Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Physicist |

| Birth Day | November 07, 1878 |

| Birth Place | Vienna, Austrian |

| Age | 141 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 27 October 1968(1968-10-27) (aged 89)\nCambridge, England |

| Birth Sign | Sagittarius |

| Residence | Austria, Germany, Sweden, United Kingdom |

| Citizenship | Austria (pre-1949), Sweden (post-1949) |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Known for | Nuclear fission |

| Awards | Lieben Prize (1925) Max Planck Medal (1949) Otto Hahn Prize (1955) ForMemRS (1955) Wilhelm Exner Medal (1960) Enrico Fermi Award (1966) |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | Kaiser Wilhelm Institute University of Berlin, Manne Siegbahn Laboratory (sv) University College of Stockholm |

| Doctoral advisor | Franz S. Exner |

| Other academic advisors | Ludwig Boltzmann Max Planck |

| Doctoral students | Arnold Flammersfeld Kan-Chang Wang Nikolaus Riehl |

| Other notable students | Max Delbrück Hans Hellmann |

| Influenced | Otto Hahn |

Net worth

Lise Meitner, an accomplished physicist from Austria, is projected to have an estimated net worth of $100K - $1M in 2024. Renowned for her significant contributions to the field of nuclear physics, Meitner's incredible intellect and groundbreaking research have solidified her place in scientific history. Despite facing numerous challenges as a woman in the predominantly male-dominated field, her pioneering work in understanding the process of nuclear fission has shaped the foundations of modern physics. Meitner's legacy serves as an inspiration to aspiring scientists worldwide, and her estimated net worth reflects the immeasurable value of her intellectual contributions.

Famous Quotes:

The discovery of nuclear fission by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann opened up a new era in human history. It seems to me that what makes the science behind this discovery so remarkable is that it was achieved by purely chemical means.

Biography/Timeline

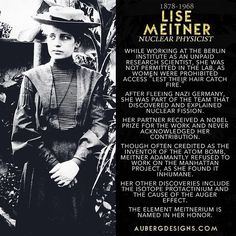

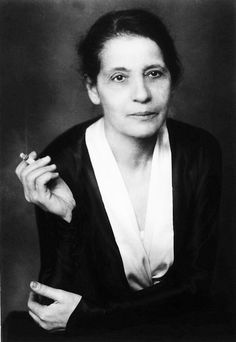

She was born Elise Meitner on 7 November 1878 into a Jewish upper-middle-class family in Vienna, 2nd district (Leopoldstadt), the third of eight children. Her father Philipp Meitner was one of the first Jewish lawyers in Austria. She shortened her name from Elise to Lise. The birth register of Vienna's Jewish community lists Meitner as being born on 17 November 1878, but all other documents list her date of birth as 7 November, which is what she used. As an adult, she converted to Christianity, following Lutheranism, and was baptized in 1908.

Meitner's earliest research began at age 8, when she kept a notebook of her records underneath her pillow. She was particularly drawn to math and science, and first studied colors of an oil slick, thin films, and reflected light. Women were not allowed to attend public institutions of higher education in Vienna around 1900, but Meitner was able to achieve a private education in physics in part because of her supportive parents, and she completed in 1901 with an "externe Matura" examination at the Akademisches Gymnasium.

Meitner studied physics and went on to become the second woman to obtain a doctoral degree in physics at the University of Vienna in 1905 (her dissertation was on "heat conduction in an inhomogeneous body"). While at the University, she took her studies very seriously. Because she was unsure if she wanted to study mathematics or physics, she attended multiple lectures in both areas of study, "taking more notes than the registered students".

While studying a beam of alpha particles, she found that scattering increased with the atomic mass of the metal atoms, in her experiments with collimators and metal foil, which led Ernest Rutherford later on to the nuclear atom, and which had been her forte, submitting her report of same to the Physikalische Zeitschrift on 29 June 1907.

After one year of attending Planck's lectures, Meitner became Planck's assistant. During the first years she worked together with Chemist Otto Hahn and together with him discovered several new isotopes. In 1909 she presented two papers on beta-radiation. She also, together with Otto Hahn, discovered and developed a physical separation method known as radioactive recoil, in which a daughter nucleus is forcefully ejected from its matrix as it recoils at the moment of decay.

