the Mayor of the Town series with Lionel Barrymore and Agnes Moorehead, Kraft Music Hall on NBC, Stage Door Canteen on CBS, the Lincoln Highway Radio Show on NBC, and The Jack Paar Show, among others.

Stander's personal life was as tumultuous as his professional one. He was married six times, the first time in 1932 and the last in 1972. All but the last marriage ended in divorce. He fathered six daughters (one wife had no children, one had twins).

Strongly liberal and pro-labor, Stander espoused a variety of social and political causes, and was a founding member of the Screen Actors Guild. At a SAG meeting held during a 1937 studio technicians' strike, he told the assemblage of 2000 members: "With the eyes of the whole world on this meeting, will it not give the Guild a black eye if its members continue to cross picket lines?" (The NYT reported: "Cheers mingled with boos greeted the question.") Stander also supported the Conference of Studio Unions in its fight against the Mob-influenced International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE). Also in 1937, Ivan F. Cox, a deposed officer of the San Francisco longshoremen's union, sued Stander and a host of others, including union leader Harry Bridges, actors Fredric March, Franchot Tone, Mary Astor, James Cagney, Jean Muir, and Director william Dieterle. The charge, according to Time magazine, was "conspiring to propagate Communism on the Pacific Coast, causing Mr. Cox to lose his job".

In 1938, Columbia Pictures head Harry Cohn allegedly called Stander "a Red son of a bitch" and threatened a US$100,000 fine against any studio that renewed his contract. Despite critical acclaim for his performances, Stander's film work dropped off drastically. After appearing in 15 films in 1935 and 1936, he was in only six in 1937 and 1938. This was followed by just six films from 1939 through 1943, none made by major studios, the most notable being Guadalcanal Diary (1943).

Stander was blacklisted from the late 1940s until 1965; perhaps the longest period.

In 1941, he starred in a short-lived radio show called The Life of Riley on CBS, no relation to the radio, film, and television character later made famous by william Bendix. Stander played the role of Spider Schultz in both Harold Lloyd's film The Milky Way (1936) and its remake ten years later, The Kid from Brooklyn (1946), starring Danny Kaye. He was a regular on Danny Kaye's zany comedy-variety radio show on CBS (1946–1947), playing himself as "just the elevator operator" amidst the antics of Kaye, Future Our Miss Brooks star Eve Arden, and bandleader Harry James.

Stander appeared in no films between 1944 and 1945. Then, with HUAC's attentions focused elsewhere due to World War II, he played in a number of mostly second-rate pictures from independent studios through the late 1940s. These include Ben Hecht's Specter of the Rose (1946); the Preston Sturges comedy The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (1947) with Harold Lloyd; and Trouble Makers (1948) with The Bowery Boys. One classic emerged from this period of his career, the Preston Sturges comedy Unfaithfully Yours (1948) with Rex Harrison.

In 1947, HUAC turned its attention once again to Hollywood. That October, Howard Rushmore, who had belonged to the CPUSA in the 1930s and written film reviews for the Daily Worker, testified that Writer John Howard Lawson, whom he named as a Communist, had "referred to Lionel Stander as a perfect Example of how a Communist should not act in Hollywood." Stander was again blacklisted from films, though he played on TV, radio, and in the theater.

At a HUAC hearing in April 1951, actor Marc Lawrence named Stander as a member of his Hollywood Communist "cell", along with Screenwriter Lester Cole and Screenwriter Gordon Kahn. Lawrence testified that Stander "was the guy who introduced me to the party line", and that Stander said that by joining the CP, he'd "get to know the dames more"—which Lawrence, who didn't enjoy film-star looks, thought a good idea. Upon hearing of this, Stander shot off a telegram to HUAC chair John S. Wood, calling Lawrence's testimony that he was a Communist "ridiculous" and asking to appear before the Committee, so he could swear to that under oath. The telegram concluded: "I respectfully request an opportunity to appear before you at your earliest possible convenience. Be assured of my cooperation." Two days later, Stander sued Lawrence for $500,000 for slander. Lawrence left the country ("fled", according to Stander) for Europe.

After that, Stander was blacklisted from TV and radio. He continued to act in the theater roles, and played Ludlow Lowell in the 1952-53 revival of Pal Joey on Broadway and on tour.

Other notable statements during Stander's 1953 HUAC testimony:

Life improved for Stander when he moved to London in 1964 to act in Bertolt Brecht's Saint Joan of the Stockyards, directed by Tony Richardson, for whom he'd acted on Broadway, along with Christopher Plummer, in a stillborn 1963 production of Brecht's The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui. In 1965, he was featured in the film Promise Her Anything. That same year Richardson cast him in the black comedy about the funeral industry, The Loved One, based on the novel by Evelyn Waugh, with an all-star cast including Jonathan Winters, Robert Morse, Liberace, Rod Steiger, Paul Williams and many others. In 1966, Roman Polanski cast Stander in his only starring role, as the thug Dickie in Cul-de-sac, opposite Françoise Dorléac and Donald Pleasence.

Stander stayed in Europe and eventually settled in Rome, where he appeared in many spaghetti Westerns, most notably playing a bartender named Max in Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West. In Rome he connected with Robert Wagner, who cast him in an episode of It Takes a Thief that was shot there. Stander's few English-language films in the 1970s include The Gang That Couldn't Shoot Straight with Robert De Niro and Jerry Orbach, Steven Spielberg's 1941, and Martin Scorsese's New York, New York, which also starred De Niro and Liza Minnelli.

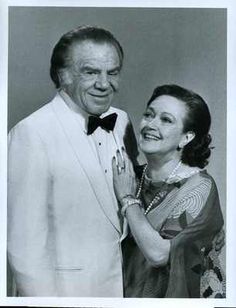

After 15 years abroad, Stander moved back to the U.S. for the role he is now most famous for: Max, the loyal butler, cook, and chauffeur to the wealthy, amateur detectives played by Robert Wagner and Stefanie Powers on the 1979–1984 television series Hart to Hart (and a subsequent series of Hart to Hart made-for-television films). In 1983, Stander won a Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor – Series, Miniseries or Television Film.

In 1986, he became the voice of Kup in The Transformers: The Movie. In 1991 he was a guest star in the television series Dream On, playing Uncle Pat in the episode "Toby or Not Toby". His final theatrical film role was as a dying hospital patient in The Last Good Time (1994), with Armin Mueller-Stahl and Olivia d'Abo, directed by Bob Balaban.

Stander died of lung cancer in Los Angeles, California, in 1994 at age 86. He was buried in Glendale's Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery.

After that, Stander's acting career went into a free fall. He worked as a stockbroker on Wall Street, a journeyman stage actor, a corporate spokesman—even a New Orleans Mardi Gras king. He didn't return to Broadway until 1961 (and then only briefly in a flop) and to film in 1963, in the low-budget The Moving Finger (although he did provide, uncredited, the voice-over narration for the 1961 noir thriller Blast of Silence.)