In 1912 the research group Hahn–Meitner moved to the newly founded Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institute (KWI) in Berlin-Dahlem, south west in Berlin. She worked without salary as a "guest" in Hahn's department of Radiochemistry. It was not until 1913, at 35 years old and following an offer to go to Prague as associate professor, that she got a permanent position at KWI.

In the first part of World War I, she served as a nurse handling X-ray equipment. She returned to Berlin and her research in 1916, but not without inner struggle. She felt in a way ashamed of wanting to continue her research efforts when thinking about the pain and suffering of the victims of war and their medical and emotional needs.

In 1917, she and Hahn discovered the first long-lived isotope of the element protactinium, for which she was awarded the Leibniz Medal by the Berlin Academy of Sciences. That year, Meitner was given her own physics section at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry.

In 1926, Meitner became the first woman in Germany to assume a post of full professor in physics, at the University of Berlin. In 1935, as head of the physics department of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Berlin-Dahlem (today the Hahn-Meitner Building of the Free University) she and Otto Hahn, the Director of the KWI, undertook the so-called "transuranium research" program. This program eventually led to the unexpected discovery of nuclear fission of heavy nuclei in December 1938, half a year after she had left Berlin. She was praised by Albert Einstein as the "German Marie Curie".

In 1930, Meitner taught a seminar on nuclear physics and chemistry with Leó Szilárd. After the discovery of the neutron in the early 1930s, the scientific community speculated that it might be possible to create elements heavier than uranium (atomic number 92) in the laboratory. A scientific race began between the teams of Ernest Rutherford in Britain, Irène Joliot-Curie in France, Enrico Fermi in Italy, and Meitner and Hahn in Berlin. At the time, all concerned believed that this was abstract research for the probable honour of a Nobel prize. None suspected that this research would culminate in nuclear weapons.

After the war, Meitner, while acknowledging her own moral failing in staying in Germany from 1933 to 1938, was bitterly critical of Hahn, Max von Laue and other German Scientists who, she thought, would have collaborated with the Nazis and done nothing to protest against the crimes of Hitler's regime. Referring to the leading German nuclear Physicist Werner Heisenberg, she said: "Heisenberg and many millions with him should be forced to see these camps and the martyred people." In a June 1945 draft letter addressed to Hahn, but never received by him, she wrote:

Hahn and Strassmann had sent the manuscript of their first paper to Naturwissenschaften in December 1938, reporting they had detected and identified the element barium after bombarding uranium with neutrons; simultaneously, Hahn had communicated their results exclusively to Meitner in several letters, and did not inform the physicists in his own institute.

These three reports, the first Hahn-Strassmann publication of January 6, 1939, the second Hahn-Strassmann publication of February 10, 1939, and the Frisch-Meitner publication of February 11, 1939, had electrifying effects on the scientific community. Because there was a possibility that fission could be used as a weapon, and since the knowledge was in German hands, Szilárd, Edward Teller, and Eugene Wigner jumped into action, persuading Albert Einstein, a Celebrity, to write President Franklin D. Roosevelt a letter of caution. In 1940 Frisch and Rudolf Peierls produced the Frisch–Peierls memorandum, which first set out how an atomic explosion could be generated, and this ultimately led to the establishment in 1942 of the Manhattan Project. Meitner refused an offer to work on the project at Los Alamos, declaring "I will have nothing to do with a bomb!" Meitner said that Hiroshima had come as a surprise to her, and that she was "sorry that the bomb had to be invented."

Meitner received many awards and honors late in her life, but she did not share in the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for nuclear fission that was awarded exclusively to her long-time collaborator Otto Hahn. In the 1990s, the records of the committee that decided on that prize were opened. Based on this information, several Scientists and journalists have called her exclusion "unjust", and Meitner has received a flurry of posthumous honors, including naming chemical element 109 meitnerium in 1992. Despite not having been awarded the Nobel Prize, Lise Meitner was invited to attend the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting in 1962.

Meitner was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1945, and had her status changed to that of a Swedish member in 1951. Four years later she was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1955. She was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1960.

On a visit to the USA in 1946, Meitner received the honour of "Woman of the Year" by the National Press Club and had dinner with President Harry Truman and others at the Women's National Press Club. She lectured at Princeton, Harvard and other US universities, and was awarded a number of honorary doctorates. She received jointly with Hahn the Max Planck Medal of the German Physical Society in 1949, and in 1955 she was awarded the first Otto Hahn Prize of the German Chemical Society. In 1957 the German President Theodor Heuss awarded her the highest German order for Scientists, the peace class of the Pour le Mérite. She was nominated by Otto Hahn for both honours. Meitner's name was submitted, also by Hahn, to the Nobel Prize committee more than ten times, but she was not accepted.

Meitner received 21 scientific honours and awards for her work (including 5 honorary doctorates and membership of 12 academies). In 1947 she received the Award of the City of Vienna for science. She was the first female member of the scientific class of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. In 1960, Meitner was awarded the Wilhelm Exner Medal and in 1967, the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art.

After the war in the 1950s and 1960s, Meitner again enjoyed visiting Germany and staying with Hahn and his family for several days on different occasions, particularly on March 8, 1959, to celebrate Hahn's 80th birthday in Göttingen, where she addressed recollections in his honour. Also Hahn wrote in his memoirs, which were published shortly after his death in 1968, that he and Meitner had remained lifelong close friends. Even though their friendship was full of trials, arguably more so experienced by Meitner, she "never voiced anything but deep affection for Hahn."

Max Perutz, the 1962 Nobel prizewinner in chemistry, reached a similar conclusion: "Having been locked up in the Nobel Committee's files these fifty years, the documents leading to this unjust award now reveal that the protracted deliberations by the Nobel jury were hampered by lack of appreciation both of the joint work that had preceded the discovery and of Meitner's written and Verbal contributions after her FLIGHT from Berlin."

A strenuous trip to the United States in 1964 led to Meitner having a heart attack, from which she spent several months recovering. Her physical and mental condition weakened by atherosclerosis, she was unable to travel to the US to receive the Enrico Fermi prize and relatives had to present it to her. After breaking her hip in a fall and suffering several small strokes in 1967, Meitner made a partial recovery, but eventually was weakened to the point where she moved into a Cambridge nursing home.

In 1966 Hahn, Fritz Strassmann and Meitner were jointly awarded the Enrico Fermi Award by President Lyndon B. Johnson and the United States Atomic Energy Commission (USAEC) in Washington D.C. Lise Meitner's diploma bears the words: "For pioneering research in the naturally occurring radioactivities and extensive experimental studies leading to the discovery of fission." Otto Hahn's diploma is different but essentially similar: "For pioneering research in the naturally occurring radioactivities and extensive experimental studies culminating in the discovery of fission."

Since Meitner's 1968 death, she has received many naming honours. In 1997, element 109 was named meitnerium in her honour. She is the first and so far only non-mythological woman thus honoured. (Curium was named after both Marie and Pierre Curie.) Additional naming honours are the Hahn–Meitner-Institut in Berlin, craters on the Moon and on Venus, and the main-belt asteroid 6999 Meitner.

In 2000, the European Physical Society established the biannual "Lise Meitner Prize" for excellent research in nuclear science. In 2006 the "Gothenburg Lise Meitner Award" was established by the University of Gothenburg in Sweden; it is awarded annually to a scientist who has made a breakthrough in physics. In 2008, the chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear defense school of the Austrian Armed Forces (NBC) established the Lise Meitner Award.

In October 2010, a building at the Free University of Berlin was named the Hahn-Meitner Building; this was a renaming of a building previously known as the Otto Hahn Building. In July 2014 a statue of Lise Meitner was unveiled in the garden of the Humboldt University of Berlin next to similar statues of Hermann von Helmholtz and Max Planck.

At the time Meitner herself wrote in a letter, "Surely Hahn fully deserved the Nobel Prize for chemistry. There is really no doubt about it. But I believe that Otto Robert Frisch and I contributed something not insignificant to the clarification of the process of uranium fission—how it originates and that it produces so much Energy and that was something very remote to Hahn." In a similar vein, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, Lise Meitner's former assistant, later added that Hahn "certainly did deserve this Nobel Prize. He would have deserved it even if he had not made this discovery. But everyone recognized that the splitting of the atomic nucleus merited a Nobel Prize." Frisch wrote similarly in a 1955 letter.

Since 2015 AlbaNova university centre in Stockholm has annual Lise Meitner Distinguished Lecture.

In 2017, the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy in the United States named a major nuclear Energy research program in her honor.